-

Fullerton in Deep Time

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

“The earth is over 4 billion years old, but the oldest rocks in the county are less than 200 million years old. Thus, the geologic history recorded in the rocks found in Orange County only covers about 5% of the entire earth history! But, an amazing variety of changes to the landscape has occurred in that relatively short span of geologic time. We shifted plate boundary types, evolved through changing climates and organisms, emerged from the sea, and witnessed mountains to grow over a mile high!”

–Richard Lozinsky, Our Backyard Geology in Orange County, California

The oldest rocks in Fullerton are in Coyote Hills. Not being a geologist, I rely upon the work of geologists to tell the story of Fullerton in time scales that are much larger and harder for humans to comprehend. We measure our lifetimes in decades. Geologists measure the Earth’s history in ages, eras, and epochs spanning millions of years.

Thankfully, I was guided on this journey by Fullerton College professor Richard Lozinsky, whose Earth Science class I took back around 2001. I found his class fascinating, as he used the rocks and landscapes of Orange County to teach us about geology concepts. We took field trips to places like Coyote Hills and Dana Point to learn about the stories rocks had to tell. A while back, I interviewed professor Lozinsky. You can read that HERE.

Recently, I re-read Lozinsky’s excellent book Our Backyard Geology in Orange County, California and so I present here a much simplified version of the local geologic story. For the sake of clarity (and my own comprehension), I am leaving out many technical terms and details.

About 200 million years ago, the supercontinent known as Pangea began breaking up into smaller plates. One of these new plates, the North American, began drifting westward.

About 29 million years ago, the North American Plate made contact with the Pacific Plate, and the two began a lateral (up-down movement) with the Pacific Plate moving upward. This created coastal depressions such as the Los Angeles Basin.

“Lands surrounding the basin began to emerge from the ocean forming a new coastline along the rising San Gabriel and Santa Ana Mountains. These new lands were relatively low lying and probably enjoyed a subtropical climate with rainfall amounts of 30-40 inches,” Lozinsky writes.

The marine life of the Los Angeles basin (like plankton) eventually died and formed the rich oil deposits that were discovered millions of years later.

“The ocean began its final retreat from the Orange County area about 5 million years ago when the convergence between the North American and Pacific plates intensified,” Lozinsky writes.

The San Andreas Fault Zone (SAFZ) formed at this time, and the Santa Ana river began to flow across the coastal zone, carrying sediment.

“By 1 million years ago,” Lozinsky writes, “the hills and mountains had almost reached their current elevations, defining the basin to look more like it does today. During the Pleistocene, the climate of the area was cooler and the landscape was grassland as indicated from the La Habra and Los Coyotes Formations. Here, sabre-tooth cat, giant ground sloth, dire wolf, horse, camel, bison, mammoth and mastodon roamed the region to eventually become extinct also.”

An excellent place to learn about this period is the Interpretive Center in Ralph B. Clark Regional Park, which contains fossils recovered locally of the above mentioned extinct creatures.

Ancient Mastodon molars on display at the Ralph B. Clark Park Interpretive Center. Over the next several thousand years, sea levels rose and fell as glaciers rose and melted.

“The present-day Orange County coastline was established about 10,000 years ago with the end of the Pleistocene. The earliest humans to visit our county probably came along the coast where food was more abundant,” Lozinsky writes.

Professor Lozinsky gives a glimpse into the future: “In the future, our coastline will slowly change as worldwide sea levels increase due to the melting of the polar ice caps and locally due to tectonic activity. Orange County will continue on its northwestward cruise towards Alaska as the Pacific Plate shifts with each earthquake that occurs along the SAFZ (San Andreas Fault Zone).”

-

Fullerton in 1945

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

President Roosevelt Died during his fourth term in office. In World War II, the Axis powers surrendered.

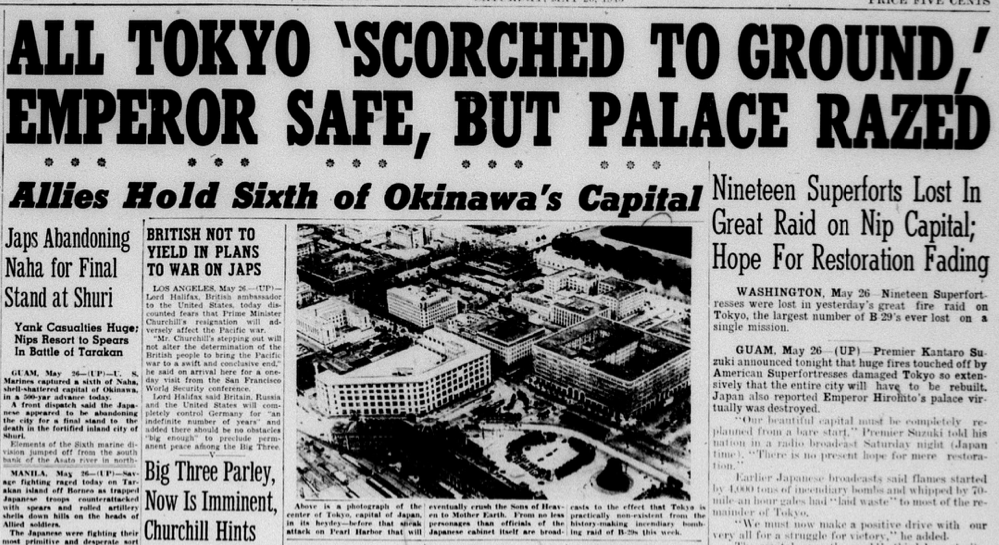

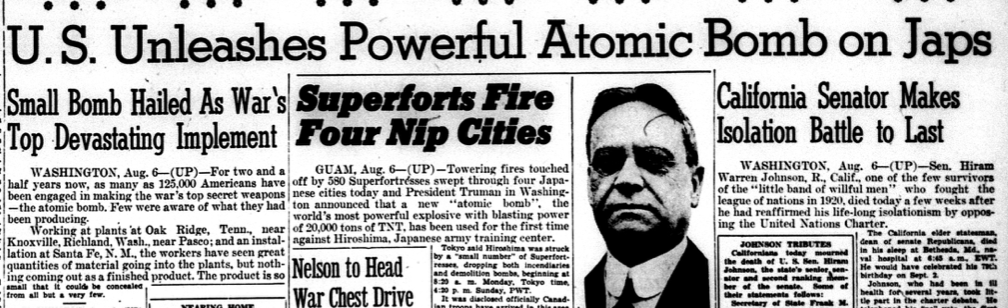

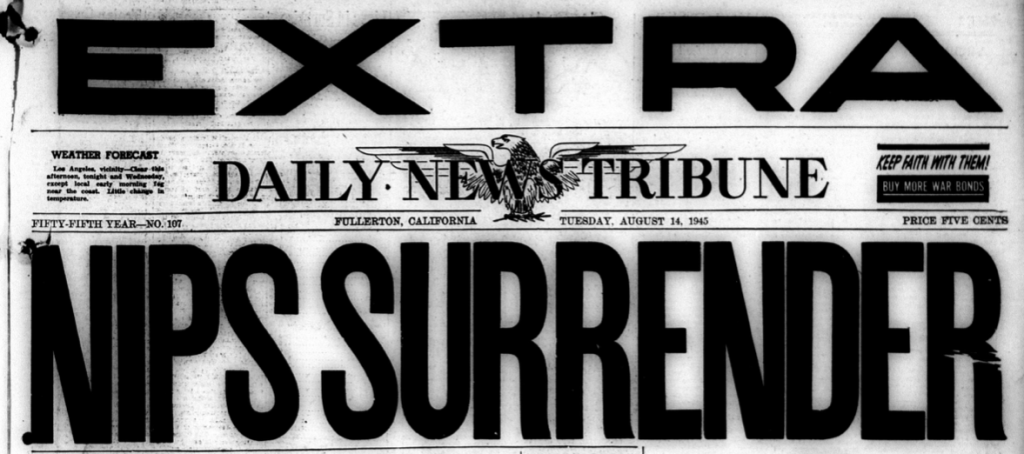

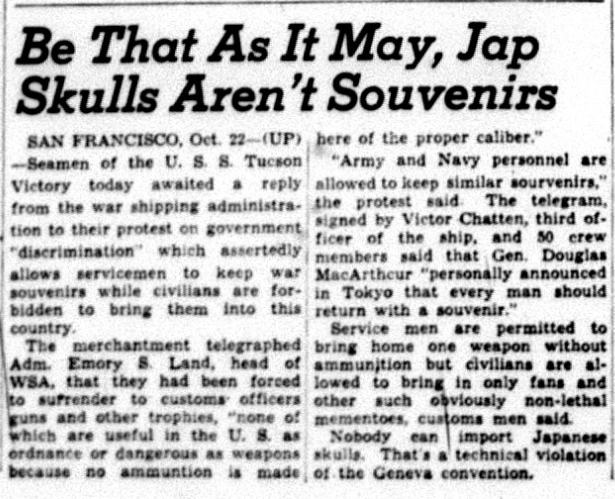

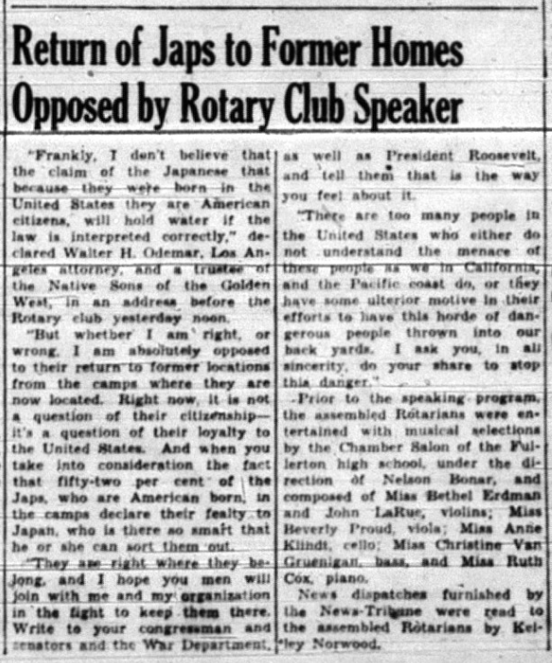

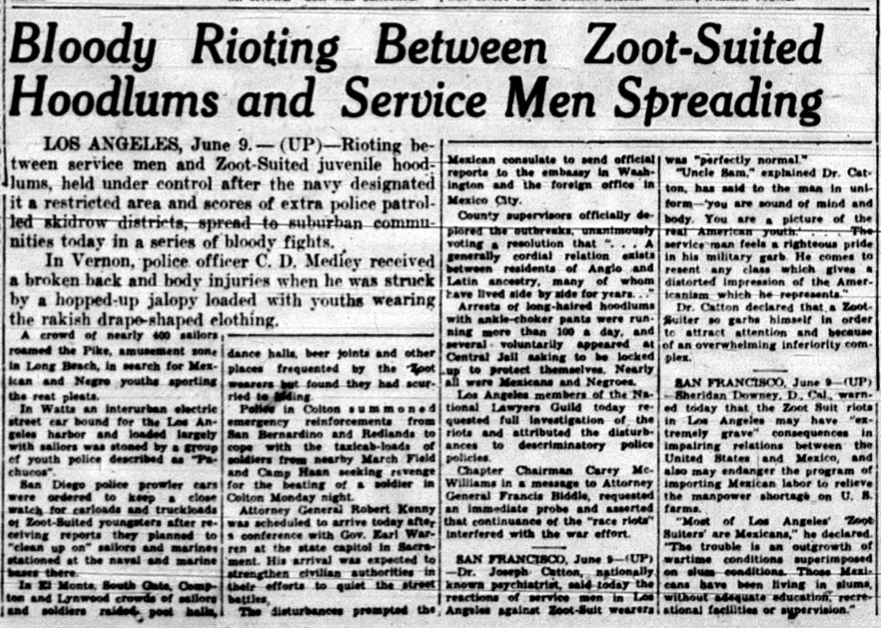

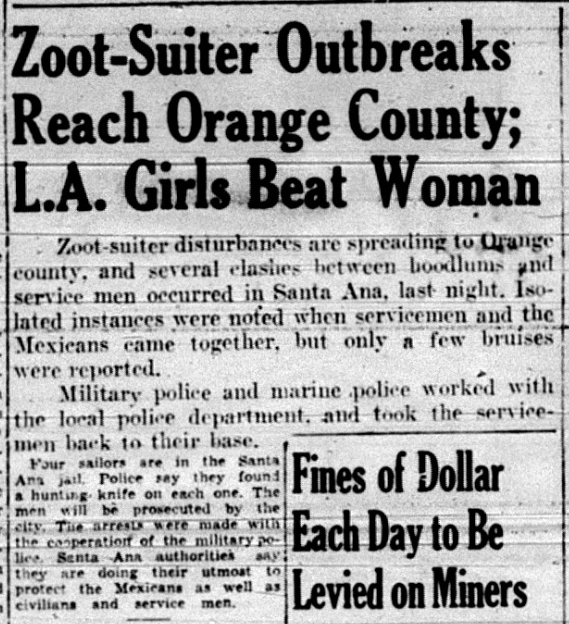

Following intense fire bombing of major cities and the dropping of two atomic bombs, Japan also surrendered. In keeping with the prejudice of the times, many headlines used the racist terms “Japs” and “Nips” to refer to the Japanese.

