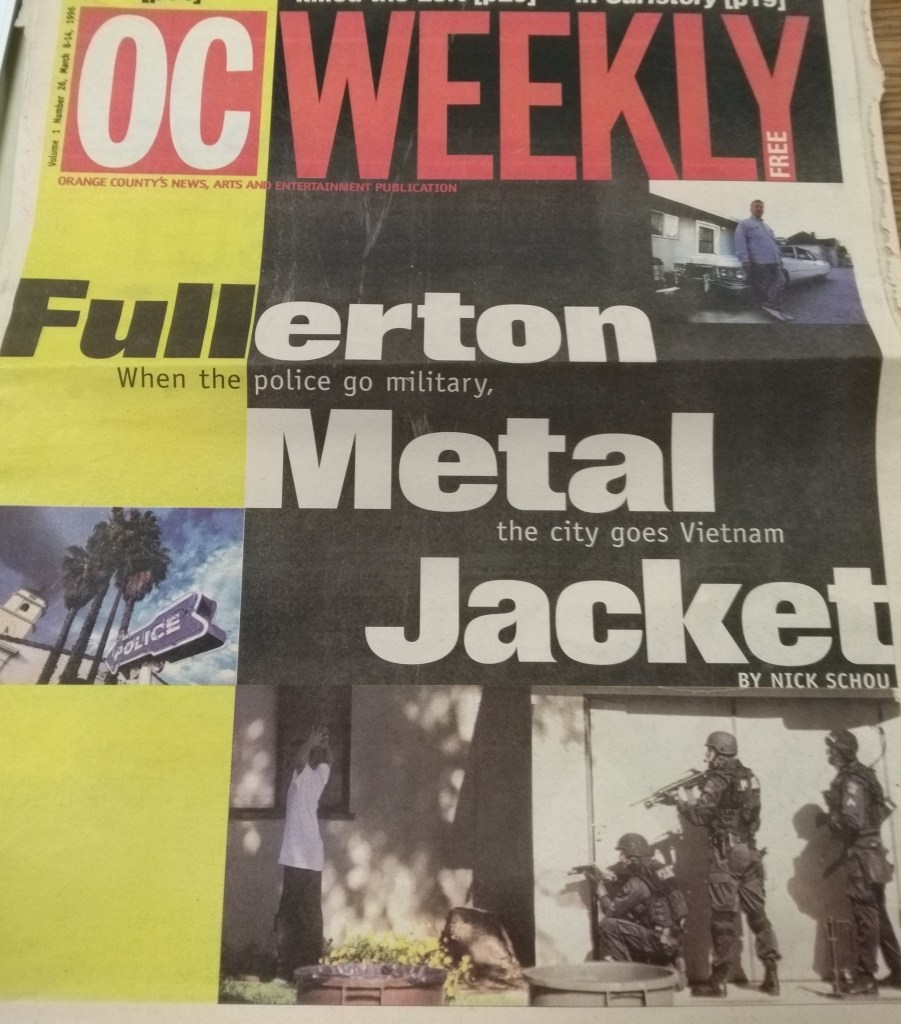

-

Fullerton in 1954

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library has microfilm from the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune newspaper stretching back to 1893. I am in the process of reading over the microfilm, year by year, to get a sense of what was happening in the town over the years, and creating a mini archive. Below are some news stories from 1954.

National and International News

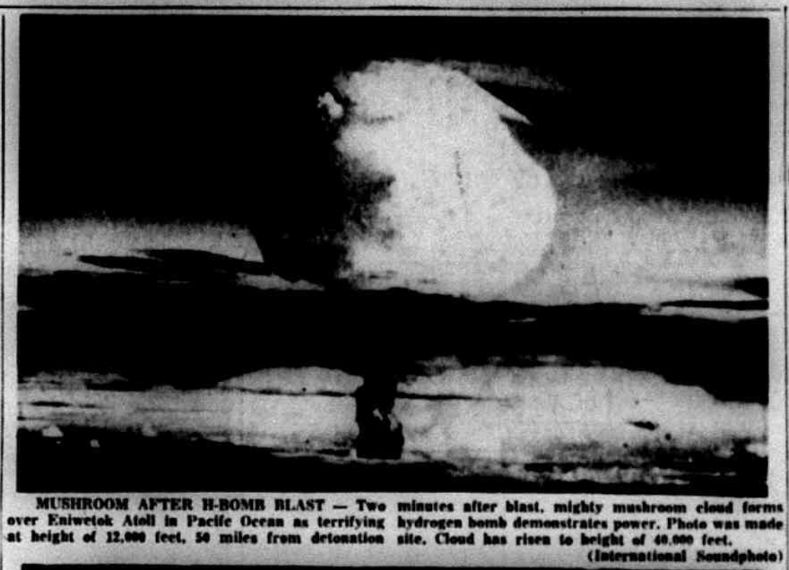

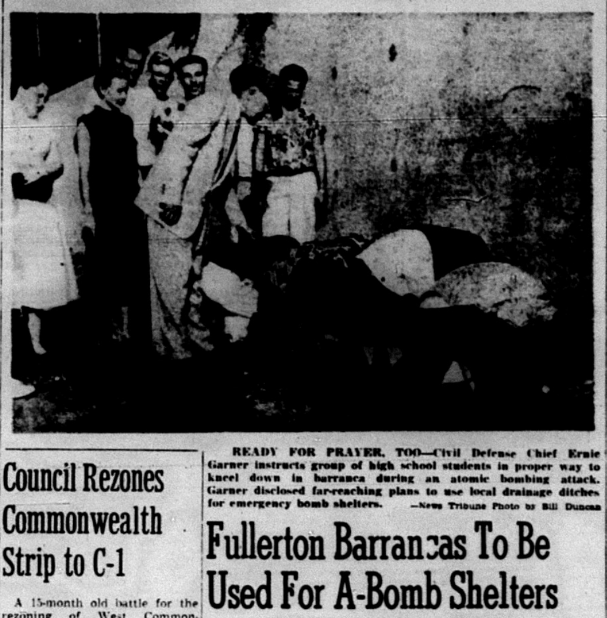

In national and international news, the Cold War arms race was escalating, with America testing increasingly devastating nuclear weapons, like the Hydrogen bomb.

This prompted a national fear of/preparation for atomic war.

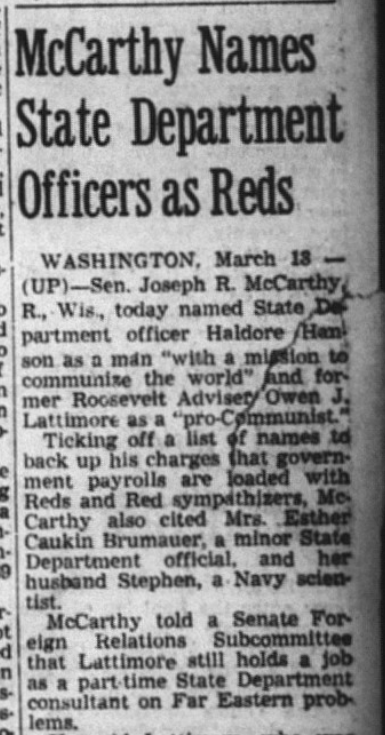

Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare campaign, accusing many people of being secret communists, encountered its first major pushback after McCarthy started going after U.S. Army officials. The Army-McCarthy hearings signaled the end of McCarthy’s popularity and influence.

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court decided the famous Brown v. Board of Education case, declaring school segregation unconstitutional.

Immigration

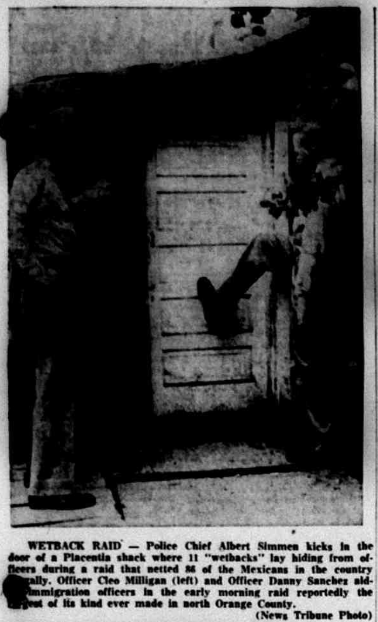

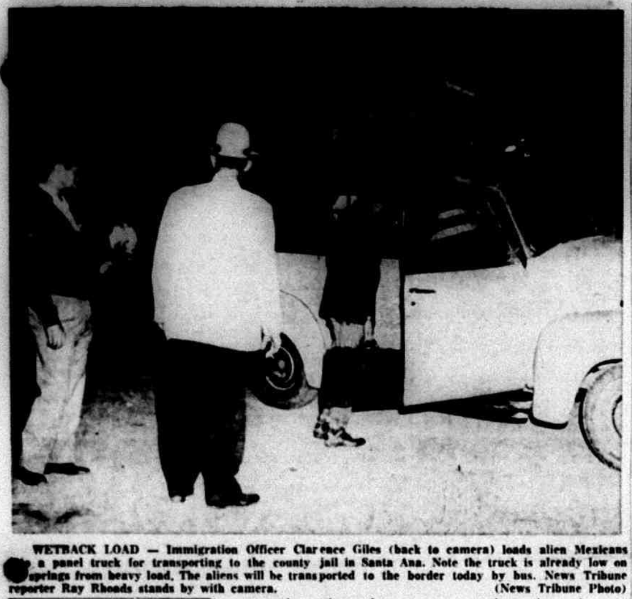

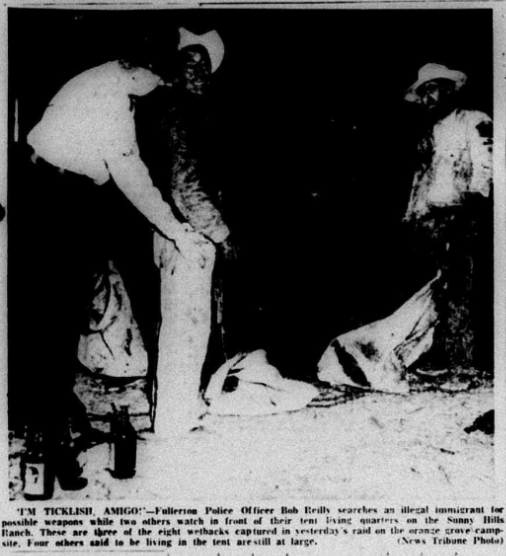

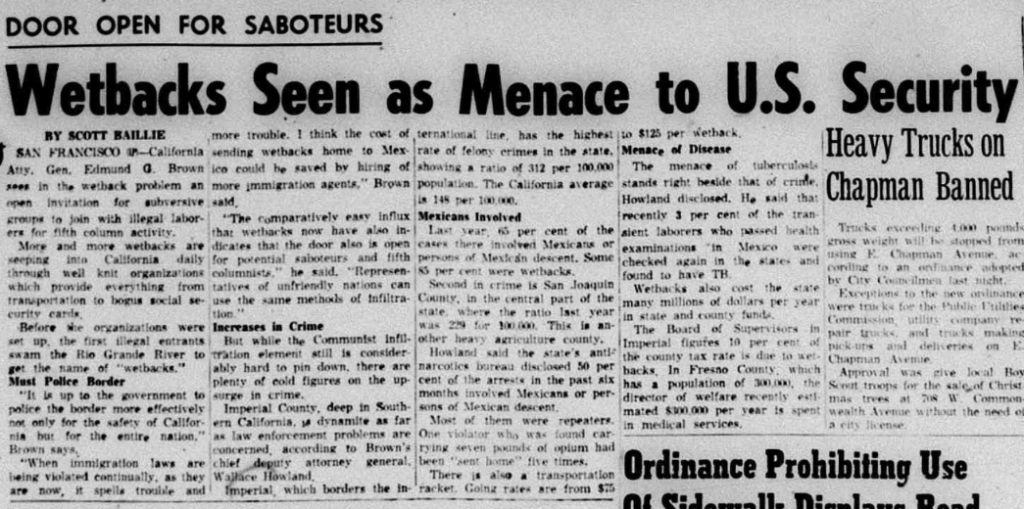

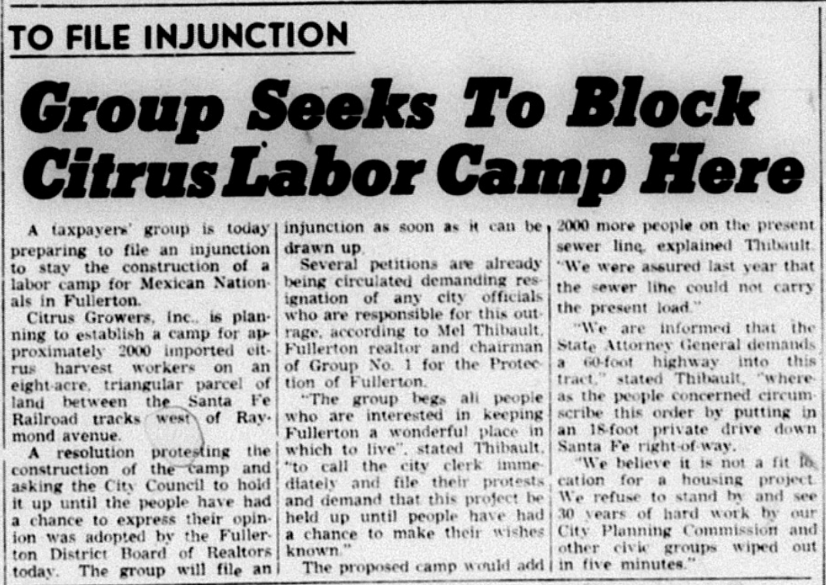

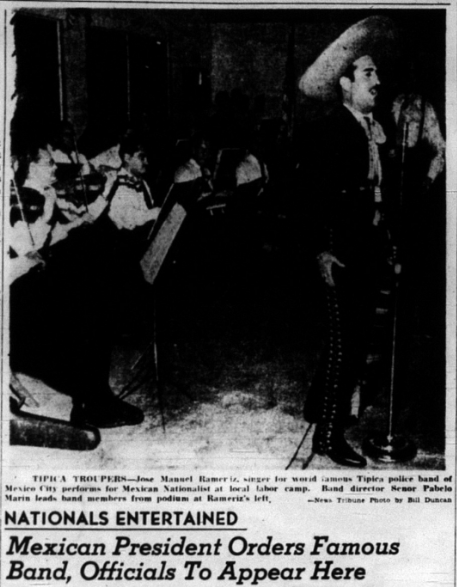

In 1954, the Eisenhower administration undertook a massive deportation program called Operation Wetback. This took place throughout the Southwest, including here in Fullerton. At that time, the Fullerton Police department often cooperated directly with federal immigration officials.

Throughout 1954, the Fullerton News-Tribune contained numerous articles about immigration raids and arrests. Back then, even the newspapers used the racial slur “wetback” to refer to undocumented immigrants. Below are a few such clippings from the News-Tribune.

Operation Wetback was officially launched in June, 1954. Unfortunately, the microfilm archives are missing the months of June, July, and August of that year. So, I decided to pay a visit to the Anaheim Heritage Center to look at microfilm from their newspaper of record from that era, the Anaheim Bulletin. Here are a few articles I found there:

The Anaheim Bulletin contains an article entitled “More Mexicans to be Recruited for Farm Work” which tells of a plan to recruit “legal” immigrants to replace the “illegal” ones. The truth is that there was already a widespread farm labor recruitment program in place at this time (the Bracero Program), and the majority of growers preferred to hire illegal workers because there were no legal protections for such workers. Nevertheless, the full brunt of punishment fell on the workers, not the growers, for a highly problematic immigration system.

In a move symbolic of the times, US Immigration Service abandoned Ellis Island.

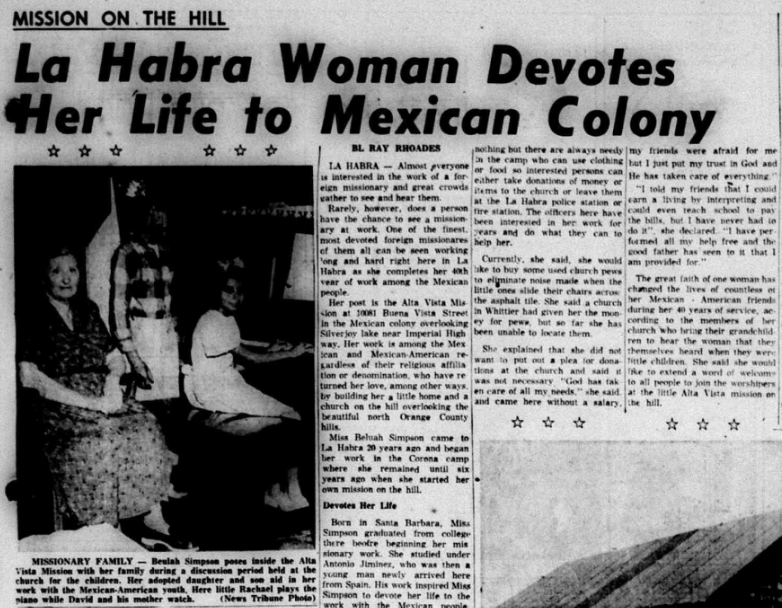

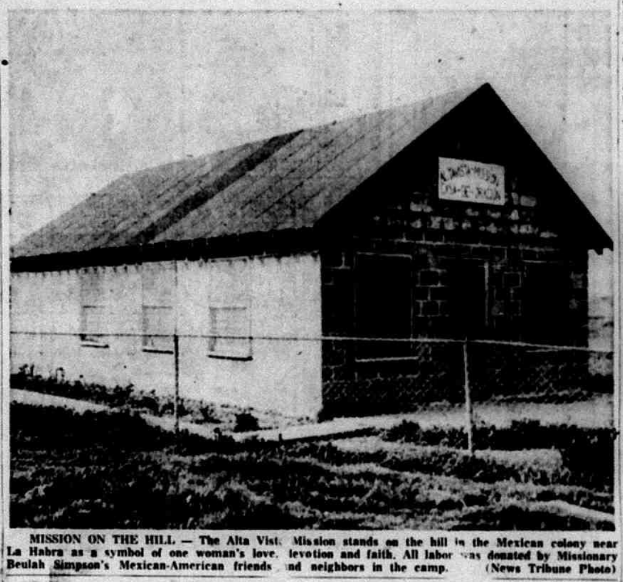

At this time, many Mexican-Americans in Orange County lived in segregated barrios or “colonias” (labor camps). The News-Tribune features an article about a woman who had started a small church in a Mexican camp on Imperial Highway.

“Her post is the Alta Vista Mission at 10081 Buena Vista Street in the Mexican colony overlooking Silverjoy lake near Imperial Highway. Her work is among the Mexican and Mexican-American regardless of their religious affiliation denomination, who have returned her love, among other ways, by building her a little home and a church on the hill overlooking the beautiful north Orange County hills,” the News-Tribune reported. “Miss Beluah Simpson came to La Habra 20 years ago and began her work in the Corona camp where she remained until six years ago when she started her own mission on the hill.”

Government and Politics

In 1954, Fullerton City Council was Howard Cornwell, Cecil Crew (mayor), William Kroeger, Phillip Twombly, and Hugh Warden.

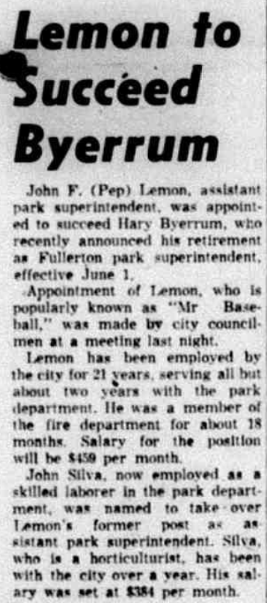

Fullerton Park Superintendent (and alleged former Klansman) Harry Byerrum retired and was replaced by “Pep” Lemon. There is a park in Fullerton named after Byerrum.

“What consisted of a four-acre Commonwealth Park (now Amerige Park) back in 1923, when Byerrum was hired as a laborer, is now a municipal network of 14 parks covering an area of about 100 acres. What once consisted of two employees, has grown to a park department staff of 18 persons,” the News-Tribune reported.

And here are some other local politicians elected to office in 1954.

