-

A History of the Fullerton Police Department

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Introduction

As part of my research into Fullerton history, I have created a number of mini-histories that will eventually be integrated into a larger narrative. Some mini-histories I’ve written so far cover such local topics as Hawaiian Punch, Hughes Aircraft, Cal State Fullerton, Maple School, and more.

I have recently completed writing a history of the Fullerton Police Department. The first source I read was an official history of the department published in 2002 by the Fullerton Police Officers Association. While this gives a broadly accurate narrative and includes lots of useful facts and notable people, it leaves out anything negative about the department. I have sought to supplement this history with news articles I obtained in the Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library, and others online. Another excellent source of information was a memoir written by former Fullerton police officer Phil T. O’Brien called Bullets, Badges, and Bullshit. O’Brien, who worked for the FPD from 1961 to the early 1990s, offers some useful color to a story that might otherwise feel kind of dry.

My hope is that, by synthesizing these diverse sources, I am able to give a more well-rounded picture of the department over the years. This history is, of course, incomplete, but I’ve tried to include as much information as I could find.

Early Days

In the latter half of the 19th century, prior to the formation of the town of Fullerton in 1887, the area was sparsely inhabited by a few farming families. Anaheim had a town constable, but there was no regular law enforcement presence in the area that would become Fullerton. Crime was limited to the occasional “bandit” roaming the area between Los Angeles and San Diego.

“The only law enforcement for the area was the LA County Sheriff’s office out of downtown Los Angeles,” according to FPD’s official history. “The new settlement of Fullerton was a one-day ride on horseback for the assigned lone deputy.”

For a few years after Fullerton was founded in 1887, there was no law enforcement. Saloons and rowdiness downtown created the push for some police presence.

“A number of roughs, hailing from everywhere, make it a point to come to Fullerton every Sunday, and after imbibing a library quantity of tarantula juice proceed to paint the town a bright, brilliant, carmine tint,” the Fullerton Tribune reported in 1893. “They do this with the knowledge that we have no peace officer in this section, and accordingly they have no fear of arrest. We need a constable and a justice of the peace. Anaheim, a small village a few miles south of here, has two of each.”

Eventually, A.A. Pendergrast was appointed as the town’s first constable. Pendergrast, taking ill with rheumatism, was replaced by James Gardiner, son of pioneer farmer Alex Gardiner. Tragically, James died of pneumonia after risking his life to save a young girl during a flood in 1900. He was replaced by Oliver S. Schumacher.

In 1904, Fullerton incorporated as a city, creating an official government. The first elected town marshal was W.A. Barnes. However, he resigned that same year, overwhelmed by the workload which (at that time) included supervising all roadwork and being on duty from 7am to midnight.

City Council appointed orange and walnut grower Charles E. Ruddock to finish the term for which Barnes was elected. Ruddock was re-elected in 1906. That same year, Fullerton residents voted to go “dry”—and outlaw saloons in town, which had been (and would continue to be) a point of contention and fierce debate.

Charles E. Ruddock Ruddock was re-elected in 1908. He expanded the department by appointing four deputies. He “retired” in 1910, and ran (successfully) for Orange County sheriff in 1914.

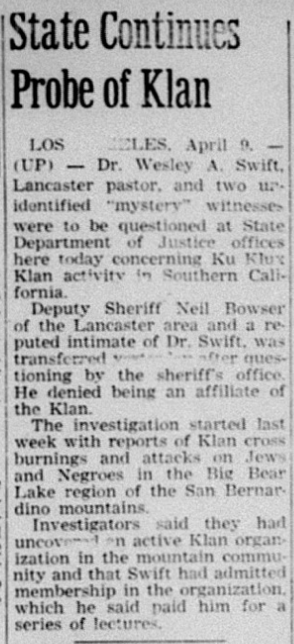

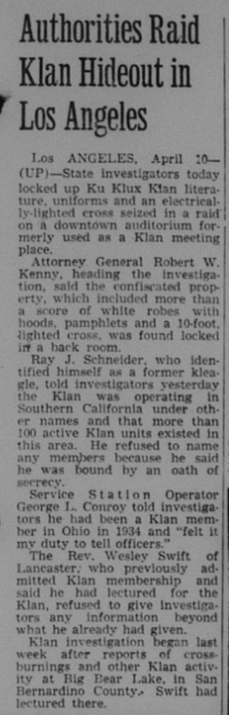

In 1910, Roderick D. Stone was elected town marshal. He left in 1912 and was replaced by William French, who would eventually become a local judge. It was during French’s term that the title of “marshal” as changed to “chief of police.” William French allegedly joined the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, along with many other cops and local leaders.

In 1914, Fullerton police got their first official uniforms.

Vernon “Shorty” Myers was elected police chief in 1918. That year, the first motor cops hit the streets, riding Indian motorcycles. In 1919, a new city jail was built.

The 1920s

Arthur Eeles became police chief in 1922. A former Deputy OC Sheriff, Eells had been a sharpshooter with the 364th Infantry during World War I, surviving a mustard gas attack in France.

In 1925, Eeles was asked to resign following a local controversy involving Ku Klux Klan members conducting their own vigilante raid on suspected bootleggers. Eeles was thought to be in league with the Klan.

In the mid-1920s, the Ku Klux Klan had a large presence in Orange County, including Fullerton. Their members included police officers, city council members, judges, teachers—white protestant men from all walks of life, including many prominent community leaders.

A new chief, O.W. Wilson, replaced Eeles. An academic as well as a law man, Wilson would later go on to become a well-respected pioneer in policing, teaching at Harvard and serving as police chief of Chicago.

But he didn’t last long in Fullerton and left the same year he began. He was replaced by Thomas K. Winters, who served for two years, being replaced by James M. Pearson in 1927, who would serve for 13 years.

In those early decades, police chief turnover was quite high, likely a result of the chief having to run for re-election every two years. It appears that some time during Pearson’s term, the police chief went from an elected position to one appointed by city hall because he was the first in a series of longer-tenured chiefs.

During the 1920s, Prohibition was in full effect, and local law enforcement struggled to control bootlegging.

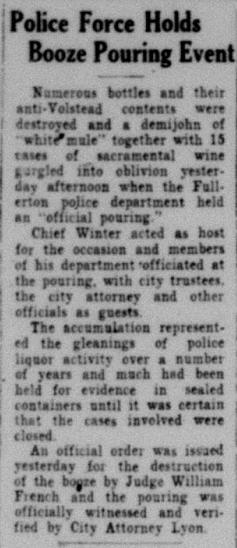

The Fullerton police department occasionally held a public “booze pouring” events in which they dumped out hundreds of gallons of illegal booze they had seized.

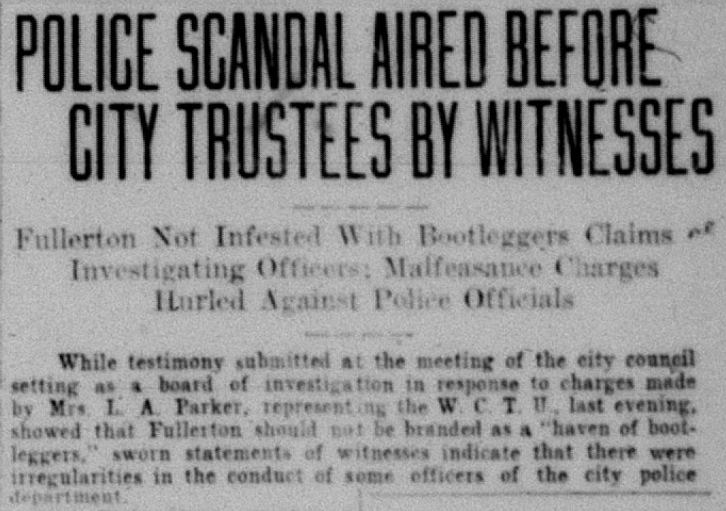

Fullerton News-Tribune, 1926. And then, in 1926, something embarrassing happened. Some Fullerton police officers were accused by another officer of stealing wine from the department’s stock of seized liquor for personal use.

Fullerton News-Tribune, 1926. After a few public hearings before City Council, the accused officers denied any wrongdoing and were not convicted of any crimes. The whole ordeal, however, caused a shake-up in the department, in which some officers were forced to resign.

Adding to the embarrassment, Fullerton City Councilmember Emmanuel Smith and beloved football coach “Shorty” Smith were both arrested and fined on liquor charges. Neither lost their jobs.

By 1929 the force was made up of eight men: Kenneth Foster, Frank Moore, RC Mills, SR Mills, JH Trezise, John Gregory, Jake Deist, Ernest Garner, and Chief Pearson.

Prior to radios and walkie-talkies, communications between the police station and officers on duty was conducted by a series of call boxes and lights atop tall buildings downtown—sort of like the Bat signal.

The 1930s

In the 1930s, the Fullerton Police Building and jail was located at 123 W. Wilshire Ave, just behind the fire station. It had three rooms—the chief’s office, the report dest, and the jail cell which had eight bunks.

In 1936, Fullerton Night School began offering a special course for police officers.

That same year, thousands of local Mexican citrus workers went on strike. Hundreds of law enforcement (including sheriff deputies and those from surrounding cities) battled with the strikers in what was the most intense labor conflict in Orange County history.

Fullerton News-Tribune, 1936. The FPD made local headlines in 1937 when Ernie Garner arrested two bank robbers who were on the run, although it was mostly just luck. One of the robbers fell asleep at the wheel and crashed the car right in front of Garner a block from the police station.

Officer Ernest Garner (center) poses with two bank robbers. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. According to the official FPD history, “In the 1930s, the majority of calls was for drunks, fights, and citrus-related thefts. The patrolmen spent most of his day interacting with the downtown merchants as this was the hub of activity for the small town.”

The 1940s

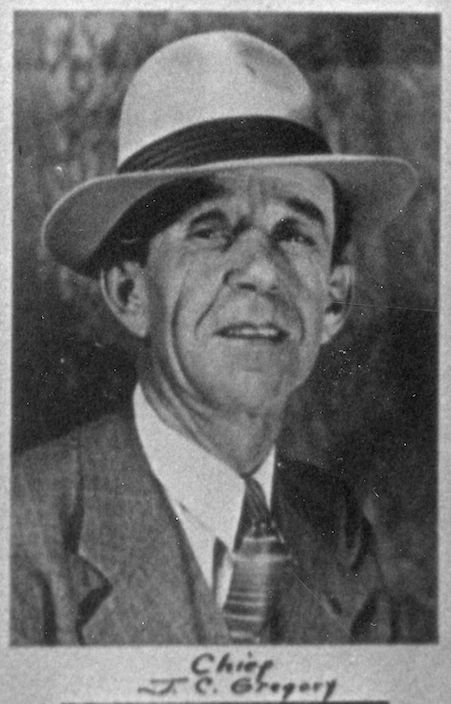

Chief Pearson retired in 1940 and was replaced by John C. Gregory, who modernized the department with a record-keeping system modeled after the FBI’s.

During World War II, the city established a Police Officer Reserve Corps, air raid wardens, a home guard, and a civil defense council.

After the war, Fullerton entered a period of rapid growth, necessitating more police officers.

“In the 1940s, the type of calls for service changed dramatically. Crime became more frequent as did the instance of violence. The calls for service started to include robberies and burglaries,” according to the official police history. “Traffic accidents were also on the rise with the influx of the population. The small justice court which was held in the city council chambers was outgrowing the facility. The municipal court system was set up to relieve the pressure of the individual justice courts throughout the county.”

In 1941, Fullerton celebrated the completion of a brand new city hall on W. Commonwealth and Highland Ave. The Spanish-style WPA building also housed the police department. Today, it is completely occupied by the police.

Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. The 1950s

In 1951, police chief John Gregory retired and was replaced by Ernest E. Garner, who had served in the police department since 1928. The department had 21 employees.

Chief Ernest Garner poses with the Fullerton Police Department, 1950s. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. In the 1950s, as the city continued to grow, the first police radio cars were put into service.

In 1955, the Fullerton Police Benefit Association (a sort of proto-union) was formed to give services to officers, including loans, insurance, and to promote social activities.

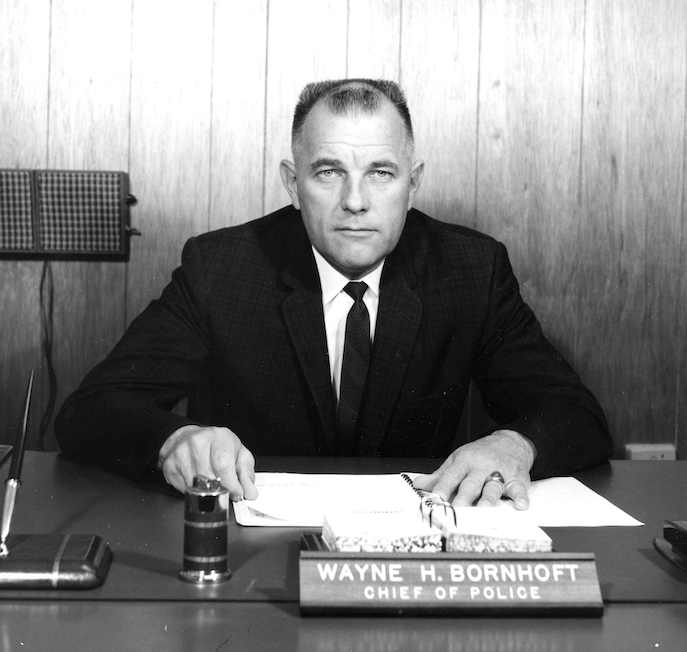

Chief Garner retired in 1957 and was replaced by Wayne Bornhoft, who would serve for many years and leave an indelible mark on the department. Today, the Fullerton Police Station is named in his honor.

Bornhoft was instrumental in establishing the Fullerton Police Training School in 1960. He served as President of the California Peace Officers Association, and was appointed by governor Reagan to the California Council on Criminal Justice.

Chief Wayne Bornhoft. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. According to O’Brien, Chief Bornhoft “never left any doubt in anyone’s mind was to who was in charge of the Fullerton Police Department. He was an authoritarian figure who ruled with an iron fist.”

Fullerton hired its first female police officer, Geraldine K. Gregory, in 1959. She worked in the Investigation Division in cases involving juveniles and women.

Geraldine K. Gregory, Fullerton’s first female police officer. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. That same year, 1959, the Fullerton Police Training Academy was formed.

The 1960s

In the 1960s, the Fullerton Police Benevolent Association became more like a real union, with its president being the chief negotiator with the city regarding salaries, benefits, and working conditions.

In response to concern over increased recreational drug use, the FPD established a narcotics bureau in 1967. Ironically, according to officer O’Brien, the drugs of choice for Fullerton Police were alcohol and steroids.

Fulleton in the 1960s was a pretty conservative town. Officer O’Brien, who was hired in 1961, reflected the conservative establishment’s disdain for the hippie and counterculture of the era.

“Long hair on a male soon became a reason for a shakedown,” O’Brien writes. “Probable cause for a car stop, a pedestrian check, or a pat-down search for drugs or weapons was often listed in reports as simply, longhair.”

O’Brien gives a fascinating account of clashes between police and hippies in the late 1960s at Hillcrest Park, which had become a popular gathering place for young people, rock concerts, and recreational drug use.

“The bowl area became a gathering place for dirt-bag hippies and dopers,” O’Brien writes. “They soon began homesteading the park and made it such an undesirable place that families could no longer go there. We would run them out and make arrests whenever possible, but the situation continued to worsen, and the numbers of troublemakers grew.

Eventually, City Council passed ordinances to close the park at night, prohibit camping, sleeping, and/or “protracted lounging.”

Here’s O’Brien’s account of a final confrontation between the police and the hippies in 1969 at Hillcrest Park:

“More and more dirt-bags poured into the park from all over the state. They began to refer to it as ‘The People’s Park.’