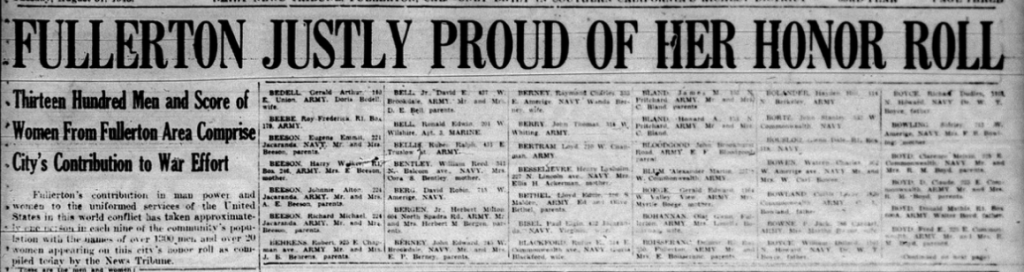

Fullertonians Killed in World War II

The News-Tribune ran an issue which included photos and a bit of information about some of the local boys killed in World War II. Here they are:

Post-War

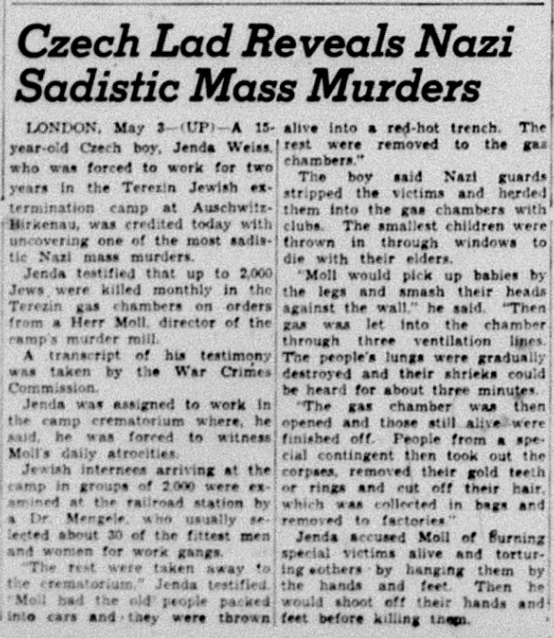

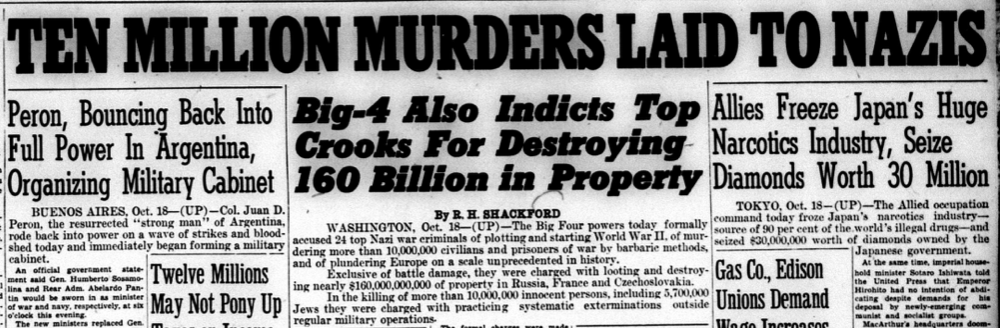

In the aftermath of World War II, a number of Nazi and Japanese military leaders were convicted of war crimes and executed.

As a result of these trials and other eyewitness testimony, the world learned of the full horror of the Holocaust.

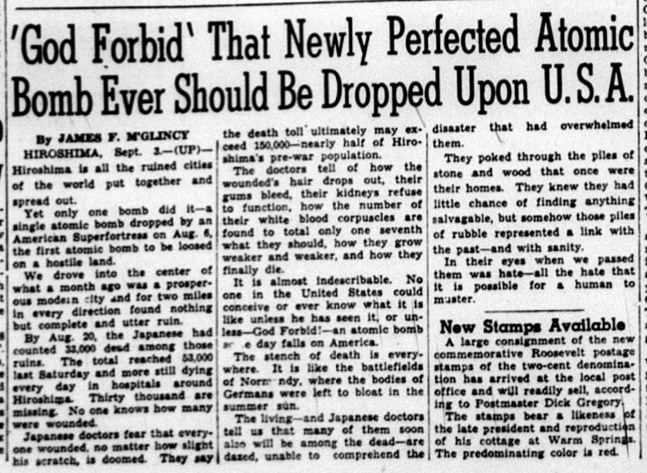

The full horror of the atomic fallout at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was also coming to light.

Because the United States was part of the winning side of the war, its leaders were not punished for mass murder. Instead, General Douglas MacArthur imposed a U.S.-led military government on Japan for six years, during which he clamped down on dissent and censored the media.

Meanwhile, as divisions grew with Russia and the first frosts of the Cold War were felt, President Harry Truman articulated what would become known as the Truman Doctrine:

“We shall refuse to recognize any government imposed upon any nation by the force of any foreign power,” Truman said. “In some cases it may be impossible to prevent forceful imposition of such a government. But the United States will not recognize any such government.”

Regimes forced by the United States on other nations (such as Japan) were, of course, not included in this doctrine.

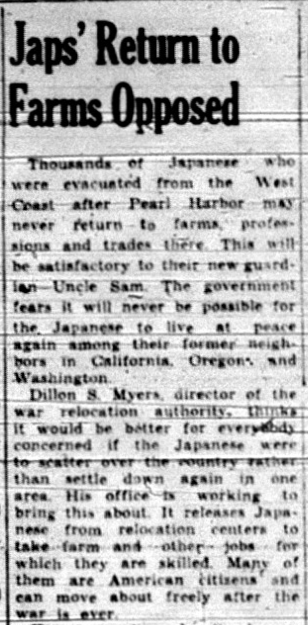

Racism against Japanese people persisted after the war, as shown by the following articles, in which mass sterilization of the Japanese is matter-of-factly proposed, and soldiers have to be told that taking Japanese skulls as souvenirs technically violates the Geneva convention.

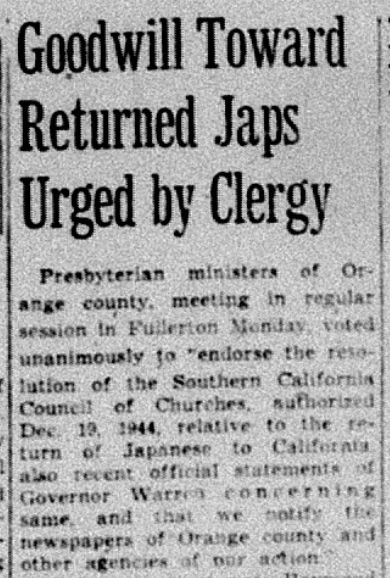

On the homefront, some clergy were urging Americans to extend goodwill to the over 100,000 Japanese Americans who were forced into internment camps during the war when they returned home.

Perhaps the thorniest post-war question was what to do now that the atomic bomb existed–a weapon that could theoretically destroy the world.

On a more positive note, congress passed the GI Bill in 1944, which provided veterans with financial aid for housing, education, and more.

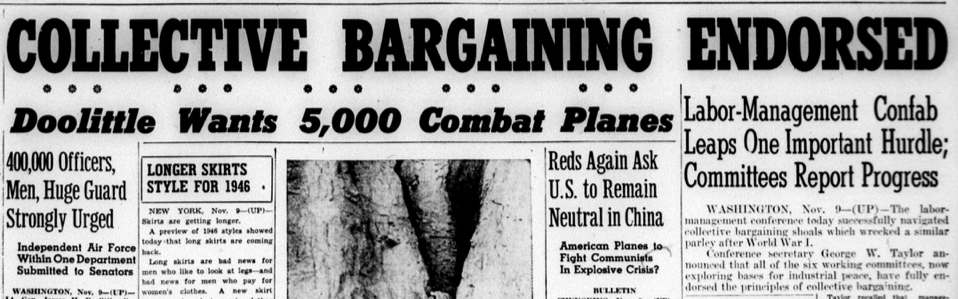

The Labor Strikes of 1945-46

Amid all the jubilation and relief following the end of World War II, some of the largest labor strikes in American history swept major industries like cars, oil, motion pictures, coal, steel, canning, and more. Hundreds of thousands of workers struck–with many of them gaining the kind of strong union powers (like collective bargaining for better wages, benefits, and working conditions) that helped build America’s post-war blue collar middle class.

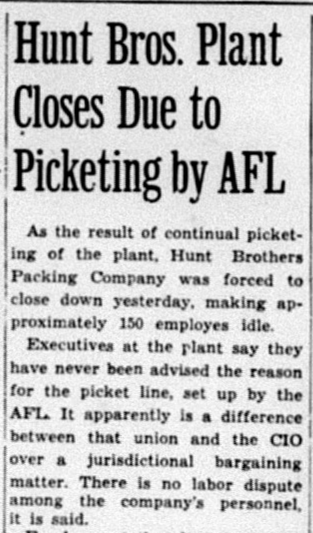

The strikes even came to Fullerton, with picketers closing down the Hunt Bros. Canning factory.

Citrus Industry

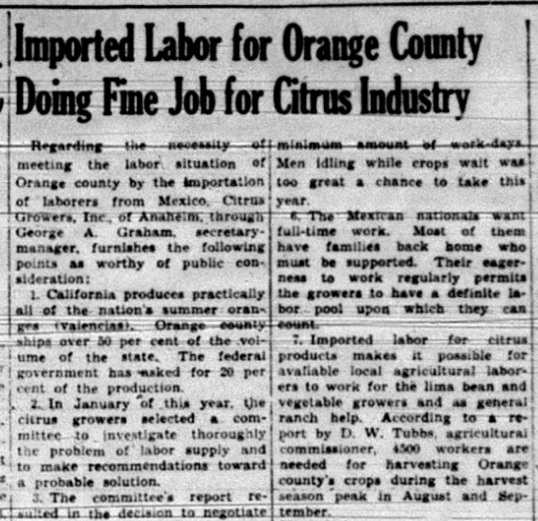

The local citrus industry had always relied on foreign labor. During World War II, Nazi war prisoners were taken to camps (including one in Garden Grove) and “hired” out to lower growers.

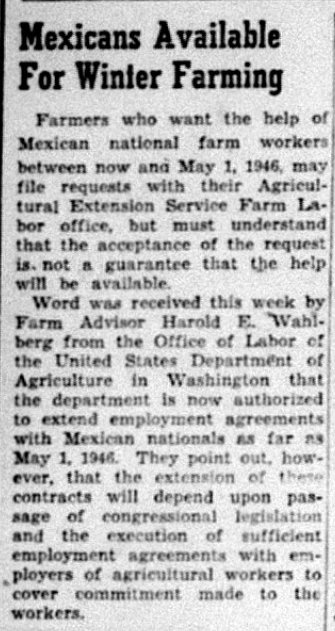

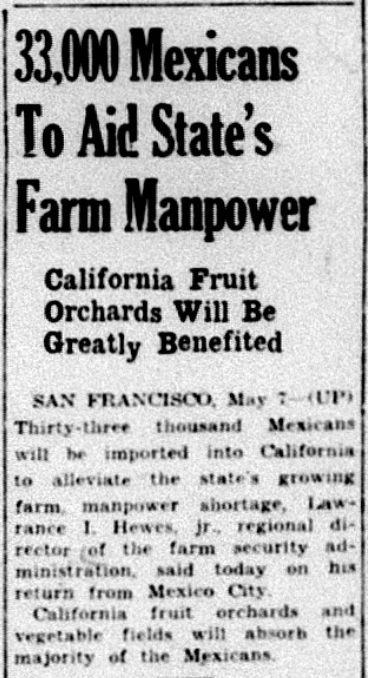

To help address labor shortages during the war, the Bracero program was created, which was sort of a guest worker program for Mexicans. This program would continue for two decades after the war, until 1964.

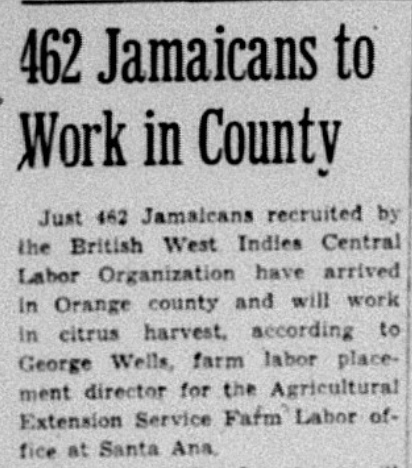

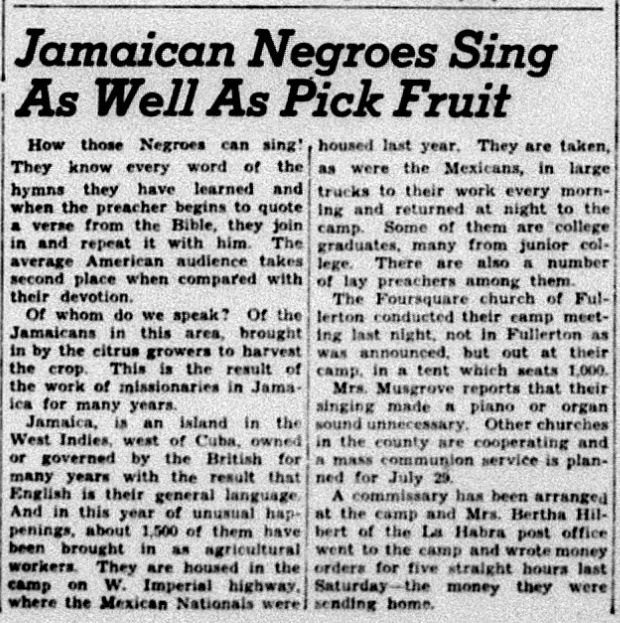

Additionally, hundreds of Jamaican workers were imported to a camp north of Fullerton, near La Habra.

In one disturbing incident, a worker was killed in a conflict that was initially described as a lynching. Fullerton (and Orange County generally) has historically been pretty hostile to Black people.