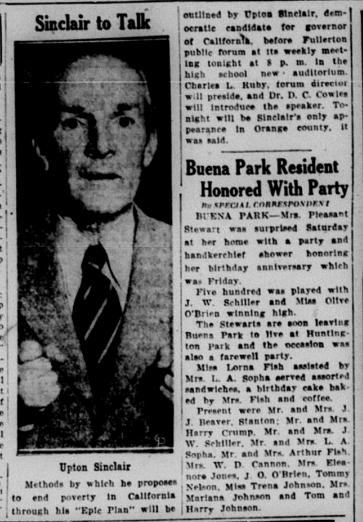

Sam Collins on Trial for Corruption

Former California State Assemblymember Sam Collins, a Republican from Fullerton, was indicted and stood trial for allegedly accepting bribes to get his friend a liquor license in Buena Park. His son (also named Sam Collins) was also indicted.

The Collinses were tried on three charges: conspiracy to commit the crime of asking of receiving bribes by public officers, conspiracy to commit grand theft, and grand theft. They were accused of taking $7,500 from George Underwood of Buena Park in order to acquire a liquor license.

The first Collins trial ended with a hung jury.

It was possible they may not have to stand for another trial. Stay tuned!

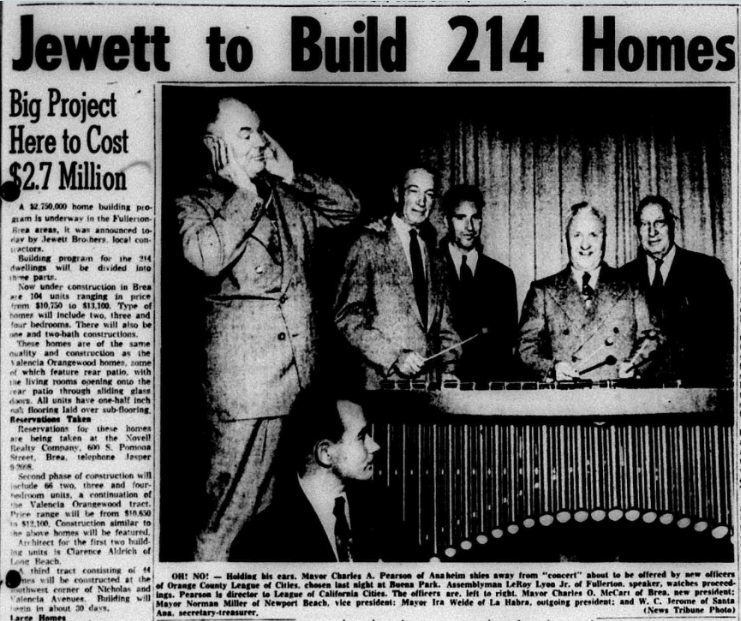

Growth

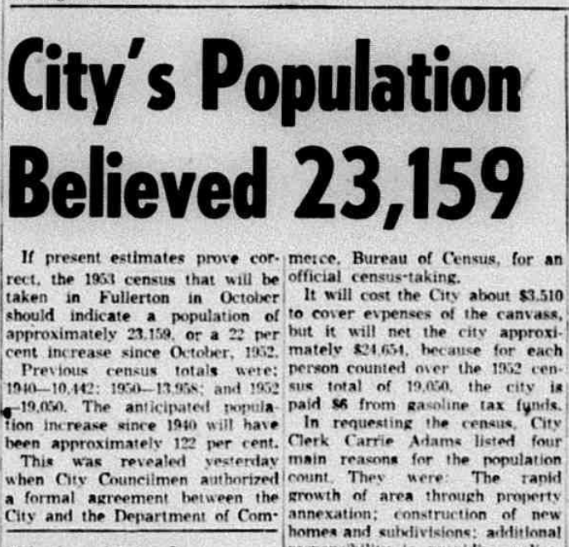

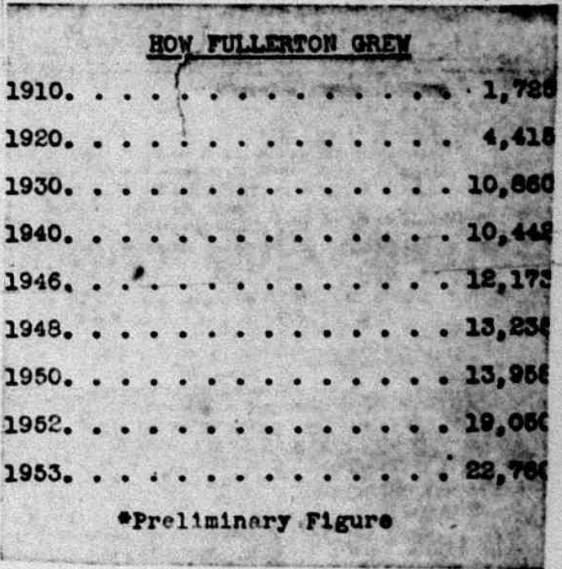

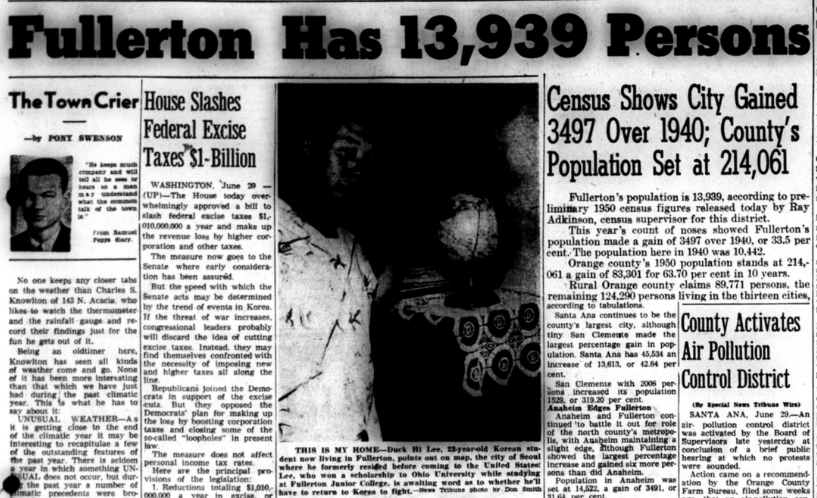

Throughout the 1950s, Fullerton was experiencing dramatic growth. In 1954, the city’s population was over 27,000.

New shopping centers were approved and constructed.

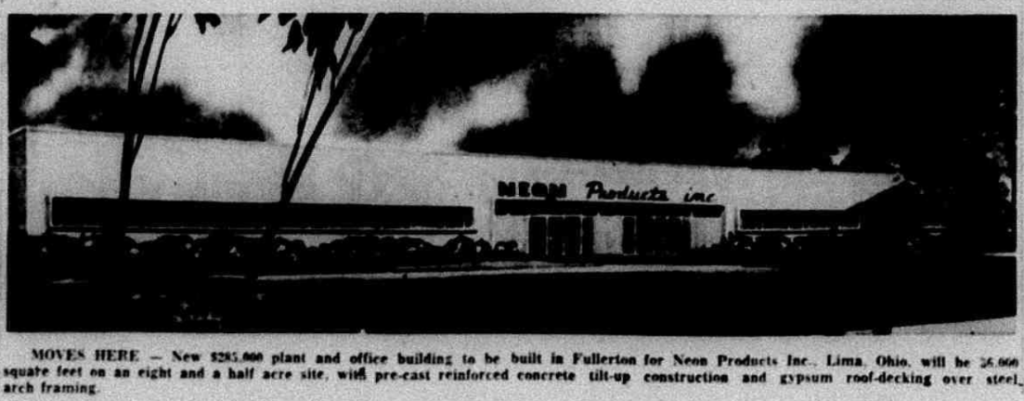

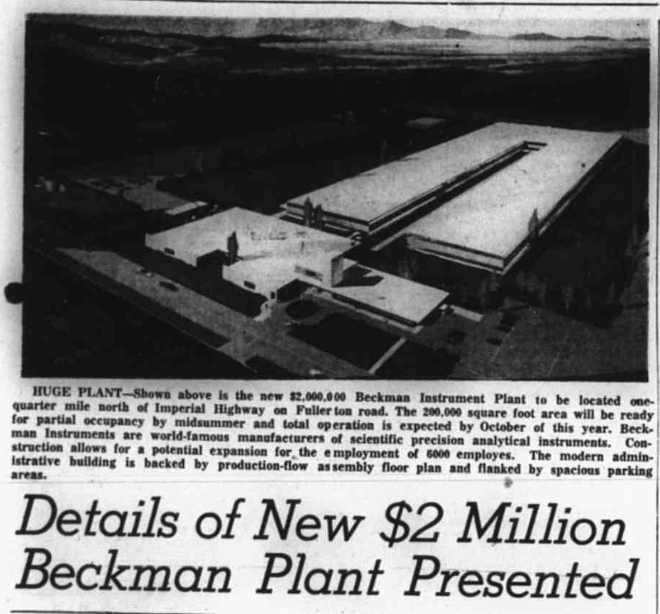

New industrial plants opened up shop in specially zoned areas–mostly on the south side of town, with the major exception of the large Beckman Instruments plant on the north side near the La Habra border.

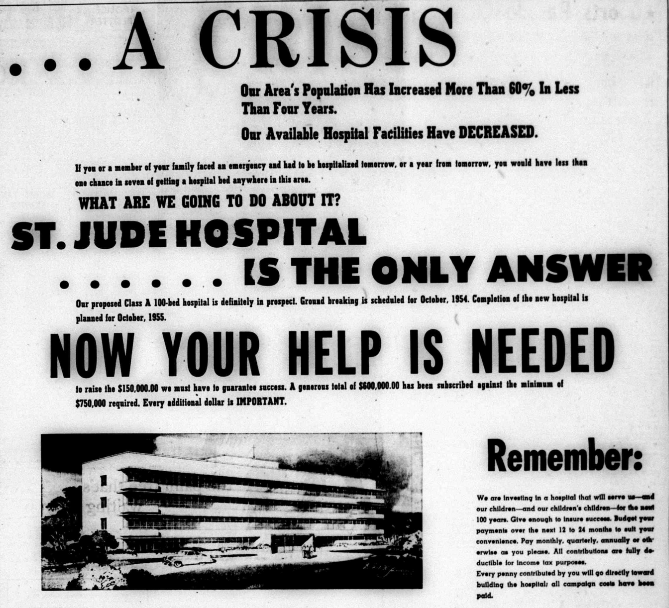

As the population grew, so did the need for a larger hospital. Fundraising efforts were underway for St. Jude.

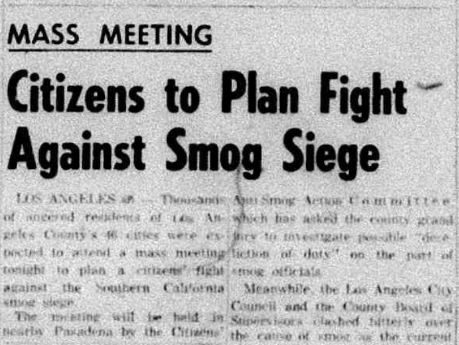

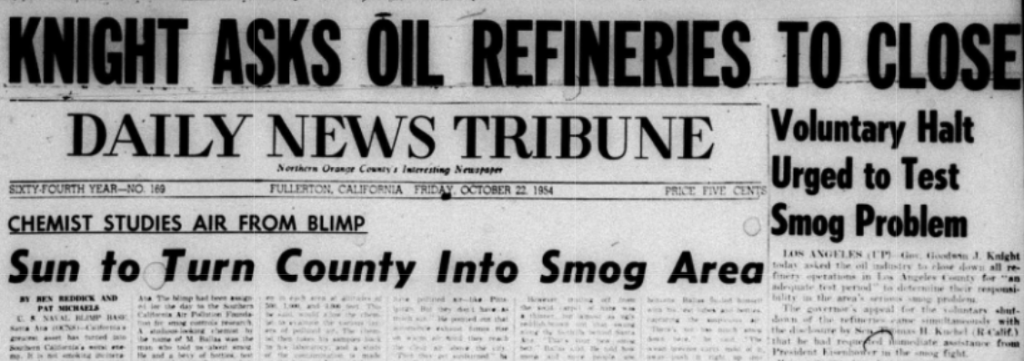

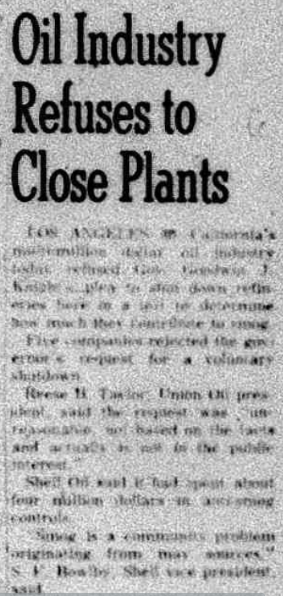

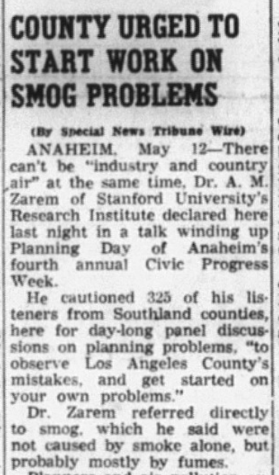

One unfortunate by-product of growth in southern California was smog.

Governor Goodwin Knight asked the oil companies to close their refineries as the state grappled with the smog problem.

The oil companies said, “No.”

Housing

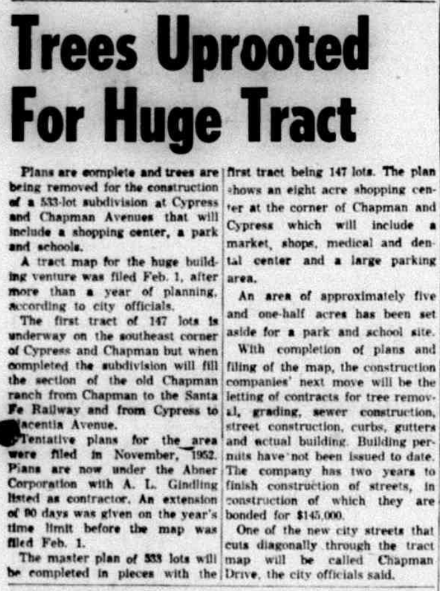

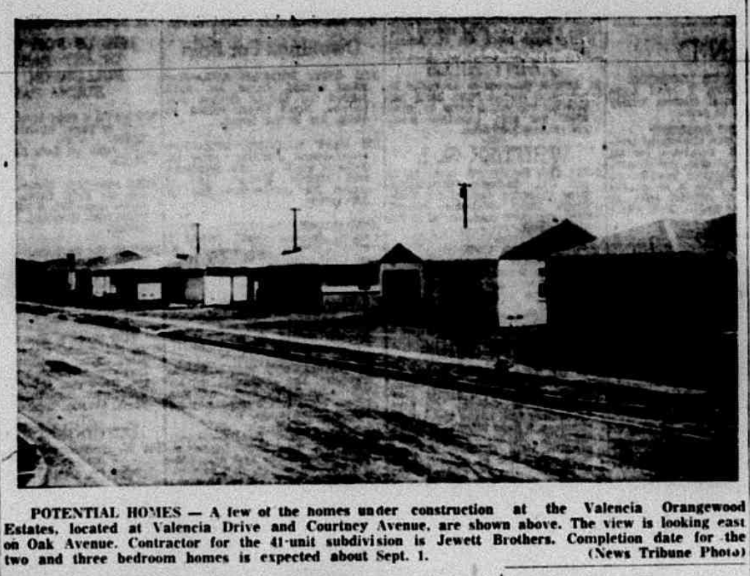

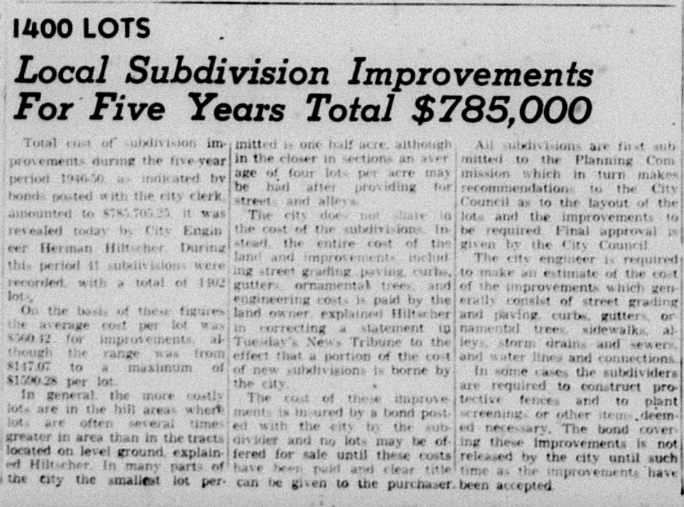

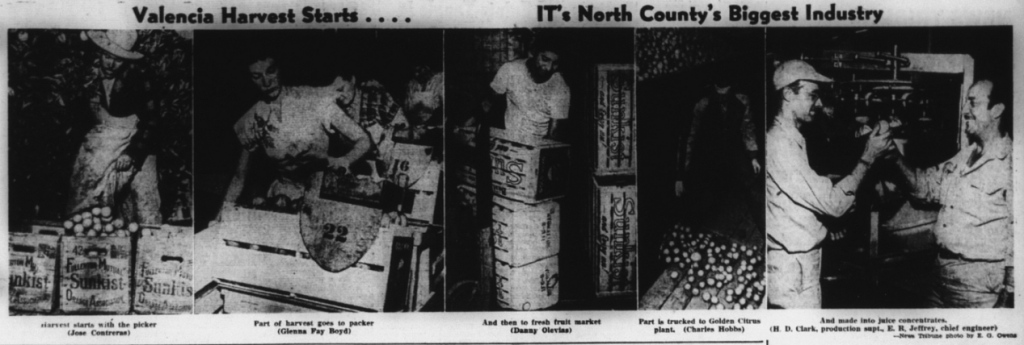

Throughout the 1950s, thousands of acres of orange groves were plowed under to may way for shopping centers, industrial plants, and sprawling housing subdivisions.

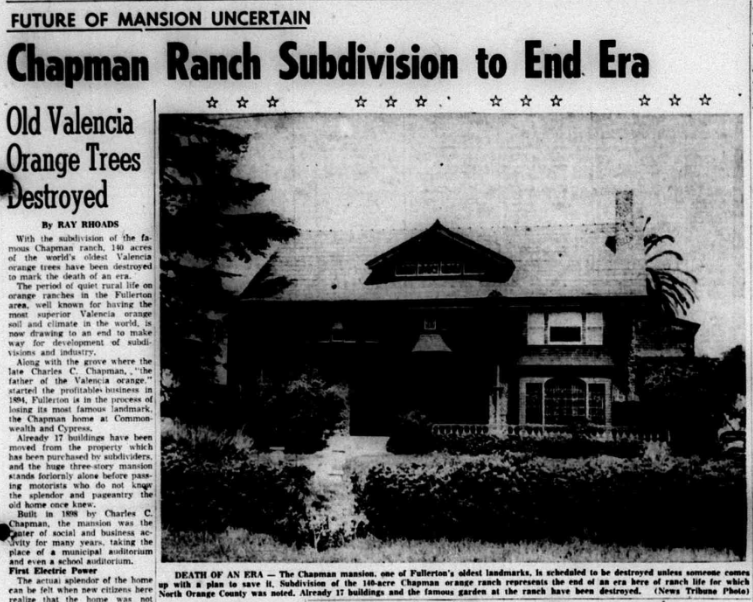

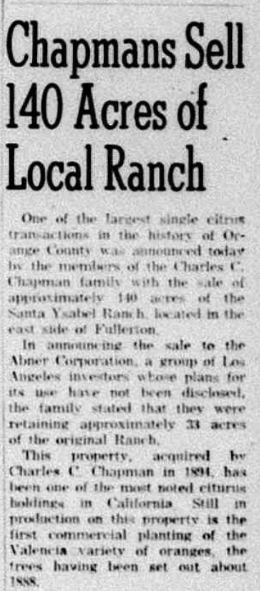

Perhaps most symbolic of this transformation was the subdivision of the Chapman Ranch.

“With the subdivision of the famous Chapman ranch, 150 acres of the world’s oldest Valencia orange trees have been destroyed to mark the death of an era,” the News-Tribune reported. “The period of quiet rural life on orange ranches in the Fullerton area, well known for having the most superior Valencia orange soil and climate in the world, is now drawing to an end to make way for development of subdivisions and industry.”