The situation came to a head one day after the news media had advertised far and wide, that on that day the Fullerton Police Department SED Squad [a precursor to SWAT] was closing down the park and would arrest anyone who failed to leave. The less than desirable inhabitants of the park looked upon this declaration as the ultimate challenge. The publicity attracted literally thousands, including newspaper reporters and television crews. Also present were the Mayor, the Police Chief, the Fire Chief, and several fire rigs, paramedics, ambulances and even a few civil rights groups.

We embarked on the task of routing this mob out of the park. They were in the trees, in the bushes, and had homesteaded every conceivable bit of space…It turned into a snipe hunt, and was soon a matter of officers in terms of two or three going after the most flagrant violators.

We were stormed with rocks, bottles, bricks, metal pipes, etc…The battle that day went on for hours, and extended out of the park, through a residential area, and south of Lemon Ave not the Fullerton College campus. A new line was established at Lemon and Berkeley to keep people from filtering back up into the park.”

Eventually, the “People’s Park” was cleared of “dirtbag hippies.”

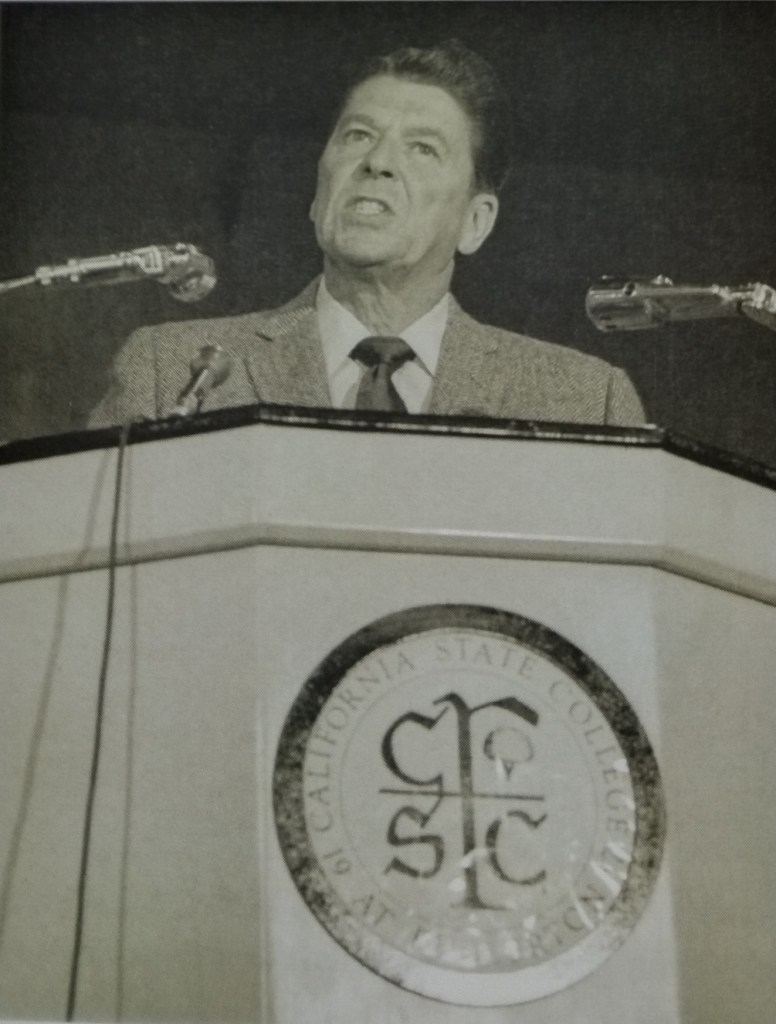

Another confrontation between the youth and the police occurred at CSUF in the Spring of 1970, when an appearance by Governor Ronald Reagan sparked a series of student protests that drew thousands, lasted for weeks, and involved the occupation of campus buildings.

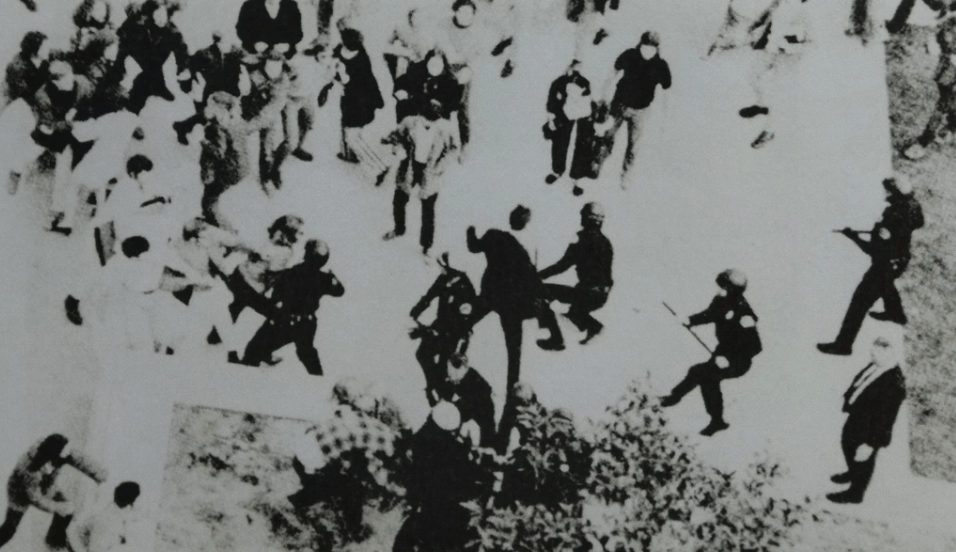

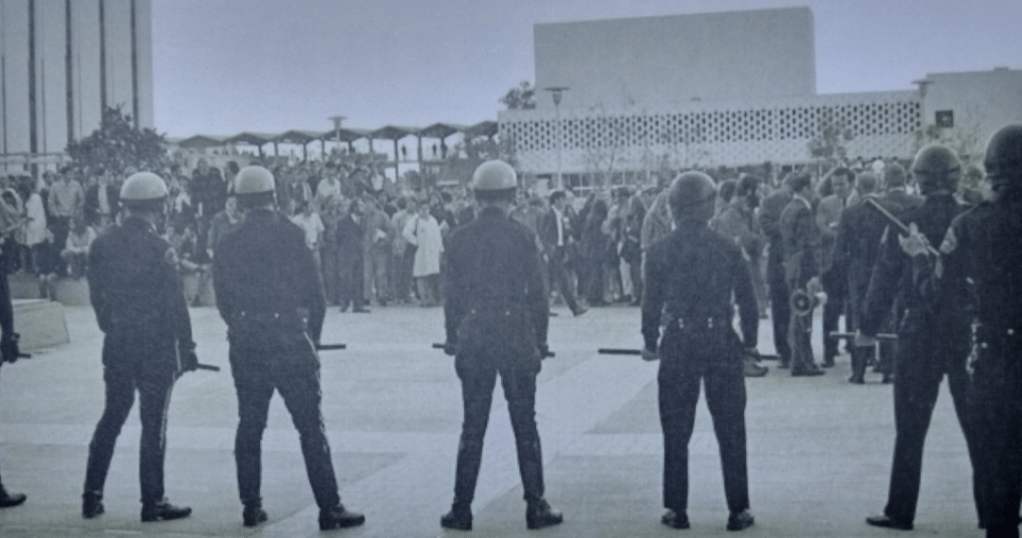

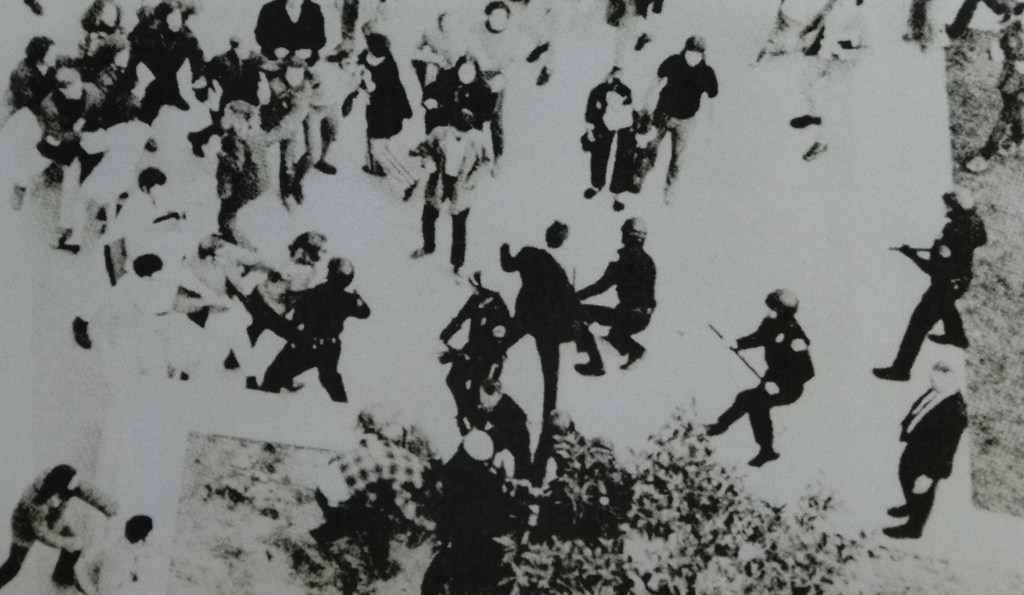

Fullerton police SED squad at CSUF, 1970. “During this same period of unrest throughout the nation, many agencies began to form and train special riot control squads,” O’Brien writes. “Fullerton was among the first, if not the first in Orange County to form what was called the Special Enforcement Detail (SED)—it was a forerunner to SWAT.”

O’Brien was on the original SED squad sent in to quell the CSUF protests.

“When we arrived on campus there was a crowd of about 2,000 people,” O’Brien writes. “During the exchange that took place after we moved into the crowd, several officers were injured, but none seriously. A number of students and other participants were also injured.”

Police and students clash at CSUF, 1970. Click HERE to read more about the 1970 student protests at CSUF.

As a member of the SED squad, O’Brien was also called in to quell such countercultural events as a hippie festival at Disneyland (including the legendary “Pot Day on Tom Sawyer’s Island”), and the massive 1970 Laguna Rock Festival.

The 1970s

The Department established a “community relations bureau” in 1971, which eventually included the D.A.R.E program instructors, School Resource Officers (SROs), and the Neighborhood Watch program.

In 1974, the department was expanded with a $1.4 million building.

Chief Bornhoft encountered some controversy when he ordered the investigation of an alleged bribery attempt from a housing developer and a City Councilmember, which prompted the council member to try to get the chief fired.

“I have no apologies to make to anyone,” Bornhoft said of the investigation. “That’s the way government should function. There should be checks and balances. I don’t believe that just because an official is an elected official and he is possibly involved in a criminal offense, I can walk away from it and let someone else do it. I feel it is my responsibility to investigate it.”

According to a 1977 LA Times article, Bornhoft’s reign “has been marked by controversy. A sizable segment of the community has supported Bornhoft, seeing him as a conservative, iron-willed, law-and-order chief. His supporters contend that the streets have been safe and the crime rate has held at a modest level. Others however contend that Bornhoft was not sensitive to the problems of minorities and unable or unwilling to communicate with the people.”

Bornhoft retired in 1977, and was replaced by Martin Hairebedian, a 23-year veteran of the LAPD.

Chief Martin Hairabedian was fond of leisure suits. By the 1970s, the Fullerton Police Officers Association was becoming a more powerful union which negotiated with the city for higher pay, benefits, and working conditions.

“In 1979 the association fought for and won a 30% single year increase,” according to the FPOA history. “The members not only walked the picket line in front of city hall but they also rallied the business community.”

The 1980s

In 1983 the FPBA changed the name to the current Fullerton Police Officers Association.

When Martin Hairabedian retired in 1987, Philip Goehring became chief of police. He had worked for the department since 1961. He got a law degree in the 1970s and taught police science courses at Fullerton College.

“The department had a bad reputation in the community,” Goehring said upon taking over the department. There had been 75 citizen complaints registered against officers the year he arrived.

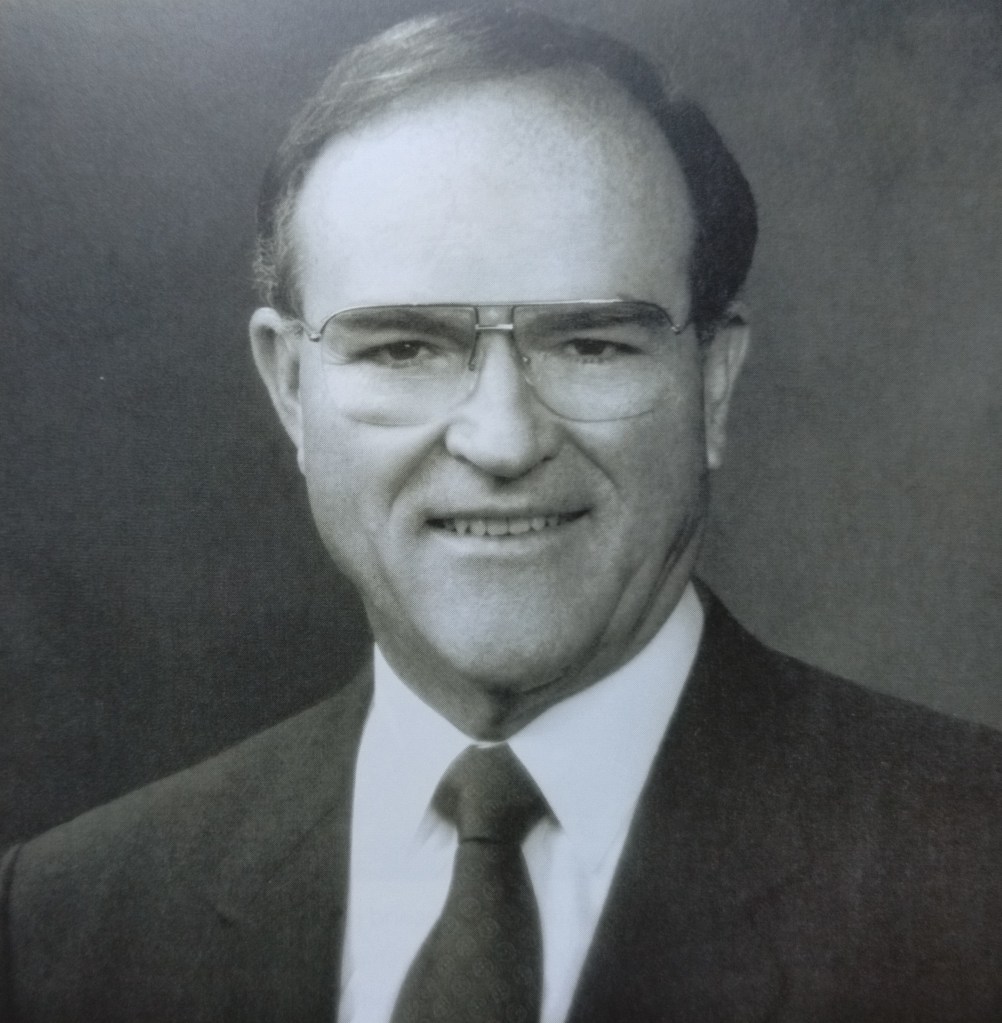

Chief Philip Goehring. While he was chief, Goehring created the first written policy manual and oversaw automation of police records.

The 1990s

In 1990, tragedy struck the Fullerton Police Department when undercover officer Tommy De La Rosa was killed in Downey in a drug bust gone bad.

Thousands attended De La Rosa’s funeral and years later a street was named in his honor.

Thousands attended the funeral for slain FPD officer Tommy De La Rosa. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. During the 1992 LA riots, some FPD officers were sent to assist the LAPD and the National Guard. Ironically, the LA Riots began because an all-white jury acquitted the LAPD officers who were caught on tape brutally beating Rodney King.