Culture and Entertainment

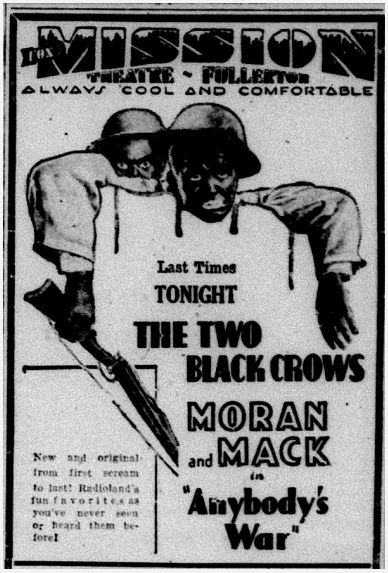

For culture and entertainment, locals went to see movies at the Fox Theater.

The Fullerton Police Department hosted an annual vaudeville show.

Education

In education news, Stanley Warburton was made the new superintendent of the Fullerton Union High School and Junior College.

The district would eventually purchase a plot of land on which special low-cost housing for veterans and their families was built.

In 1945, segregation of Mexican students from their white peers was being challenged in Orange County in a case that would eventually become Mendez et al v. Westminster.

Deaths

Long time teacher Anita Shepardson died.

Anna H. Sherwood also died.

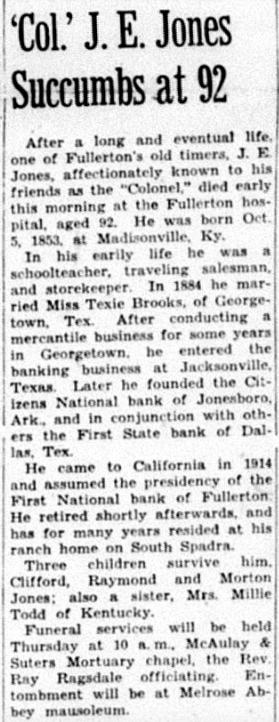

Colonel J.E. Jones died.

Stay tuned for top news stories from 1946!

-

A Brief History of Immigration to Fullerton

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Lately, given the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrants, I’ve been thinking a lot about the history of immigration, specifically to my hometown of Fullerton, California. I think that if more people knew about the history of immigration, they might favor a more nuanced and compassionate approach.

And so I thought I’d sit down and try to write a brief history of immigration to Fullerton. Next week, I plan on interviewing professor Jody Agius Vallejo, who teaches about immigration at USC, for my podcast. Perhaps this brief history can serve as a starting point for our conversation. Here goes.

Of course the indigenous people were here first–the Kizh. They were here for thousands of years.

Then in the 1700s came the Spanish. They didn’t exactly immigrate. They came to colonize–establishing missions and forts and towns. Los Angeles was founded in 1781, for example. The Spanish did not treat the Kizh well–disease, violence, and displacement led to an alarming population collapse.

Then in 1821, Mexico gained its independence from Spain. What we call Fullerton became part of a Mexican ranch owned by Juan Pacifico and Maria Ontiveros.

Juan Pacifico and Maria Ontiveros. In the early to mid 1800s, some Americans came to Mexican California. They could be called immigrants. An American named Abel Stearns came as a trader in cow hides, married a Mexican woman, and eventually acquired a lot of land, including the Ontiveros ranch.

In the mid-1840s, some Americans, including Captain John C. Fremont, came to Mexican California and tried (unsuccessfully) to foment a rebellion–this was called the Bear Flag revolt. They were asked to leave by the Mexican authorities. These Americans might be called the first “illegal” immigrants to California.

From 1846-1848, the United States went to war with Mexico because it wanted more land. This was called Manifest Destiny. Battles were fought, and the Americans won the war. California became a US state in 1850. The previous year, 1849, was the height of the California gold rush, which brought many American settlers and foreign immigrants, seeking their fortunes.

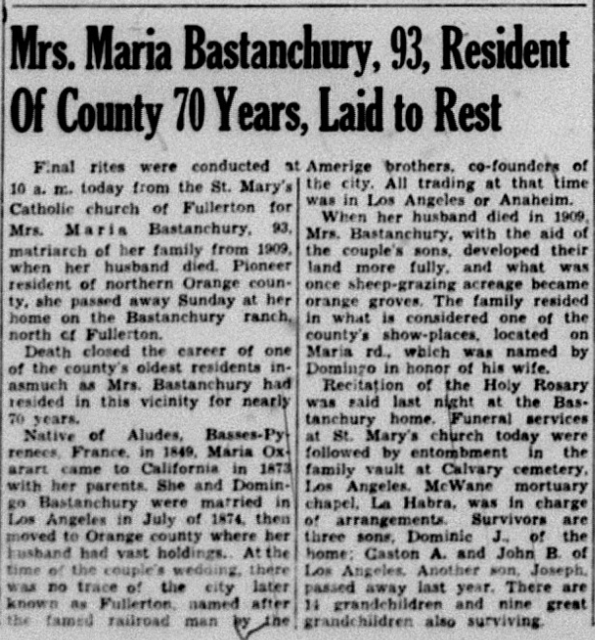

Around 1860, a Basque immigrant named Domingo Bastanchury came to the land that would become Fullerton and acquired a lot of land for his sheep to graze.

In the 1870s, a handful of immigrants came by wagon train to lands that would become Fullerton to establish farms. These included people like Alex Gardiner (an immigrant from Scotland) and Andrew Rorden (an immigrant from Germany).

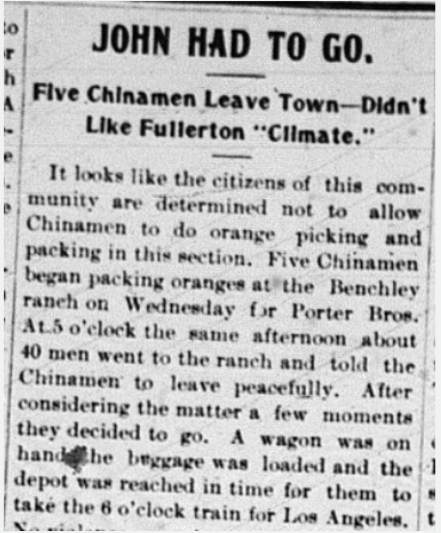

In the late 1860s, many Chinese immigrated to California to help build the Transcontinental Railroad. With the railroad completed, the Chinese settled in California cities. They were met with virulent racism and violence. Ultimately, the US government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, essentially barring immigrants from China.

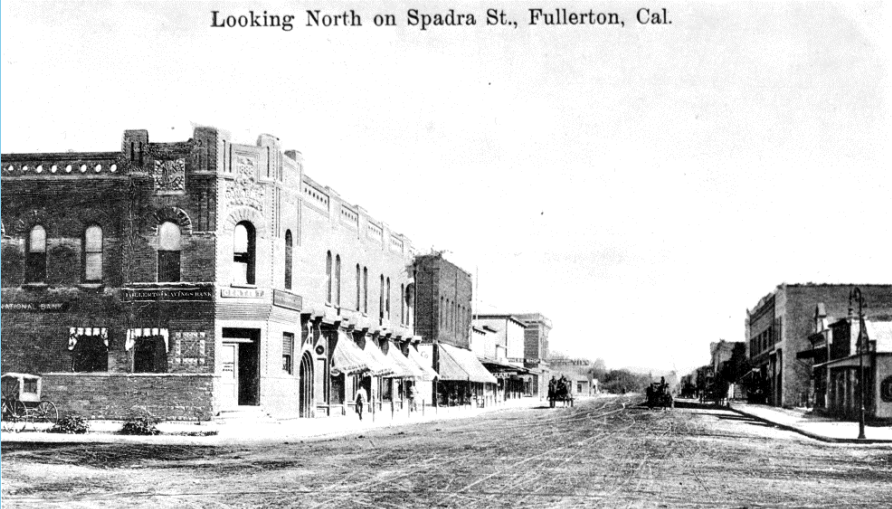

Fullerton was founded in 1887 by George and Edward Amerige, two wealthy grain merchants from Boston. More Americans came out west around this time, mostly on trains.

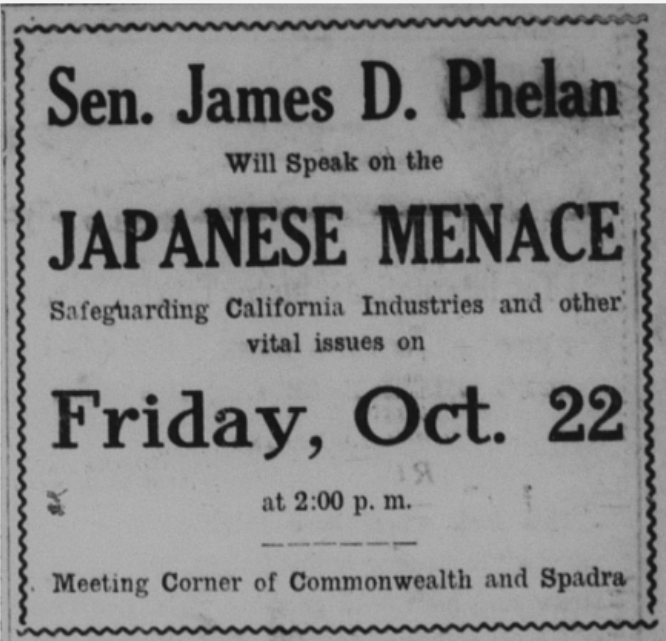

With the Chinese excluded, many Japanese immigrated to California to work in the growing agriculture industry. Unfortunately, the same pattern of racism and exclusion was inflicted on Japanese immigrants, who were eventually barred from owning land by the Alien Land Laws.

From 1911-1921, the violence of the Mexican Revolution and agricultural labor needs in California prompted many Mexicans to immigrate north to California, to the land that used to be part of their country. It was the labor of Mexican immigrants that made the Orange County citrus industry grow and thrive. Unfortunately, Mexicans in the first half of the 20th century were met by racism and exclusion, often living in segregated labor camps.

In the 1920s, a growing wave of “nativism” (a desire to protect the interests of native-born or established inhabitants against those of immigrants) led to the passage of the 1924 Immigration Act, which created national origins quotas that favored northern and western European immigrants, and barred most immigrants from Asia, and severely curtailed immigration from southern and eastern Europe. The 1924 law created the U.S. Border Patrol. Interestingly, the 1924 law did not impose quotas on western hemisphere countries. Immigrants from Mexico and Latin America could cross the border with relative ease, although they might encounter racism and exclusion once they arrived here.

During the Great Depression, many Mexicans living in the Fullerton area were subject to a mass deportation. Nine trainloads of Mexicans (including some American citizens) living on the Bastanchury Ranch were deported. The Bastanchury family was not to blame–they had already lost most of their ranch due to bankruptcy.

During World War II, with labor shortages in agriculture and industry, the U.S. government created the Bracero Program, which was basically a guest worker program for Mexicans to come to the US to work.

In 1952, congress passed the McCarran-Walter Act, which continued the national origins quotas, but eliminated the Asiatic Barred Zone (although the quotas for Asian countries were miniscule compared to countries like England and Germany).

In 1954, the U.S. government implemented Operation Wetback, another mass deportation drive targeting Mexican immigrants. Many were deported. A pattern emerged–Mexican immigrants, being the most conspicuous presence in Fullerton, were often the targets of mass deportation operations.

In 1964, the Bracero program ended, and the following year congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which abolished the (arguably racist) national origins quotas, but for the first time placed a numerical limit on the number of immigrants from the entire Western Hemisphere (120,000 per year). Although this law was celebrated as a civil rights victory, its cap on immigrants from Latin America created the conditions for illegal immigration as labor needs had not changed in the United States.

Predictably, illegal immigration from Mexico and elsewhere in Latin America increased dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s. This was exacerbated by the numerous covert wars in Latin America that the United States sponsored during this time in the context of the Cold War.

The Vietnam War and its aftermath created a large influx of Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees and immigrants to Orange County, with many settling in what is now called Little Saigon.

The 1960s through the early 1980s also saw a large influx of immigrants from South Korea to California, to such places as Koreatown in Los Angeles. After the 1992 LA Riots, many Koreans moved out of LA, to places like Fullerton, drawn by educational opportunities, jobs, and safe neighborhoods.

During the Reagan administration, congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, which provided Amnesty (a pathway to citizenship) for around 3 million undocumented immigrants. At the same time, this law also increased the Border Patrol and INS enforcement.

Congress passed the the Immigration Act of 1990 which increased immigration levels and introduced new visa categories, prioritizing family-based and employment-based immigration. It also introduced the Diversity Visa lottery to increase immigration from underrepresented countries.

Meanwhile, the Republican party became increasingly associated with hardline immigration restriction, as pioneered by groups like the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), the Center for Immigration Studies, and Americans for Legal Immigration (ALIPAC).

In 1994, another wave of nativism (particularly in California) led to the passage of Proposition 187, which sought to deny all government benefits to undocumented immigrants, including public education. Prop 187 backfired, though. It was ultimately deemed unconstitutional, and also inspired a generation of Latino civil rights activists, including Alex Padilla, who is now a California Senator.

1994 was also the year of Operation Gatekeeper, a beefing up of border security around San Diego, which had the effect (as all such measures do) of re-routing migrants into more dangerous terrain, where more died needlessly.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) was created in 2003 as part of the newly-formed Department of Homeland Security, in the aftermath of 9/11.

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program was established during the Obama Administration after the DREAM Act failed to pass Congress, but the Obama Administration also deported millions of undocumented immigrants.

Donald Trump’s first administration was notable for its hardline on undocumented immigrants, and it was Trump who established a ban on travel from majority Muslim countries, child separations, and more deportations.

The Biden administration sought to streamline the asylum process with the creation of the CBP One app, but illegal crossings surged under Biden. He sought to pass a bipartisan immigration reform bill, but it too died.