Charles C. Chapman, “the father of the Valencia orange” and Fullerton’s first mayor, got into the orange business in 1894 and became one of the wealthiest and most successful local growers.

There was a question of what would happen to the stately Chapman mansion, built in 1898–once a center for social and cultural gatherings.

“Even though the death of the old landmark stirs deep regret in all long-time citizens here, so far all attempts to keep the house intact have failed. No one can find an answer to the question, “What to do with an 11-bedroom mansion?” Suggestions of turning it into a museum and park have been looked on with favor, but the question has arisen: who would finance such a venture?” the News-Tribune asked.

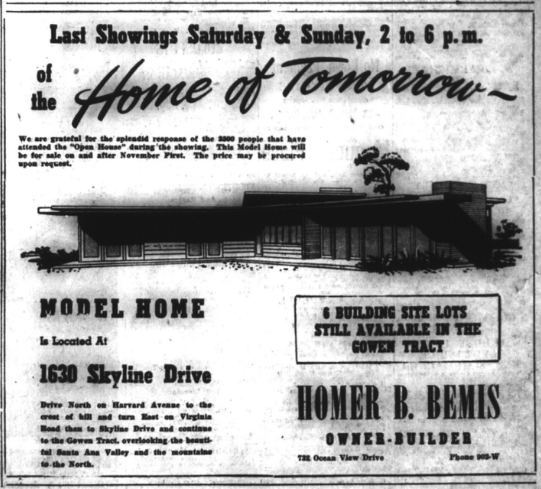

Famous mid-century modernist architect Joseph Eichler contributed to post-war Fullerton suburbanization.

On their web site, Fullerton Heritage writes:

“In 1955, Eichler, a merchandising wizard, convinced his two principal architects, A. Quincy Jones and Frederick E. Emmons, to appear on the “House That Home Built” segment of the NBC Home television show that came on daily after the Today Show from 1954 to 1957. On the nationally syndicated show, co-hosted by Hugh Downs and Arlene Francis, Jones and Emmons offered to create house plans for any developer who could come up with $200. The plans were designs that Jones and Emmons had created earlier for Eichler. The local building firm of Pardee-Phillips took up the challenge and constructed over 300 Eichler homes, naming the tracts the Fullerton Grove development. Advertised as the “Forever House” model, the aluminum, glass, steel, and masonry dwellings sold from $12,950 to $19,500 for the deluxe model, requiring a $1,250 to $2,000 down payment (with little or no down payment for veterans).

The architects offered seven floor plans for the three- and four-bedroom, two-bath homes that featured floor-to-ceiling fireplaces and glass walls, color coordinated kitchens and bathrooms, birch cabinets, sliding glass doors, and an electronic weather control system. Advertising extolled the “Dream Kitchen of Tomorrow” that contained 14 major built-in items. The homes were noted for their simple, plain façades, few windows, flat roofs, and carports situated front and center. A unique touch was orange trees in the front and backyards, a tribute to Fullerton’s agricultural past. The Fullerton Grove development quickly sold out.

Fullerton was not the only city to benefit from the television offer of Jones and Emmons. Local builders in the cities of Cleveland, Chicago, Denver, San Francisco, and Kansas City also constructed similarly styled Eichler homes.”

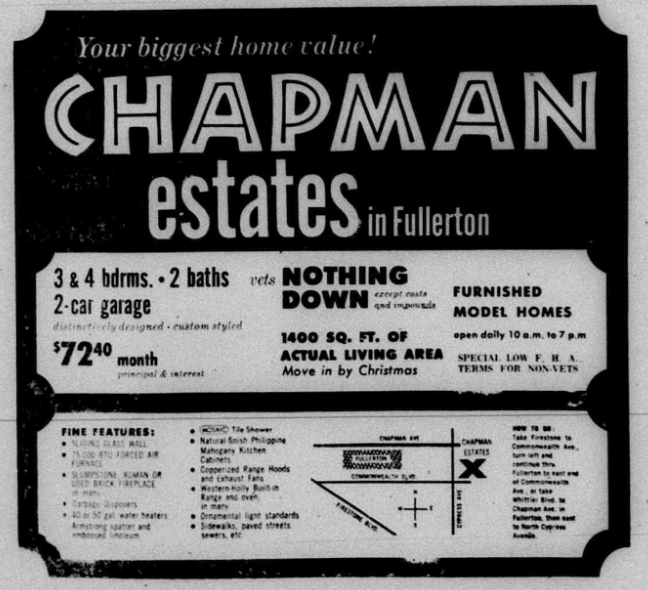

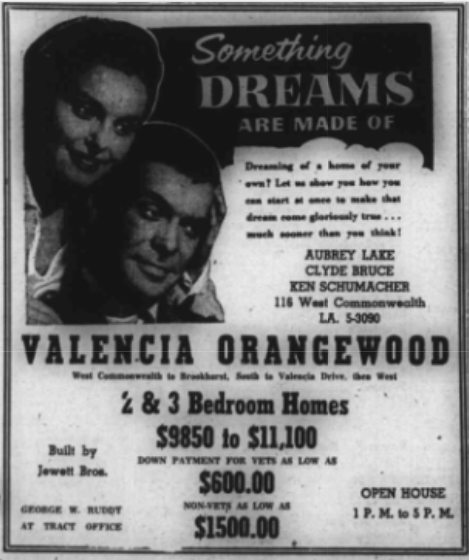

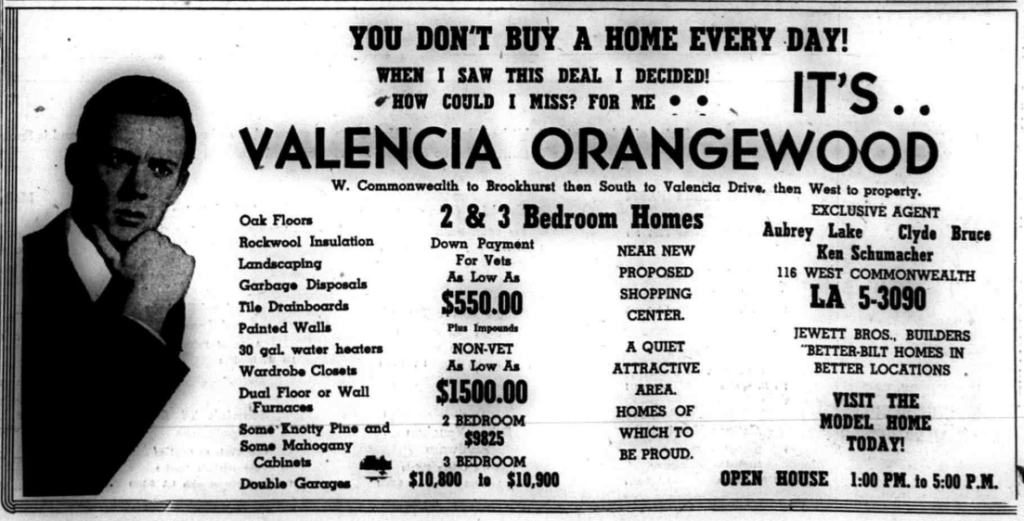

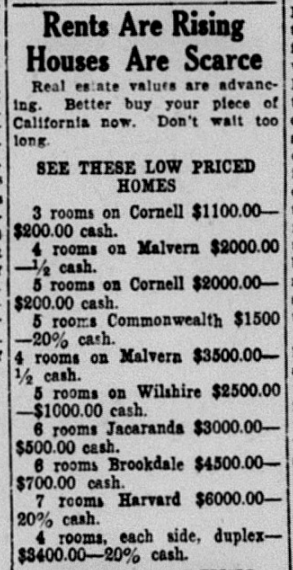

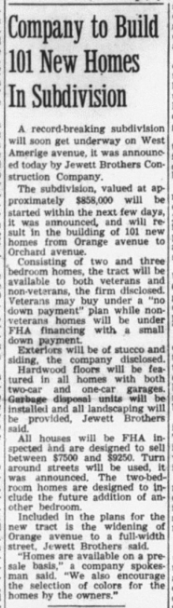

Numerous advertisements appear in the Fullerton News-Tribune for homes in newly-built subdivisions. What strikes me is how affordable these homes were. This was partly because of federally-backed loans and “no money” down offers for veterans.

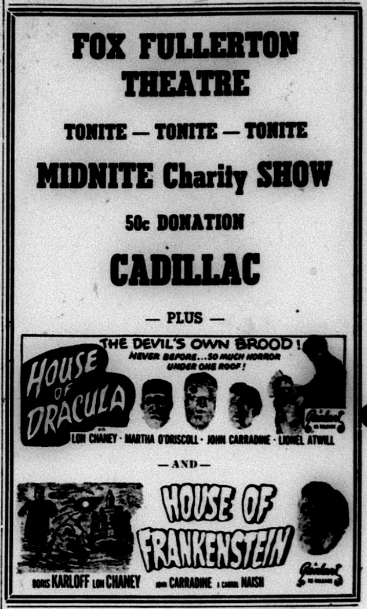

Culture and Entertainment

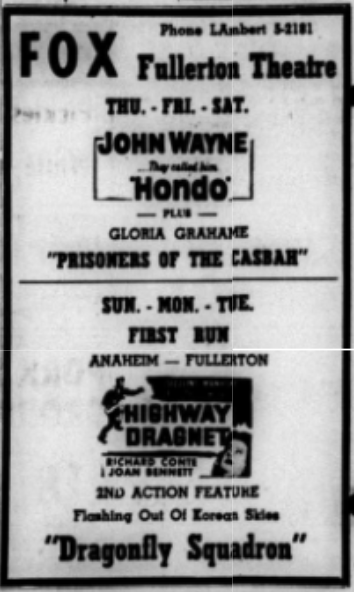

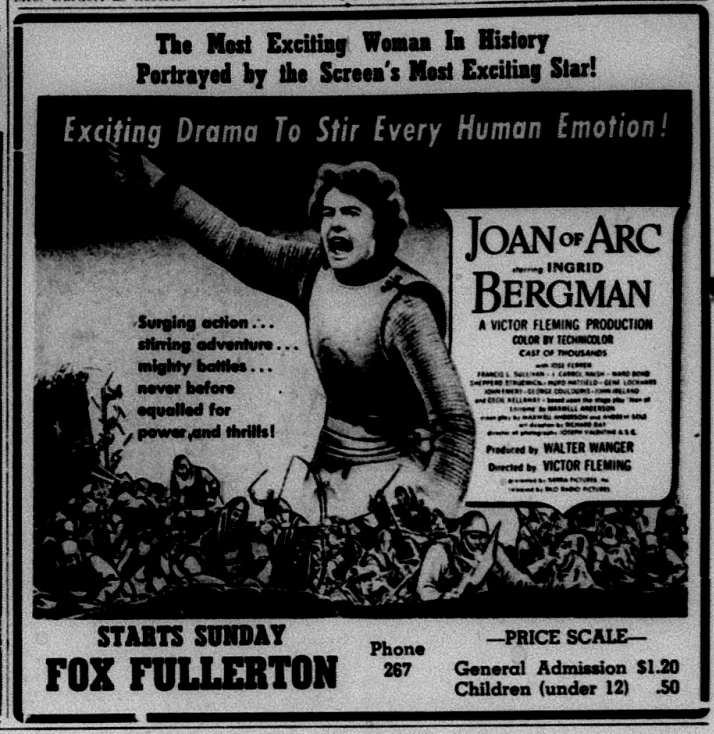

For culture and entertainment, Fullertonians went to movies at the Fox Theater. Westerns were quite popular, often presenting a sanitized vision of American westward expansion that valorized white settlers, stereotyped Native Americans, and ignored or downplayed the genocide that was the endgame of Manifest Destiny.

Fullerton was home to at least two famous female authors: Ruby Berkeley Goodwin and Ethel Jacobsen, who would sometimes share their works at local gatherings.

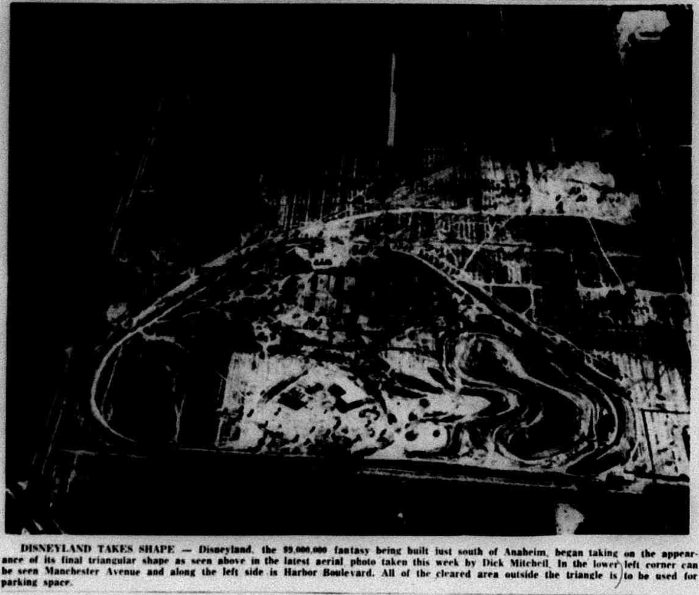

Something new and exciting was coming to Anaheim next door: Disneyland!

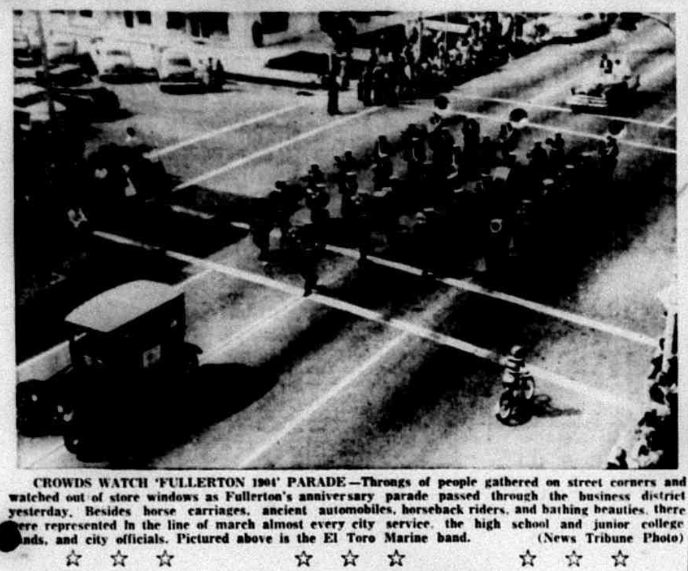

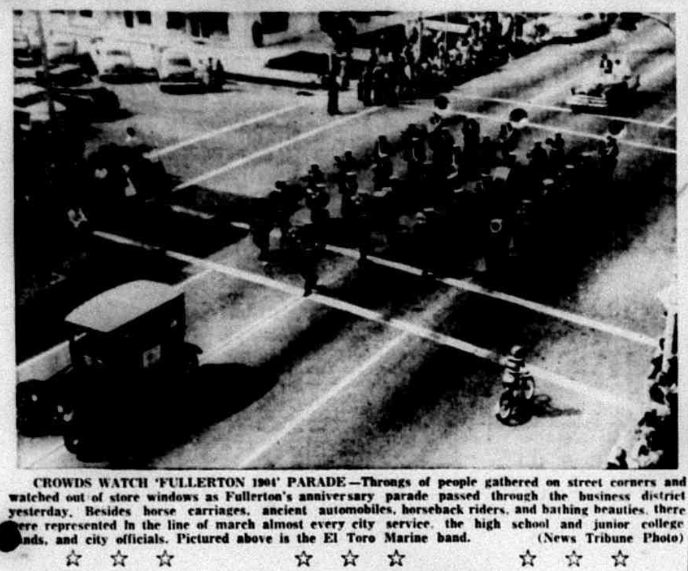

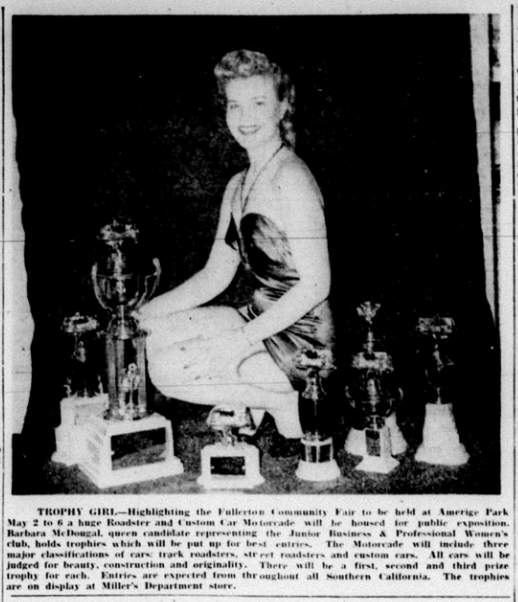

Fullerton celebrated the 50th anniversary of its incorporation as a city with a Community Parade and other events which focused on what life was like in 1904.

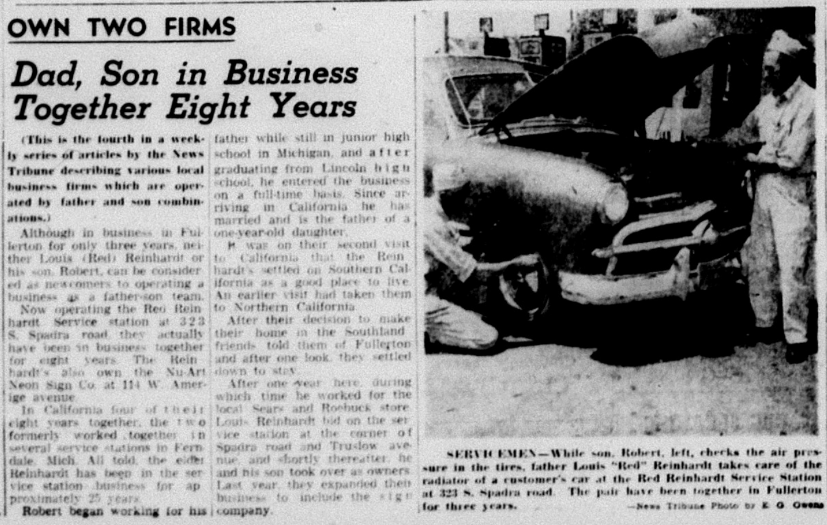

Some Businesses

Here are advertisements for some of the businesses that existed in Fullerton in 1954, with a particular focus on restaurants.

Sports

In the 1950s, the minor league baseball team the Los Angeles Angels played games at Amerige Park in Fullerton.

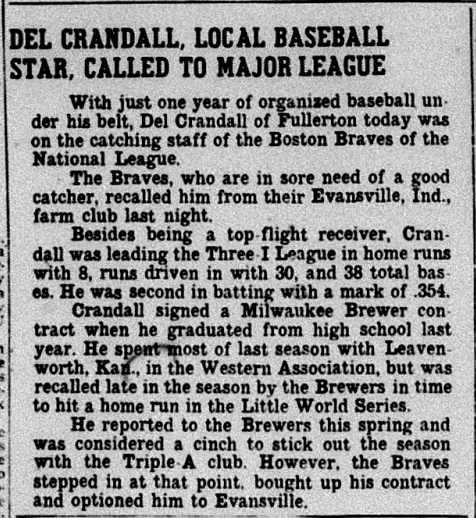

Hometown hero Del Crandall was making Fullertonians proud as catcher for the Milwaukee Braves.