In 1991, Chief Goering became engulfed in controversy when it was revealed that he had written a letter to the District Attorney on behalf of his friend’s son, who had been convicted on a drug charge.

“With the memory of Tommy de La Rosa, a popular Fullerton narcotics detective murdered in an ambush this past summer in Downey still fresh in their minds, Goering’s rank and file officers were outraged when the letters became known,” the Fullerton News-Tribune reported.

Despite an official apology, Goering’s officers had begun to lose faith in him, and he retired in 1992.

In the early 1990s, the Fullerton Police Department created a program called “Operation Clean-Up” which was (initially) focused on improving quality of life in a few Latino-heavy neighborhoods in south Fullerton that were experiencing the impact of local gangs.

Initially, the program involved sending officers on mountain bikes into the neighborhoods to attempt to build a better rapport with the community. This was an attempt at “community policing.”

Lieutenant Tom Bashan told the Fullerton News-Tribune, “When I first started [police work], it was ‘we against them.’ That attitude is gone. You get to know who the people are, you know most things about them, you start developing other ways of handling people besides strict enforcement.”

The program seemed off to a good start, even winning a Governor’s Award.

In 1993, Pat McKinley, a 29-year veteran of the Los Angeles police Department, was chosen to become Fullerton’s next Chief of Police.

Chief Pat McKinley. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. McKinley had been involved in the formation of the LAPD’s SWAT squad, which was the first in the nation. It was created following the 1965 Watts Riots and was an important step in militarizing the police, and ramping up aggressive policing tactics.

It was under the leadership of Pat McKinley that the community policing activity of “Operation Cleanup” took a much more aggressive turn.

The Fullerton Police department conducted an aggressive “sweep” of over 33 homes in the Maple area of South Fullerton, breaking down doors of suspected “drug dealers” and terrorizing families.

Reporting for the OC Weekly, Nick Schou wrote that the department “adopted operations reminiscent of Vietnam: an occupying army bent on separating the ‘bad guys’ from the ‘responsible’ population it claims to protect—and, at the same time, using brutal tactics that tend to punish both groups in equal measure.”

Image courtesy of the Fullerton Observer. Following the sweep, McKinley faced a room full of angry residents at a meeting at the Senior Center.

An elderly Mr. Alberto Sambrano said, “I have lived here since 1939 and I have never seen anything like this before, the way they treated my 70-year-old wife. They destroyed my garage, a dresser in the house and a tool shed. We were treated like animals. They handcuffed my grandson Jonathan Navarro, who has never been in trouble. They took a gun my dad had given me 50 years ago.”

“Officer #1037 pulled my disabled brother up from his hospital bed and threw him on his wheel chair,” Gloria Hernandez told the chief.

Maple area resident Bobby Melendez said, “Use of stormtrooper tactics by the police and physically & verbally abusing people in their homes is not a minor matter.”

Charges of excessive force also occurred when heavy-handed police tactics were used against mostly Latino students from Fullerton College and local high schools during a protest.

“More than 20 students suffered slight injuries when Fullerton police, assisted by officers from several neighboring cities, used pepper spray and arrested six people, ending a rally and march of about 300 students who were demanding more Latino educators and more Chicano studies in schools,” the LA Times reported.

Los Angeles Times, 1993. Apparently the protest, which had started at Fullerton College, turned into a March through Fullerton streets, and ended with a clash with police near Lemon street.

“One of the girls in front of me was hit with a baton and it hit me on the side,” Grace Ruiz, a 15-year-old high school student said. “The police didn’t need to hit us with their batons or spray us with pepper spray.”

In 1994, the Fullerton Police Officer’s Association (the police union) started a Political Action Committee to funnel money to City Council Candidates they felt would support their interests, and occasionally oppose candidates they did not want. This PAC remains an important source of campaign contributions.

The 2000s

In 2000, the FPOA-PAC endorsed Chris Norby and Mike Cleseri for City Council. They were rewarded with a new contract that brought about the “3% at 50 retirement package” and a significant pay increase. In 2000, the FPD got a new a new high-tech crime lab.

In 2002, the FPOA-PAC supported Don Bankhead, Leland Wilson, and Shawn Nelson for City Council. They all were elected.

In the early 2000s, a new subculture caught the attention of the FPD–rave culture.

“Hours after 250 undercover narcotics officers finished an intense Rave Parties seminar at Fullerton City Hall last Friday, local police found signs of the Hollywood club culture at a local nightclub and high school dance,” the Fullerton News-Tribune reported.

“This is one scary culture,” said Fullerton Police Sgt. Joe Klein, president of the Region V chapter of the California Narcotics Officers Association, sponsors of the two-day workshops.

Apparently, Fullerton club In Cahoots came under fire for hosting rave nights.

Following 9/11, the North Orange County Regional SWAT team was organized.

In 2004, the Fullerton Police Department got a $12 million renovation.

Chief McKinley retired in 2008, and was replaced in 2009 by Michael F. Sellers.

“I have always told my officers that we have three jobs,” Sellers said. “Our first step is to save lives. When lives are not at stake, our next job is to protect life. When that’s not an issue, our job is to help improve the quality of life for our citizens, and that is done through community-oriented policing.”

At the time of his hiring, Sellers taught classes in ethics, leadership and community-oriented policing at Fullerton College.

The 2010s

In 2011, Sellers’ ethics and leadership were put to the test when six Fullerton police officers were caught on video brutally beating a homeless man named Kelly Thomas to death.

Kelly Thomas in better times (left) and after beating by FPD (right). Local residents began to flood City Council chambers and organize weekly protests outside the police department, demanding accountability for the killing of Thomas.

Justice for Kelly Thomas protest, 2011. What did Sellers do? He went on disability leave one month after Thomas’ death, and then retired.

Capt. Kevin Hamilton was selected to serve as acting chief, and then he retired.

Two officers, Jay Cicinelli and Joe Wolfe, faced criminal charges over the death of Thomas, and the department faced three internal investigations by a special consultant. Both Cicinelli and Wolfe were ultimately acquitted, sparking one of the largest protests in Fullerton history.

Also, as a result of their perceived lack of leadership after the death of Thomas, three City Council members, including former Chief Pat McKinley, were recalled by the voters.

Dan Hughes, a 28-year veteran of the department, was appointed Police Chief in 2013.

Although the Kelly Thomas case was the highest profile incident of police brutality in the 2010s, there were others, such as the cases of Veth Mam and Edward Miguel Quinonez, both off whom were attacked by officer Kenton Hampton, who was also involved (but not indicted) in the Kelly Thomas case.

Officer Albert Rincon was accused of sexually assaulting several women in the back of his cruiser. And in 2012, corporal Vincent Mater was found guilty of destroying evidence after a man committed suicide in his cell at the Fullerton Police Department.

Dan Hughes retired early in 2016 after allegations that he gave special treatment to former City Manager Joe Felz, who drunkenly crashed his car into a tree after an election-night party and then attempted to flee the scene.

Hughes was hired as VP of security at Disneyland. The District Attorney filed a felony charge against former police Sergeant Rodger Jeffrey Corbett for falsifying a police report about the Felz incident.

Hughes’ replacement as chief was David Hendricks who (not long after being hired) got into hot water after drunkenly assaulting an EMT outside a concert in Irvine in 2018. He was charged and pled guilty.

Hendricks was released and replaced by Robert Dunn.

The 2020s

In 2020, Fullerton Police Officer Jonathan Ferrell shot and killed resident Hector Hernandez. This sparked years of protest by Hernandez’s family and community members. Although the DA declined to file charges against Ferrell, the city paid out an $8.6 million settlement to Hernandez’s family. This indicates a pattern in which officers who kill people in the line of duty rarely face criminal consequences, but sometimes (if there is enough public outcry) the city (aka the taxpayers) will pay out millions to the family of the deceased.

Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Observer. Also in 2020, following the death of George Floyd, there were large-scale protests and rallies for justice and police reform, including here in Fullerton.

Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Observer. In 2021, the Fullerton Police Department collaborated with other local agencies to create Project HOPE, with the purpose of doing more proactive outreach to the local homeless community. This program still exists today.

Because of a general lack of an adequate social safety net for the homeless, the job often falls to the police to deal with a social problem that they are ill-equipped to deal with. Sometimes the police collaborate with social service agencies (as with Project HOPE), and other times the police are asked to be strict enforcers–clearing homeless camps, arresting the homeless, and sometimes (as in the cases of Kelly Thomas and Jose Luis Naranjo Cortez, brutalizing them).

In 2023, Chief Dunn left the department and Capitan Jon Radus became Fullerton Police Chief.

Jon Radus. Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. That same year, the Police Department started using a drone to monitor Downtown Fullerton and other areas.

In 2024, Fullerton police killed Alejandro Campos Rios outside a McDonalds. This prompted more protests.

This year (2025), Fullerton Police killed a young man named Pedro Garcia. Another homeless man, Jose Luis Naranjo Cortez, died in Lemon Park after an encounter with the police.

Although it may seem like there have been more police killings since 2020, this is more likely the result of recent California state laws that require mandatory public reporting of in-custody deaths. It is likely that, in previous decades, many in-custody deaths were not made known to the public.

The Fullerton Police Department does a fair amount of community outreach/public relations events like the annual National Night Out.

The local police union, the Fullerton Police Officers Association remains active in local politics, using their Political Action Committee to support and/or oppose candidates, often successfully. This has allowed the police budget to remain much more stable than other city employees who have had to weather much steeper cuts.

-

Fullerton in 1950

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library has microfilm from the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune newspaper stretching back to 1893. I am in the process of reading over the microfilm, year by year, to get a sense of what was happening in the town over the years, and creating a mini archive. Below are some news stories from 1950.

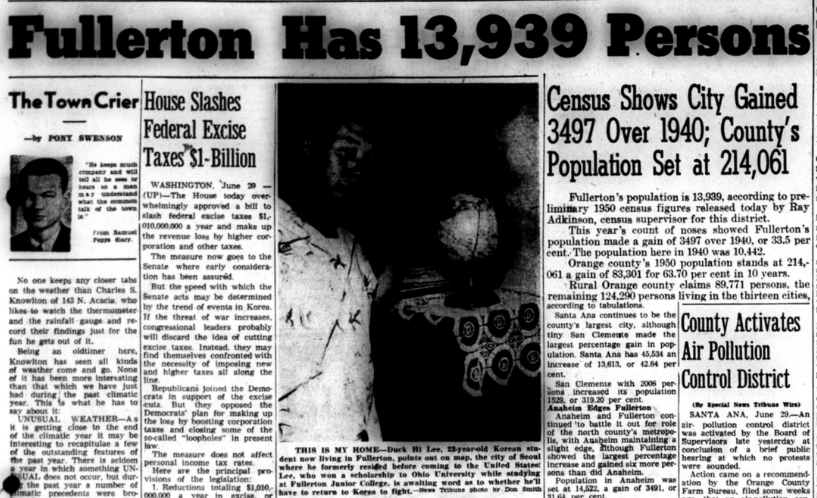

In 1950, Fullerton’s population was 13,939, and would continue to rise rapidly over the next two decades.

The Korean War

In international news, the Korean War was playing out as both a civil war between north and south, and as a proxy war between the communist east and the capitalist west in the context of the Cold War.

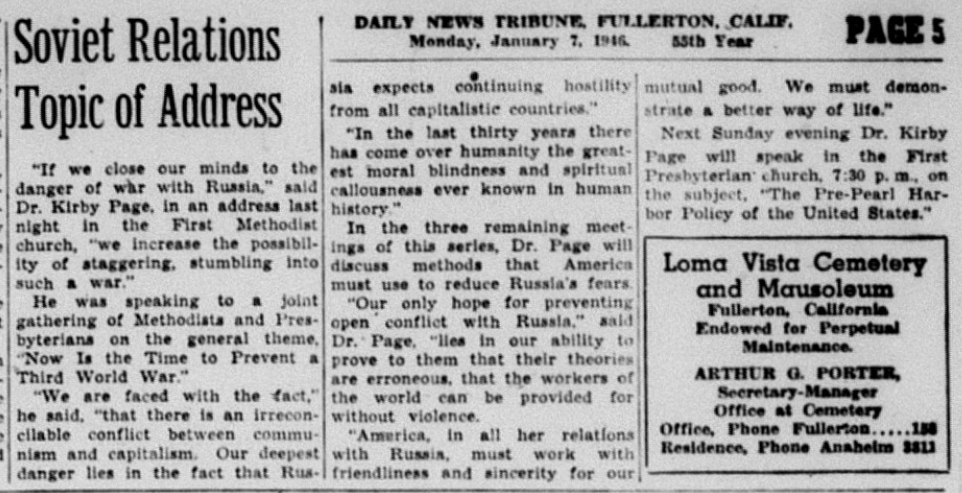

The Red Scare

On the homefront, Senator Joseph McCarthy was terrorizing American liberals and progressives by accusing many people of being communists, usually on the flimsiest of evidence.

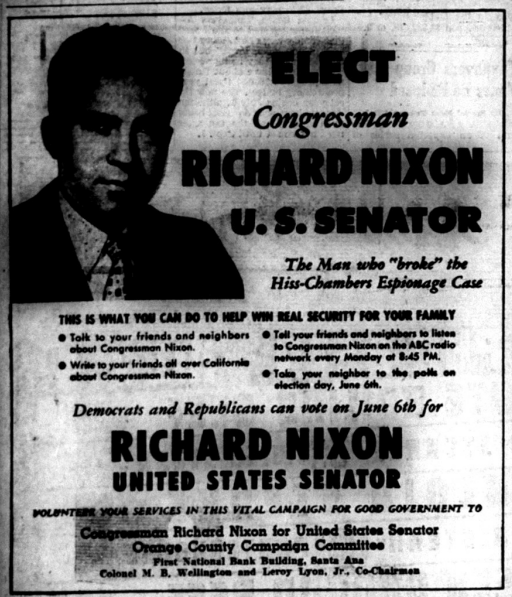

Richard Nixon (who was from Yorba Linda and had attended Fullerton Union High School) had been elected to Congress and was doing his part to fan the flames of the Red Scare. Fullerton in 1950 was a much more conservative place than it is today.

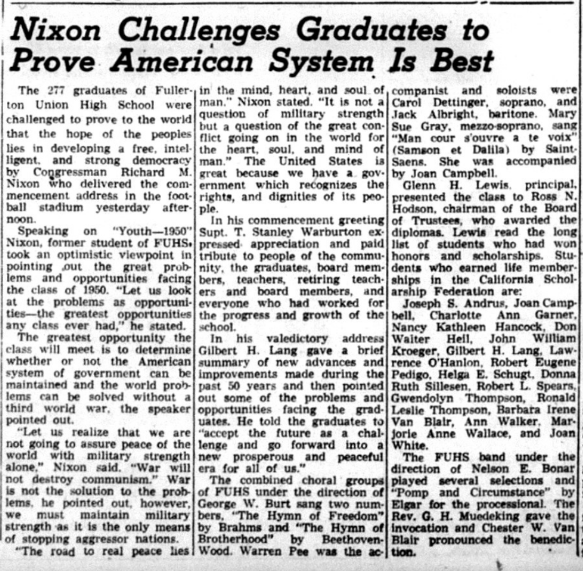

Being a local figure who was also running for Senate, Nixon made many appearances in Fullerton in 1950, including speaking at the FUHS commencement.

More Local Politics

In 1950, four men ran for two Fullerton City Council seats. They were:

Irvin “Ernie” Chapman, wealthy rancher, son of Fullerton’s first mayor/Valencia orange king Charles C. Chapman.