And in Trump’s second term, he has ramped up ICE raids and created an environment of fear, particularly for Latinos.

Today, Fullerton’s demographics are 37% Hispanic, 29% White, 26% Asian, and 2% Black.

I know there is more to this story, a lot more. I am still learning, particularly about more recent immigration laws and policies. Hopefully, my conversation with Jody Vallejo will help fill in some of the gaps.

-

Fullerton in 1944

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library has microfilm from the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune newspaper stretching back to 1893. I am in the process of reading over the microfilm, year by year, to get a sense of what was happening in the town over the years, and creating a mini archive. Below are some news stories from 1944.

World War II

World War II still raged across the world.

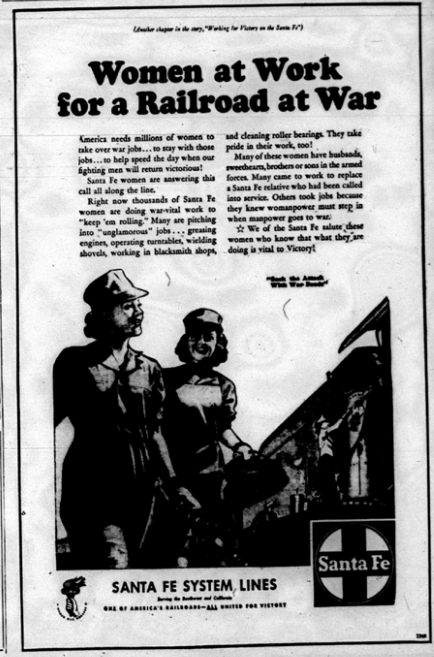

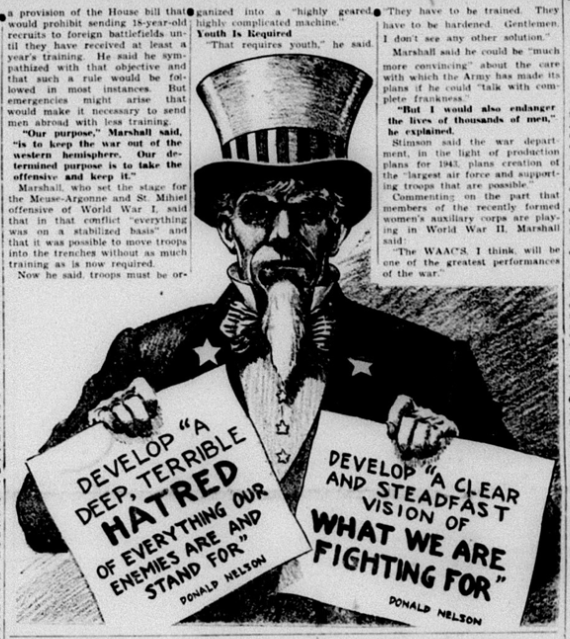

The War at Home

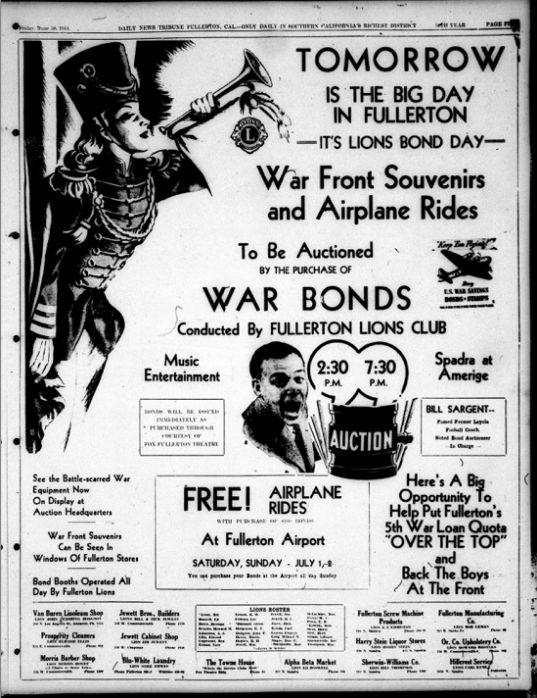

On the homefront, Fullertonians did their part to support the war effort, including buying war bonds and patriotic events.

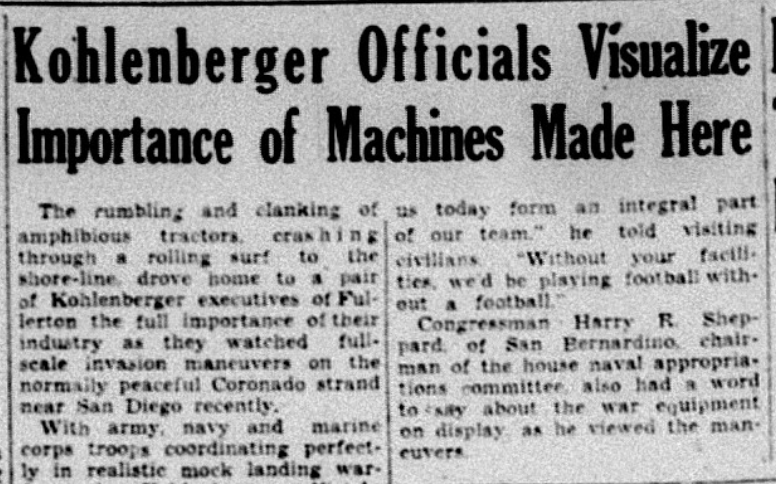

Local industries, like Kohlenberger Engineering and Hunt Foods produced products for the war. Kohlenberger built transimission systems for Amphibious Landing Craft, like the kind used in the invasion of Normandy on D-day.

Politics

Voters elected Verne Wilkinson, William Montague, and Hans Kohlenberger to City Council.

Montague, an orange rancher, was selected as Mayor.

Despite some pushback, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected to an unprecedented fourth term.

Sports

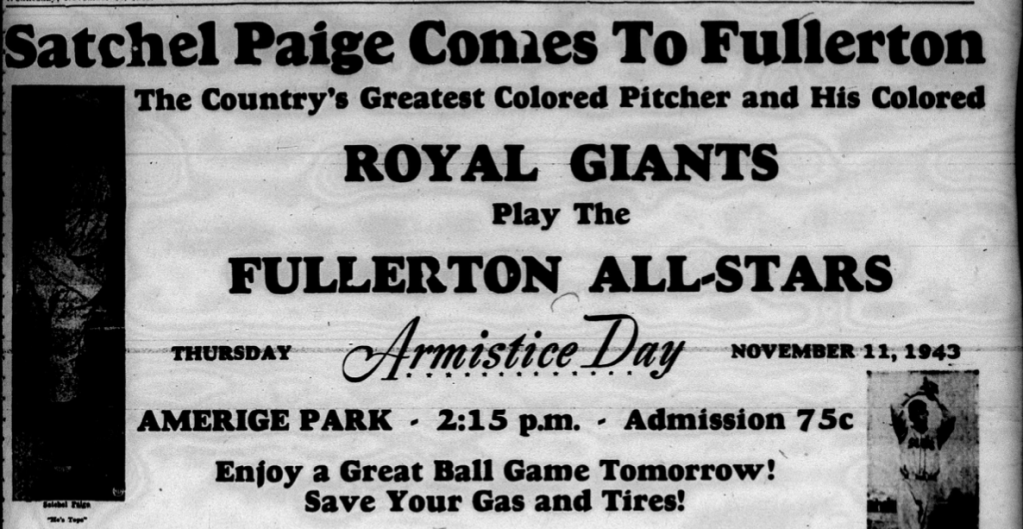

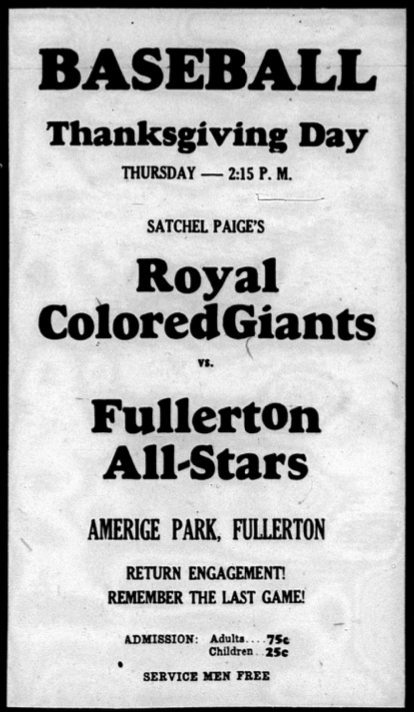

Baseball remained a popular local attraction, with local teams playing games at Amerige Park.

The Fullerton Union High School pool, or Plunge, opened to the public in the summer months.

Education

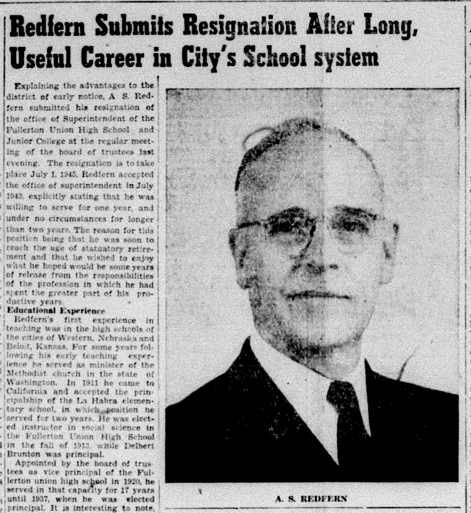

School administrator Redfern submitted his resignation.

Misecllaneous

Below are a some interesting miscellaneous articles from 1944:

Deaths

Pioneer orange rancher and Fullerton’s first mayor Charles C. Chapman died.

Here is his obituary:

Charles Clarke Chapman, pioneer of Fullerton, a civic leader here for many years and one of the most prominent business men and philanthropists in the southland, passed away at his home on North Cypress last evening at 10:30 o’clock. He would have been 91 years of age next July.

Known as the “father of the valencia orange industry,” Mr. Chapman had other manifold interests and was engaged in many philanthropic and educational enterprises.

Funeral services will be held at the Christian church next Monday at 2pm McAulay and Suters will be in charge.

Chapman was born July 2, 1853 in Macomb, Illinois. As a Western Union messenger boy he carried the message of President Lincoln’s assassination. In 1871 he went to Chicago and after some years in the building trades, in 1878 began the publication of local county histories, being a pioneer in this method of preserving local history and biography. He and his brother Frank built up an extensive publishing business and erected many buildings in Chicago.

In 1894 he came to California, residing first in Los Angeles at Adams and Figueroa, the present site of the Automobile Club of Southern California. In 1898 he moved to Fullerton, where he resided until his passing.

His first California real estate interest was a citrus orchard in Fullerton, where he developed the popularity of the Valencia orange and came to be known among old time citrus growers as the “father of the Valencia orange industry.” For thirty-two consecutive years his “Old Mission Brand” received the highest price for oranges in any market. He opened the first Valencia Orange Show in Orange County by personal telephone conversation with President Harding.

He was a frequent speaker at the Citrus Institute and did very much to further citrus production and packing methods. His citrus holdings in Fullerton have been increased to approximately 630 acres, now operated by family corporations.

Mr. Chapman was intimately identified with the development of Southern California.

In Los Angeles he was a large investor in real estate, owning many valuable properties, the outstanding of which is the Charles C. Chapman building at 8th and Broadway. He was president of the Fullerton Community Hotel Company and of the Fullerton Improvement Company and builder of the Charles C. Chapman building in Fullerton, where are maintained the offices of Placentia Orchard Company, of which he was president for fifty years. He served as director of the Farmers & Merchants bank of Fullerton, the Commercial National Bank of Los Angeles, the Bank of Italy of San Francisco and as chairman of the board of the original Bank of America of Los Angeles. He was a director of the Bank of America of Los Angeles.

He was a director of the Bank of America National Trust & Savings Ass’n. And served for many years as chairman of the board of the Fullerton branch. He was a director of the National Title Insurance Company of Los Angeles and for many years a member of the board of directors of the Christian board of Publication of St. Louis, Mo.

Deeply interested in the Masonic fraternity, he was a member of Fullerton Lodge No. 339 F & A.M; Fullerton Chapter No 90 R.A.M.; Santa Ana Council No. 14 R.&S.M. Fullerton Commandery…a 32nd degree member of the Los Angeles Scottish Rite and a member of Al Malaikah Shrine. He was a life member of the Los Angeles Athletic Club, the Chicago Historical Society, the New England Historical and Genealogical Society, a charter member of the Automobile Club of Southern California, a member of the Institute of American Genealogy, a Rotarian and a member of the Lincoln Club of Los Angeles from its inception.

Mr Chapman was active in the incorporation of the City of Fullerton and served as its first mayor. During the first World War he was chairman of the Selective Service Board of Northern Orange County. For ten years was a member of the State Immigration & Housing Commission and for ten years, a trustee of the San Diego State Teacher’s College. He was a lifelong Republican, active in party affairs in both State and Nation and served as a delegate to two National Republican Conventions, at one time being actively considered as nominee for vice president of the United States.

A devoted member of the Christian Church from early boyhood he continued his active support throughout his entire life. Although not an ordained minister he served as pastor of the church at Anaheim for the first years of his residence in this area and organized and served as the first pastor of the First Christian Church at Fullerton, being later chosen as Pastor Emeritus.

He has in his files over one thousand written sermons. For nineteen years he was President of the Christian Missionary Society of Southern California and presided over its annual conventions. He took active part in the dedication of one hundred and seven churches in Southern California. For many years a member of the State Executive Committee of the YMCA, he served for ten years as its chairman. He served as president of the State Sunday School Association and as vice president of the International Executive Committee. His purse always open for liberal contributions to worthy enterprises one of his undertakings was the building of a hospital at Nantung chow, China, which after years of great benefit to the teeming inhabitants of that area, was destroyed by Japanese bombs early in the Chinese War.