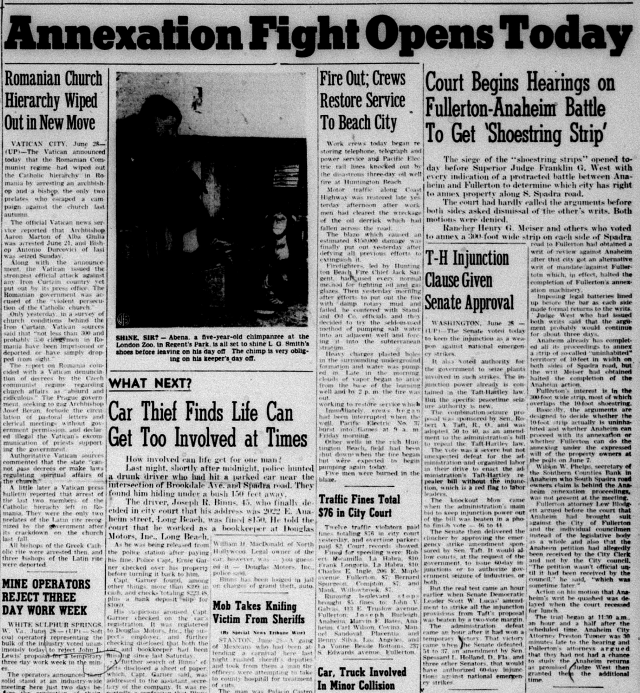

Annexation

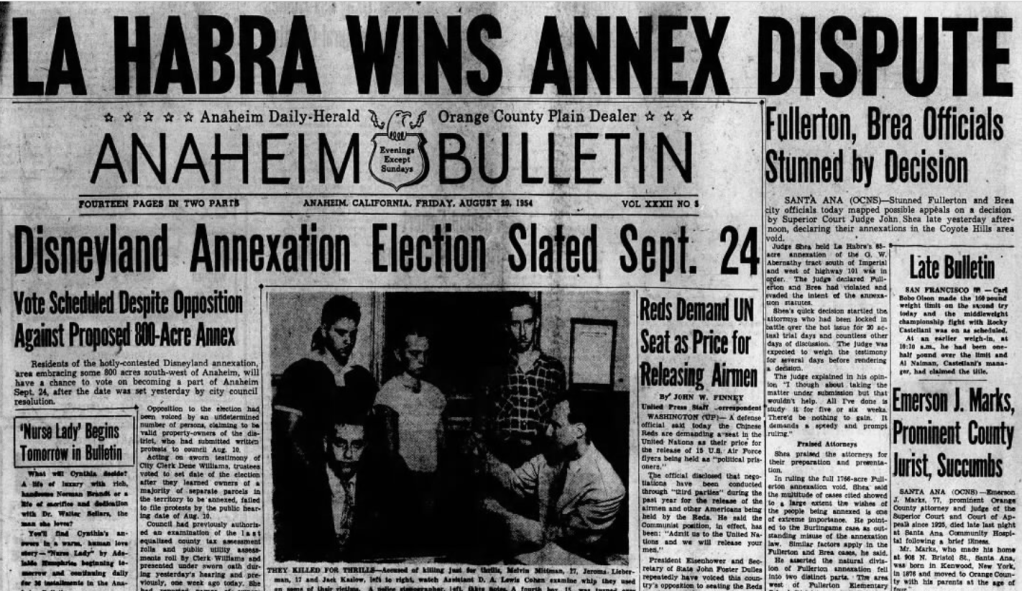

In the early 1950s, there were several disputes between Fullerton and surrounding cities over annexation of unincorporated land. In 1954, a judge ruled in favor of La Habra’s claim against Fullerton and Brea for a large stretch of land north of Fullerton. Below is another clipping from the Anaheim Bulletin:

Fire

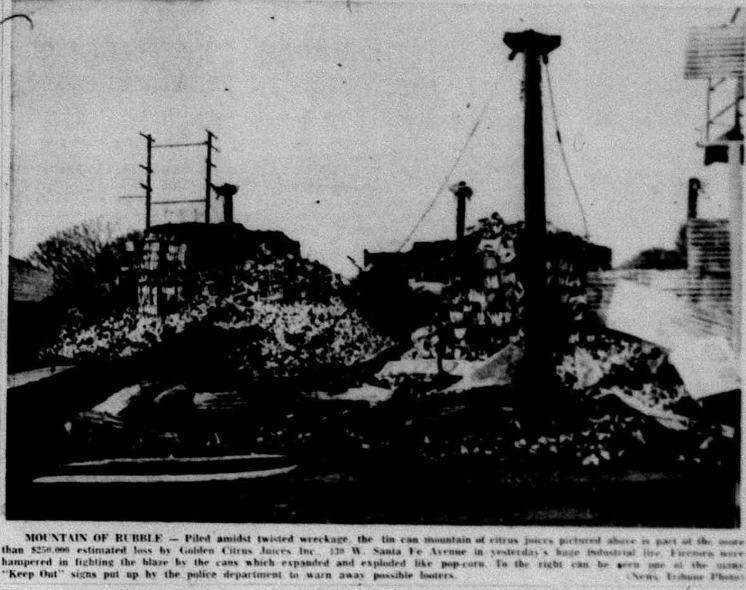

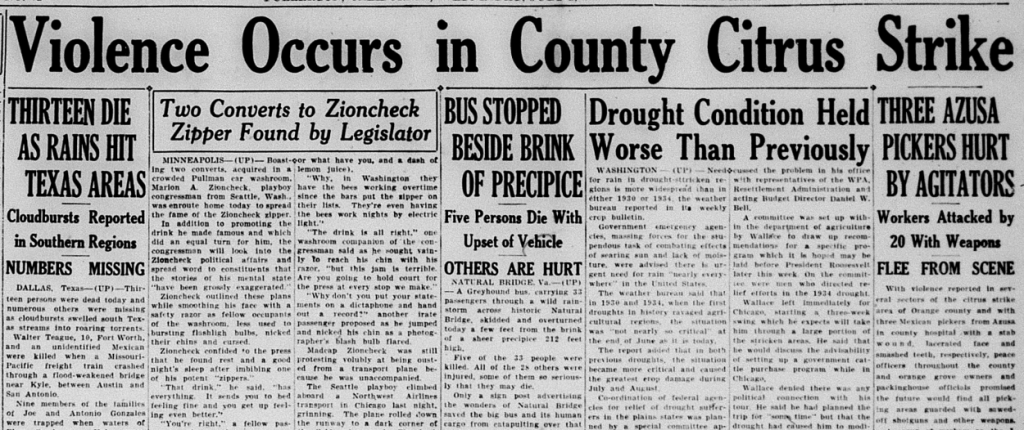

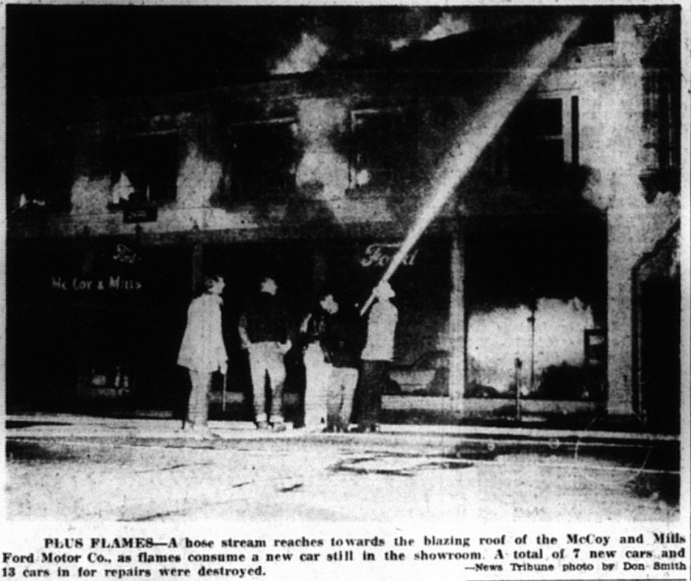

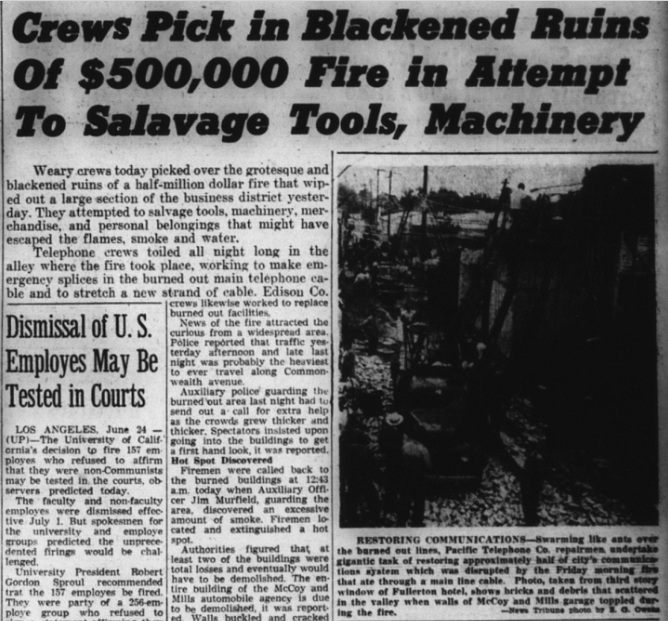

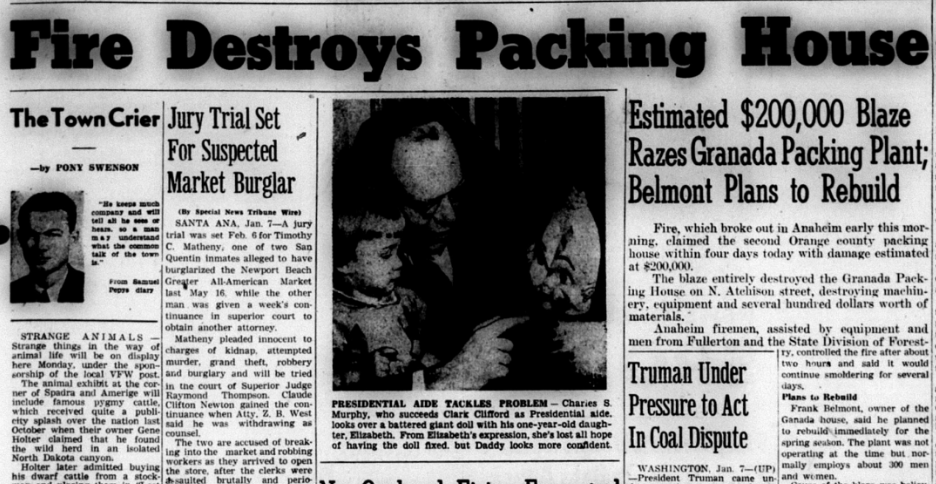

Fullerton suffered the worst fire in its history as a mighty blaze destroyed several packinghouses along the railroad tracks.

History

An anniversary issue of the News-Tribune contained photos of some notable long-time Fullerton residents who were still alive like Grace McDermont Ford, Mrs. Chapman, Otto Des Granges, Annette Amerige, C.E. Holcomb, and O.M. Thompson,

Stay tuned for top stories from 1955!

-

Fullerton in 1953

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library has microfilm from the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune newspaper stretching back to 1893. I am in the process of reading over the microfilm, year by year, to get a sense of what was happening in the town over the years, and creating a mini archive. Below are some news stories from 1953.

National and International News

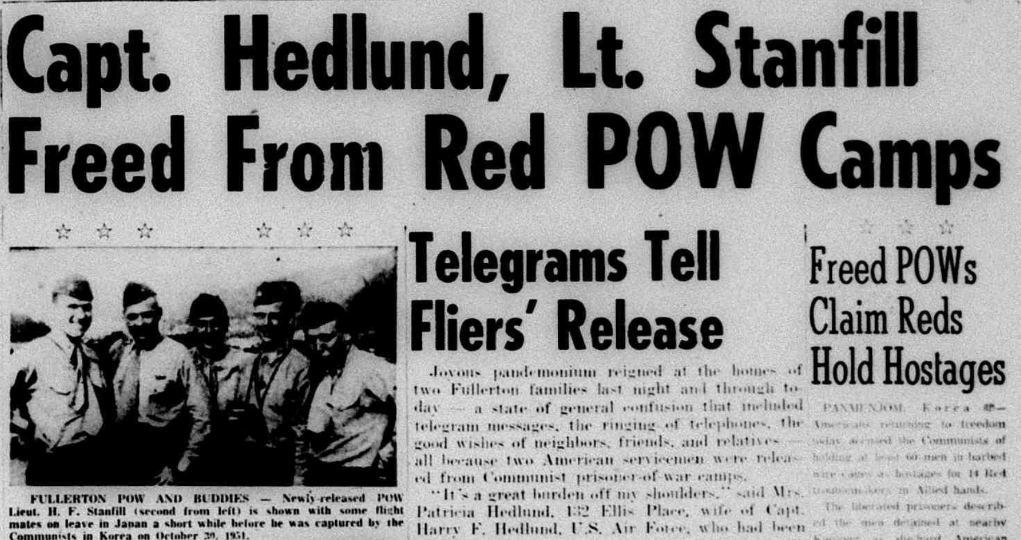

In international news, the Korean War ended with the country just as divided as when the conflict began. Several POWs were released, including some from Fullerton.

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin died, and after a power struggle, Nikita Khruschev became the leader of the USSR.

The prime minister of Iran, Mohammad Mossadegh, was ousted in a CIA-backed coup that would see the re-installation of the Shah who was much more friendly to western oil interests.

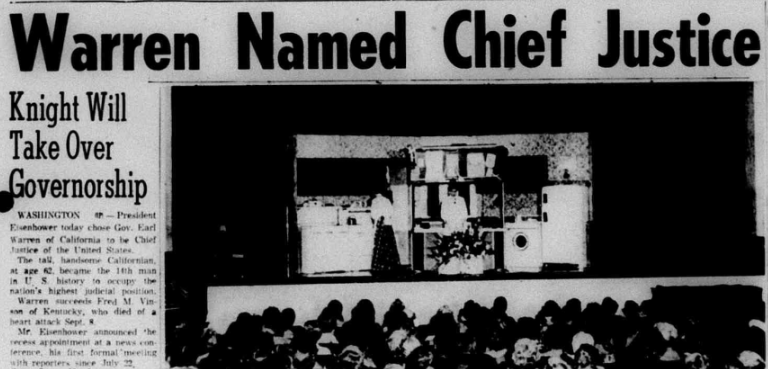

Former California governor Earl Warren was named Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court. The Warren court would make a number of landmark civil rights decisions, such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Immigration

In 1953, raids and crackdowns against undocumented immigrants were increasingly common. Today, supporters of this kind of activity like to avoid racialized language–instead saying that such efforts are about following the law, etc. But in 1953, proponents were much more straightforward. The Eisenhower mass deportation program of 1954-55 was called “Operation Wetback.” It did not solve the problem of illegal immigration because it did not focus on root causes. What it did do was terrorize and violate the rights of many folks, including many American citizens–the vast majority of whom were workers who had been recruited by American businesses that preferred undocumented workers.

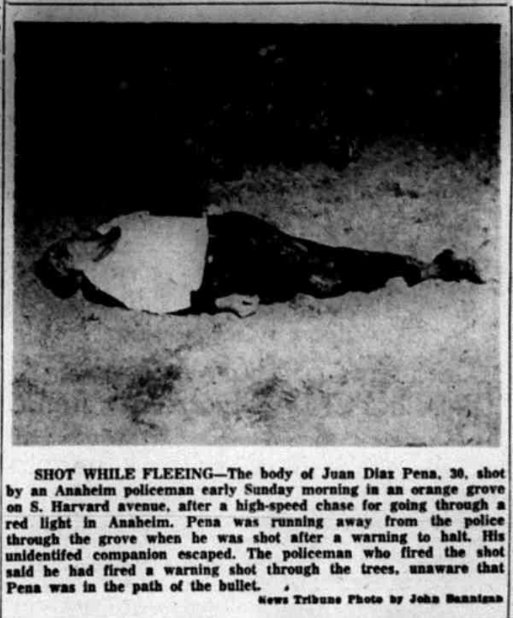

In 1953, police shot and killed a Mexican man named Juan Pena Diaz.

Growth

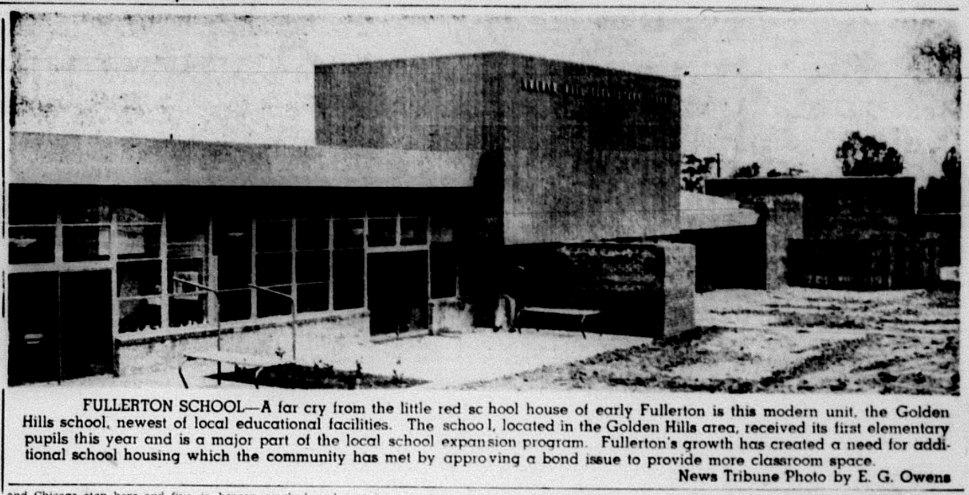

Fullerton continued its phenomenal postwar growth, with new shopping centers, housing subdivisions, industry, and schools replacing orange groves.

Housing

Many orange groves were replaced by new housing subdivisions, including the 140-acre Chapman Ranch.

Housing was much more affordable in the 1950s.

The preferred type of housing in Fullerton was the single-family home. Trailer parks and multi-family apartments were frowned upon and often denied approval.

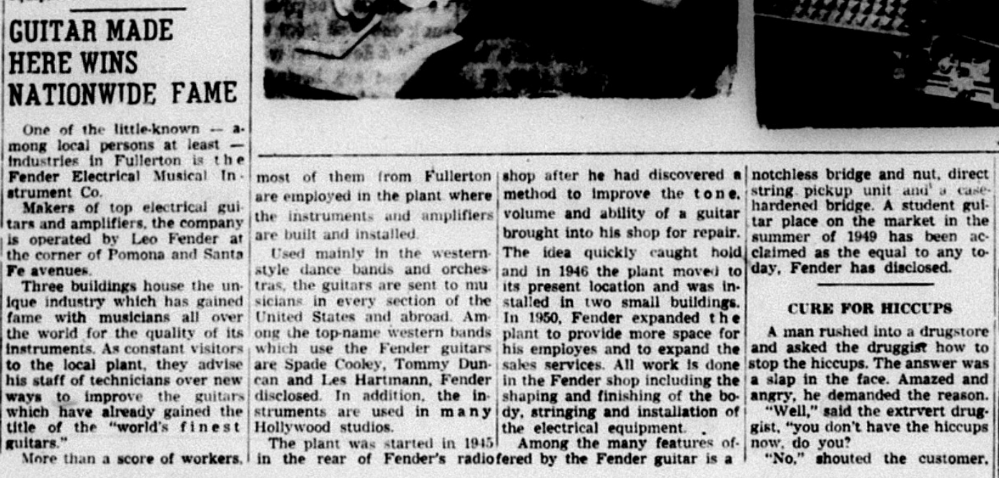

Industry

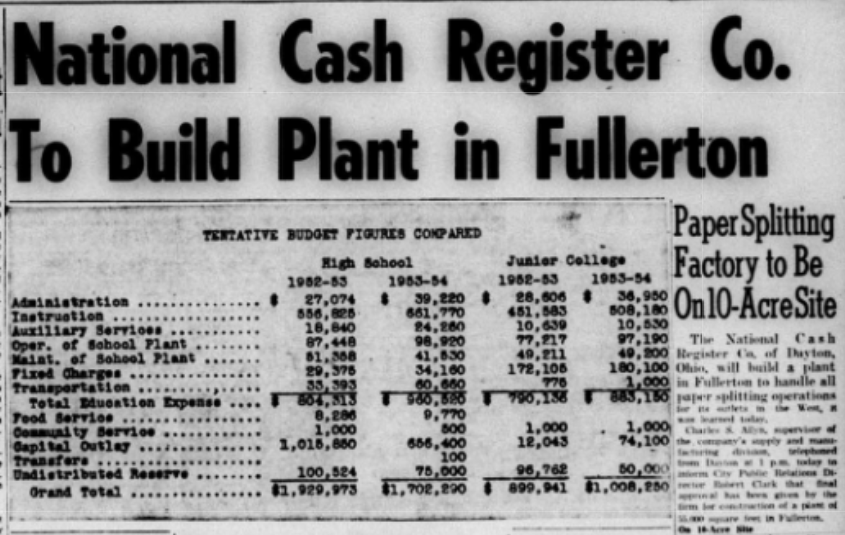

New industries located in Fullerton including the following:

Beckman Instruments,

“The entire plant,” said Beckman, “has been planned to harmonize with the natural beauty of the area.” Much of the original orange grove will be maintained and additional landscaping will be in keeping with the established suburban atmosphere.”