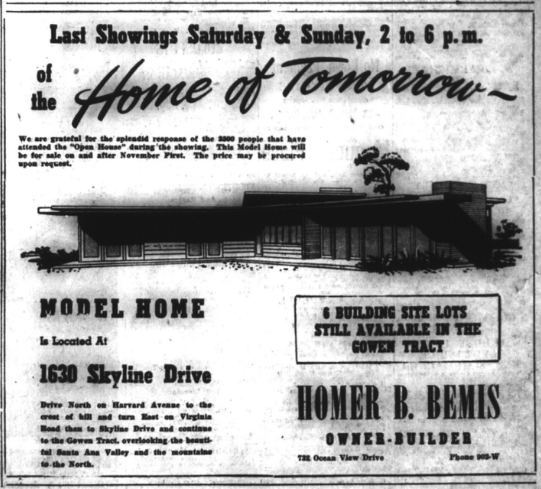

Homer Bemis, a general contractor.

Kermit Wood. Not sure what he did for a living, but he was likely a business owner and he ran on a platform of opposing a new business license ordinance.

Jack Adams, a former public relations man for Lockheed Martin, who also opposed the business license ordinance.

Ultimately, Adams and Wood upset the incumbents Chapman and Bemis–likely because of their opposition to the business license ordinance.

Thomas Eadington, fruit grower, was named Mayor.

Fires!

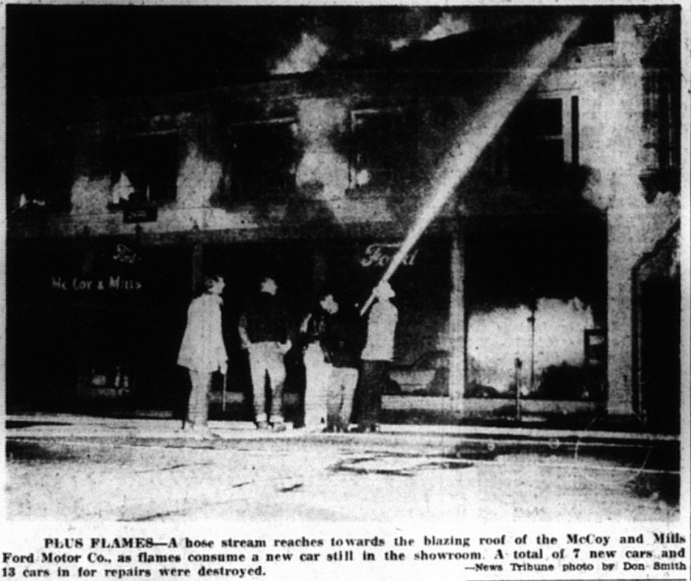

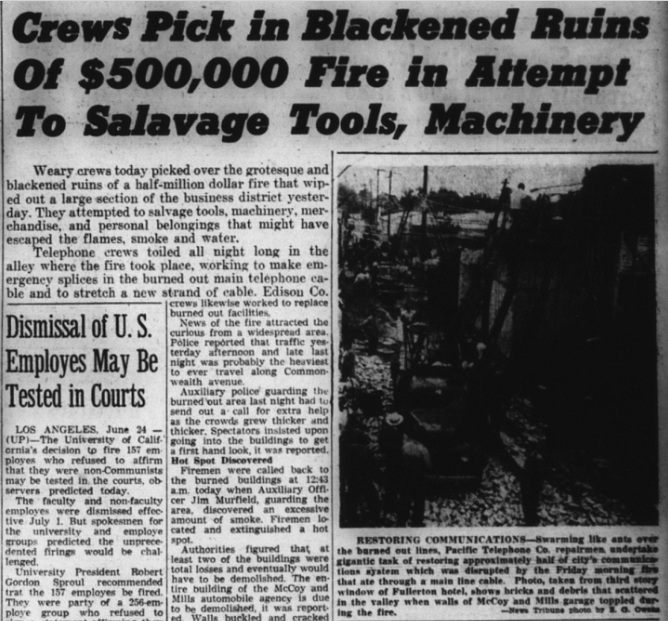

Probably the biggest and most tragic news story of 1950 was a massive fire that destroyed three major buildings downtown in the 100 block of West Commonwealth–the McCoy Mills Ford Agency, Pacific Citrus Products (famous for making Hawaiian Punch), and the old Fullerton Hotel. The damage was estimated at $500,000. Only one person was injured.

“An early morning fire, believed to be the worst in the history of the city, and probably the worst in Northern Orange County, totally destroyed an automobile agency, a citrus products plant, a 58-room hotel, and damaged a hardware store,” the News-Tribune reported.

It was believed the fire began at the Ford Agency before spreading to Pacific Citrus Products.

“The juice plant went up in a hurry as citrus oils and alcohol caught fire and an early morning breeze fanned the flames,” the News-Tribune reported. “As the citrus plant burned and bottles and cans exploded, syrup concentrate ran ankle deep in the gutters. The smell of scorched syrup filled the air.”

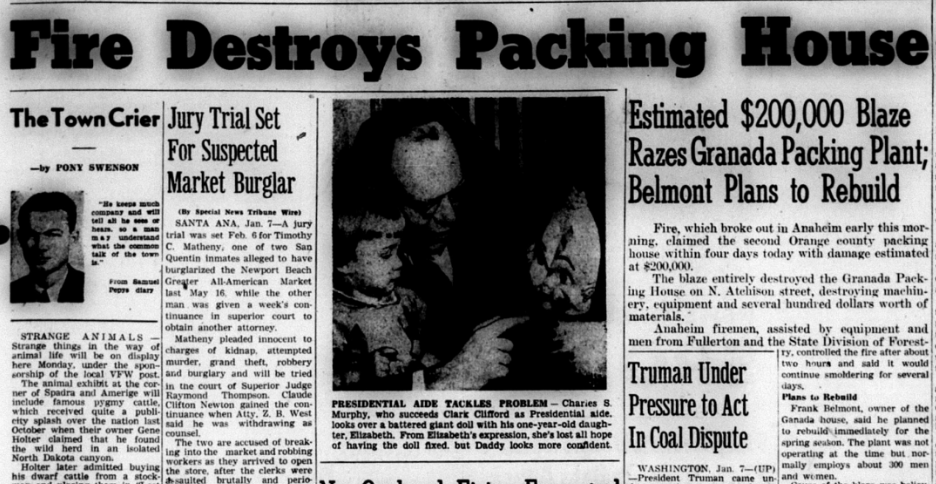

This was not the only fire in 1950. Another one destroyed a packing house.

Can a House be Built in Three Days?

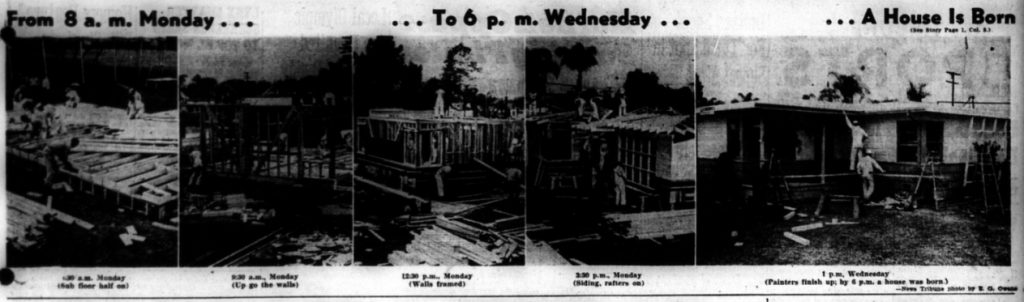

Fullerton continued to experience rapid growth, as many new housing subdivisions provided affordable homes. To demonstrate to the world that Fullerton was growing fast, local developers the Jewett Brothers hosted a big PR event in which workers built a whole house in three days.

A By-Product of Growth…Smog

Fullerton Goes to the Movies

For culture and entertainment, Fullertonians went to the Fox Theater, which celebrated its 25th anniversary in 1950.

The Fullerton News-Tribune includes an article about two men, Kenneth A. Rogers and Richard L. Martin, who worked at the Fox Theater since it opened. Rogers was superintendent of maintenance, Martin was the projectionist.

“Few, if any, of the large crowd that packed the theater on opening night know that a fire took place in the basement during the performance,” the News-Tribune reported. “Paint used used to color lights caught fire and the blaze set off the automatic sprinkling system. All available personnel were pressed into duty, bailing out the water which was seeping into the wardrobe trunks of a vaudeville troupe. C. Stanley Chapman, president of the company that operated the theater, Rogers recaslls, stood in two inches of water with the others trying to head off the flood.”

The article explains how, in the late 1920s, the theater became a favorite place for Hollywood previews.

“Among movie stars who attended previews of their pictures here were Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Sally Eilers, Harold Lloyd, Victor McLaglen, Buster Keaton, Colleen Moore, Janet Gaynor, Charles Farrell, and Edmund Lowe,” the News-Tribune reported.

The first movie shown at the theater was Tom Mix in “Dick Turpin,” (an English period piece) which was a flop.

Both Rogers and Martin got their jobs because they worked at the old Rialto Theater downtown. When Harry Wilbur left the Rialto to manage the new theater, he took the two men with him.

The other theater in town was the Wilshire Theater.

Cultural Appropriation

Fullerton Union High School hosted its annual “Pow Wow.”

Yass Queens!

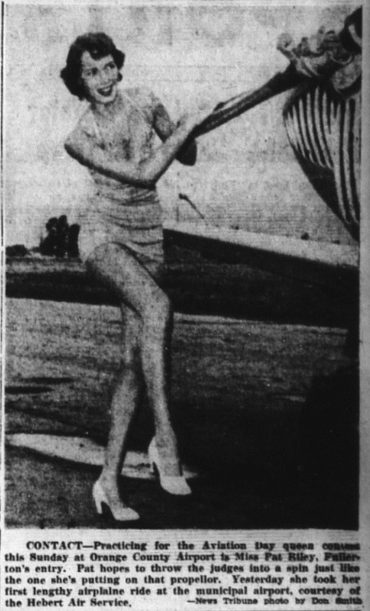

In the 1950s, Fullerton loved to crown queens for various public events.

The Midwest in SoCal

Fullerton hosted an “Arkansas Day” picnic on the Fourth of July that drew thousands.

New Schools

In education news, Golden Hills Elementary School was planned, to be built with bonds approved by the voters. Many new schools were built in the 1950s and 1960s as the area grew in population.

Fullerton put in a bid to be home to a new state college. Unfortunately, they lost out to Long Beach. It would be another decade before CSUF came to Fullerton.

Dr. H. Lynn Sheller succeeded William Boyce as head of Fullerton College.

The Big League Comes to Amerige Park

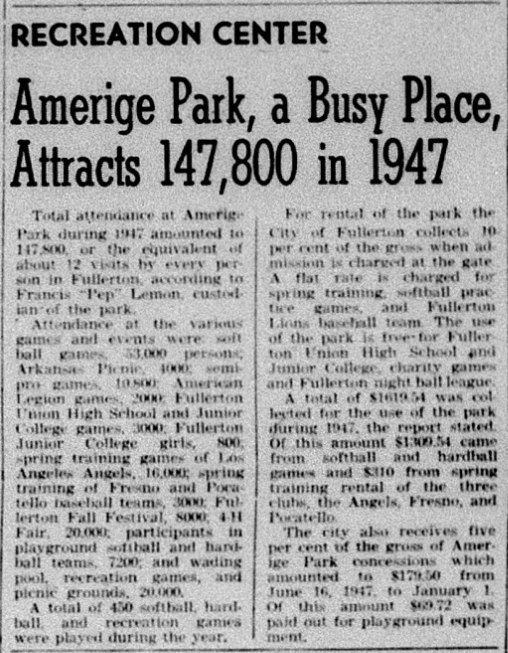

The Los Angeles Angels trained at Amerige Park in Fullerton.

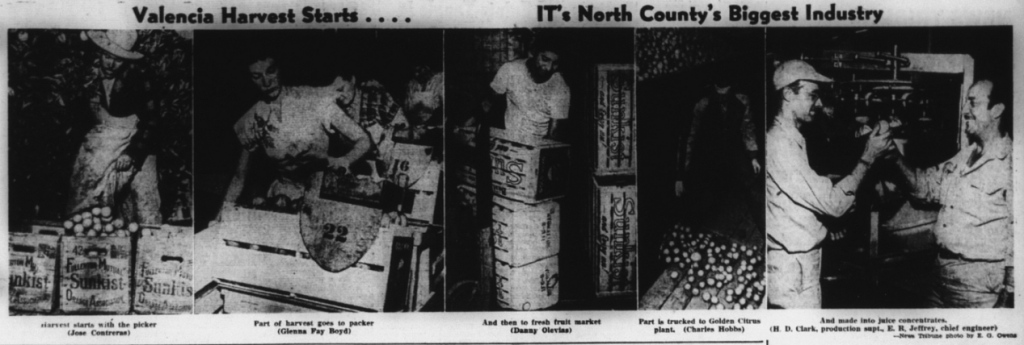

Citrus Industry

Although some orange groves were being plowed under for housing subdivisions, the citrus industry was still quite large in Fullerton and surrounding areas.

Stay tuned for top news stories from 1951!

-

Thomas K. Gowen: a life

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Last week, I was in the Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library browsing the shelves and came across a self-published autobiography of Thomas “Tommy” K. Gowen, who was an early rancher in Fullerton.

Thomas K. Gowen I had a personal connection to this person, as I grew up attending the First Evangelical Free Church of Fullerton, which Gowen also attended with his second wife Connie. As a young boy, I knew Connie Gowen–she was a well-loved elderly woman. Sadly, Tommy had died before I had the chance to meet him.

I read with great interest the story of Tommy’s life. Here is a summary of what I learned.

Gowen’s ancestors came to America in the 1550s from England, Scotland, and Wales, seeking religious freedom and to help establish a British colony.

His great grandfather James Gowen (“Uncle Jimmy”) was born in 1784. Uncle Jimmy settled near Lynchburg, Tennessee where started a farm. The adjoining farm was owned by none other than Davy Crockett!

Uncle Jimmy, being a Southern planter in the early 1800s, owned slaves. He fought in the War of 1812 under General Andrew Jackson in New Orleans.

Thomas K. Gowen was born in 1893 in Tennessee. Sadly, his father died of pneumonia four days before he was born, at age 30. Tommy grew up in a small farmhouse with his mother in Tennessee until he was 18. From age 12, he worked on local farms, including the Crockett farm.

Although he had limited schooling, “With the libraries of my two uncles at my disposal, I would sit up until midnight reading all kinds of books, learning more, I think, than the average college graduate,” Tommy writes

When Tommy was 20, he moved to Bakersfield and enrolled in Kern County High School and Junior College, living with his uncle Ben. He studied scientific farming.

“I got a job with the Kern Island Irrigation Company as a zanquero, delivering water to the Chinese gardeners, through the main ditches surrounding the city,” he writes.

When he arrived, most of the land was used for cattle grazing. It was here that he met and married Florence Burkett in 1915. The young couple briefly moved back to Tennessee, where their son Harlan was born.

After moving back to California, Tommy’s father-in-law, a relatively wealthy rancher, offered them a twenty acre orange grove in Fullerton.

In 1917, Tommy rode a horse-drawn wagon down to his new ranch in Fullerton. The family moved into a small farmhouse.

In 1919, Tommy took a job with the Union Oil Company, “working on the drilling derricks from midnight until 8am. In the daytime I would take care of sixty-five acres of oranges for my neighbors,” he writes. That year, their second son, Kenneth, was born.

It was while working for Union Oil that Tommy befriended Frank Nixon (Richard’s father): “In 1918 Frank Nixon (Dick’s father) and I became good friends. We went to work for the Union Oil Company of California and worked side by side for three years, then kept in contact with each other from time to time thereafter until he died in 1960.”

The family eventually moved into a house at 233 W. Santa Fe.

In 1921, he got into the fertilizer business. He traded his orange grove with Maxium Smith for a two-story house in Anaheim and 160 acres of desert land 12 miles west of Lancaster, where he planted barley.