Formally schooled only in the elementary grades, Mr. Chapman educate himself by wide reading in many fields, was a gifted public speaker and a devoted supporter of higher education. For several years he served as a trustee of Pomona College. In 1920 he realized an ambition of many years by founding and endowing California Christian College, acting for twenty years as Chairman of the Board of Trustees. In his honor and because of the valued and continued support which he made to the institution, the Board of Trustees in 1933, changed the name to Chapman College. In June 1930, the University of Southern California conferred upon him the degree of Master of Arts–in recognition of distinguished services in the interests of education.

On October, 1884 at Austin, Texas, he married Miss Lizzie pearson, two children being born of this union, Ethel M., wife of Dr. William H. Wickett, and C. Stanley. Mrs. Chapman passed away in 1894.

In 1898 in Los Angeles, he married Miss Clara Irvin. One son was born of this union, Irvin Clarke.

Surviving, in addition to the widow and children are a sister, Mrs. Dolla E. Harris of Los Angeles, six grandchildren, Chas. M. and Wm. H, Jr, sons of Dr. and Mrs. Wickett. Elizabeth, Mary Anne and Stanley Jr., children of Mr. and Mrs. C. Stanley Chapman. Cheryl Ann, daughter or Mr. and Mrs. Irvin Chapman and two great-grandchildren, Penelope and Chas. Jr., children of Mrs. and Mrs. Chas. M. Widkett, all residing in Fullerton.

Additionally, the following folks died:

Stay tuned for top news stories from 1945!

-

Fullerton: 1921-1930

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Growth

Throughout the 1920s, Fullerton enjoyed a period of rapid growth, as shown by a 1922 population of over 10,000, 20 miles of paved roads, 15 new subdivisions on the market, hundreds of new homes being built, and 15 new business blocks going up. The 1921 shipments of oranges and lemons was 2645 carloads, walnuts was 120 cars, and the oil territory produced 30,000,000 barrels annually.

A 1921 article entitled “Building Boom On” states, “With five new business buildings under way in the downtown section, a new grammar school and scores of dwellings being erected in the outlying districts the activity in this direction has been most marked, and is entirely gratifying to all who are interested in the city’s progress…In addition to the above the new public work on sewers and lights have given employment to many men, and the water extension construction to begin in the near future, will swell the total to many more.”

In 1921, Fullerton business owners and residents began raising money for what would become the California Hotel (now called Villa del Sol), which would open in 1923. The Chapman Building was completed in 1923.

The California Hotel, built in 1923. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room.

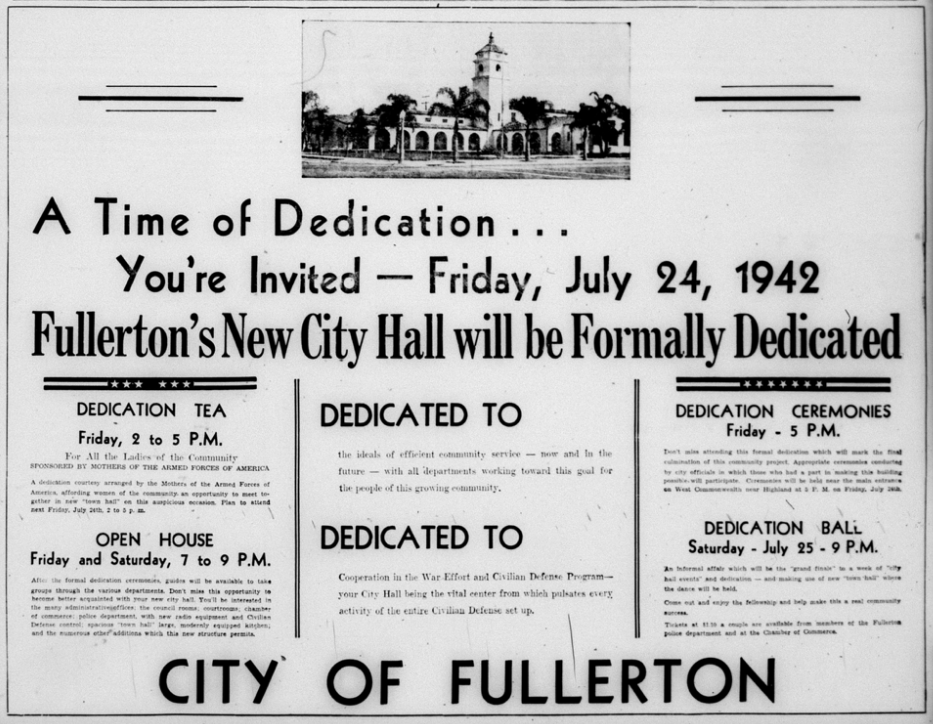

The Chapman Building, completed in 1923. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. There were plans in the works for constructing a City Hall; however, these were stalled and eventually scrapped. Fullerton City Hall (now the police station) would not be built for another 20 years. Meanwhile, the city government rented quarters in the Wickersheim building on West Commonwealth downtown.

Prior to the 1920s, Fullerton’s two main industries were oranges and oil. Starting in the 20s, the city created a 400-acre industrial zone where factories could locate.

These early factories included: Western Glass Company, Balboa Motor Corporation, Newton Process Company, Los Angeles Paving Company, Citrus Fruit Juice Company, and Orange County Brick and Tile Company.

A new fire hall on west Wilshire Avenue was built in 1926. It stood on what is now Half Off Books in the Wilshire Promenade building.

The Odd Fellows Temple was constructed in 1927. It remains an impressive building downtown.

In 1930, the Fullerton High School Auditorium and the new Santa Fe train station were built.

Housing

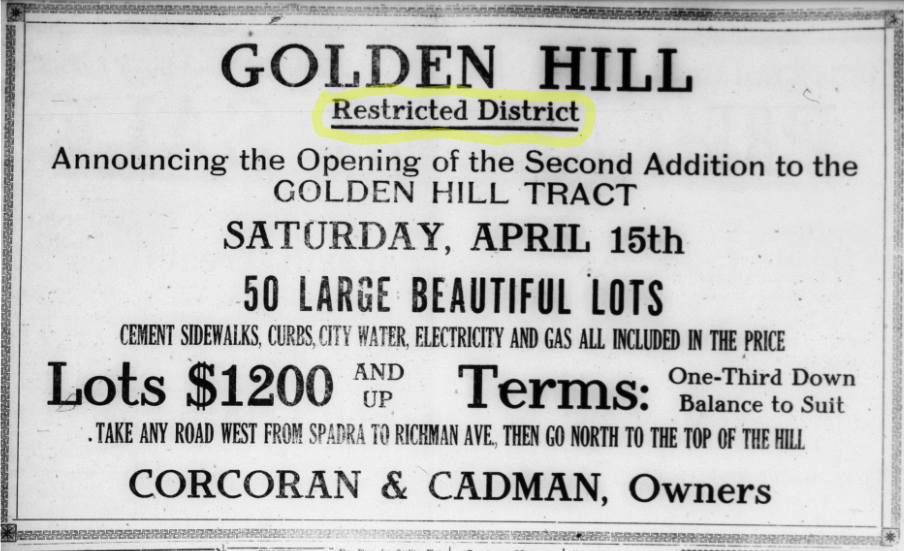

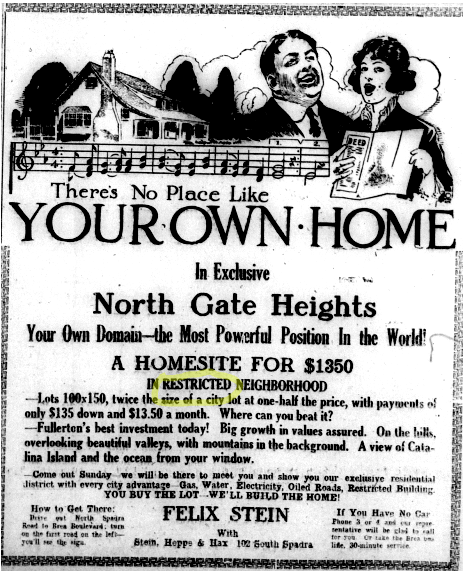

Many new housing subdivisions were built. Unfortunately, most of these had racially-restrictive housing covenants, which prevented non-whites from purchasing or renting homes there. In a recent post on this topic, Fullerton Heritage wrote:

“By the 1920s, they [racial covenants] were quite common, particularly in what is now the historic areas of the city…Fullerton newspaper advertisements for new housing subdivisions often signaled whether a tract was limited to whites only. A few advertisements were direct, but most used a coded language that potential homebuyers would understand. Words or phrases, such as ‘rigidly restricted’, ‘exclusive tract’, ‘reserved for the finest’ indicated that minorities were excluded from a subdivision.”

This is an example of systemic racism; that is, a racist policy (as opposed to individual prejudice) that was baked into the housing system. For decades, this policy made it harder for people of color to build generational wealth than it was for their white peers. This is one example of a policy whose economic impact can still be seen today, even after it was made illegal.

Below are some advertisements from the News-Tribune in the 1920s, with the “restricted” portion of each ad circled in highlighter:

Builders could not build homes fast enough to keep up with demand. This “housing shortage” created a situation of very high rents.

To alleviate this problem as new homes were being built, the Fullerton Board of Trade came up with an idea in 1922 to build temporary tent houses on the field next to the newly-built Ford School, which prospective home buyers could rent while they looked for a house to purchase.

Not surprisingly, this brought a storm of protest from surrounding homeowners.

“Like the eruption of a Mt. Vesuvius, a storm of protest has burst forth against the action of those responsible for the erection of tent houses on the West side Grammar School grounds for rent to people seeking a place of abode,” the News-Tribune stated.

A Mrs. G.F. Molleda of 317 N. Richman avenue, said, “No decent white man will put his family in a tent among low class foreigners and criminals…The hundreds of children that are supposed to be surrounded with an environment of beauty and refinement while being educated, are to be daily confronted with a view of dirty tent inhabitants and clotheslines of black, dirty rags.”

“I am speaking for all the homeowners in the vicinity of the West Side grammar school when I make this protest,” continued Mrs. Molleda, “and a petition is being prepared which will voice this protest in no unmistakable terms.”

Despite the statements from the Board of Trade that the tent houses would be neat and sanitary and “only the most desirable class of people would be permitted” to rent there, the nearby neighbors weren’t having it.

“Two hundred people signed a petition condemning the idea of increasing Fullerton’s housing capacity in this manner,” the Tribune stated. “The main points set forth in opposition being that the established of the project in this particular location would be detrimental to property interests, a menace to the school children and would tend to destroy the effect of the beautiful new school building and grounds recently created up there.”

“R.S. Gregory of the Board of Trade housing committee, under whose jurisdiction the placing of the tent houses has been left, warmly defended the action of the committee, stating in effect that the colony was not one in which undesirable people would be housed, but instead would be one in which only the most desirable class of people would be permitted to live, and these only long enough to permit them to find homes in the city,” the News-Tribune stated.

Education

As Fullerton grew, so did the need for new schools. Ford School was built in 1921. There were also additions to Fullerton Union High School throughout the 1920s.

Ford School, completed in 1922, was later torn down to make way for senior apartments and Ford Park.

Ford School, built in 1921, was later torn down to make way for senior apartments and Ford Park. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public LIbrary Local History Room. In 1924, to satisfy increasing enrollment, Maple School opened on the southside of Fullerton.

Maple School, built in 1924. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. Lottie Morse was elected to the School Board, one of the first women to hold elected office in Fullerton.

In high school news, a policy was adopted in which girls (but not boys) had to wear uniforms. This was likely a reaction to popular new clothing styles.

In 1924-25, there was serious consideration of establishing a new University of California campus in Fullerton on land that was mostly owned by the Bastanchury family. Ultimately, these plans did not pan out, and UCLA was built at its present site in Los Angeles.

Gaston Bastanchury, owner and manager of the vast Bastanchury ranch in Fullerton, created a bound proposal with lots of photos, extolling the virtues of the proposed site.

Residents of the oil towns of Brea and Olinda voted in 1925 to leave the Fullerton Union High School District and form their own.

Americanization

As Fullerton was building new schools and homes, it was also building separate facilities for its Mexican farm workers and their children under the auspices of an “Americanization” program.

“As Fullerton is the center of a great citrus and walnut growing section, many Mexicans are needed to do the work on the groves and great numbers of them are employed by the packing houses during the time when the fruit is being picked, packed, and shipped,” the News-Tribune stated in 1922. “On this account the Mexican problem has become quite a serious one, and Fullerton has been gradually increasing its facilities for handling this problem by educating the foreigner and teaching him American customs.”

“In order to promote Americanization in this community, the Bastanchury Ranch Company and the Placentia Orange Growers Association have announced their intention to Principal Plummer of the Fullerton Union High School and Junior College, to erect school houses on their properties in Fullerton,” the News-Tribune stated. “This work will commence shortly on the Bastanchury property and on the Placentia Orange Growers’ land in town and the school houses will be completed in time for the fall opening of school in September.”

Druzilla Mackey, who had done similar work at “the Mexican colony in La Habra” was put in charge of Fullerton’s Americanization program.

There were at least two “Mexican” schools in Fullerton, one on the Bastanchury ranch amidst the several work camps, and another closer to downtown Fullerton, at Balcom.

Bastanchury Ranch Mexican School. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. The downtown camp, was called Camp Progressive, and later Campo Pomona “is at present composed of twelve houses each occupied by the family of an employee of the association. Each house is equipped with toilet facilities and there are two bath houses for community use, as a central community washhouse.”