Sylvania Electric Products,

National Cash Register,

F.E. Olds,

Fender Instruments,

US Motors,

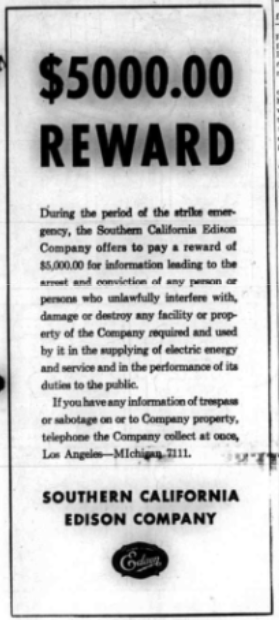

In labor news, employees of Edison went on strike.

Edison responded by advertising a reward for information leading to the arrest of strikers who broke the law.

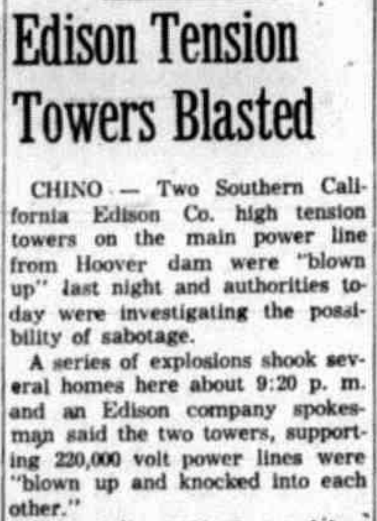

Part of Edison’s concern was perhaps justified, as someone blew up some Edison towers in Chino.

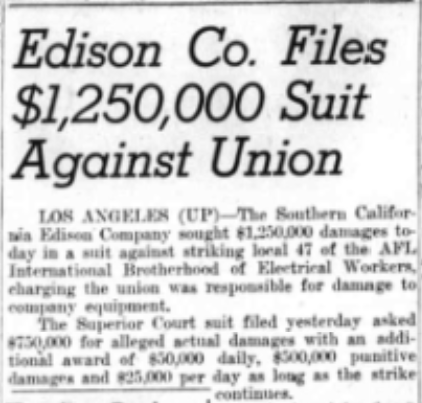

Edison then went on to sue the Edison workers’ union.

The citrus industry, although it was in decline, still existed.

Education

Fullerton’s growth involved the building of new schools opening, including Raymond Avenue Elementary School.

Fullerton Union High School’s mascot was the Indians. This included embarrassing cultural appropriation that involved “Pow Wow” events.

The News-Tribune often referred to FUHS sports teams not as the Indians but as the much more offensive “Redskins”.

In the context of the Cold War, teachers had to take oaths that they were not communists.

Annexation Fights

Part of Fullerton’s growth involved fights with other local cities over annexation of unincorporated land, specifically Brea and La Habra.

The issue ultimately went to court (stay tuned)!

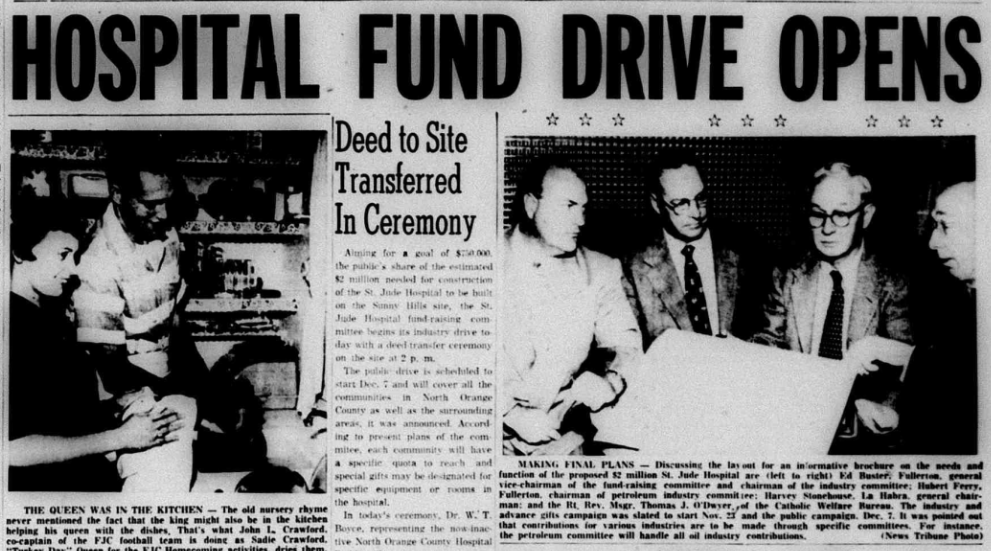

The Origin of St. Jude Hospital

Fullerton’s growth meant that its old hospital was inadequate to meet the needs of a rapidly growing community.

It was decided that a new, much larger, hospital needed to be built, and so local groups worked to acquire the land on the former Sunny Hills Ranch that would eventually become St. Jude Hospital.

Thus began a massive local fundraising drive for the construction of St. Jude.

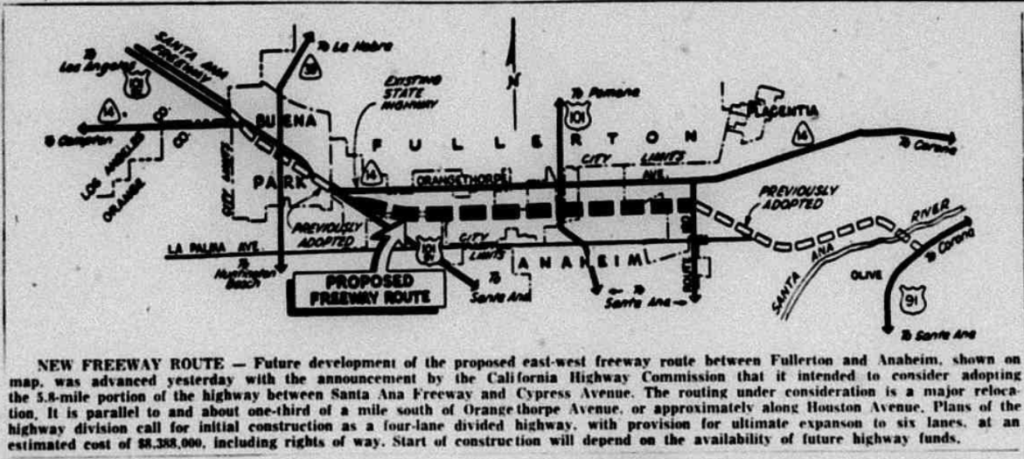

Transportation

In the first half of the 20th century, Southern California had the largest inter-urban rail system in the world–the Pacific Electric “Red Cars.” In 1953, a new corporate conglomerate purchased the financially ailing Pacific Electric, and eventually dismantled this rail system.

The future of Southern California would not be trains, but cars! The future was freeways!

The decline of the Red Cars, a tragedy in my opinion, is part of the plot of the 1989 film “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?”

Government and Politics

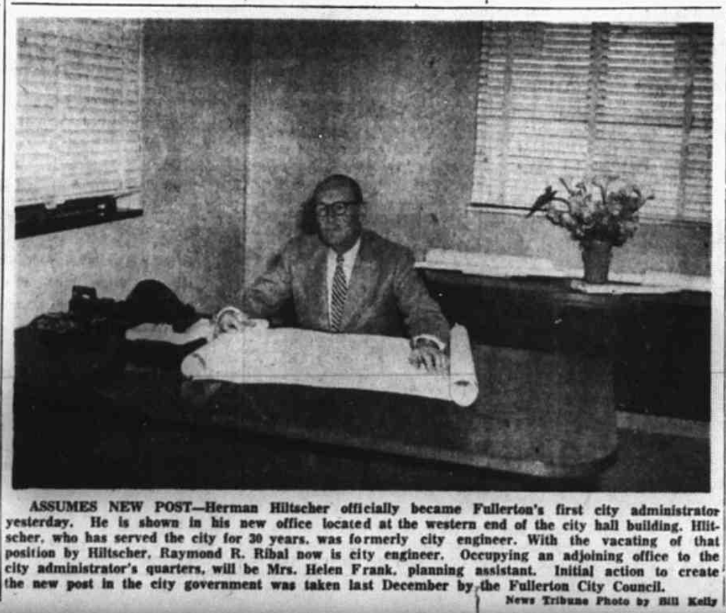

In 1953, Fullerton made a major change in its system of governance by creating the position of City Administrator (now called City Manager). This unelected bureaucrat would now (arguably) have as much power to create policy as the former City Council.

Fullerton’s first City Administrator was alleged former Klansman Herman Hiltscher.

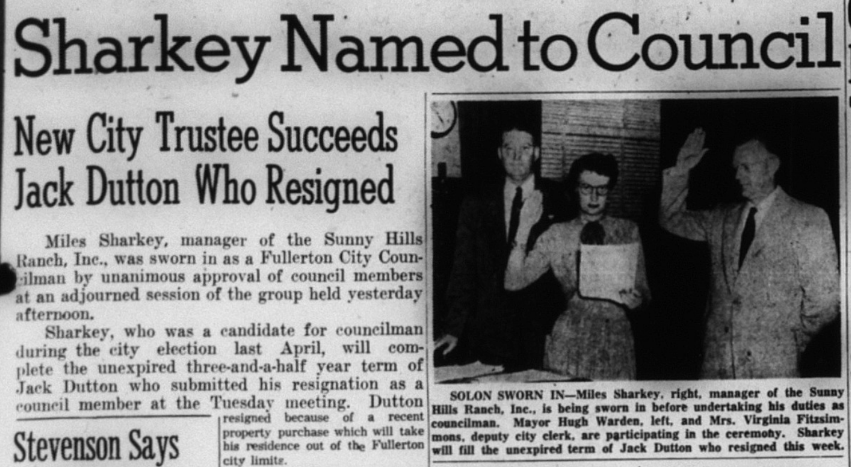

City Councilman Miles Sharkey (manager of the Sunny Hills Ranch company, who had been appointed, not elected) resigned because he no longer lived within the city limits of Fullerton and perhaps because he stood to gain financially by a proposed annexation of land north of Fullerton. The person who was appointed to replace him was Phillip Twombly.

Twombly, whose family moved to Fullerton in 1893, was the manager of Golden Citrus Juices, Inc. He had previously served as president of the Placentia Farm Bureau and director of the Orange County Farm Bureau.

Phillip Twombly is a fascinating figure because he would allegedly become involved in the JFK assasination.

Culture and Entertainment

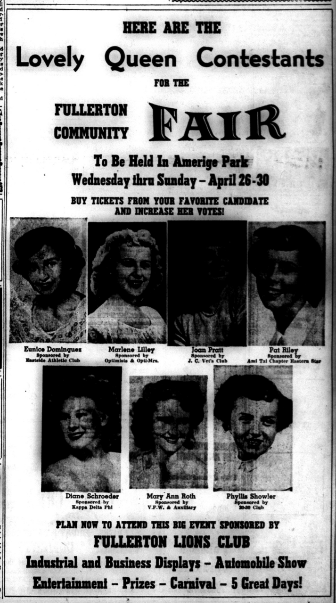

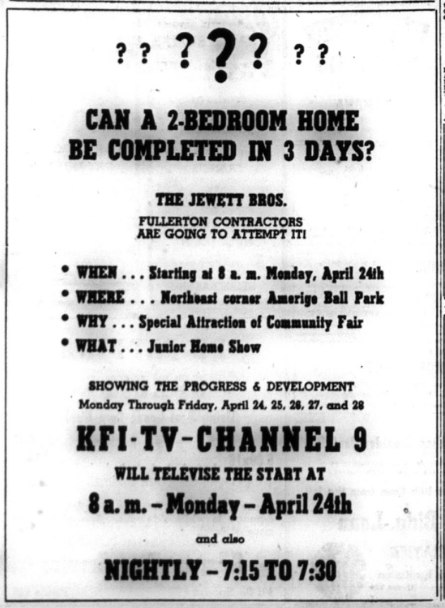

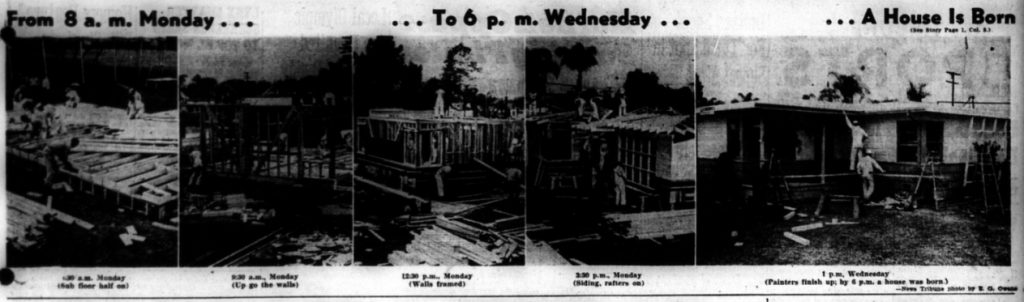

For culture and entertainment, Fullertonians attended an annual Community Fair.

The annual high school Homecoming was a large community event.

Local African American poet Ruby Berkeley Goodwin was honored.

And Fullerton hosted an annual Arkansas reunion.

Miscellaneous

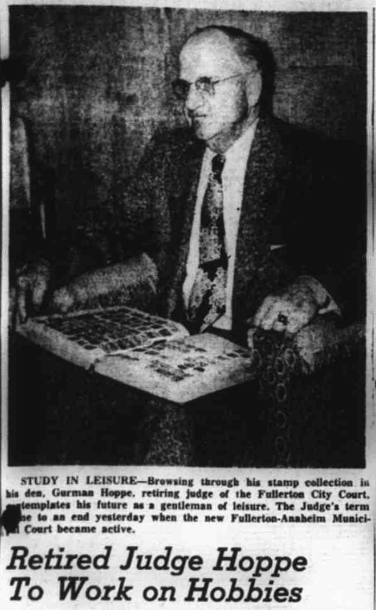

Fullerton’s City Judge since 1948, local business man since 1920 Gurman Hoppe retired. Hoppe came to Fullerton in 1912 and worked for the Stern and Goodman department store. In 1927 he went into business for himself, running Hoppe’s Hardware store at 104 and 106 S. Spadra road.

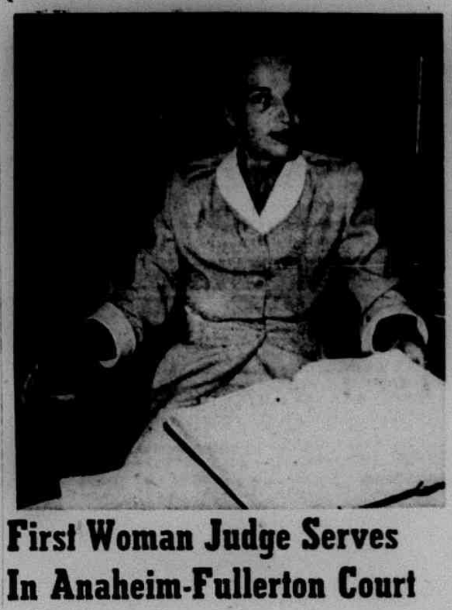

Cena Young was appointed as the first woman judge in a local court.

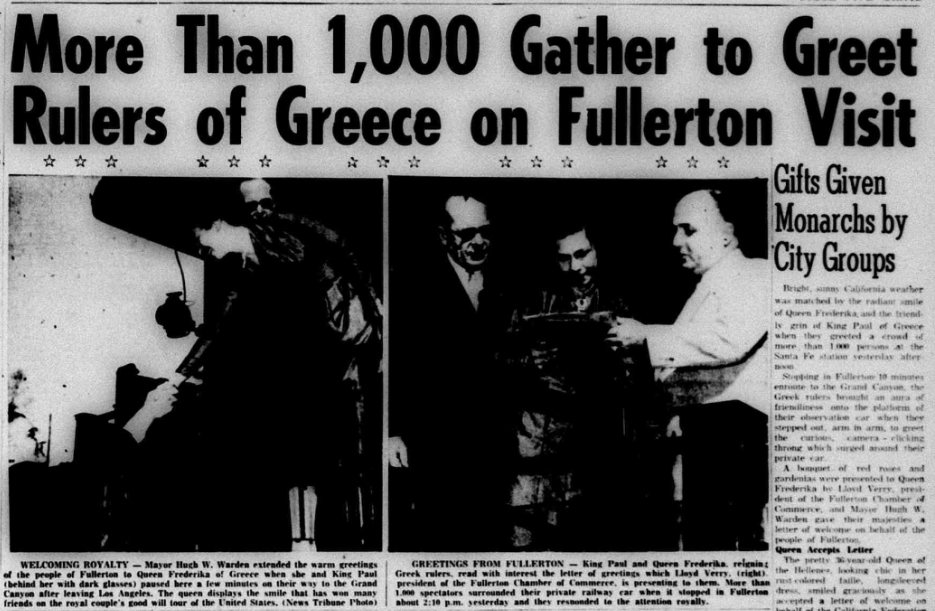

Over 1000 people gathered to greet the ruler of Greece when his train stopped briefly in Fullerton.

Deaths

Local drug store owner Jess Hardy died.

Long time resident Dr. F.H. Gobar died.

Stay tuned for top news stories from 1954!

-

Doss v. Bernal: Fighting Housing Segregation in Fullerton

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Today, when Americans think about the term “segregation” they are probably thinking about the South–where segregation was loudly and publicly enforced until it became officially illegal (though unofficially still practiced) through various court cases and Civil Rights legislation.

Many Americans are probably not as aware that housing and school segregation actually extended far beyond the south and affected every part of the United States. In the North and out West, segregation was kept quieter, but it was pervasive.

By the 1920s, the most common method for enforcing residential segregation was something called “racially restrictive covenants.” These were agreements on the deeds of housing that prevented non-whites from renting or purchasing those homes. These covenants were standard practice among developers and realtors all over the US including in Fullerton, California–the subject of my research.

Because of these covenants, for the first half of the 20th century, most neighborhoods in Fullerton were off-limits to people who weren’t white. Mexican-Americans, by far the largest minority group, were confined to agricultural work camps or carefully proscribed “barrios.”

However, in 1943, a Mexican American family in Fullerton–Alex and Esther Bernal–challenged this widespread practice, and won. The legal case was called Doss v. Bernal.

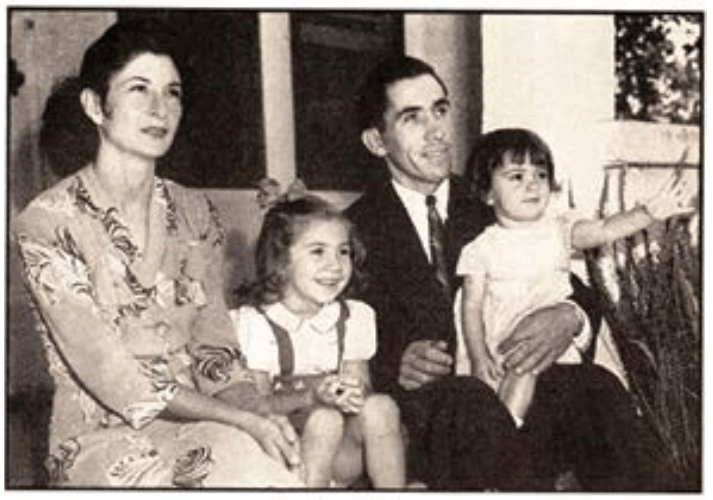

The Bernal family, 1943. Photo courtesy of Time magazine. “Doss v. Bernal successfully challenged the residential segregation of Mexican Americans in Orange County, resulting in one of the earliest legal victories against racial housing covenants in the United States,” Robert Chao Romero and Luis Fernandez write in “Doss v. Bernal: Ending Mexican Apartheid in Orange County.”

This case preceded by five years the more well-known (at least among civil rights lawyers) Shelly v. Kraemer (1948), a Supreme Court case which declared racially restrictive covenants legally unenforceable.