In 1925 he bought a ten-acre orange grove on the south side of Valencia Dr, east of Brookhurst. Their son Kenneth, who had hemophilia, died of internal injuries after a kid pushed him off the bleachers at Ford School.

In 1928, they built a home at 1600 W. Valencia Dr. In 1932, Gowen was elected to Fullerton City Council. In 1936, he went to bat for his friend Walter Muckenthaler to be elected to city council.

“They said a Catholic had never served on the council and one could never be elected. I told them we had never had a Walter Muckenthaler run for the council, either,” he writes. “I went to twelve Protestant ministers in town and asked for their cooperation. They agreed to help. I think I oversold Walter; he got more votes than I!”

During Gowen and Muckenthaler’s tenure on City Council, they acquired WPA funds to build City Hall (now the police station). This was a controversial move, as other prominent businessmen wanted the city hall to be built on Spadra next to the California Hotel, instead of on Commonwealth, where it was built.

Gowen and Muckenthaler were also instrumental in getting more WPA funds to build the new library on Wilshire and Pomona, which is now the Fullerton Museum Center.

In the early 1930s, Tommy befriended Dr. John E. Brown, who was a leading evangelist of his day.

“In 1931 [Brown] sent his front man, Mr. C.A. Virgil, to Fullerton to build a temporary tabernacle on a vacant lot behind the Masonic Temple,” Gowen writes. “It had a capacity of 3,000 and was full every night for the three weeks he was there.”

Gowen was elected to be on the board of John Brown University to represent California. There he met Jesse H. Jones, who was chairman of the board. They enrolled Harlan at John Brown University in Arkansas.

Jones was a multi-millionaire who owned most of the skyscrapers in Houston, Fort Worth, and some in New York. He funded John Brown University. He was appointed by Herbert Hoover to be Chairman of the Reconstruction Finance Board, and was secretary of Commerce under Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Jones asked Gowen to help promote John Brown University, booking Dr. Brown to speak at 52 of the largest Rotary Clubs in the nation. There he met with many of the leading businessmen of America.

“Dr. Brown came to California and offered me the position of general manager of all the university’s holdings on the west coast: Brown Military Academy, the Brown School for Girls at Glendora, Radio Station KGER, twelve apartment complexes, and the Hotel Huntington in Long Beach,” Gowen writes.

In 1940, his wife Florence died.

Eventually, “Due to some of the financial practices of the administration of the school, Mr. Jones withdrew his support and I resigned from the organization, and reverted to being a farmer.”

In 1940, his fortunes considerably improved from when he first moved to Fullerton, Gowen “leased 110 acres of Valencia oranges in the Santa Fe Springs district from Standard Oil Company and others, and 700 acres of hay, grain and pasture land from Union Oil Company and Stern Realty Company from Fullerton to Brea, and from Brea to La Habra…With some partners, we leased 167 acres of Valencia oranges in front of Loma Vista Cemetery.”

After the death of his wife, he fell in love with his secretary Connie and they were married, they sold their home on West Valencia Drive and bought a two-story home on the southwest corner of Chapman and Balcom. They bought 160 acres on what is now Skyline Drive along with other property owners in what was known as the Skyline Syndicate. The area was subdivided into luxury homes. They moved into a home at 1701 Skyline Drive.

Connie Gowen. Now a wealthy rancher, Gowen befriended Walter Knott, who was a fellow advocate of Republican politicians.

In 1946, Tommy and Connie had their first child, Nancy. Their son, Tom Jr. was born in 1947. Sadly, Harlan (Tommy’s son from his first marriage) died in 1948. He was also a hemophiliac.

Gowen, now a gentleman rancher, part of the local landed gentry, acquired orange groves in Yuma, Arizona along with his friend California State Senator John Murdy.

In the early 1940s, he bought 165 purebred Hereford heifers from the Hearst ranch and ran them on land he rented north of Fullerton, and on his own land.

“Our whole family enjoyed having cattle running the two miles from what is now Longview Drive and Brea Boulevard to Rolling Hills and State College Blvd,” Gowen writes.

In 1947 he bought 47 acres of dead lemon trees, the piece that lies between Rolling Hills and Bastanchury Road, east of Brea Blvd. “We kept it about eight years and sold it to Ward and Harrington for a subdivision, helping the Fullerton Elementary School District obtain the site for Rolling Hills School,” Gowen writes.

He was instrumental in helping Chapman College (founded by local rancher Charles Chapman) move from Los Angeles to the site of the former Orange High School. Gowen served on the board of Chapman College until it became “too liberal.”

“Liberal professors refused to take the loyalty oath and the majority of the board let them get away with it,” so Gowen resigned.

In the 1950s, Gowen was the campaign manager for Republican John Murdy, who was elected to the California State Setate in 1956 and 1960.

“[Murdy] had 1,000 acres of land between Huntington Beach and Westminster on which he grew lima beans. Later on he became president of the California Lima Bean Growers Association, president of Hoag Memorial Hospital, a member of the Irvine Foundation Board, and many other worthwhile activities,” Gowen writes. “In 1952 some southern Orange County business men drafted John to run for the state senate…I was asked to be his campaign manager.”

Gowen was also instrumental in getting the state legislature to locate CSUF in Fullerton.

Gowen was an early supporter of Richard Nixon in his first presidential run in 1960. Tommy visited and had lunch with Richard Nixon at the capitol when he was vice president.

“During the presidential campaign in 1960, Mr. Knott hosted a big old fashioned Republican rally at the [Gowen] farm. The main speaker was Richard Nixon,” he writes.

In a letter to his daughter Nancy, Gowen describes Nixon’s famous “Southern strategy” to get conservative Southern Democrats to switch the Republican Party: “Dick had to have a vice president acceptable to Strom Thurman, the only man who could throw the south to the Republican party.”

Tommy visited and had lunch with Richard Nixon at the capitol when he was vice president.

Gowen wrote his memoir in 1975, shortly after the Watergate scandal and the resignation of Richard Nixon. Of this he wrote: “Having known the Nixon family personally for 56 years makes this tragedy a double shock for me.”

-

Fullerton in 1949

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library has microfilm from the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune newspaper stretching back to 1893. I am in the process of reading over the microfilm, year by year, to get a sense of what was happening in the town over the years, and creating a mini archive. Below are some news stories from 1949.

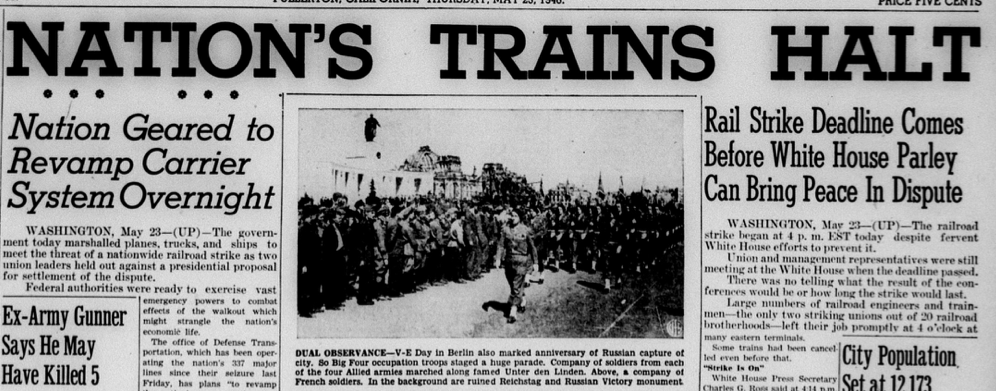

National and World News

In world news, the Russians tested their first atomic bomb–a pivotal event in the Cold War.

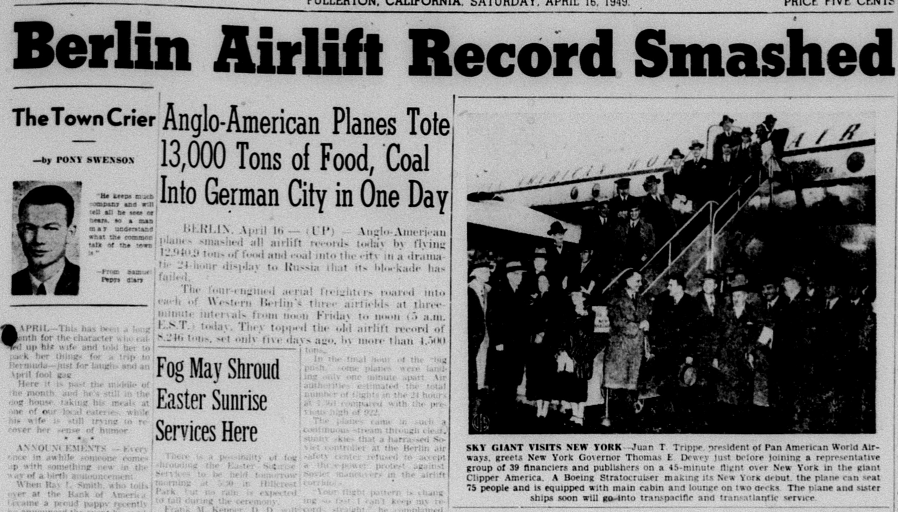

American planes were dropping food and aid into Russian-blockaded Berlin as part of the famous Berlin airlift.

The “Red Scare” was increasing in intensity, as famous Hollywood actors (including Frank Sinatra, Orson Welles, Charlie Chaplin, and Gregory Peck) were charged with being communists (they were not).

Although mass shootings are generally seen as a 21st century phenomenon, there was a mass shooting in Camden, New Jersey when a “Bible-carrying war veteran described as a near religious fanatic” shot and killed 12 people.

Local Pilots Set World Endurance Record

Perhaps the biggest local news event of 1949 was the flight endurance record set by local pilots Dick Reidel and Bill Barris who flew their plane the Sunkist Lady for 1008 hours.

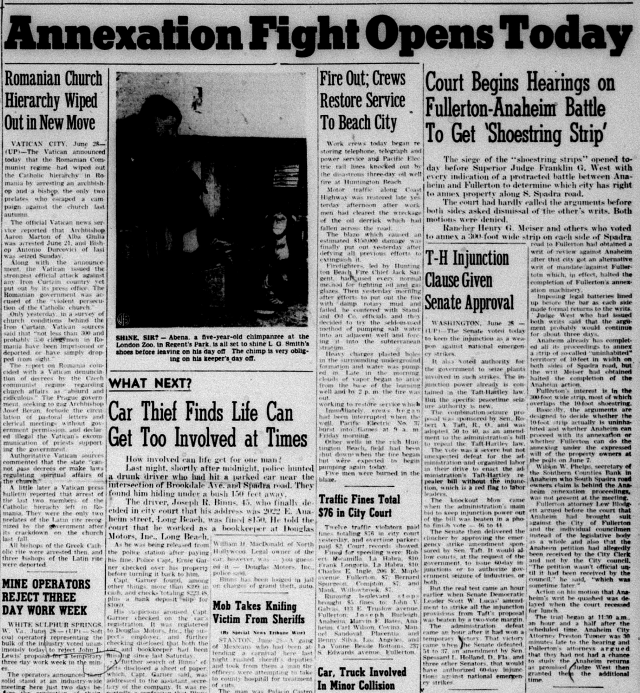

Annexation Fight with Anaheim

The second biggest local news story of 1949 was an annexation fight between Fullerton and Anaheim over a strip of “no man’s land” that once separated the two towns. At stake was future tax dollars from housing and industrial development. After much legal maneuvering, court fights, resident protests, and council meetings, Fullerton won the fight over the coveted land.

Housing

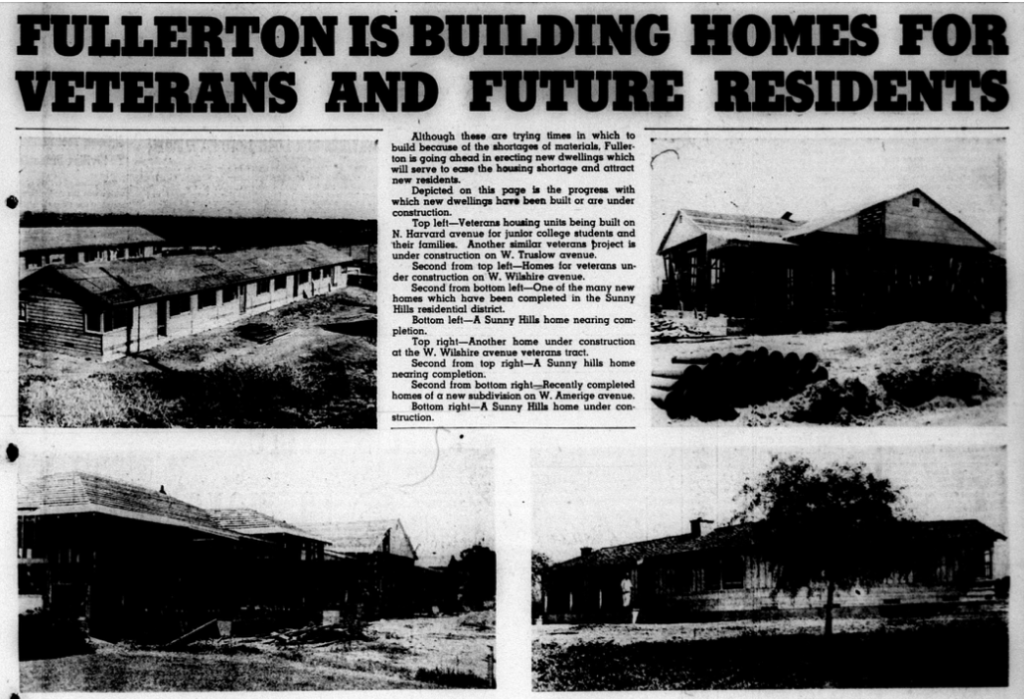

After World War II, Fullerton entered a period of rapid growth, as housing subdivisions replaced orange and walnut groves.

Another notable housing issue in 1949 was the end of wartime era rent controls, which had been put in place to protect renters during a period of a housing shortage. Landlords were keen to end rent control, and they were successful.

Education

To accommodate the population growth, new schools were constructed. In 1949, Fullerton opened Valencia Park school.

New schools and expansion of existing schools were often paid for with bonds.

Infrastructure

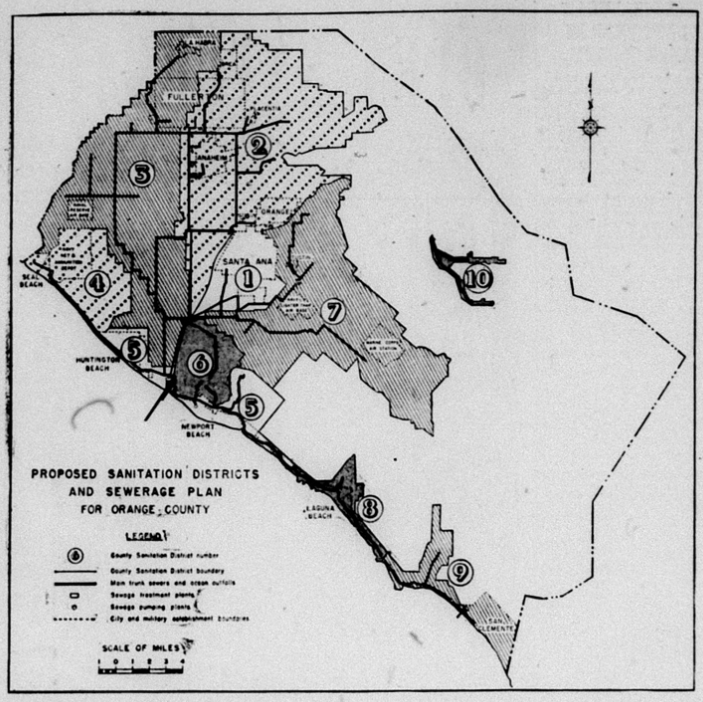

As Orange County grew, new infrastructure was needed, including an expanded sewer system, paid for with a bond measure.