The Placentia Orange Growers Association, who paid for the camp believed “that it will not only be an asset to their business but an institution of demonstrated worth to the community.”

Despite the fact that Mexicans were generally excluded from purchasing houses in Fullerton’s neighborhoods or attending its stately new schools, the proponents of Americanization saw what they were doing as a positive, helpful thing.

A 1925 Fullerton News-Tribune article states:

The Americanization department of Fullerton Union high school is staging some very interesting demonstrations of the work accomplished in the particular field of Americanizing the aliens in the northern part of Orange County. Besides a display of the work done in the various classes, open house has been kept on certain days and the general public has been invited to attend the classes and become better acquainted with the new citizens, who are…to attain American ideals and customs.

In a tiny camp called “El Escondito” or the hidden camp…on a part of the Bastanchury ranch, one of the most successful classes is being held. This class holds an unique position as being a 100 percent class. Every woman in camp has attended each session since the school was opened and their enthusiastic cooperation with Mrs. Alma Tucker, their teacher, has produced some amazing results.

An outstanding example of this applied industry is that of Senora Guadaluope Rodarte, who has attended school eight weeks with only a two weeks absence when a new daughter arrived at the Rodarte home. With her new baby immaculately clean and in white pretty dresses, Guadalupe attends the classes each day. During the short time of her instruction she has acquired a vocabulary of about 200 words in the English language.

Dona Felipa Avilos, who has learned all the English she knows during a like period, can also converse in good English to the extent of a visit to a grocery store and the purchase of supplies.

Mrs. Tucker uses the Gonin method of teaching her pupils, but as adapted it to the local conditions, which add to its usefulness in teaching Mexicans. A new idea of using puppets to demonstrate a word or idea has been worked out by Mrs. Tucher which has proved very successful. The close cooperation and economy of the various departments of the Fullerton high school is demonstrated in this instance, for Miss Easton and Miss Bristol with their classes in art have prepared the puppets and the model houses and furniture, which Mrs. Tucker has found so useful. The class in the “Hidden Place” has a motto which is well understood and applied by the Mexican women and their teacher, and is written on the walls of the little dwelling, “Co-operation.”

In this instance the class is held at one of the Mexican homes, which although lacking many of the conveniences and sanitary additions of the American homes, is scrupulously clean with its board floor scrubbed white and pretty cretonne curtains at the windows. Flowers are in evidence both inside and outside the dwellings and in American flag is pinned to the walls of the room where the class meets.

The roll includes Gladalupe Rodarte, Marie Rodar, Isidra Avina, Rosario Gimenez, Felipa Avalos, Luciana Giminez, Maria Avila, Soledad Avalos, Maria Ramos, Aurelia Perez and Trinidad Rosales.

Occasionally students of the Americanization program showcased their progress to the community at large.

At one of these ceremonies, master of ceremonies, Crescencio Duran “distinguished himself by announcing every number in clear, well chosen English,” the Tribune reported. “Members of beginning English classes dramatized the various processes of buying and selling, while pupils in advanced English classes read original essays on Lincoln, Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Roosevelt. They had also two excellent papers on thrift, accompanied by a dramatization of how to open a savings account in English.”

To read more about the social and educational segregation of Mexican Americans at this time, check out my article “The Roots of Inequality: The Citrus Industry Prospered on the Back of a Segregated Immigrant Workforce.”

King Citrus

Despite the fact that housing and commercial development was increasing, Fullerton was still a major farming area, with citrus being king of the local crops. Many of the wealthiest local people were Orange ranchers, like Charles C. Chapman. Orange growers large and small often pooled their interests and influence with politicians to get favorable laws, such as tariffs on foreign oranges and lower freight rates.

In 1921, local growers held a massive Valencia Orange Show in Anaheim, which featured elaborate exhibits of oranges. Heading up the proceedings was Charles C. Chapman. President Harding even phoned in to praise the Orange Show.

The Orange County Fair, which still happens annually, is a testament to Orange County’s agricultural past, even though those days are long gone, having given way to urbanization and development.

The citrus industry operated in a unique way, with growers both co-operating and competing under the California Fruit Growers Exchange, also known as Sunkist.

Here’s a 1928 description of how the system worked:

One fundamental reason for the great success of the California Fruit Grower’s Exchange lies in the fact that its plan of operation effectively combines the constructive features of both competition and co-operation.

Under the Exchange system, all growers compete to produce the highest quality of fruit. The highest returns in any Exchange association go to growers who produce the most fruit per acre, or who have the largest percentage of their crops sorted into the higher-priced top grades.

Likewise each local association competes with the other 201 associations within the exchange. But the rivalry is in operating efficiency. The association that packs and handles its fruit better, builds a following for its labels and wins premiums for its gains.

Every Exchange grower and association has the maximum incentive for efficiency in management, economy in operation, and skill in method. Through this constructive competition the rewards of success automatically go to the winners in the form of higher returns.

But when the lid is nailed on a box of Exchange fruit, competition ceases and co-operation begins. The problem is then to systematically distribute all the California crop to all the markets. The real competition is not among Exchange growers and associations. It is between California lemons and Italian lemons, California oranges or grapefruit and Florida oranges or grapefruit, citrus fruits against other fruits, fruits against other foods.

In this common task Exchange growers and associations stand shoulder to shoulder.

Orderly distribution is possible only when the marketing is directed by a central organization that has all the facts about supply and demand everywhere. Marketing through unrelated agencies, each acting independently, inevitably leads to the over or under-supply of some or all markets. Sales competition within the industry can only result in lowering prices.

The achievement of the Exchange in successfully marketing the fruit of its 11,000 growers lies in the fact that it handles 75 percent of the yield.

As the percent of the crop marketed efficiency of the organization has steadily improved.

The most beneficial single thing that could happen to the California citrus industry would be to have every carload of California oranges, lemons and grapefruit marked through the California Fruit Growers Exchange.

Then there would be as much competition for quality among California growers and associations as though the Exchange did not exist.

But there would be 100 percent cooperation in perfecting the systematic distribution of the entire crop to the markets of the world…and increased returns for every grower.

What the exchange is…

The California Fruit Growers Exchange is a non-profit organization of 11,000 California citrus fruit growers, producing about 75% of the California citrus crop, operated by and for them on a cooperative basis. Its object is to develop the national and international market for California oranges, lemons, and grapefruit by continuous advertising, and to provide a marketing organization that will sell the fruit of its members most advantageously, and at least expense. Receipts from sales, less only actual costs of operation, are returned to the growers. Applications are received through all of the Exchange’s 201 local packing associations.

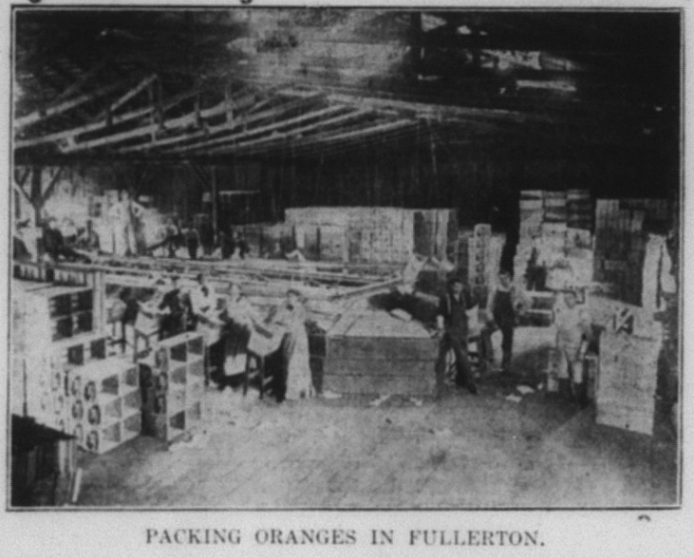

Another major aspect of the citrus industry was labor. Most of the picking of the fruit was done by migrant Mexican labor.

As they are today, these migrants were sometimes the target of politicians.

“Restriction of Mexican and other Central and South American immigration into the United States on a quota basis was urged by Rep. John C. Box, Democrat, Texas, author of a bill for this purpose, before the house immigration committee today,” the News-Tribune reported. “The country was being flooded with an oversupply of cheap labor which not only was driving out native white and colored labor in the west and southwest but also was spreading northward, Box said.”

“If I had but one reason for urging this bill it would be to protect the American farmer from a system of peasantry,” Box declared.

“Henry Deward read a statement from the immigration restriction league, Boston, urging passage of the measure and also warning that Mexican labor is spreading to other parts of the country,” the News-Tribune reported. “Chairman Albert Johnson of the committee said he had ‘hundreds of letters from prominent people not only in the west but all over the country,’ endorsed the proposed restriction.”

But not everyone wanted Mexican exclusion. Large growers from the southwest still relied largely on Mexican migrant labor, and some American diplomats felt such restrictions would negatively impact international relations.

Oil!

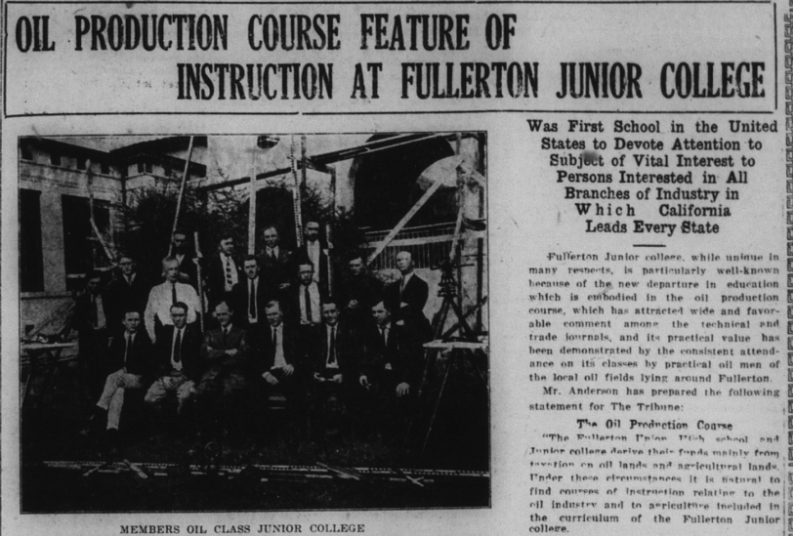

Along with oranges, oil was Fullerton’s other main export in the 1920s, with very active fields in the hills north of town that regularly brought in gushers. Fullerton Junior College began offering courses in oil production.

However, in 1921, all was not well in the local oil fields. Unhappy with wages and working conditions, Brea oil workers (who had recently unionized) voted to strike.

Perhaps the biggest news story of 1926 was the great Brea Oil Fire.

Lightning struck two 500,000 barrel underground oil reserves of the Union Oil Company a half mile west of Brea, creating a huge blast and igniting a massive oil fire.

“Plate glass windows in Brea stores were shattered by this blast which was felt slightly in Fullerton,” the News-Tribune reported. “Flames shot 500 feet in the air as the lightning struck eyewitnesses declared and burning fragments of the wooden roofs which covered the reservoirs were blown directly over the town of Brea by a strong westerly wind.”

Four hundred men were rushed to the scene to try to put out the fire and remove oil from the reservoirs. The fire threatened to spread to 10 other large tanks in the field.

Dikes were erected to halt the spread of the oil fire.

“Huge clouds of smoke billowed into the air throughout the day attracting thousands of persons from surrounding districts,” the News-Tribune wrote. “Brea fire department apparatus has been called out to protect homes near the scene of the flames and Union oil workers are moving out of their houses on the lease surrounding the tank farm as a precautionary measure.”

And then, the next day, a fourth tank caught fire.

Damage was estimated at over $5,000,000.

Fire fighters from Long Beach and Wilmington were rushed to the fire, “and workers from practically every oil field and oil company in Southern California were aiding the fight.”

To make matters worse, a cyclone struck sections of Brea causing more damage.

Finally, after a couple days of burning, the fire was gotten under control.

Ku Klux Klan

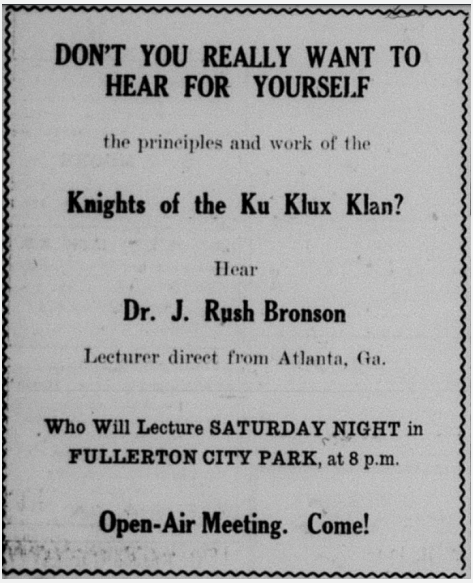

In the early 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan saw a massive resurgence, with a peak membership of around 5-6 million, with many in states outside the south. The Klan achieved real social and political power. It would ultimately make its way to Anaheim and Fullerton.

According to a 1979 UCLA doctoral dissertation entitled “The Invisible Government and the Viable Community: The Ku Klux Klan in Orange County, California During the 1920s” by Christopher Cocoltchos, “Councilman W.A. Moore, Judge French, and Superintendent of Schools Plummer [yes, that Louis Plummer] joined the Klan in the latter part of 1923, and R.A. Mardsen entered in mid-1924. Civic leaders were especially eager to join. Seven of the eighteen councilmen who served on the council between 1918 and 1930 were Klansmen,” writes Cocoltchos.

Throughout the early and mid-1920s, there are numerous articles about the growing KKK both around the country and locally.

It’s important to understand that the Ku Klux Klan saw itself as a Protestant Christian organization.