Born in Corona, Alex Bernal was raised in Fullerton’s Truslow barrio. He married Esther Munoz De Anda in 1937 and the couple had two children, Irene and Maria Teresa. Alex worked as a produce truck driver. To accommodate their growing family, the Bernals decided to purchase a white stucco home at 200 E. Ash in a neighborhood called the Sunnyside Addition, near but outside the Truslow barrio.

Unbeknownst to the Bernals, this house, like all the others in the Sunnyside Addition, had a racially restrictive covenant which stated “That no portion of the said property shall at any time be used, leased, owned or occupied by any Mexicans or persons other than of the Caucasian race.”

Despite this restriction, the owners Joe and Velda Johnson sold the property to the Bernals, and the family moved into their new home–happily following their American dream.

“For many Mexican Americans, suburban homeownership symbolized a chance towards upward mobility,” Shannon Anderson writes in Remembering the Bernals: Untangling the Relationship Between Race, Space, and Public Memory in Fullerton, California. “Additionally, suburbanization allowed Mexican Americans to stake their claim to permanent American identity in defiance of the stereotype that all people of Mexican descent were migratory, temporary residents.”

But their white neighbors were not so happy.

“Within a week of living on East Ash Avenue, the Bernals returned home one evening to find that someone had broken into their new home and thrown all their possessions into the street,” Anderson writes. “In a separate incident, Esther answered the door to a man who described himself as an officer of the law. In a ‘vulgar manner,’ he told Esther that she and Alex should move out of their new house because the white residents didn’t want Mexicans living in their neighborhood.”

When this harassment failed to get the Bernals to move, all the neighbors signed a petition saying they wanted the Bernals out. When that didn’t work, some of their neighbors (the Dosses, Shrunks, and Hobsons) filed a lawsuit in the OC Superior Court “on behalf of a majority of all the other lot owners” of the Sunnyside Addition requesting legal enforcement of the racially restrictive housing covenant.

The neighbor’s legal complaint is a clear expression of the racist social attitudes of the time:

“The permitting of Mexicans and other races to live in and to use and occupy the residence buildings in said tract, would necessitate coming in contact with said other races, including Mexicans in a social and neighborhood manner, and that if said race and Mexican Residential use and restriction in said tract of land is broken, other Mexicans and persons of other races will soon move in and occupy residences in said Restricted residential district, and that the value of said residential property therein will be greatly depreciated…and for further reasons that such breach of said restrictions and conditions will greatly lower the social living standard.”

After being served this legal complaint, the Bernals still refused to leave. Instead, they hired lawyer David Marcus to defend their rights. Marcus, a Jewish lawyer who was married to a Mexican woman, would go on to represent Orange County Mexican American families fighting school segregation in the landmark 1947 case Mendez et al v. Westminster.

The first judge assigned to the Bernal’s case, Justice Morrison of Orange County, tried to issue a ruling against the Bernals before the case even went to trial. Marcus successfully petitioned to have an outside judge, Albert F. Ross, brought all the way down from Shasta County in northern California to hear the case.

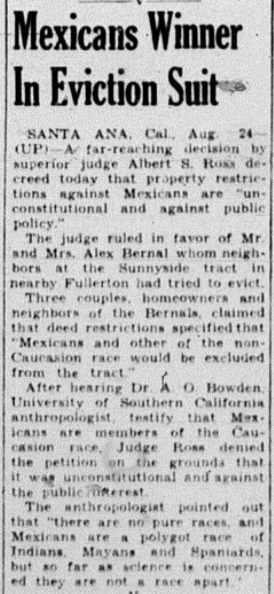

The Doss v. Bernal trial took place in late August, 1943 in the Old Orange County courthouse in Santa Ana.

One of the central points of contention in the trial was whether the Bernals, and by extension all Mexican Americans, were “white.” Race is, of course, a social construct, not a biologically meaningful concept. It was meaningful insofar as it could be weaponized to exclude people like the Bernals. The plaintiffs’ lawyer Gus Hagenstein tried to prove that Mexican Americans were a part of a distinct race (not white), and Marcus argued that the Bernals should be classified as white. Both sides brought in anthropologists to try to sort this out.

One anthropologist explained that there were three types of races: European, Negroid, and Mongoloid, and that because the Bernals were neither Negroid or Mongoloid, they were more akin to European, and therefore white.

This whole discussion of race ends up sounding pretty silly in retrospect, but it did have repercussions because, according to this “race” argument–covenants that excluded African Americans and Asians could still be considered valid.

Hagenstein also claimed that the presence of Mexican-Americans in suburban neighborhoods would do “irreparable damage” to property values. He brought in real estate professionals, including former Fullerton Mayor Harry Crooke, to attest to this. Marcus sought to refute harmful stereotypes of Mexican Americans in an attempt to show that the Bernals were respectable people who would not be a detriment to their neighbors or bring down property values.

When you really drill down into the logic behind these covenants, they turn out to be based mostly on fear, scientifically dubious ideas about race, and negative stereotypes. What they were mostly about was preserving white supremacy.

The arguments in the Bernal case that would have the most lasting significance had to do with Constitutional rights.

“Marcus cited the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution, which maintain that no one can be ‘deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.’ Unbeknownst to Marcus, this would be the first time that these amendments were successfully invoked in a lawsuit regarding racialized housing discrimination, beginning a trend in subsequent civil rights cases,” Anderson writes.

It was not lost on Marcus that this trial was taking place during World War II, when the United States was fighting against the racist and fascist Nazi Germany in defense of liberty and democracy. Some local Mexican American soldiers even attended the trial in a show of support for the Bernal family.

After a four-day trial, Judge Ross ruled in favor of the Bernals, declaring the racially restrictive covenant “null and void.” He further stated that such covenants were “injurious to the public good and society; violative of the fundamental form and concepts of democratic principles.” He agreed that the covenant violated the 5th and 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Despite the historic importance of this ruling, it’s interesting that the local press (the Fullerton News-Tribune) barely mentioned the case, devoting just two small articles to it. Neither the Orange County Register nor the Los Angeles Times even mentioned the case.

One of two small articles on Doss v. Bernal published in the Fullerton News-Tribune. But other news outlets were paying attention. The Bernals got their picture in Time magazine, along with a story about their legal victory, and were even featured in the radio program “March of Time.”

An African American newspaper in Los Angeles, the California Eagle, featured the Bernal story prominently on the front page with headlines like “Race Property Bars Held Illegal!” and “Santa Ana Judge Says Restrictions No Good!”

California Eagle headlines from 1943. Mexican Consul Manuel Aguilar was also paying attention, stating: “We consider any restriction on the rights of Mexicans to live where they please against the Good Neighbor Policy and against the Constitution of the United States.”

Interestingly, “One of the most detailed accounts of the Bernals’ trial comes from the San Antonio, Spanish-language newspaper, La Prensa,” Anderson writes. “Running on multiple pages, ‘Decision en Favor de Una Familia Mexicana Que Reside en Fullerton, California’ details the legal proceedings, including additional statements from Marcus and quotes from Ross’s ruling and subsequent lecture.”

Doss v. Bernal set legal precedent that would eventually lead to the 1948 Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer, which ruled that racially restrictive covenants were legally unenforceable.

But it would be wrong to conclude that Doss v. Bernal ended housing discrimination and segregation in Fullerton or elsewhere.

“Although the outcome of Doss v. Bernal set legal precedent in determining that Mexican Americans are white and racialized housing covenants are unconstitutional, this ruling was not widely enforced in Orange County,” Anderson writes. “Rather, residential space would remain racialized within the region, with instances of racialized housing discrimination against nonwhite individuals cropping up in the decades to come.”

The fact of lingering housing discrimination is perhaps best represented by the fact that in 1964 (21 years after Doss v. Bernal), a majority of California voters passed Proposition 14, which sought to overturn the state’s Rumford Fair Housing Act. This action was later declared unconstitutional, but it sent a strong signal that a majority of white property owners were just fine with housing discrimination.

In a case of history repeating itself, Alex and Esther’s daughter Irene experienced housing discrimination in the 1960s “when she tried to rent an apartment in Fullerton and was refused by the landlord,” Anderson writes. “However, her husband, who was white, had no problem when he applied to rent out the same apartment.”

And although they won, the case was also devastating for the Bernal family.

“Alex and Esther no longer felt safe in their home…the Bernals were concerned that their newfound exposure would result in additional, ramped-up harassment,” Anderson writes. “Thus, the Bernals never got the chance to live in the home that they fought so hard for. Instead, the family of four moved into Alex’s parents’ house. After all that happened, the Bernals ended up back on Truslow Avenue—Fullerton’s segregated barrio designated for residents of color.”

Two years after the trial, Esther Bernal died of cancer at age 29. The stress of the trial likely exacerbated her declining health.

For a while after the trial, the Bernals received dozens of letters of support from all over the United States.

But as time went on, the thing that disappeared in Fullerton was not housing segregation, but public memory of the Doss v. Bernal case.

The case is not mentioned in the two “official” Fullerton history books: Ostrich Eggs for Breakfast by Dora Mae Sim and Fullerton: A Pictorial History by Bob Ziebell.

Even Alex Bernal himself seemed to want to forget, rarely discussing the case, and putting all the letters, clippings, and court files into a box and storing it away for decades.

For nearly 70 years, the Doss v. Bernal case fell out of public memory, sort of like the Pastoral California mural on the side off the high school auditorium, which had been painted over for nearly 60 years.

It was not until 2010 that an intrepid reporter for OC Weekly named Gustavo Arellano and a CSUF grad student named Luis Fernandez re-discovered the story and brought it back into public memory.

In a remarkable piece of local history reporting, Arellano’s “Mi Casa Es Mi Casa: How Fullerton produce-truck driver Alex Bernal helped change the course of American civil rights” re-introduced Orange County to Doss v. Bernal.

For his article, Arellano interviewed Bernal family members, pored through Alex’s box of old letters and files, and unearthed old news stories about the case.

Fernandez would go on to co-author an excellent 2012 article for UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center, entitled “Doss v. Bernal: Ending Mexican Apartheid in Orange County.”

The story of Doss v. Bernal was featured in a 2022 book entitled A People’s Guide to Orange County by Gustavo Arellano, Elaine Lewinnek, and Thuy Vo Dang.

In 2023, CSUF graduate student Shannon Anderson wrote a Master’s thesis entitled Remembering the Bernals: Untangling the Relationship Between Race, Space, and Public Memory in Fullerton, California. Her study highlights omissions in previous narratives, like the role of Esther Bernal in purchasing the house, and her deposition during the trial.

That same year, the Orange County Hispanic Bar Association (OCHBA) hosted a live reenactment of the Doss v. Bernal trial.

Anderson describes how in some cases, popular retellings have oversimplified the Bernal story into one of total victory, of having ended housing discrimination and segregation.

A 2023 article in the Fullerton Observer, reporting on the reenactment of the trial, was titled “A Reenactment of the 1943 Historical Trial that ended housing discrimination.”

“The issue with this is that the Bernals’ trial did not immediately put an end to housing discrimination. Although the case set legal precedent that would eventually go on to influence Supreme Court cases, racist housing practices would not be solved, but rather reified over the decades,” Anderson writes. “Also, the Bernal family suffered immensely from their experience with racialized exclusion.”

The problem with seeing the Bernal’s story as one of total victory is that it may prevent us from understanding how housing discrimination still persists.

“Perpetuating the idea that segregation is an issue of the past when it still exists, just in a different form, allows contemporary forms of racialized housing segregation to continue to operate without objection,” Anderson writes. “While racial segregation is no longer enforced on an institutional or legal level, de facto segregation continues to be upheld through longstanding cultural ideas, economic inequality, and social practices.”

A stark expression of this is the racial wealth gap. In 2019, the average income of a Caucasian household in the U.S. was about $188,200, while the average income of a Mexican American household was $36,100. This gap dictates which neighborhoods Mexican Americans and people of color can live in.

Rather than seeing Doss v. Bernal as something that ended housing discrimination and segregation, it is more accurate to see the case as part of a decades-long struggle of chipping away at the enduring effects of white supremacy.

There have been two attempts to commemorate the Bernal house as a historically significant property under the Mills Act, in 2010 and 2020, but both attempts were unsuccessful.

“Commemoration of the site would require Fullerton to come to terms with its shameful, racist past,” Anderson writes.

Sources:

“Mi Casa Es Mi Casa: How Fullerton produce-truck driver Alex Bernal helped change the course of American civil rights” by Gustavo Arellano, OC Weekly, 2010.

“Doss v. Bernal: Ending Mexican Apertheid in Orange County” by Robert Chao Romero and Luis Fernando Fernandez published by the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center in 2012.

Remembering the Bernals: Untangling the Relationship Between Race, Space, and Public Memory in Fullerton, California. CSUF Master’s Thesis by Shannon Anderson, 2023.

A People’s Guide to Orange County. Lewinnek, Elaine, Gustavo Arellano, and Thuy Vo Dang. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2022.

-

Fullerton in 1952

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library has microfilm from the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune newspaper stretching back to 1893. I am in the process of reading over the microfilm, year by year, to get a sense of what was happening in the town over the years, and creating a mini archive. Below are some news stories from 1952.

In international news, the Korean War raged on. Some local boys were drafted to fight, and sometimes die, in this early Cold War conflict.

The British Empire was still a thing.

The US Congress passed the McCarran-Walter Immigration Bill, which modified but still kept the racist restrictions that were first codified in the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, and added new grounds for restricting and deporting immigrants who were thought to be “subversive”–this was in the context of the Cold War Red Scare.

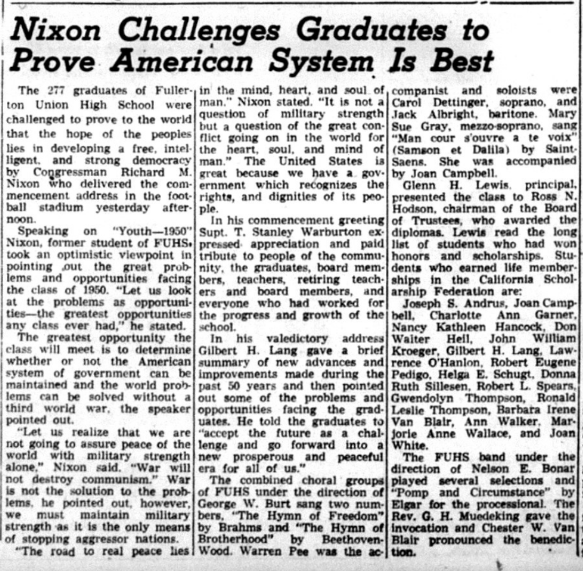

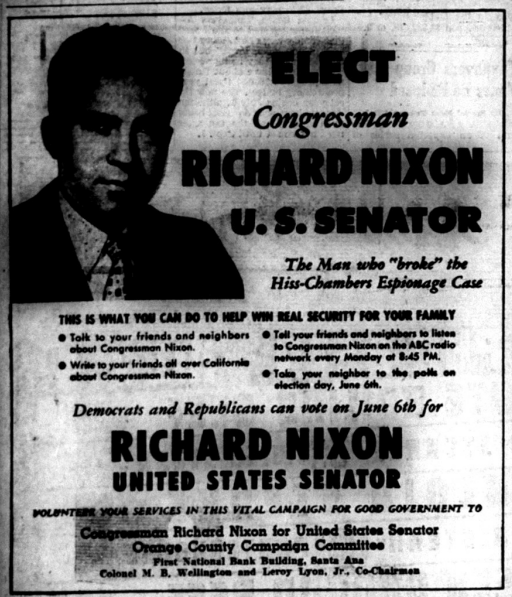

Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected president, and his Vice President was local boy Richard Nixon, who was born in Yorba Linda and attended Fullerton High School.

While Nixon is mostly remembered for the Watergate scandal, he first rose to power as a McCarthy-style Red Scarer. He was a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee, and famously investigated alleged communist spy Alger Hiss.

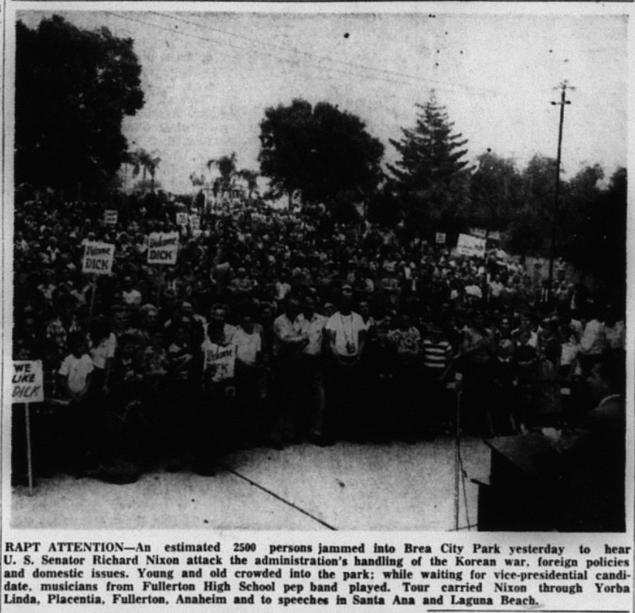

While running for Vice-President, Nixon held a number of campaign rallies in Orange County.

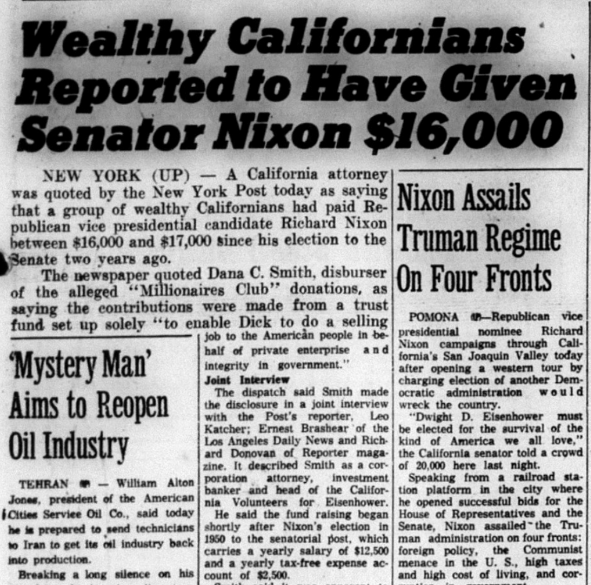

Six weeks before the 1952 presidential election, it was reported that Nixon had received between $16,000 and $18,000 (approximately $220,000 in 2025 dollars) not in campaign contributions, but directly from a fund bankrolled by a group of 76 wealthy Californians.

Dana C. Smith, disburser of the alleged “Millionaires Club” donations, told the New York Post that the contributions were made from a trust fund set up solely “to enable Dick to do a selling job to the American people in behalf of private enterprise and integrity in government.”

While Nixon called the story a “smear” from his opponents, he didn’t deny the fund, and this led to accusations of corruption. It was a major scandal.

Nixon said that, by taking the private funds, he was “saving you taxpayers money.”

Eisenhower and Nixon’s Democratic opponent Adlai Stevenson said the questions that arose were: “Who gave the money, was it given to influence the Senator’s position on public questions: and have any laws been violated?”

This was particularly embarrassing to the Eisenhower campaign, which was railing against “corruption” in government.

For a while, it was uncertain if Nixon would remain on the Eisenhower ticket. But then the Republican National Committee paid $75,000 (nearly a million dollars today) for a 30-minute televised speech by Nixon on September 23, 1952 in which he defended himself. This became known as the “Checkers Speech.”

The “Checkers Speech” (which you can watch HERE) is particularly infuriating because it’s an early example of a politician using an emotional appeal to a televised audience of around 60 million Americans to evade real accountability.

In the speech, Nixon claimed to give a full accounting of his personal finances, but what he actually did was give the impression that he was a public servant of modest means. He said that one gift he received was a cocker spaniel dog which his daughters named Checkers and that they were going to keep the gift.

What Nixon did NOT do was name the 76 wealthy Californians who had contributed to the fund, which would have enabled any reporter to have investigated whether he used his power as a congressman to benefit them. The full list of donors has never been made public.

And yet, somehow, the “Checkers Speech” worked.

Some notable Fullertonians told the Fullerton News-Tribune that they felt his speech had exonerated the candidate (it had not).

R.S. Gregory said, “Nixon is absolutely all right. He made a clear statement of his affairs. I think he is in the right.”