The 1940s and 1950s saw the dawn of freeways in Southern California which required using eminent domain to acquire land from property owners.

Culture and Entertainment

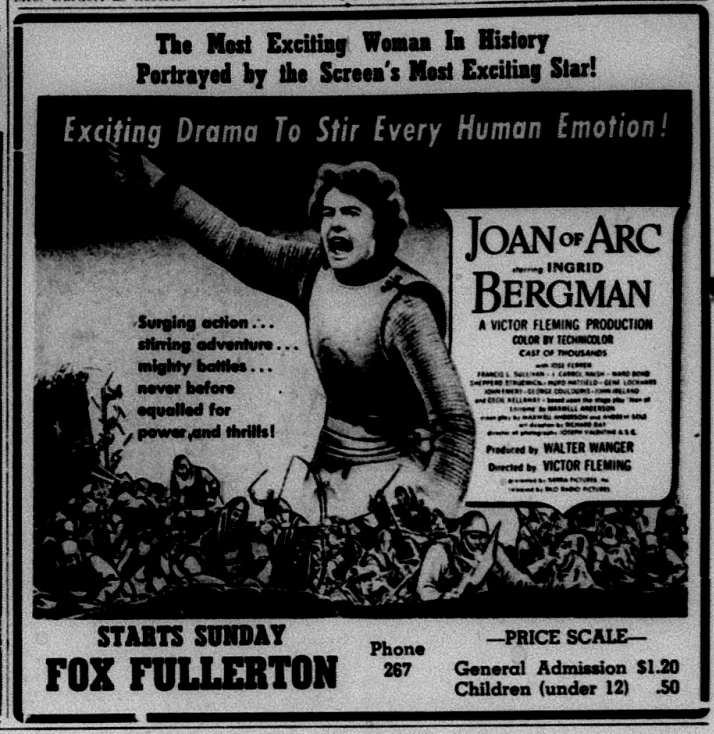

For culture and entertainment, Fullertonians went to see movies at the Fox Theater (which still exists) and the Wilshire Theater (which is now an apartment building).

Famous Broadway singer John Raitt, who was from Fullerton, returned to his hometown for a special concert.

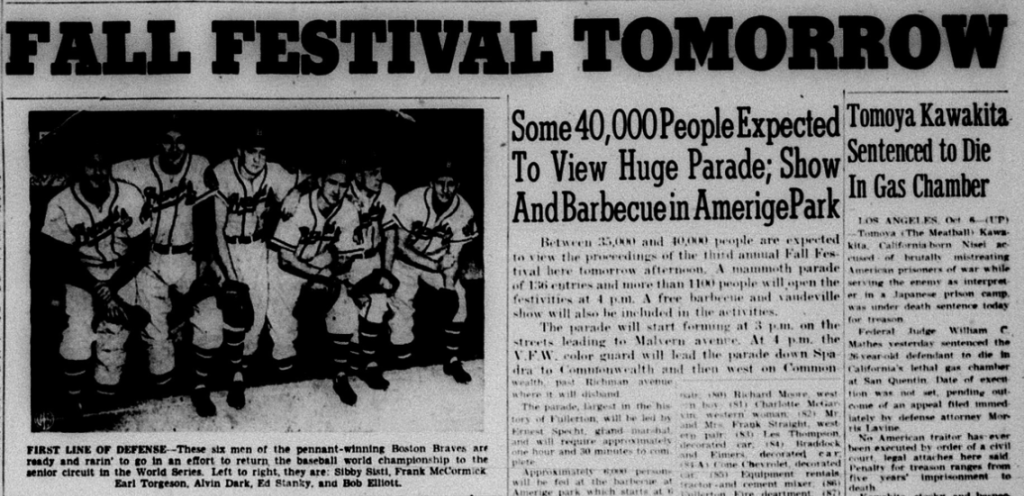

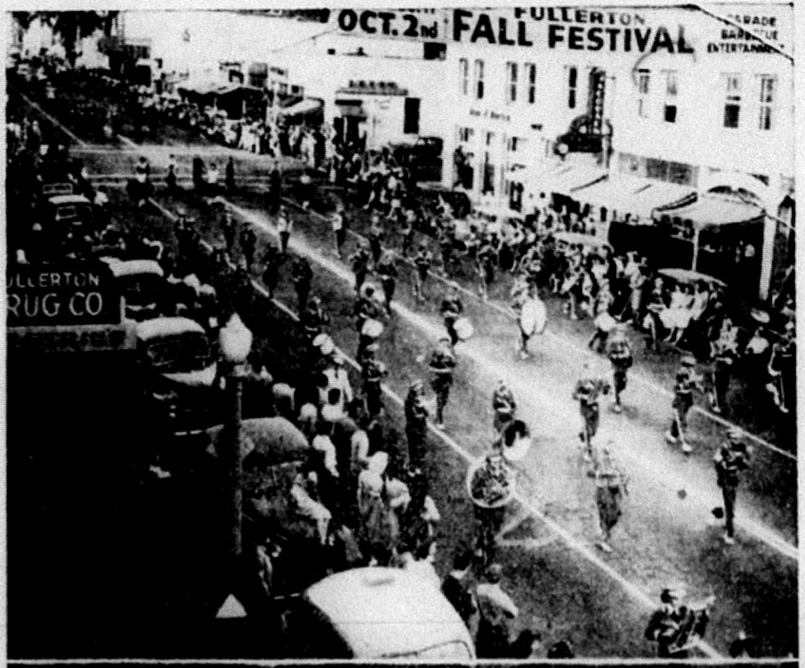

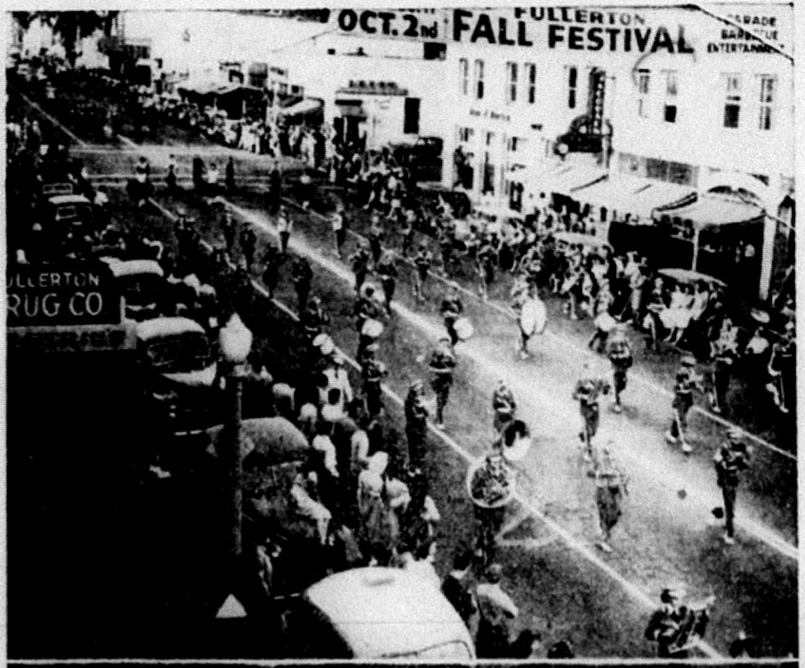

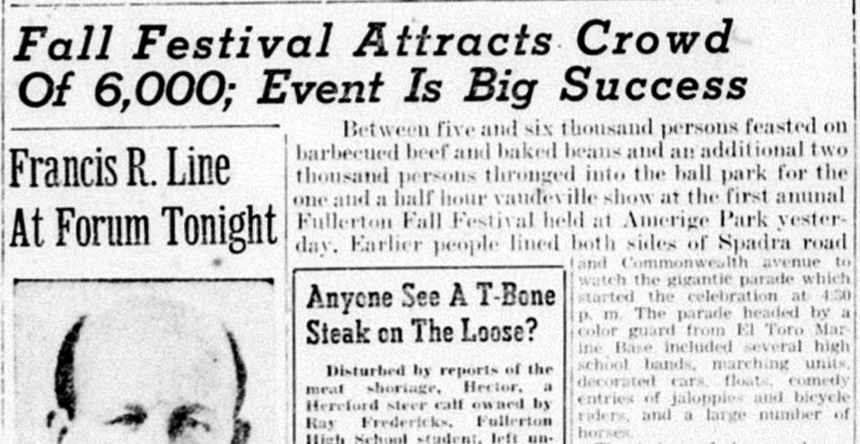

Fullerton hosted a Fall Festival that drew thousands.

Sports

In sports news, professional baseball teams would play games at Amerige Park.

Hometown hero Del Crandall entered the big leagues.

Business

The pages of the Fullerton News-Tribune contain advertisements for some notable local brands that started in Fullerton and went on to be big national brands, including Hawaiian Punch.

Social Life

There were numerous social clubs in Fullerton in 1949, some of which still exist.

Church was also an important part of community life.

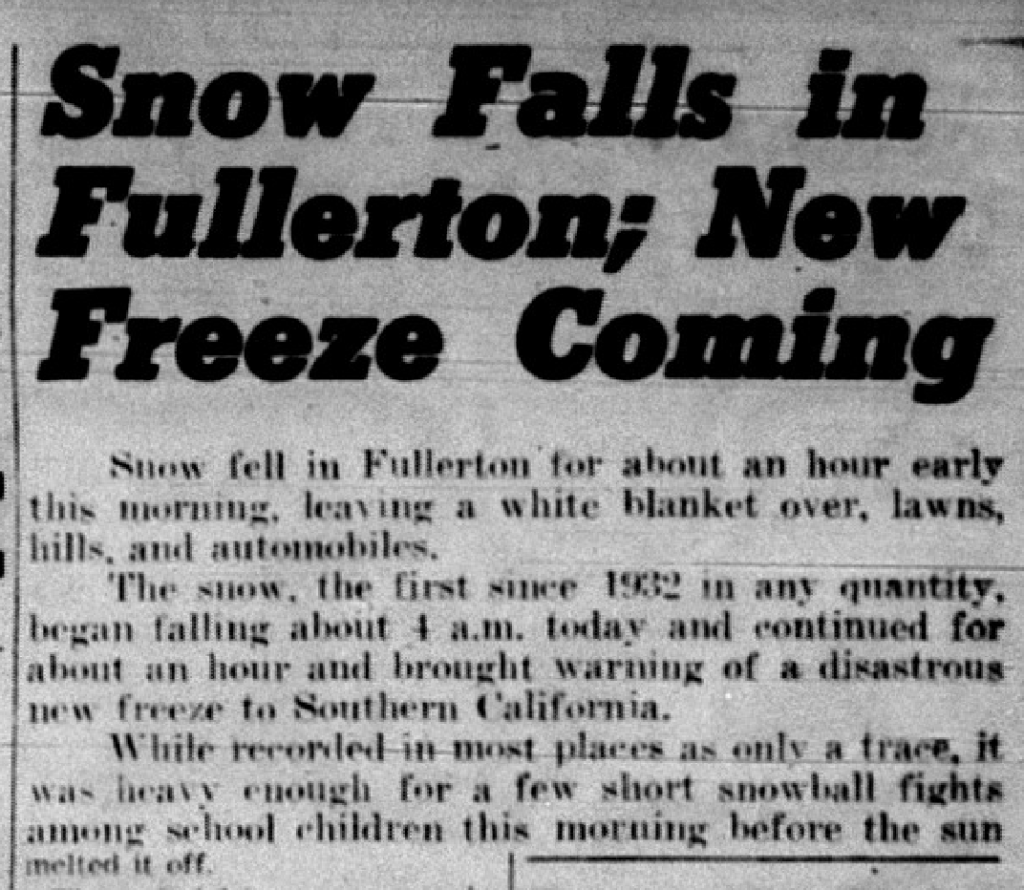

Snow Falls in Fullerton

A rare snowfall occurred in Fullerton in 1949.

Deaths

Beloved Fullerton College coach Arthur Nunn died.

Stay tuned for news stories from 1950!

-

Walter Muckenthaler: a life

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

This year, the Muckenthaler Cultural Center is celebrating its centennial. Exactly 100 years ago, in 1925, Walter and Adella Muckenthaler built their dream mansion atop a hill in north Fullerton. Forty years later, in 1965, the family gifted their stately home and the grounds around it to the city of Fullerton to be used as a Cultural Center. And since then, the Muckenthaler Cultural Center has been offering the public art exhibits, musical performances, classes, plays, and more.

As part of the centennial, the Electric Company Theater will be offering a unique immersive theatrical experience which utilizes the whole interior of the Muckenthaler Mansion and brings guests into the world of mid-1920s Fullerton, complete with real local historical figures, including Walter and Adella Muckenthaler.

Last week, the directors of the Electric Company Theater invited me to give a brief talk about what Fullerton was like in the mid-1920s, to get their patrons excited about the centennial production.

The whole experience has made me curious to learn more about the Muckenthaler family, and so I was delighted to discover in the local history room of the Fullerton Public Library a biography of Walter, which was written by Keith Terry. Because the family commissioned the biography, it is perhaps a bit of a hagiography. Nonetheless, it provides a fascinating window into this local family–their history and legacy.

I present here a book report on some things I learned from Walter’s biography.

The German Muggenthalers

Walter’s grandparents, Martin and Elizabeth Muggenthaler, immigrated from Germany to the United States in 1854. Their name was changed to Muckenthaler by a port official in Belgium.

“They must have heard of the tempting offers of land that American railroads promoted all over Europe at that time,” Terry writes. “Undoubtedly, Martin’s desire for cheap land in the American Midwest tugged at this imagination and motivated his immigration to the new frontier.”

After landing in New York, Martin and Elizabeth took a train west to Minnesota, where they acquired land and farmed for 17 years.

Walter’s father Albert was born in 1862, during the Civil War. He was Martin and Elizabeth’s sixth child.

After the Civil War, the US government opened up more lands out west for homesteaders. This was, of course, former Native American land. The Muckenthalers took their family to Kansas where they purchased 400 acres from a railroad company, near the famous Oregon Trail.

Martin and some fellow Germans laid out the town of Newbury, Kansas. He helped build the first schoolhouse, the Sacred Heart Chapel, and donated land for the town cemetery.

Albert Goes West

When he was 20 years old, Albert Muckenthaler wanted to try his fortune out west, so he and a friend traveled by train to the German town of Anaheim, California.

At that time, in the mid-1800s, Anaheim was a grape-growing area, so Albert and his friend worked in the vineyards, then as carpenters helping to expand the Planters Hotel.

Albert and his friend explored the California coast, from San Diego to San Francisco before returning to their families in Kansas.

Back in Kansas, Albert married Augusta Ebert in 1889. They purchased a farm in the town of Paxico, where they raised wheat, pigs, cattle, and chickens.

Albert and Augusta had a son, Walter Muckenthaler in 1894.

“Walter lived the rich, full life of a typical Kansas farm boy,” Terry writes.

Eventually, Albert felt the desire to return to Anaheim, so in 1909 the family headed west.

The Anaheim they encountered in 1909 was quite different from the one Albert had visited as a young man. A blight had wiped out the grape vineyards. Following a period of economic disaster, the local farms had shifted to growing walnuts and oranges.

Albert bought ten acres where he planted a small orange grove and built a large house for the family. In addition to growing oranges, they raised a small herd of cows and started selling milk and butter to the community.

Walter Comes of Age

Walter attended Anaheim high school on Lincoln Avenue. He took an interest in the arts and drama, acting in school plays.

Walter’s parents bought the Boston Bakery in downtown, where Walter worked while in school.

After graduation in 1916, Walter had saved enough money to attend the University of California at Berkeley, where he planned to study architecture. Unfortunately, he lacked the money to stay more than one year. So he returned to Anaheim just as the US was entering World War I.