At a standing-room only sermon, Rev. C.R. Montague, pastor of the First Methodist Church of Fullerton, gave a sermon in which he (sort of) condemned the Ku Klux Klan.

However, his condemnation was only for the actions of the KKK, not their principles or values.

“While he scored the alleged acts of the Ku Klux Klan wherein that hooded body is said to have perpetrated acts of violence in an effort to remedy conditions which they believed were without the pale of law, Rev. Montague stated that he believed in fair play for them all, and expressed his entire approval of the tenets of the Klan as outlined in their published statements and oaths–allegiance to the United States government and a ‘square deal’ for every man,” the News-Tribune stated.

One of the main tenets of the Klan not mentioned explicitly in this article was white supremacy.

In order to boost their membership, the Ku Klux Klan tapped into issues that were popular at the time, such as Prohibition, which had been the law of the land since the passage of the 18th Amendment in 1919.

Bootlegging was widespread, and the KKK saw itself as a force against bootlegging.

A Klan raid on an alleged bootlegging operation in Inglewood in 1922 resulted in a policeman [and alleged Klan member] being killed and two others wounded. This prompted a grand jury investigation of the Klan’s activities locally.

Los Angeles District Attorney Woolwine sharply criticized the KKK, saying, “It seems to me that no right-thinking American could find the slightest excuse for the existence in this county of an organization such as the Ku Klux Klan.”

The grand jury found the Klan responsible:

“We, the jury, find that the deceased came to his death from a gunshot wound in the abdomen by Officer Frank Woerner in the performance of his duty while the deceased was acting as a member of an illegal, masked and armed mob, presumably instigated and directed by members of the Ku Klux Klan, and we recommend that the District Attorney convene the grand jury of this county to investigate this case further and take the necessary steps to prosecute the perpetrators of this crime.”

More arrests of Klansmen followed, as well as a raid on the KKK’s offices in downtown Los Angeles at Seventh and Broadway. As a part of this investigation, a list of Klansmen in Southern California was obtained, which revealed that the KKK had over 200 members in Orange County.

“That there are 203 members of the Ku Klux Klan in Orange county and only approximately 25 of that number are residents of other sections than Santa Ana, was the statement of District Attorney A.P. Nelson this morning,” the News-Tribune reported. “Of the Klan members outside of Santa Ana, there are said to be about 10 in Anaheim and three or more in Orange, Fullerton, Placentia, Huntington Beach and Seal Beach.”

It should be noted that this 1922 Klan list was incomplete, and another list would be discovered in 1924 that had over 1,200 names of Orange Countians.

Nelson chose not to make the names on the list public, but said he had it in his possession, should the KKK attempt further crimes.

Interestingly, like Rev. Montague, DA Nelson did not condemn the beliefs of the Klan, only their vigilante methods.

“Although stating that he thought the principles of the klan as outlined by the organization to be truly American, Mr. Nelson said that he was absolutely opposed to any organization, no matter what its principles that works by the methods attributed to the Ku Klux Klan, masked and with identities concealed to take law in their own hands,” the News-Tribune states.

After it became known that Nelson had the membership list, a mystery man appeared at his home while he was gone and tried to get his wife to get her husband to drop any further investigation into the Klan.

Meanwhile, the KKK tried to extort money from Black ministers in Los Angeles.

“Five negro ministers, one in Watts and the other four in Los Angeles, have received letters threatening themselves and their congregations with death unless they paid sums ranging from $1000 to $10,000 to the writers of the demands who signed themselves the ‘Ku Klux Klan’ according to a statement made at the sheriff’s office today,” the News-Tribune reported.

Given the growing popularity of the Klan and its threat to law and order, the Orange County Board of Supervisors voted to bar Klan members from working for the county.

“With the complete list of Klan members in the possession of District Attorney A.P. Nelson a complete check will be kept on the actions of those affected by the ultimatum of the supervisors. The names of those affected will not be made public,” the News-Tribune reported.

The resolution adopted by the Supervisors was as follows:

“Whereas, it has been called to the attention of the Board that certain employees of the county of Orange are members of and identified with the branch of that organization known as the Ku Klux Klan, and

“Whereas, the Board feels that membership in such an organization is not compatible with the duty which county employees owe to the public as servants of the public.

“Now, therefore, it is hereby resolved and ordered by the Board of Supervisors of the County of Orange, State of California, that all county employees, who are members of such Ku Klux Klan be and they are hereby requested to furnish to the District Attorney of the County of Orange satisfactory evidence of their withdrawal as members of the organization known as the Ku Klux Klan or tender to the proper officer of the county their resignation as an employee of said county.

Meanwhile in Oklahoma, an explicitly anti-Klan group formed. Because the KKK saw themselves as an “invisible empire,” this new group called itself the Knights of the Visible Empire.

“The Knights of the Visible Empire are gathering strength to oppose the white-shrouded host–the knights of the invisible realm. The Southwest is splitting into two factions–klan and anti-klan,” the News-Tribune reported. “Within the last few months the Ku Klux Klan has shown its strength. It appears to exist in every community. In the big, modern, fast-growing cities of the Southwest it numbers thousands of its “invisible empire.” This has been proved by parades and demonstrations in such cities as Dallas, Forth Worth, Beaumont, Waco, Oklahoma City, Tulsa, and other places.”

And then the News-Tribune makes a shocking, albeit buried, report:

“Here, only a few weeks ago, nearly 3,000 hooded figures passed through the streets. The parade was fifteen blocks in length. At its head masked riders bore aloft the emblem of the klan. Overhead an airplane circled, bearing a flaming cross.”

By “here” I can only assume Johnson meant Fullerton, or a nearby town.

In my previous research on the KKK in Fullerton and Orange County, I found evidence of large rallies in Anaheim and Fullerton, although I thought they only happened in 1923 and 1924. Evidently, there was also a huge Klan parade in 1922. Strangely, the Tribune doesn’t report on it outside the short paragraph above. Probably, as is sometimes the case today, some Fullertonians didn’t want to admit that the KKK was in their community, and prominent members joined.

And then, the Klan made themselves known in Anaheim.

“The first public appearance in Orange county of members of the Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, in the First Christian church tabernacle, Anaheim, last night was marked by lusty cheers of the congregation, and unlike popular beliefs was not featured by bloodshed or riot,” the News-Tribune states. “While scores sat emotionless in their seats, petrified by mingled fear and amazement, what is estimated to have been more than a dozen of the white-robed and hooded figures silently entered the edifice, presented the pastor, the Rev. C.L. Vawter, with a parcel and as silently departed.”

In 1924, the Ku Klux Klan was very active in local politics, with Klan members sweeping the Anaheim City Council majority [They would be recalled within a year].

“Significant of Ku Klux Klan activity in today’s election, a huge fiery cross lighted up the heavens last night from the hill to the westward of Northgate Heights,” the News-Tribune reported in 1924. “That the burning of the symbol had a direct bearing on the local political situation was the general opinion today.”

According to the News-Tribune, “The claim was made today by a person in close touch with local Klan affairs that there is a membership of from 2500 to 3000 in this territory.”

Ku Klux Klan rallies drawing thousands took place throughout Orange County in 1924, including at least two large meetings at what is now Amerige Park, across the street from City Hall.

The Klan was so popular, in part, because it was presented as a patriotic organization. At the above advertised meeting, the speaker stressed the fact “That it is a white man’s organization, a gentile organization, a protestant organization and an American organization in which membership is restricted to native-born American citizens. That the KKK stands for white supremacy; for the enforcement of the law by the regularly constituted authorities; development of the highest standard of citizenship; rightful use of the ballot, and the worship of God.”

At another Klan meeting that drew around 5,000 attendees, the violence that lay beneath the rhetoric almost broke out.

Local businessman Dan O’Hanlon, who was Irish Catholic, was unhappy with the Klan speaker’s denunciations of catholicism, so he shouted “Liar!” during the speech.

This led to cries of “get that guy,” “where is a tar bucket?” from different parts of the crowd. O’Hanlon was taken by police officers, for his own safety, and booked him briefly at the city jail. He was released later that night, and according to an oral history interview with O’Hanlon’s wife Margaret, a cross was burned on their lawn that night.

The Klan also made an appearance at a downtown city carnival.

“Appearing from the direction of Wilshire avenue five members of the Ku Klux Klan, robed and with raised visors, injected a little dramatic note into the street carnival last night, when they marched through the crowds of merry-makers and presented a note containing $25 in bills to E.H. Tozier, conductor of the city band,” the News-Tribune reported.

Meanwhile, the Fullerton Rotary Club passed a resolution condemning the Ku Klux Klan.

“The action of the Rotary club today marks the first tangible, public recognition of the fact that the Ku Klux Klan has become an issue here in Fullerton as it has in Anaheim and in other parts of the county, state and country,” the News-Tribune reported. “Sentiment has been greatly inflamed here of late by the secret circulation of a list of names purporting to be that of local members of the order.”

The resolution read as follows:

Whereas, a situation has developed in our fair city by virtue of the teachings and activities of the Ku Kux Klan which has set neighbor against neighbor, causing suspicion, distrust and fear to fill the hearts of many; and

Whereas such teachings and activities impede the normal development of our beautiful city, interference with the happiness and contentment of our citizens, hold us up to ridicule before the outside world, and stamp us as being a narrow, factional, intolerant, un-American people; and

Whereas the objects of Rotary International are to promote fellowship and harmony among men of all nations, to make them better business men, better professional, better fathers and in fact better citizens of the country in which they live, having as its motto, “Service above self at all times,”

Be it resolved, that the Rotary club of Fullerton, unanimously deplores the existence of such conditions and is anxious to do all in its power to restore conditions to normal so that the right to the free exercise of our constitutional rights, together with tranquility and those blessings of liberty for which our constitution was ordained and established, be guaranteed to everyone, be it further

Resolved that we hereby publicly condemn the organization known as the Ku Klux Klan, which, by its teachings and actions, tends to develop racial hatred, religious intolerance or in any way denies full constitutional rights to any of our citizens no matter what his race, religion or political affiliations may be.

Local attorney Tom McFadden spoke at the above-mentioned Rotary Club meeting, suggesting that administrators of Fullerton High School were members of the Klan.

“We must keep out all forms of intolerance in our schools,” he declared. “We must keep it out of our high school here. No one has a right to hold a position of responsibility in that institution who holds and subscribes to intolerant beliefs. There are all shades of opinion and religion in our schools and Fullerton has attained a high standing by reason of its progressiveness and efficiency. It will sink from this position if intolerant views are allowed to interfere with its operation and administration.

“A community cannot grow and prosper when its citizenry is divided by mutual distrust and suspicion,” McFadden continued. “We must restore harmony and try to re-establish friendly relations. The Rotary Clubs of Anaheim and Fullerton can do much to foster the right spirit between the two cities and in their respective communities.

“A house divided against itself can accomplish nothing,” he said in closing.

The News-Tribune stated, “Although no direct mention of the KKK was made by name in McFadden’s talk, and no particular individuals were designated, he clearly indicated by innuendo that he was concentrating his attack on members of the local high school administration whose names are declared to be on the lists which are being circulated in this city.”

Although he didn’t name him by name, McFadden was likely referring to high school superintendent Louis E. Plummer.

The Rotary Club was not the only local group opposed to the Ku Klux Klan.

“Anti-Klan forces in Anaheim are going to make a determined effort to change the entire city administration. Recall petitions are to be circulated at once, it was announced at a mass meeting held under the auspices of the USA Club…last night,” the News-Tribune reported.

Local Politics

In the 1922 midterm election, Fullerton voters elected Roy Davis (who worked at the Fullerton Ice Co.) and W.A. Moore (of the Fullerton Realty Co.). Gurman Hoppe (of the Stein, Hoppe, and Hax store) was defeated.

Sam Jernigan, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, was elected county sheriff.

1924 was an election year, and Coolidge was running for re-election. There was a proposal for Fullerton rancher Charles C. Chapman to be Coolidge’s vice presidential running mate; however, he ultimately chose Charles G. Dawes.

In the 1924 Fullerton City Council election, Harry Crooke, O.M. Thompson, and W.J. Carmichael were elected.

Meanwhile, in Anaheim, the Ku Klux Klan claimed a city council victory, electing E.H. Metcalf, Emory F. Knipe, A.A. Slabach and Dean W. Hasson. They were later all recalled.

In Brea, Harry E. Becker and Isaac Carig were elected as city trustees. “Local gossip has it that the Ku Klux Klan played a prominent role in the election backing the successful candidates and defeating the nominees of the Brea Civic League.,” the News-Tribune reported.

In 1926, J.S. Elder and Bert Annin were elected to the City Council. Harry Crooke was again chosen as Mayor. Less than a year into his tenure, Elder resigned and Emmanuel Smith was appointed to replace him. William A. Goodwin was elected town constable.

In 1928, Republican Herbert Hoover was elected president, defeating Democrat candidate Al Smith. Back then, Orange County was largely Republican. In Orange County, Hoover got 30,100 votes, while Smith got only 7,597. Hoover received 2,966 votes in Fullerton while Smith only got 542.

In the 1928 City Council election, voters chose William Hale, R.S. Elder, and O.H. Kreighbaum. Bert Annin, who was not up for election, was chosen as Mayor.

Crime

A notable criminal case in 1921 involved two Black men (E.G. Brooks and Eddie Woods) who allegedly assaulted a bus driver (Darwin O. Grimes) in Fullerton, after he tried to make them sit at the back of the bus.

“The altercation which culminated in the attack on the stage driver is said to have arisen when the negroes started to enter the second seat against the wishes of the other passenger and the driver. When the passengers objected to the negroes sitting beside them, it is said that Grimes requested that the negroes sit in the back seat, in which there was ample seating space,” the News-Tribune reported. “They refused and stated forcibly that unless the driver allowed them to sit where they chose that they would not allow the stage to depart on the trip to Los Angeles.”