Verne Wilkinson said, “The speech was outstanding. He certainly redeemed himself, in fact, in my opinion he was above reproach in the first place.”

H.H. Kohlenberger said, “It was an excellent presentation which, in my opinion gained many votes for Nixon, and which was unprecedented in political history.”

And so, rhetoric won over substance, and Eisenhower and Nixon won.

Local Politics and Government

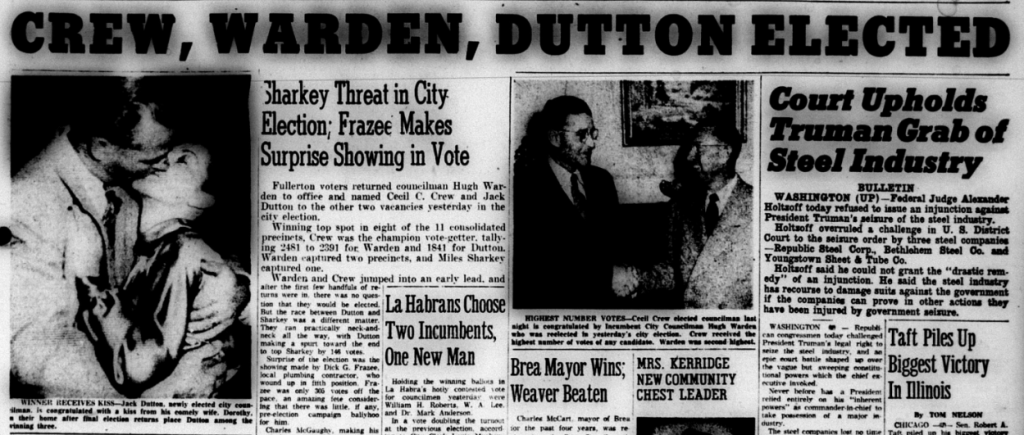

In local political news, Cecil Crew (car dealership owner), Hugh Warden (a roofing contractor), and Jack Dutton (owner of a salvage business) were elected to City Council. Warden was named mayor.

Not long after the election, Jack Adams (who had been elected previously) resigned from council, and Irvin Chapman (son of citrus grower Charles Chapman) was appointed to fill his seat.

This prompted protests from some Fullertonians, who argued that Chapman had lost the last time he ran for council, and should therefore not be appointed.

“I believe the voters showed two years ago, beyond all doubt, that they did not want Chapman on the City Council!” a reader wrote in a letter to the editor of the Fullerton News-Tribune. “I believe it is a little-disputed fact that the incumbent always has the edge in an election, yet two generally unknown men came in ahead of the then-incumbent Irvin Chapman. There are going to be a lot of very unhappy voters if he is permitted to sneak in the back door after that had showed him out the front—they thought!”

Councilmember Kermit Wood strongly objected to Chapman’s appointment.

“With the help of his cohorts, the mayor has held the back door open for another councilman of his choosing,” Wood said. “No consideration has been given the voters of Fullerton. I charge that the action taken by the three councilmen is unethical and dictatorial and not in the best interests of the people of Fullerton…Such is the fiber of dictatorship and communism. Never in the annals of Fullerton has this flagrant disrespect for the right of the people and for decency and fairness been equaled.”

Lots of folks showed up to a City Council meeting urging that Chapman not be appointed. However, their pleas were unsuccessful. He was appointed.

“Kenneth Harris acted as spokesman of the opposition and demanded that Mayor Warden rescind the council action, backing up his demand with a petition signed by approximately 300 persons,” the News-Tribune reported.

Not long after this, newly elected councilman Jack Dutton also resigned, and was replaced by Miles Sharkey, manager of the vast Sunny Hills Ranch property.

Thus, two of the three elected representatives were replaced by appointed ones–owners or managers of valuable large tracts of land. This did not bode well for truly democratic representation.

In another somewhat anti-democratic move, the new Council considered fundamentally changing the structure of local government by creating a new position of City Administrator (now called City Manager). This would be another appointed position. They chose long time city employee (and alleged former Klansman) Herman Hiltscher.

The stated reason for the change was that City Councilmembers did not have the time to oversee such a large and growing city, and thus required a full-time administrator. This makes sense in theory, but in practice it raised questions about true democratic governance for cities.

One of the few academic books focusing on Orange County is Postsuburban California: The Transformation of Orange County Since World War II. This book contains various articles written by historians and social scientists.

In a chapter entitled “Intraclass Conflicts and the Politics of a Fragmented Region,” UCI historian Spencer Olin describes the implications of a move to a Council-Manager system: “By the mid-1960s, then, several marked changes in political structures and practices had occurred that clearly favored the interests of a certain class segment, first of regional capitalists and next of owners of national and international corporations…an increased depoliticization of the municipal administration had taken place through the imposition of the council-manager system and the move away from elected officials toward appointed ones.”

This change happened in a number of Orange County cities in the mid-20th century, and it is currently the dominant model for many cities.

Olin continues: “If we carefully analyze the political forces behind such changes in municipal (city) government, while at the same time paying attention to underlying economic developments, we can uncover the antidemocratic implications of suburban policies…We can see, for example, that important areas of public authority were removed from the control of locally elected officials and were taken over by relatively autonomous and distant governmental agencies largely insulated from the political process.”

It is notable that the very year Fullerton sought to impose the Council-Manager system, two elected City Councilmen resigned and were replaced by unelected appointees who were just the sort of “regional capitalists” Olin describes: Irvin Chapman (of the wealthy, landowning Chapman family), and Miles Sharkey (manager of the vast Sunny Hills properties).

Land use decisions by the City Administrator and the newly-configured council would stand to benefit large landowners, especially as the city was undergoing a transformation from agriculture to suburban, commercial, and industrial development.

Even before he became City Administrator, Hiltscher was city engineer. According to the News-Tribune, “All recent subdividing throughout the community has been controlled by standards set by the engineering office under Hiltscher’s management, which has brought Fullerton to be known as ‘The City of Beautiful Homes.’”

In the “City of Beautiful Homes” those who owned (or managed) a lot of land stood to make a fortune. Two of these men were Chapman and Sharkey.

Others elected in 1952 included Leroy Lyon, John Murdy, and Ralph McFadden.

The Red Scare

As the Cold War ramped up, so did the Red Scare. Richard Nixon’s anti-communist activities was part of what made him popular locally among a generally conservative community.

Fullerton local William Wheeler took part in the House Un-American Activities Committee probe of suspected communists.

A Fullerton lawyer named David Aaron testified that he had been a communist in the late 1940s while serving on the National Labor Relations Board.

“Aaron said he joined the party in 1946 when his NLRB job ended after two or three months,” the News-Tribune reported. “His contact with persons engaged in labor disputes before the board, Aaron said, caused him to decide ‘there must be something wrong with the economic system when all these things were happening.’”

One problem with the “Red Scare” was that it tended to silence legitimate critiques of the inequalities created by the capitalist system. It served to cement capitalism as the only allowable economic system in American discourse.

The Red Scare also weirdly associated homosexuality with communism, and many gay people were persecuted and lost their jobs.

Anti-communist crusaders like Fred Schwarz combined Christianity and conservative politics to paint the conflict between capitalism and communism as one of good vs. evil.

Probably the biggest real danger during the Cold War was the existence of atomic bombs. The US had developed the hydrogen bomb, which was many times more powerful than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.

The Russians were also developing atomic bombs in a perilous arms race. This prompted local programs like “Operation Skywatch” in which regular citizens would watch the skies for Russian bombers.

Growth

Fullerton continued its phenomenal post-war growth.

As Fullerton grew, many new housing subdivisions were being built.

The preferred type of housing in Fullerton was the single family home. Residents and local leaders, as they are today, were generally opposed to low-income housing, apartments, and trailer parks.

For example, the city voted to remove the low-cost veteran’s housing near Fullerton College, and on Truslow.

“City Planning Commission yesterday recommended that Fullerton high school and junior college district remove the veteran’s housing from North Harvard avenue on or before July 1, 1954,” the News-Tribune reported. “Two housing foes, one who called the establishment of the housing units ‘strictly a socialist measure,’ were present at the hearing to voice objections to the housing units being located on North Harvard avenue.”

Local realtors lobbied hard against any kind of “public housing.”

Some residents and neighbors were even opposed to allowing more dense housing like apartments.

And the City Council adopted a strict trailer park ordinance.

Building lower-cost housing was at odds with realtors, developers, and homeowners’ desire to maximize their property value–to the detriment of those less well off. This sentiment remains today, and has undoubtedly contributed to the present housing affordability crisis.

Along with increased residential development, Fullerton also saw increased industrial development as well. Northrop Aircraft built a large plant on Orangethorpe.

Beckman Instruments was planning to build a large facility just north of the city limits.

Hunt Foods in west Fullerton expanded their facilities.

In 1952, Hunt Foods, owned by Norton Simon, was the fourth largest company selling canned goods in the United States, with 12 facilities and an annual sales of over $60,000,000 (worth ten times that in 2025 dollars).

Part of what made Hunt’s successful was the power of acquisitions and branding. Simon would acquire smaller food canning companies and then bring them under the Hunt’s label.

The citrus industry was still large in the 1950s. The California Fruit Growers Exchange officially changed its name to Sunkist.

Oil was also still big business in Orange County, and offshore drilling was a new and controversial thing.

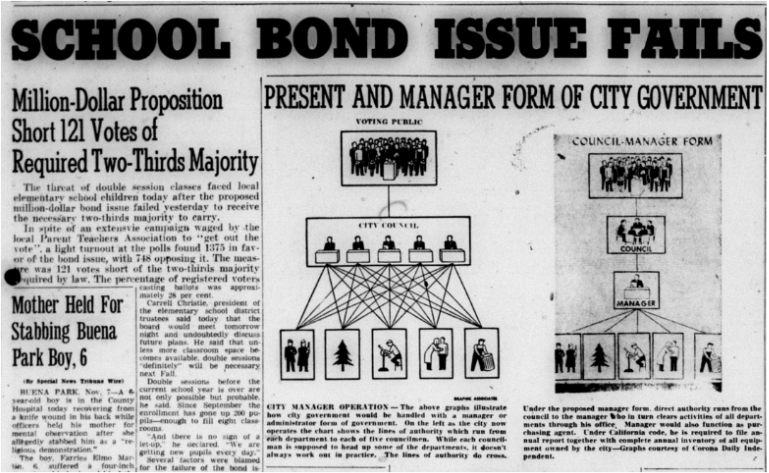

As the population grew, so did the need for new and larger schools.

Fullerton College purchased more land to expand its facilities.

As both Fullerton and Anaheim sought to expand, they agreed on a new boundary line separating the two towns.

Culture and Entertainment

For culture and entertainment, Fullertonians went to movies at the Fox Theater.

The city held a massive fair that drew thousands.

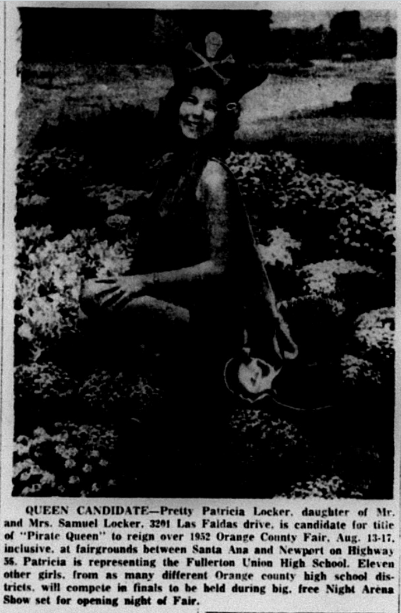

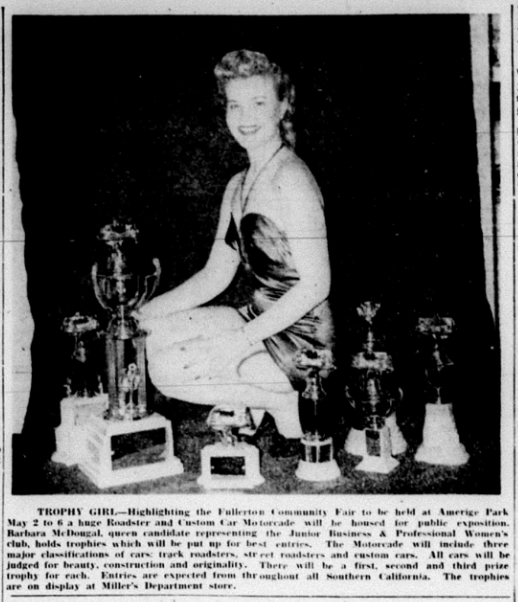

In the 1950s, it was a very popular thing to crown a “queen” for many community events. I think it had something to do with reinforcing normative gender roles.

Another popular fun spot was Knott’s Berry Farm and Ghost Town, which was not quite the theme park it is today, but still probably a good time.

Crime

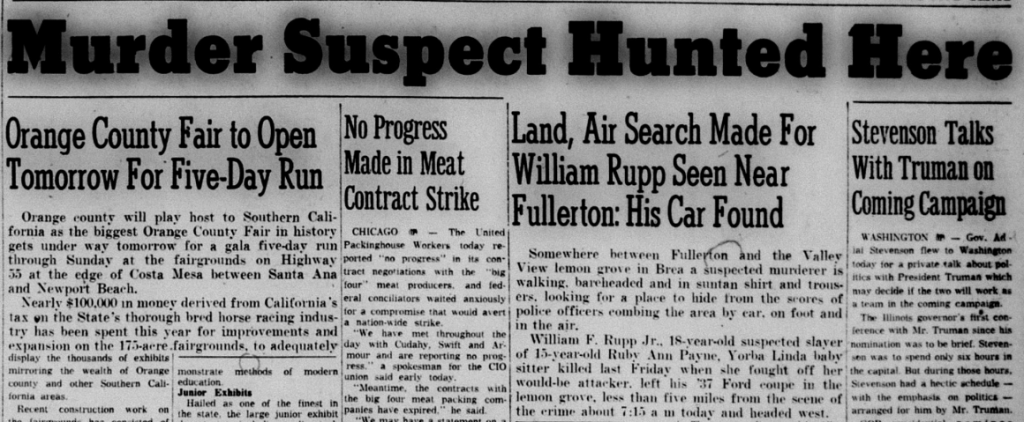

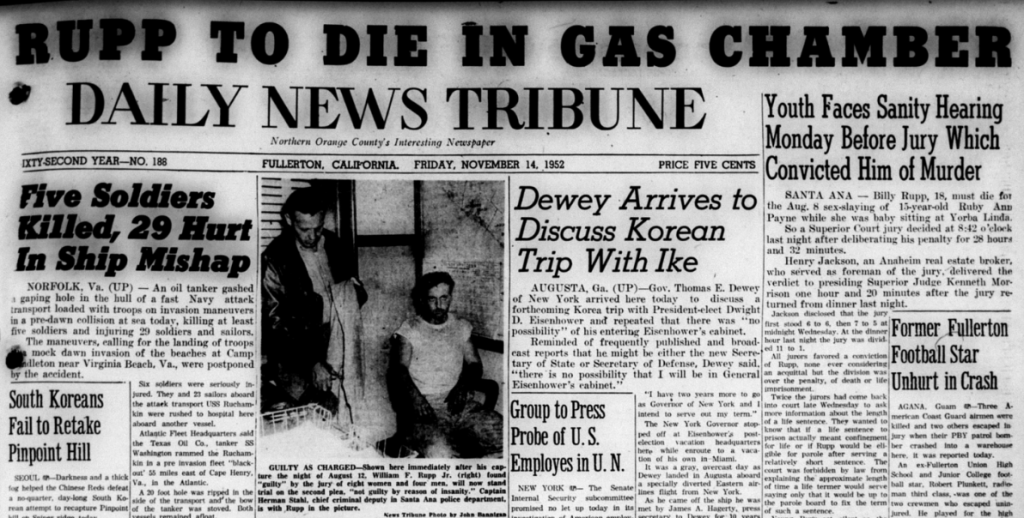

The highest profile local crime of 1952 was the murder of Ruby Ann Payne by William Rupp.

He was captured and arrested in a Brea Cafe, tried, and sentenced to death.

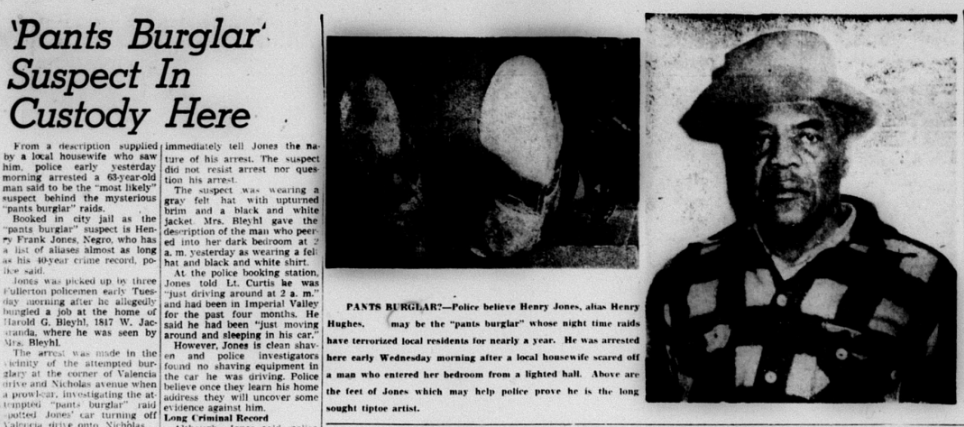

In less heinous crime news, the infamous “pants burglar” was finally captured.

Sports

Professional baseball teams like the Portland Beavers continued to train and play games at Amerige Park.

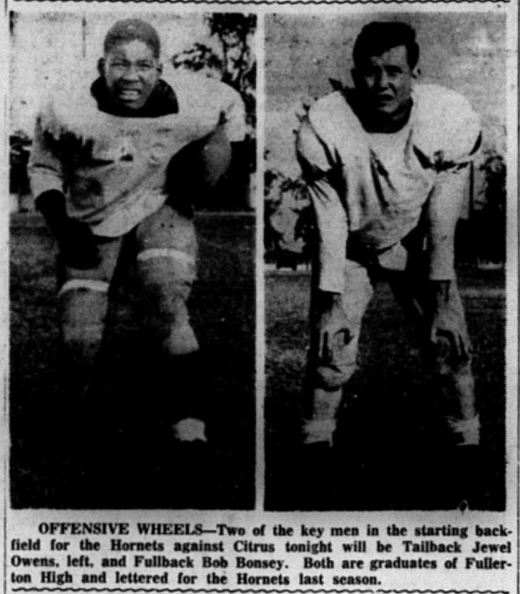

Here are a few more Fullerton sports stars:

Death

Pioneer rancher August Hiltscher passed away.

Stay tuned for top news stories from 1953!

-

Fullerton in the 1930s

The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Great Depression, Natural Disasters, and How the New Deal Benefited Fullerton

Following the stock market crash of 1929, the most significant problem facing Fullerton was the Great Depression.

Local groups like the American Legion operated a soup kitchen which offered food and (limited) lodging. Another soup kitchen was operated by the Maple School PTA.

In 1932, Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt defeated Republican Herbert Hoover in a landslide victory, becoming President of the United States. California, which had long been a Republican state, went blue for the first time in years, although a majority of Fullertonians voted for Hoover. The election was seen as a national repudiation of Hoover’s failure to improve the economic conditions of the Great Depression.

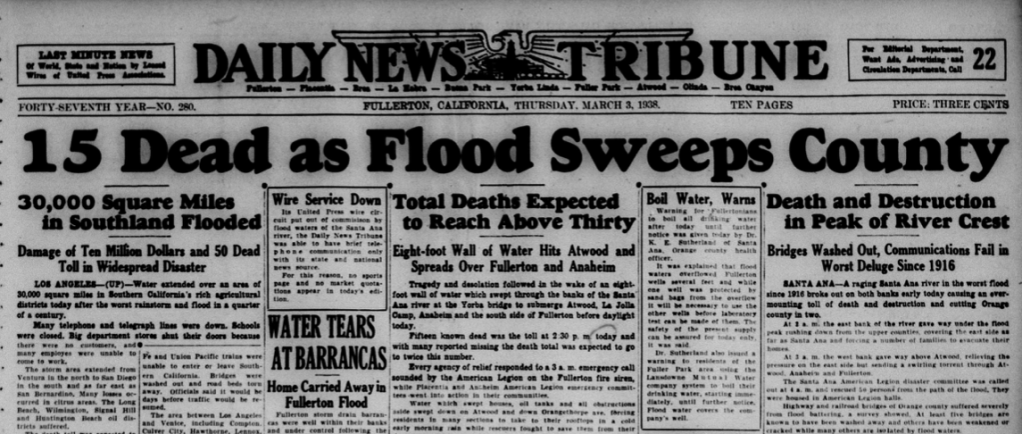

Fullerton Daily News-Tribune, 1932. Roosevelt’s first 100 days of office in 1933 were filled with sweeping legislation aimed at combating the Great Depression.