He enlisted in the Navy, but was discharged because of a heart murmur. After working in the family bakery for a while, Walter got a job as a civil engineer for the Santa Fe Railroad.

Walter and Adella

In 1918, Walter married Adella Kraemer, whom he had known since high school.

Adella came from money. Her father, Samuel Kraemer, owned much of what is now Placentia. His vast lands included citrus and walnut groves, as well as cattle and oil wells. Her mother was Agelina Yorba whose grandfather Bernardo Yorba was a Spanish “don” whose large land grant included the present city of Yorba Linda.

“Both Walter and Adella enjoyed frequenting the popular night spots, cafes and restaurants where they always hoped to catch a glimpse of some famous silent film idol. They especially liked to go to Nat Goodwin’s Cafe on the Santa Monica Pier,” Terry writes. “On different occasions, Walter and Adella saw Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Herbert Marshall, the two Barrymore brothers, Gloria Swanson, Anita Stewart, the Talmade sisters, and many others.”

Walter and Adella moved into a small apartment in Fullerton.

Walter’s job as an engineer for the Santa Fe railroad kept him away from home for weeks at a time. So his wealthy and influential father-in-law Samuel Kraemer put in a good word with Fullerton’s city engineer Herman Hiltscher, and landed Walter a job as a city surveyor.

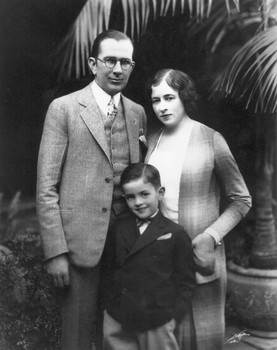

In 1922, Walter and Adella had their only child, Harold.

The young couple’s fortunes changed dramatically when Samuel Kraemer’s land yielded a number of oil gushers, which he had leased to Standard Oil.

“Samuel Kraemer leased out his mineral rights to Standard Oil of California, then watched in fascination the thousands of barrels of oil his land yielded up that first year,” Terry writes. “He decided to share his newly discovered wealth with all his children. Each one received interest in the oil leases and Walter and Adella began receiving regular royalties from their inherited leases.”

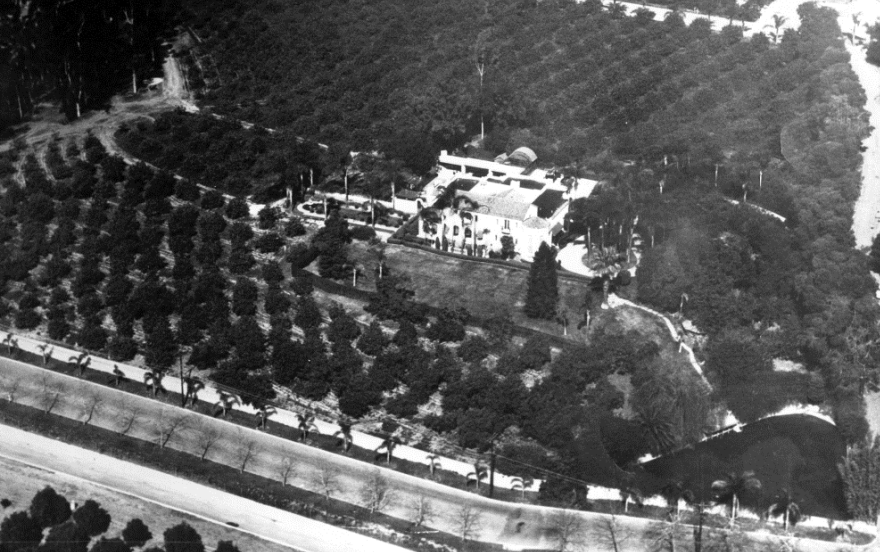

It was these oil royalties that provided the capital for Walter and Adella to purchase eighty acres of land along Euclid, between Commonwealth and Malvern. There they got into the Valencia orange business and it was there, atop a hill, that they built their stately mansion in 1925.

The Muckenthaler Home

Walter hired local architect Frank K. Benchley to design their stately home, built in the Mediterranean style. Benchley had designed a number of iconic Fullerton buildings, including the California Hotel (now the Villa Del Sol).\

The Muckenthaler mansion took six months to complete at a cost of $34,000 (which is approximately $630,000 in 2025 dollars, not enough to purchase a modest single family home today).

“Standing on the cast stone balcony off the upstairs bedroom, Walter and Adella could see, on a clear day, all the way to Catalina island,” Terry writes.

Walter’s friend Clark B. Lutschg designed the architectural landscaping around the mansion.

Fullerton City Councilman

At the urging of his fellow orange rancher friend Tommy Gowen, Walter ran for city council in 1936.

At first, the local elite were skeptical of Walter because he was Catholic in a (mostly) Protestant town. But Gowen went to bat for Walter and he was the first catholic elected to Fullerton city council.

“At that time, council met in the upstairs room of the makeshift city hall–located just off the main street behind the California Hotel on Wilshire,” Terry writes. “The building served as a combination police station, fire house, city clerk’s office and water works office.”

It was during Walter’s tenure on City Coucil that the City obtained WPA (New Deal) funds to build the City Hall on Highland and Commonwealth avenues (which is now the police station), built in 1940.

The 1938 flood hit Fullerton during Walter’s tenure on council.

“The small dams located at the top of Santa Ana Canyon gave and disaster struck with a mighty torrent of water that rushed through the mouth of the canyon and spread out over the towns and farms of Orange County sweeping everything in its wake,” Terry writes. “At Atwood, located in present day Placentia, the little homes were lifted off their foundations and carried downstream like small boats. In Fullerton the dams burst making Harbor into an asphalt riverbed.”

After the flood “Walter was determined that Fullerton should never have to suffer again the terrible deluge it had just experienced.”

Walter helped obtain federal funding to create a cement lined barranca and construct a new dam above Harbor.

The War Years

In 1942, America entered World War II. That year, Walter decided not to run again for city council, and instead got himself appointed to the Planning Commission.

In the late 1930s Walter hired a Japanese gardener. In 1942, this gardener was arrested by federal agents who claimed he was a foreign agent and taken to an internment camp.

Harold Muckenthaler joined the Navy and served during the War.

After the war, Harold and his wife Shirley had two daughters.

In the 1940s, “Walter had expanded his interests to include citrus farms in both Ventura and Home Gardens near Corona,” Terry writes. “He bought a four story business building on Fourth and Broadway in Santa Ana.”

The Declining Years

In the early 50s, Walter’s health began to decline, and he was diagnosed with leukemia. He transferred most of his affairs to his son Harold.

“There were the numerous boards of director to transfer and the ranches and holdings Walter had acquired through the years,” Terry writes. “Harold and been well trained by his father and knew many of the prominent men who served with his father on large corporations.”

During the 1950s, according to Harvard historian Lisa McGirr, the Muckenthaler family were associated with the right wing John Birch Society.

Walter died in 1958. Seven years later, Adella and Harold would donate the Mucketnaler mansion to the city of Fullerton to be used as a cultural center.

-

Fullerton in 1948

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library has microfilm from the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune newspaper stretching back to 1893. I am in the process of reading over the microfilm, year by year, to get a sense of what was happening in the town over the years, and creating a mini archive. Below are some news stories from 1948.

Growth

In 1948 Fullerton had a population of 13,235, and its population would continue to grow in the coming decades.

Following World War II, Fullerton experienced a period of rapid growth, as new housing subdivisions, schools, shopping centers, and industrial parks replaced orange groves.

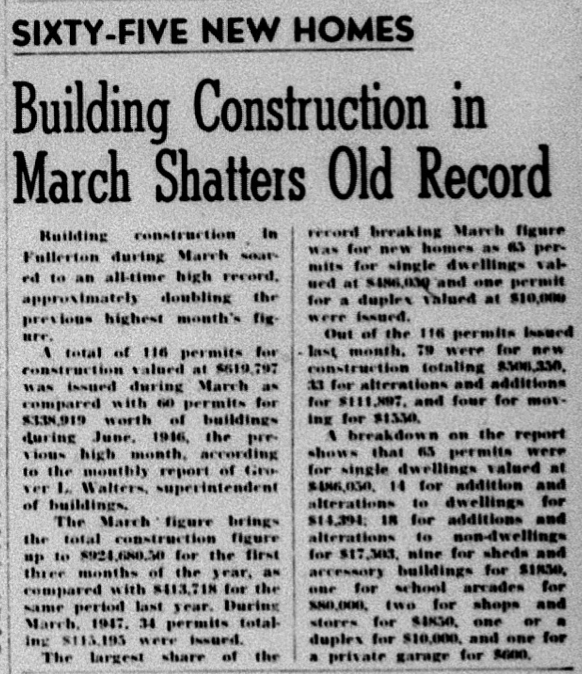

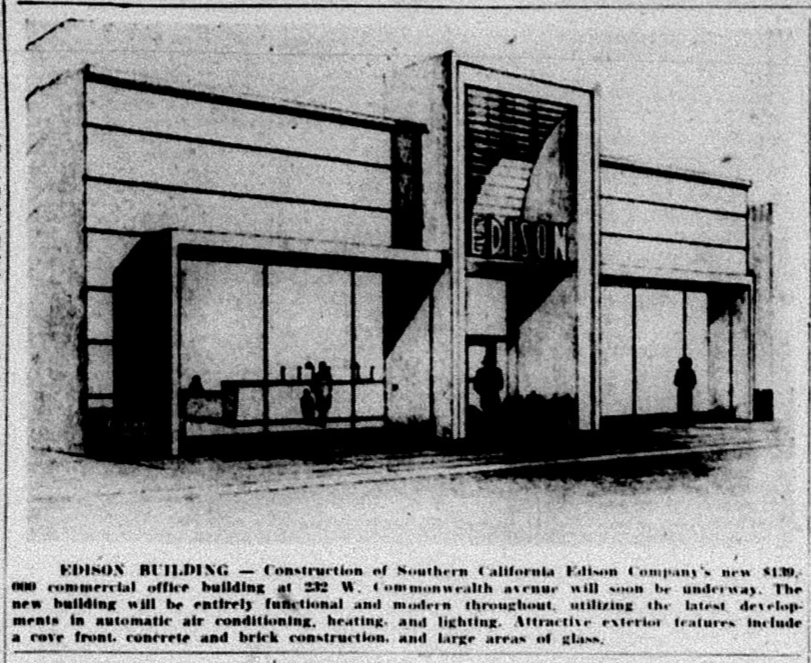

In addition to new housing subdivisions, new buildings popped up as well.

To accommodate the population influx, a new school (Valencia Park) was planned. This would be the first of many new schools built after World War II.

To accommodate the increased population, and traffic, freeways were constructed.

Businesses

Here are some prominent businesses of Fullerton in 1948:

Hawaiian Punch was created in Fullerton!

Norton Simon’s Hunt Foods was a major local employer.

A fast food entrepreneur named Carl Karcher established his first permanent restaurant between Fullerton and Anaheim:

Annexation Fight with Anaheim

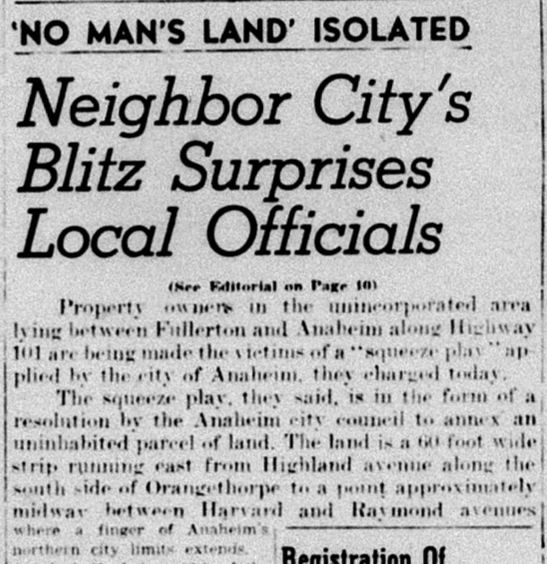

As both Fullerton and Anaheim grew, annexation fights began between the two cities to incorporate land between the two cities. The first salvo of this fight occurred when Anaheim city officials convened a special Saturday session to annex a 60-foot strip close to the south border of Fullerton.

In an editorial called “Skulduggery in Anaheim,” the Fullerton News-Tribune reported:

“When a city council finds it necessary to meet in special session on a Saturday, it is either a case of dire emergency or some kind of skulduggery. Anaheim’s city council met in special session last Saturday.

The business before the council consisted of passing a resolution to annex a strip of land 60 feet wide along the south side of Orangethorpe from Highland avenue to a point approximately midway between Harvard [Lemon] and Raymond avenue where a finger of Anaheim’s north city limits extends.

That a city council would hold a special session to pass a resolution to annex a piece of land which seemingly has no immediate bearing o the welfare of Anaheim, such action can hardly be called a “dire emergency.” That leaves only one category under which it can fall: skulduggery!

One need only to study a few of the facts behind the action by the Anaheim council to understand why it went to the trouble of a special Saturday session.

The area along Highway 101 between Fullerton and Anaheim is unincorporated. Its growth and development in recent years have made it obvious that it will some day become a part of some municipality, which would mean either Fullerton or Anaheim. An area of this nature needs the advantages that any city offers: fire and police protection, trash and garbage collection, sewer and water facilities.

Sentiment for becoming part of a municipality has run high in recent years, and especially more since a Metropolitan Water District edict forbids any new users outside the city limits. This ruling checks and futurity development of property in this unincorporated area until it becomes. Part of one city or another.

On September 11 of this year property owners took legal steps for becoming part of Fullerton by filing a notice of intention to circulate a petition relative to annexation of the territory. With enough signatures to the petition the matter could be put to the vote of the people of the area concerned. The people could choose between remaining unincorporated (with a chance of later joining Anaheim) or joining with Fullerton. Property owners who are working to initiate the petition say that the vote would be overwhelmingly for Fullerton.

It is no secret that Anaheim has coveted this territory. It would stand to lose by letting the people express their desires at the ballot box. With the handwriting on the wall, there was only one course for Anaheim to follow: throw up a legal roadblock between the territory and the Fullerton city limits by annexing a piece of land between the two.

It is reminiscent of Hitler’s tactics in instituting his famous “JA” and “neon” ballots during European plebiscites.

Fullerton officials sought to head-off this land-grab by meeting with Anaheim officials, but their efforts came to naught.

It would fall to property owners to sue Anaheim over the annexation move, which they won. But the fight was not over.

Politics

Harry S. Truman, a Democrat, won the 1948 presidential election.

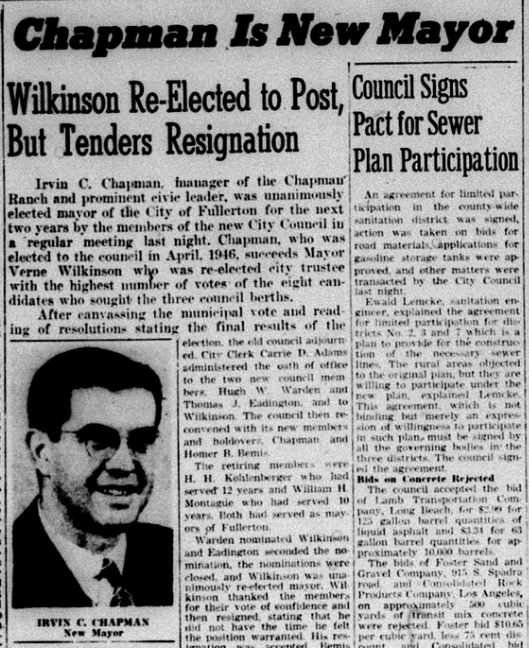

Locally, Verne Wilkinson, Hugh Warden, and Thomas Eadington were elected to City Council.

Irvin “Ernie” Chapman, son of Fullerton’s first mayor Charles C. Chapman, was chosen as mayor.