After allegedly attacking Grimes, the two men fled and were later arrested. Both men pleaded not guilty, arguing that they acted in self-defense.

Before the case went to trial, the bus driver Grimes was arrested over a charge that, when he was an immigration official, he abused his power by appropriating liquor seized from an automobile (this was during Prohibition times). He had since been fired.

During the trial, Brooks and Woods said that Grimes “took a belligerent attitude which they interpreted as something of a prediction of physical force in keeping them from occupying a seat in the stage other than the rear one.”

Character witnesses were introduced for both men, among whom were S.E. Reed, Santa Fe Agent in Fullerton, F.C. Johnson, special officer for the Santa Fe, and Joe Murillo, Fullerton officer for the Santa Fe, all of whom were well-acquainted with Brooks from when he worked as a Santa Fe porter.

This was also one of the first cases in Fullerton in which women served on the jury, having recently been granted that right.

Ultimately, the charges against Brooks and Woods were reduced to simple assault and they each paid a $100 fine.

Because this was during Prohibition, the most common “crimes” were liquor-related. One of the major ironies of Prohibition was that, despite its goals of “cleaning up” America, it led directly to an increase in organized crime and political corruption.

Among other fun-killing laws, Fullerton in 1922 started cracking down on roller skating, scooters, and riding bikes on sidewalks.

Among the various crimes reported in the Tribune in 1928, one stood out to me, because it happened right around where I live, which is in former railroad worker housing near the corner of Santa Fe and Highland. A man was murdered in one of the housing units. Was it mine? The Tribune doesn’t say. But perhaps this qualifies my residence for a stop on the Fullerton Ghost Tour.

Fullerton’s First Gang

In 1921, a group of local young men (sons of prominent families) formed a gang (Fullerton’s first gang) called the Hill Rovers. They made much mischief and committed crimes such as petty larceny, breaking and entering, and theft. OC District Attorney Alex Nelson investigated the group.

Because the boys were sons of prominent local families, the DA faced pushback about prosecuting them, or releasing their names.

Ultimately, four of the gang members were arrested, and two got five years for their crimes.

An article published in early 1927 gives some crime stats from the previous year. The majority of the arrests were for booze [this was during Prohibition] or “vagrancy” (homelessness?).

The report lists three suicides, three auto fatalities, 22 arrested for disturbing the peace, four for battery, four for disorderly conduct, 21 for drunkenness, one for operating a still, 21 for possession of intoxicating liquor. 198 car accidents, 47 arrested for vagrancy.

Sometimes the perpetrators of crimes would be given names by the media, such as the Praying Sisters (bank fraudsters who sought a more lenient sentence by showing their piety), the Chloroform Burglar (who knocked people out with chloroform before burglarizing their houses), and The Fox (a murderer who killed a girl in Los Angeles and went on the run, sparking a massive manhunt).

In 1927, a county Grand Jury probe raised ethical and legal questions about top law enforcement officials. Some were accused of being in cahoots with bootleggers. A big rally at what is now Amerige Park in Fullerton called for a recall of OC Sheriff Sam Jernigan for his alleged improprieties.

The meeting was presided over by Carrie Ford, a prominent leader in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

Because, at this time, the Ku Klux Klan was a big supporter of Prohibition, some felt that the effort to oust Jernigan was a KKK plot. This rumor was dispelled by “attendees [who] said it was not a KKK plot.”

According to the News-Tribune, one attendee “challenged any members of the Ku Klux Klan to stand up and show themselves. About 20 men arose in response. The speaker then pointed out that more that 90 percent of the persons at the meeting were not of the Klan.”

This is fascinating to me because it shows that the KKK was still a conspicuous presence in local affairs, even after its popularity began to wane after 1925.

Prohibition

In 1919, Congress passed the 18th amendment to the U.S. Constitution (and the subsequent Volstead Act), banning alcohol. Locally, city council passed ordinances to help with enforcement of the Volstead Act and curb violations of the law.

One way that people sought to get around prohibition was to have doctors prescribe them liquor for “medical” reasons. On more than one occasion, police rounded up and arrested such violators.

Bootlegging was also fairly widespread, so raids and arrests were not uncommon.

The noted Bastanchury family had made their own wine for years. They were raided and some charged with violating the dry law.

Nearly every issue of the Tribune throughout the 1920s has a story about people being fined or arrested over illegal booze.

Although they had achieved their goal of national Prohibition, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was still active, presumably because lots of people were still drinking.

One way the Ku Klux Klan gained popularity was by adopting popular positions on hot-button issues. In addition to being opposed to racial minorities, Catholics, and Jews, they were also in favor of restricted immigration and prohibition.

In 1924 the Klan and their supporters worked with local and federal law enforcement to conduct a massive arrest of bootleggers. The headquarters of the massive raid was the ranch of Fullerton pharmacist William Starbuck.

In what proved to be a dumb move, these anti-bootleggers then presented a bill to Fullerton city council for $2,800 to cover the costs of the raids (they hadn’t bothered to inform city council of the raid in advance). City Council refused to pay, as did other local city councils who received similar bills.

The Fullerton police department occasionally held public “booze pouring” events in which they dumped out hundreds of gallons of illegal booze they had seized.

And then, something embarrassing happened. Some Fullerton police officers were accused by another officer of stealing wine from the department’s stock of seized liquor for personal use.

After a few public hearings before City Council, the accused officers denied any wrongdoing and were not convicted of any crimes. The whole ordeal, however, caused a shake-up in the department, in which some officers were forced to resign.

Adding to the embarrassment, Fullerton City Councilmember Emmanuel Smith and beloved football coach “Shorty” Smith were both arrested and fined on liquor charges. Neither lost their jobs. By criminalizing a hugely popular activity, prohibition highlighted the hypocrisy of leaders [President Harding famously served and drank booze in the White House], and made the United States way more corrupt at all levels of government–from federal to local.

Sports

In sports news, baseball was quite popular locally. In addition to high school baseball, teams would play at the field on what is now Amerige Park.

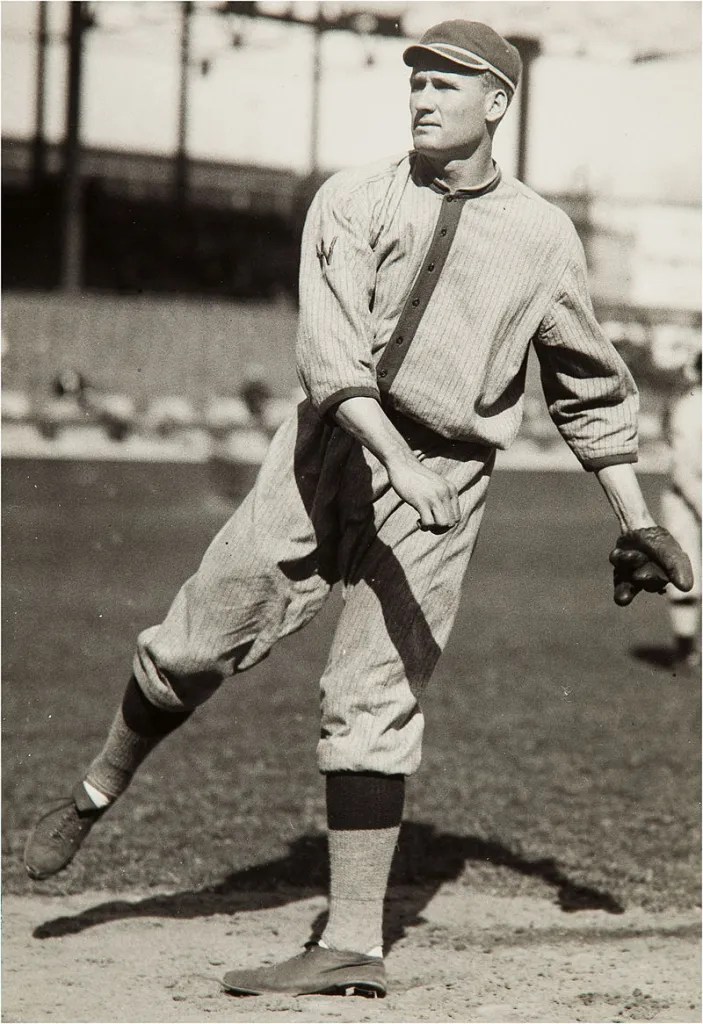

By far, the biggest local sporting event of the decade was a 1924 exhibition game in Brea featuring baseball legends Walter Johnson (who went to Fullerton High School), Babe Ruth, and other big-league players which drew around 15,000 spectators.

Local athlete Glenn Hartnraft placed second in the shot put at the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris.

The mascot of Fullerton High School was, and is, the Indian. In more recent years, this has proved controversial, as native American groups over the years have tried to get the district to change the mascot, arguing that it is offensive. Despite the fact that activists have been unsuccessful in changing the name, I too find it offensive, especially considering the fact that throughout the 1920s, the Fullerton Indians were regularly called the “redskins” and the “red men”. The school would host “Pow Wows” featuring non-native people dressing up as Indians. These “Pow Wows” were still happening as late as the 1990s, when I attended high school there.

In 1928, Gaston Bastanchury, owner of the sprawling Bastanchury Ranch in the hills of north Fullerton, wanted to build an enormous venue to host a boxing match between world champion Jack Dempsey and Basque boxer Paulino Uzcudun, who would train on the ranch. Unfortunately, this never came to fruition.

In 1929, local baseball star Willard Hershberger was drafted into major leagues by the Washington Senators.

Golfing, both regular and miniature was popular locally, with the following courses:

Culture and Entertainment

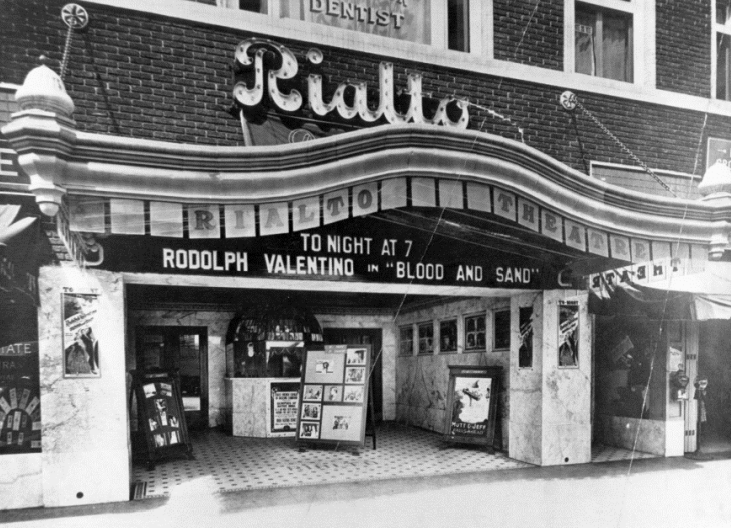

Prior to the opening of the Fox Theater in 1925, locals would go see movies and Vaudeville shows at the Rialto Theater downtown.

Rialto Theater in downtown Fullerton, 1920s. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. In 1921, Fullerton’s new Masonic Temple (now the Springfield Banquet Center) was formally inaugurated and its first officers chosen. In the early 20th century, fraternal organizations like the Masons and Odd Fellows were very popular.

Another popular form of entertainment in the 1920s was the traveling Chautaqua show, which featured musical performances, speeches, and more. The show came through Fullerton every year.

The other big gathering in the 1920s, outside of Klan Rallies, was the Armistice Day parade, celebrating the ending of World War I. This was a truly massive annual event, with thousands of attendees and hundreds of floats!

Unfortunately for movie-goers, Will B. Hays (former Postmaster General under president Harding) was hired in 1922 to censor movies of content deemed objectionable.

“A genuine ‘spring cleaning’ to purge motion pictures of all semblance of salaciousness was promised today by Will B. Hays, who leaves President Harding’s cabinet March 4 to head a new association of motion picture producers and distributors,” the Tribune reported.

“I will head what you might term a moral crusade in the film industry after March 4,” Hays said, adding that this would not be censorship. “I have two objects. We will attempt to attain and maintain the highest standards in motion picture production and seek to develop the moral and educational values of motion pictures to their highest degree. That is all we plan.”

Much of the discussion centered around depiction of sex in movies. There was much less discussion about depictions of violence. I always have found it ironic that many Americans tend to be much more averse to depictions of sex than depictions of violence in movies. We are generally more comfortable watching an action hero kill dozens of people than we are watching two people be intimate. This means something.

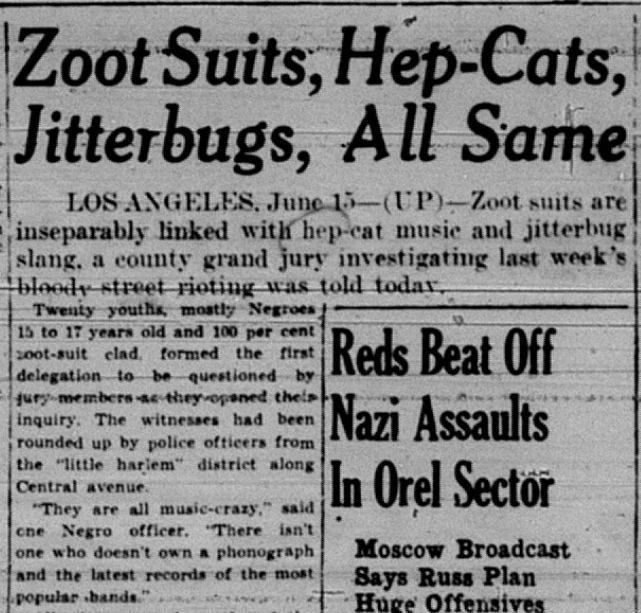

Just as there was something of a moral panic about sex in movies, there was also backlash against the influence of jazz music.