Here are some other local officials who were elected:

A young Republican congressman from Yorba Linda named Richard Nixon (who attended Fullerton High School) was making a name for himself by fanning the flames of anti-communism.

“Disclosure of Communist infiltration in high places in the administration in Washington will be made by Congressman Richard M. Nixon, “working” member of the Thomas Committee which unearthed the national intrigue, at a dinner meeting Oct. 13 at 7pm in Santa Ana Masonic Temple,” the News-Tribune reported. “The committee will resume hearings in Washington later and its probe will be largely on the findings Nixon makes. It will mark the first public appearance at which Capt. Nixon has talked in Orange County, although he was guest Oct. 1 of the Chamber of Commerce at Yorba Linda, his home town, where he attended school as a boy. The meeting is to be under the sponsorship of the Orange County Republican Assembly, now headed by Roscoe G. Hewitt of Santa Ana, who recently succeeded Hilmer Lodge of Fullerton as president.”

Agriculture & Immigration

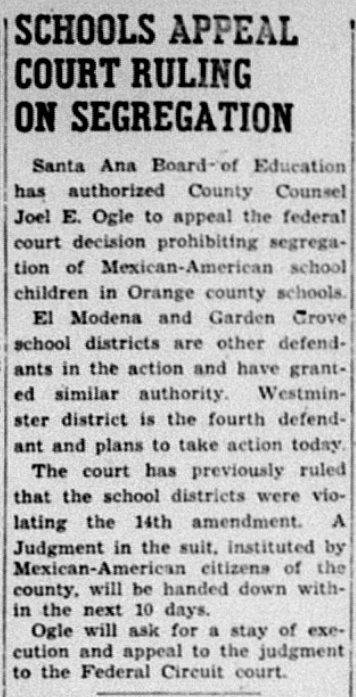

Although Fullerton was in the process of transformation from agriculture to housing and industry, the citrus industry was still alive and well in 1948.

Most of the citrus workers were Mexican, many of whom were recruited to work in local fields by the Bracero Program. The large presence of of Mexicans in Fullerton was sometimes protested by white residents.

During the Bracero Program, some citrus growers sought to supplement their workforce with undocumented immigrants.

Sports

In sports news, local professional and amateur baseball teams played games at Amerige Park.

Culture and Entertainment

For culture and entertainment, Fullertonians went to movies at the Fox Theater and the newly-built Wilshire Theater.

Fullerton also hosted a Fall Festival that drew thousands.

War Memorial

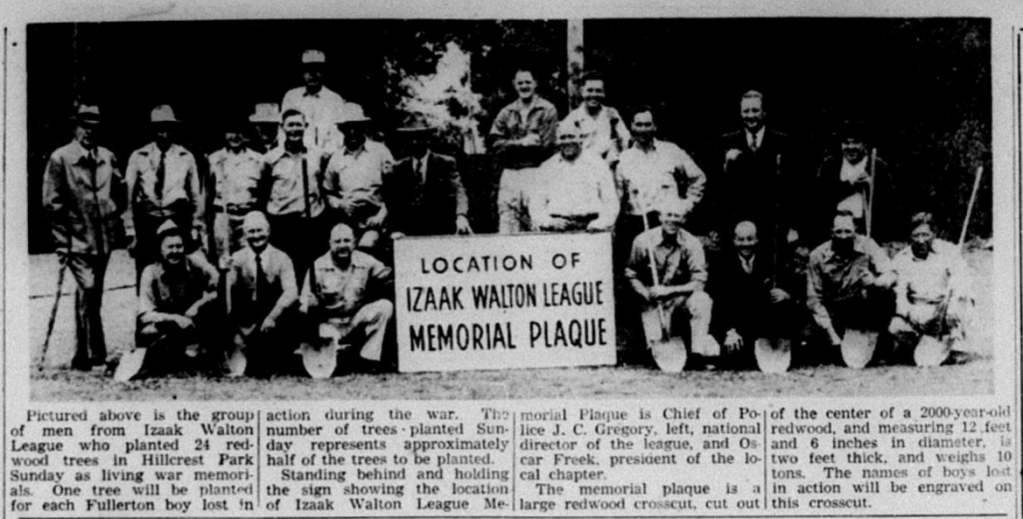

After voting down a bond measure to build a large War Memorial community center next to Amerige Park, Fullertonians decided to honor the war dead in a more modest gesture, a memorial listing the 54 names of those who died at Hillcrest Park, inscribed on a huge sequoia tree cross section.

Crime

In crime news, a gunman was arrested following a holdup downtown.

And a “new” drug called Marijuana (aka cannabis) was becoming popular.

Talk of the Town

The Fullerton News-Tribune had a section called “Talk of the Town” in which local residents were asked to give their opinions on a variety of social issues. Here is a sampling:

Celebrating European Conquest

An annual event celebrating the expedition of Gaspar de Portola was held annually in Southern California.

“Entry of the first white man, Gaspar de Portola, into this area will be portrayed at a joint Anaheim-Fullerton ceremony to welcome 54 horsemen who are riding from San Diego to San Francisco along the same trail the famous Spaniard followed in 1760,” the News-Tribune reported.

Deaths

The following people died in 1948:

Flora Starbuck, wife of pioneer druggist William Starbuck.

Roy Schumacher, the first child to be born in Fullerton.

Dr. George C. Clark, Fullerton’s first doctor.

William Hale, early City Councilmember.

Stay tuned for more stories from 1949!

-

Fullerton in 1947

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library has microfilm from the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune newspaper stretching back to 1893. I am in the process of reading over the microfilm, year by year, to get a sense of what was happening in the town over the years, and creating a mini archive. Below are some news stories from 1947.

In 1947, Fullerton celebrated its 60th anniversary.

But before getting into what was happening locally, here’s a bit of context about what was happening in the world in 1947, with clippings from the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune, and how these larger events trickled down to affect things here.

Rebuilding Europe

During World War II, much of Europe had been devastated by bombing and other forms of death and destruction. In 1947, the US was developing aid plans for European countries that would ultimately culminate in the 1948 Marshall Plan.

While beneficial to Europe, the Marshall Plan also helped to establish US economic and military hegemony after the war—with lots of US. bases around the world and trade deals that were favorable to the US. I’m currently reading an excellent book called How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater Untied States by Daniel Immerwahr, which goes into this in greater detail.

The increasingly globalized trade and US military presence after World War II would benefit a number of local companies, including Hughes Aircraft (which opened a plant in Fullerton in 1957 and was for a time the city’s largest employer).

The Military-Industrial Complex

World War II saw a massive mobilization and expansion of the American war industry. Thousands and thousands of airplanes, bombs, jeeps, tanks, ships, and more were built by private, for-profit companies, and paid for with American tax dollars. When the war ended, it seemed like the days of huge government contracts were over.

Thankfully, the escalating Cold War would allow these contracts to continue.

Industrialists Howard Hughes and Henry Kaiser were accused of using questionable means to acquire large government contracts.

This cozy relationship between war profiteers and the government would be given a name by outgoing president Dwight D. Eisenhower…the military-industrial complex. In his farewell address, he said:

“We have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. . . . This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. . . .Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. . . . In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”

Red Scare

During World War II, Russia was a US ally. Without Stalin’s Red Army, Hitler might not have been defeated. Many more Russian troops died fighting Nazis on the eastern front than American troops on the western front.

After the war, relations between communist Russia and capitalist United States began to sour. The countries clashed in the United Nations, and on various foreign policy matters. These clashes would ultimately lead to the Cold War and a sometimes paranoid “anti-Communist” push both within the United States and in US foreign policy. This would culminate in the Truman Doctrine abroad and the Red Scare at home.

One of the folks who really fanned the anti-communist flames was FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

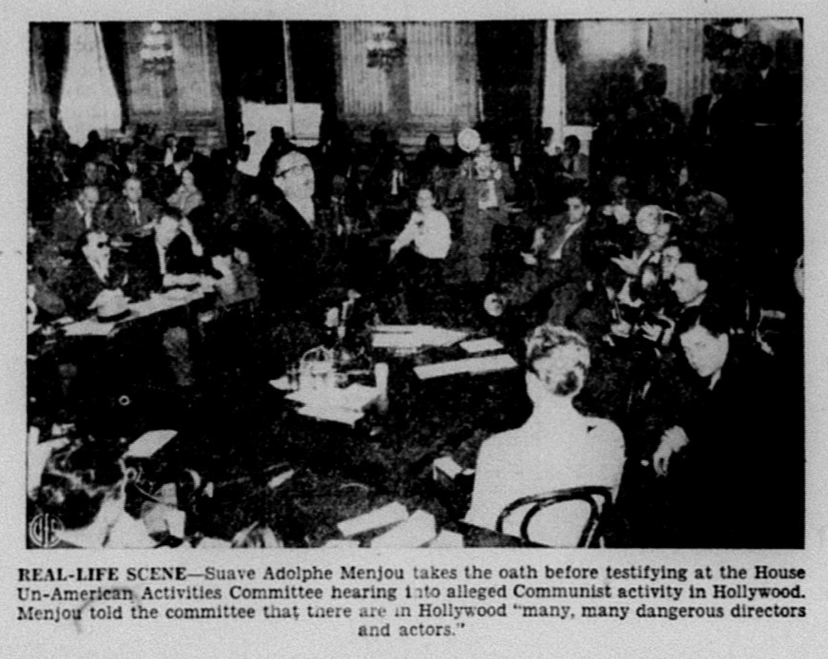

Closer to home, there were hearings regarding so-called communists in Hollywood.

Fullertonians at this time, being a pretty conservative group, tended to fear communists. Here’s a little editorial by the editor of the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune published in 1947.

Also in the News…Palestine

After the war, nationalist movements in former European colonies led to independence in places like India. In 1947, the country that would become Israel was called Palestine and it was controlled by Britain in a quasi-colonial “mandate” system. At this time, the Zionist (nationalist) movement was in full force, trying to establish the state of Israel, which would be accomplished in 1948, at great cost to Arab Palestinians. In 1947, the British left the Palestine matter to the newly-formed United Nations, which created a Special Committee on Palestine.

“In August 1947 the committee issued both a majority and a minority report. The majority report called for the termination of the mandate and the partition of Palestine between Arab and Jewish communities with the stipulation that the two communities be united in an economic union,” James L. Gelvin writes in The Israel Palestine Conflict: a History.

The US supported the partition plan, much to the chagrin of Palestinians, who were not keen on losing big swaths of their country.

War was on the horizon. Stay tuned for more on this in my 1948 post. In the meantime, check out my brief history of the Israel-Palestine conflict HERE.

Housing

I recently posted a report on the book Fullerton: The Boom Years, which is about the City’s extraordinary growth after World War II. That book details how, after the war, orange groves were replaced by new housing subdivisions, schools, shopping centers, and industry.

Culture and Entertainment

For culture and entertainment, Fullertonians went to movies at the Fox Theater.

And a new theater was built—the Wilshire Theater, which has its own interesting history. This eventually was replaced by apartments.

Fullerton celebrated a Fall Festival, which drew thousands.

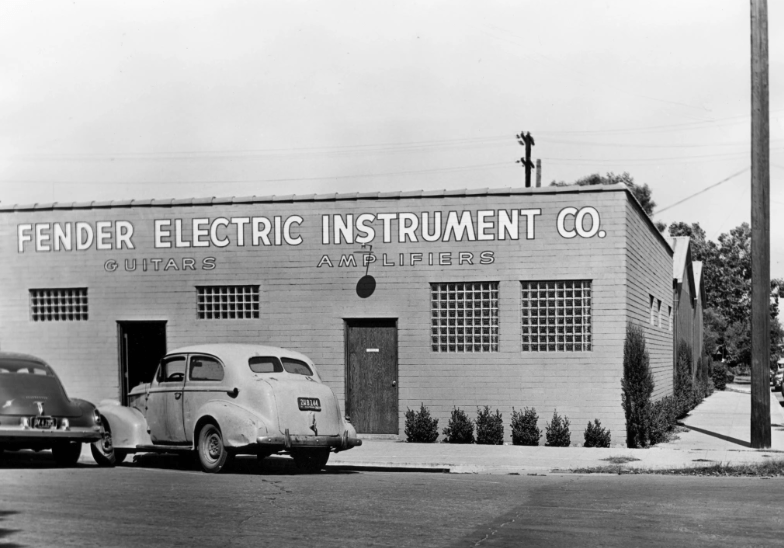

Leo Fender, who had a popular radio repair shop in town, was beginning to design and manufacture electric Fender guitars, although his ads in the local newspaper focused on radios and records.

Sports

In the 1940s, Major League Baseball teams would sometimes play games at Amerige Park in Fullerton, drawing huge crowds.

Infrastructure

As Southern California grew after the War, new infrastructure was needed, including increased sewer capacity.

And something new was born after the War which would become an iconic part of the Southern California landscape—freeways!

Technological advancement saw old “crank” telephones replaced by dial phones.

Politics

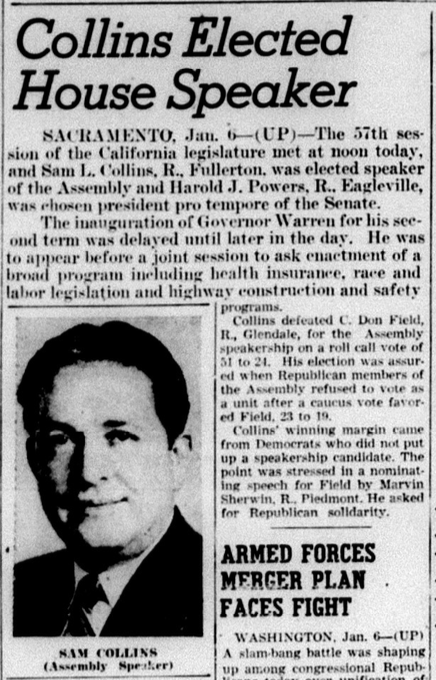

Sam Collins (from Fullerton) was chosen to be Speaker of the California State Assembly. Collins was a very influential politician in Sacramento. He remains the longest-serving Republican Speaker in history.

Fullerton Gets National Guard Armory

A National Guard Armory was established in Fullerton in 1947. Eventually, this building would be used as a cold-weather shelter for the homeless.

Flying Saucers!

1947 was the year of the famous Roswell Incident in New Mexico. It turns out that there were many flying saucer sightings that year.

Deaths

Fullerton co-founder George Amerige died.

Local pioneer Edmund Beasley also died.

The bodies of some soldiers killed in the War were returned home to be buried in Fullerton.

A memorial plaque, honoring former students who died in the War, was dedicated in the high school auditorium.

Stay tuned for top stories from 1948!

-

Fullerton: The Boom Years (a book report)

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

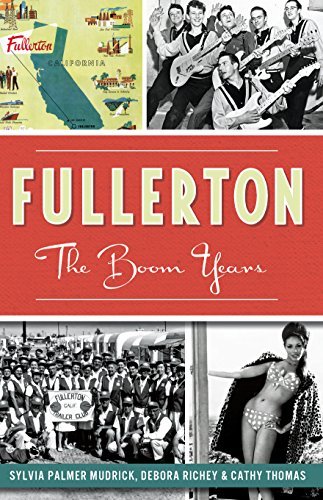

As part of my research into Fullerton history, I’ve just finished reading an excellent book called Fullerton: The Boom Years by Sylvia Palmer Mudrick, Debora Richey, and Cathy Thomas. The book vividly chronicles Fullerton’s extraordinary growth after World War II, as orange groves gave way to housing subdivisions, shopping centers, schools, and industry.

I present here a book report on some interesting things I learned.

Like much of Southern California, Fullerton experienced rapid growth and development after World War II. The population grew from 10,442 in 1940 to 85,987 in 1970.

Housing

Housing restrictions and shortages created by the Great Depression and the War led to a massive pent-up demand. And after the War, the floodgates opened.