Roosevelt called it the New Deal. At the time, unemployment had reached 25 percent—the highest in US history so far. Federal programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) were created to give people jobs, and to simultaneously build up the country’s infrastructure—new roads, dams, parks, public buildings and more were built.

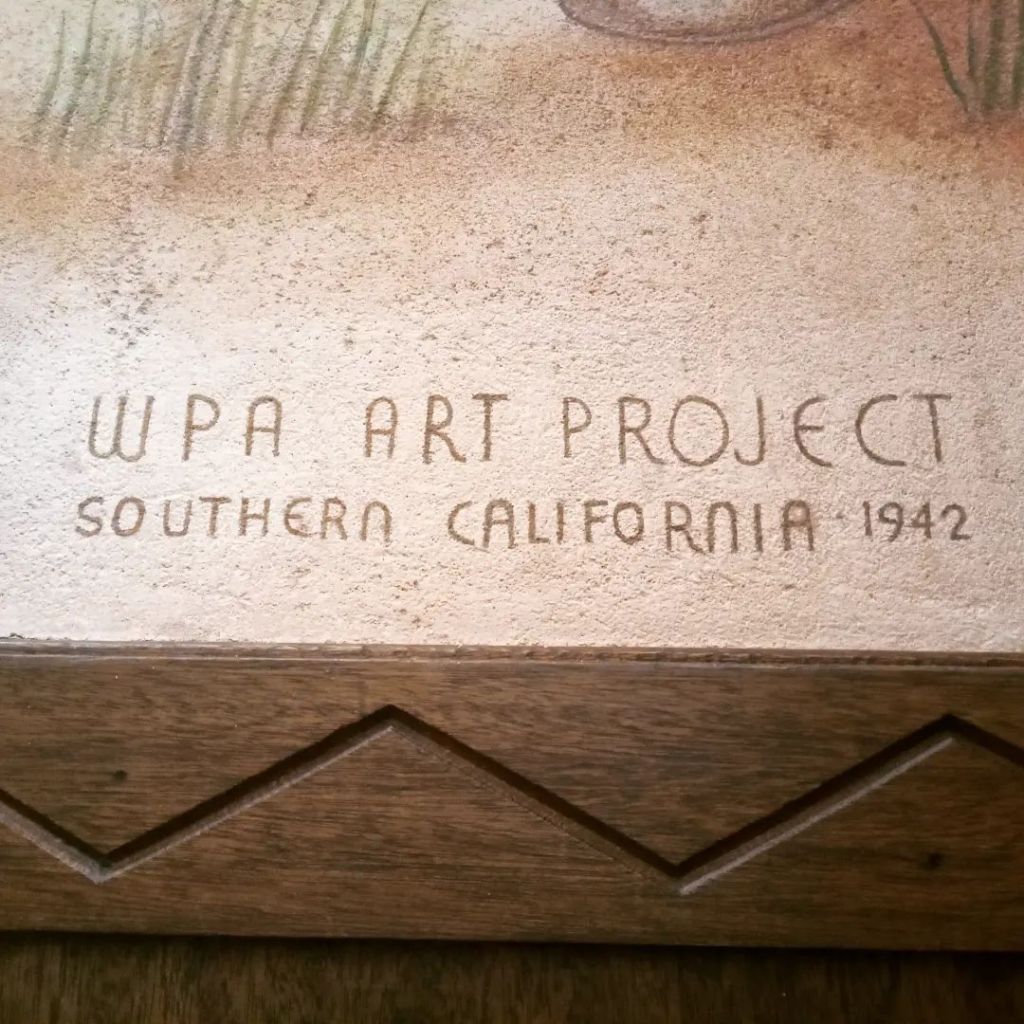

Works Progress Administration sign at Fullerton College. Photo by the author. The WPA alone gave over 8 million unemployed Americans jobs in its 8-year existence.

These government programs were not just for laborers. Artists, writers, actors, and musicians were also employed by the WPA to give folks not just jobs, but also hope and beauty in difficult times.

Today, nearly a century later, Roosevelt’s New Deal is primarily remembered in history textbooks and school curricula. But there is another way to remember its legacy—by recognizing the New Deal projects that still exist right where we live.

The city of Fullerton was a major recipient of New Deal funding and projects, many of which still exist today and have become some of the most iconic features of our local landscape. But first, a bit of context.

As if the Great Depression wasn’t hard enough to endure, Fullertonians also faced two major natural disasters during the 1930s.

First came the devastating Long Beach Earthquake of 1933, which caused over $50 million in damage and killed 120 people throughout the region, injured thousands, and caused tens of millions in property damage.

Fullerton Daily News-Tribune, 1933. Some refugees from the earthquake took up temporary residence in their cars at Hillcrest Park and at the American Legion hall, where they were provided food and shelter by local volunteers and the Red Cross. The Izaak Walton Lodge was also opened to those who had fled the quake.

“Fullerton American Legion members continued to feed more than 100 persons at each meal at the Legion hall,” the News-Tribune reported. “Many of this group are lodged in Fullerton homes or camping in the park and are nearly without funds, their homes demolished or unsafe for occupancy in Long Beach, Compton, Bellflower and other points.”

Mrs. Clarence Spencer on W. Orangethorpe took in 27 quake refugees.

Most Fullerton buildings escaped damage, although a chimney fell at the California Hotel, crashing through the roof of the cafe kitchen and half filling it with bricks and shattered building materials. Thankfully, no one was there at the time. The old elementary school on Wilshire and Lawrence (now a parking lot) also experienced some damage, causing it ultimately to be condemned.

Then came the 1938 flood.

Destruction in Fullerton from 1938 flood. The story of the flood is all the more tragic because local residents had twice voted down bonds that would have allowed for flood control infrastructure.

In 1931, Fullerton residents voted to enter the Metropolitan Water District, which would give the city access to water from the Colorado River via aqueduct. In 1933, the Orange County Water District was created.

In 1935, over six million dollars of federal funds (around $138 million today) were planned for a large scale Orange County flood control plan–to build the Prado Dam, as well as channelize much of the Santa Ana river. These federal dollars were contingent on local voters approving a bond measure to supplement the federal relief funds.

A well-funded opposition campaign which called the bonds a waste of taxpayer dollars resulted in the bond issue, and therefore the federal relief dollars, being lost. Voters actually had two chances to approve the bonds, but they voted them down twice.

Unfortunately, because the flood control measures were not passed, a few years later the 1938 flood would devastate local communities. It would take a natural disaster for people to understand the need to invest in this infrastructure.

In 1938, following severe rainstorms, the Santa Ana river overflowed its banks and caused widespread damage, killing over 50 people.

Fullerton Daily News-Tribune, 1938. “Water extended over an area of 30,000 square miles in Southern California’s rich agricultural districts today after the worst rainstorm and flood in a quarter of a century,” the News-Tribune reported.

Property damage was estimated at $10,000,000, and thousands were marooned by flood waters.

“Tragedy and desolation followed in the wake of an eight foot wall of water which swept through the banks of the Santa Ana river at the Yorba bridge to submerge Atwood [Placentia], La Jolla Camp, Anaheim and the south side of Fullerton,” the News-Tribune reported. “Water which swept houses, oil tanks and all obstructions aside swept down on Atwood and down Orangethorpe ave. forcing residents in many sections to take to their rooftops in a cold early morning rain while rescuers fought to save them from their dangerous quarters.”

The flood waters extended all the way to downtown Fullerton.

Local relief efforts were spearheaded by the Red Cross, local police and firefighters, and the American Legion. Shelters were set up in Hillcrest Park and St. Mary’s church for flood refugees.

Tragically, many of the victims of the flood were Mexican Americans living in citrus camps of south Fullerton, north Anaheim, and Placentia.

“Seven bodies were reported recovered at Atwood this morning. according to Chief of Police Gus Barnes at Placentia,” the News-Tribune reported. “Rescue workers with motorboats, rowboats and lifelines attempted to cross the river to the shattered cottages in which several hundred Mexican agricultural workers made their homes.”

The floods damaged or destroyed hundreds of homes, bridges, barrancas, and other infrastructure.

The 1930s were pretty rough.

“Because of these disasters, nearly every single community in Orange County was profoundly impacted by the New Deal,” Charles Epting writes in The New Deal in Orange County. “Dozens of schools, city halls, post offices, parks, libraries, and fire stations were built; roadways were improved, and thousands were given jobs.”

Out of the tragedies of the 1930s, here’s how the New Deal benefited Fullerton.

“With a population of just over 10,000 in 1930, Fullerton was one of the largest cities in Orange County at the time of the Great Depression. Relief projects were numerous. It is probable that Fullerton received more aid than any other Orange County city,” Epting writes. “What is also unique about Fullerton is that nearly all of its New Deal buildings are still standing and preserved as local landmarks.”

Maple School (244 E Valencia Dr): This school was retrofitted and expanded following the 1933 earthquake. It was partially funded by the Public Works Administration (PWA). It’s an example of Art Deco architecture. Plans were drawn by architect Everett E. Parks.

Entrance to Maple School. Photo by the author. Wilshire Junior High School (315 E Wilshire Ave): Originally constructed in 1921, it was reconstructed and expanded during the 1930s with PWA funds. The style is Deco/Greco. Now it’s the School of Continuing Education.

Wilshire School students circa 1930s. Photo courtesy of Fullerton Public Library Local History Room.

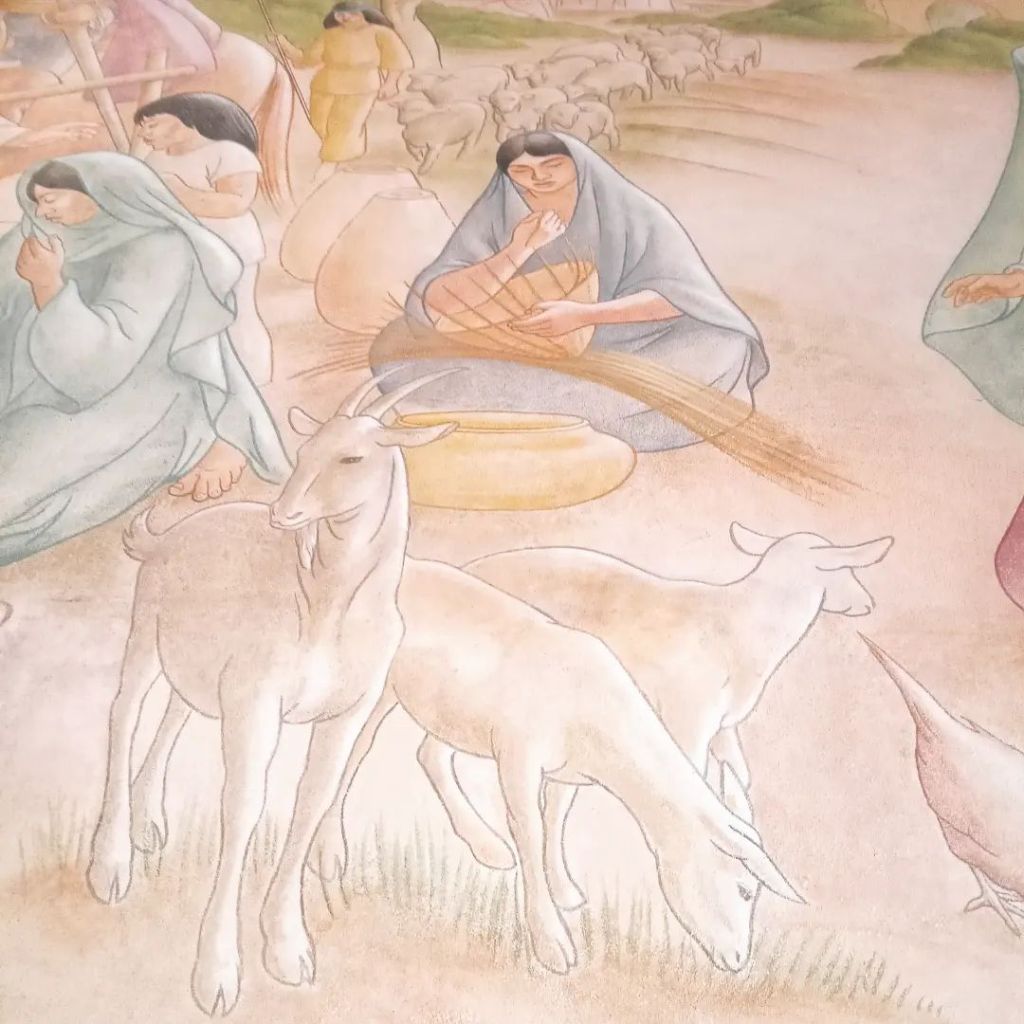

School of Continuing Education today. Photo by the author. “Pastoral California” mural on High School Auditorium (201 E Chapman Ave): Giant fresco painted by Charles Kassler under the Public Works of Art Project in 1934. Spanning 75 feet by 15 feet, the mural is unmatched in size and scope. One of the two largest frescoes commissioned during the New Deal. More on this later.

Portion of “Pastoral California” mural. Photo by the author. Fullerton College (321 E Chapman Ave): In 1935, Fullerton architect Harry K. Vaughn teamed up with landscape architect Ralph D. Cornell to create a general plan for the new campus, to be partially funded by the WPA and the PWA. The first building was the Commerce Building, next was the Administration and Social Sciences building, then the Technical Trades building.

Fullerton College 300 building–a WPA building and the first built on campus. Photo by the author. Fullerton Museum Center (301 N Pomona Ave): Fullerton’s first public library was an Andrew Carnegie-funded library built in 1907. Years of wear (and the 1933 earthquake) necessitated a re-building. In 1941, the Carnegie Library was demolished, and a new library was re-built by WPA workers. The building was dedicated in 1942. A new library (on Commonwealth) was built in 1973, and the Fullerton Museum Center has occupied the building since 1974.

Fullerton Museum Center building. Photo by the author. Post Office (202 E Commonwealth Ave): The first federally-owned building in Fullerton, it was built in 1939 and funded by the Department of the Treasury, and built by crews of local workers. This post office also contains the mural “Orange Pickers” by Paul Julian, funded by the Treasury Department Section of Fine Arts. Paul Julian went on to have a very successful career at the Warner Bros. studios animating Looney Tunes shorts.

Post Office mural. Photo by the author. Police Station/Former City Hall (237 W Commonwealth Ave): The impressive Spanish Colonial Revival building is now home to Fullerton’s police department. Designed by architect George Stanley Wilson, the building was completed in 1942. One of the most distinctive features of the building is its extensive tile work.

City Hall under construction. Photo courtesy of Fullerton Public Library Local History Room.

Fullerton Police Station (former City Hall) today. Photo by the author. “The History of California” Mural in the Police Station: A three-part mural for which the WPA’s Federal Art Project commissioned artist Helen Lundeberg to paint in 1941. The mural depicts everything from the landing of Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo in San Diego in 1542 to the birth of the aircraft and movie industries in Los Angeles in roughly chronological order. Here are some photos I recently took of the mural. Unfortunately, you have to make an appointment with the police department to see this public work of art:

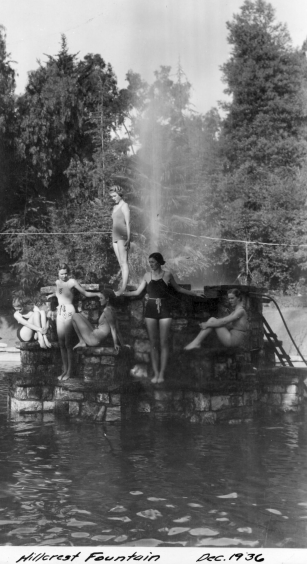

Hillcrest Park (1200 N Harbor Blvd): The amount of work done in Hillcrest Park during the New Deal was staggering, with projects being funded and constructed by the CWA, WPA, RFC, and SERA. Much of Hillcrest Park’s landscaping was done during this era, like the excavation of the “Big Bowl.” Perhaps the most iconic feature of Hillcrest Park is the Depression-era stonework that runs throughout the Park. Today, Hillcrest Park represents the finest example of a WPA-era park in Orange County and has enjoyed federal recognition since 2004, so the structures are safe.

Hillcrest Park Fountain. Photo courtesy of Fullerton Public Library Local History Room.

Hillcrest Park stonework. Photo by the author. Amerige Park (300 W Commonwealth Ave): A wooden grandstand and stone pilasters were built at the baseball field in 1934. The grandstand was destroyed by a fire in the 1980s, but the flagstone pilasters remain.

Amerige Park baseball game in the 1930s. Photo courtesy of Fullerton Public Library Local History Room. Pastoral California: The Story of a Mural

“Pastoral California,” the 75-foot long fresco mural on the side of the Auditorium at Fullerton Union High School was painted in 1934, during the Great Depression, painted over by order of the Board of Trustees in 1939, and restored 58 years later in 1997. The story of this mural, what it depicts, why it was painted over, and finally restored, is one worth reflecting upon.

In addition to building projects, the WPA also commissioned murals in cities across America, including Fullerton, in an effort to give people not just jobs, but a sense of hope and beauty in difficult times. Perhaps the most famous of these murals is “Pastoral California,” one of the two largest frescoes commissioned by the WPA.

Charles Kassler, who had studied art at Princeton, traveled extensively, and apprenticed under a fresco painter in France, completed “Pastoral California” in 1934. Kassler had only one hand. He’d lost the other in a high school chemistry accident. He was married to famous Mexican singer Luisa Espinel, who was the aunt of pop superstar Linda Ronstadt.

Kassler clearly did local history research before painting the mural. It depicts a Spanish/Mexican southern California. From the 1700s to 1821, California was controlled by Spain. From 1821 to 1848, it was controlled by Mexico. Around that time, the United States decided it was their “Manifest Destiny” to control California, so they took it through a war of conquest, the Mexican American War. Kassler, however, chose to depict not an Anglo-American California, but a Spanish/Mexican one.

“Pastoral California” mural. Photo by the author. The mural depicts historical figures like Jose Antonio Yorba, a large landowner whom Yorba Linda is named after. In the background is Mission San Juan Capistrano. To the right is Pio Pico, the last Mexican governor of California. Most of the figures are Latinos doing everyday activities: washing clothes, riding horses, eating together.

Detail from “Pastoral California” mural depicting Pio Pico, the last governor of Mexican California and famous Californio singer Laura Moya. 1930s LA art critic Merle Armitage praised the mural: “Kassler has adhered not only to the beautiful traditions of pastoral California, but at the same time has also borne in mind the splendid Spanish architecture, and, lastly, created a beautiful fresco of amazing vitality and freshness of viewpoint.”

Dr. H. Lynn Sheller taught English and History at Fullerton College in 1934, at the time “Pastoral California” was painted. “I watched him [Charles Kassler] put the mural up there,” Sheller recalled in an interview for the Fullerton College Oral History Program, “I would visit him day after day as he was working…the feature of a fresco is that the paint is mixed in with the plaster, thus it is supposed to be permanent.”

But not everyone was happy with Kassler’s mural.

An article from August 30, 1939 in the Fullerton News-Tribune entitled “High School Mural Doomed; Paint it Out, Trustees Order” reads:

“Fullerton Union high school’s much discussed and criticized mural which covers the outside west wall of the auditorium received its death sentence at the hands of district trustees last night who ordered the wall paint sprayed to cover the painting.

This mural is approximately 75 feet long by 15 feet high with its huge figures of horses and riders and other human forms depicting early California days has been a mooted [sic] point since its completion several [five] years ago by the artist Kassler as a federal art project.

Most occupants of the high school will shed no tears over the decision of the board; it was indicated today as the lurid colors and somewhat grotesque figures have apparently failed to capture popular fancy.”

1939 article from Fullerton News-Tribune courtesy of the Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library. C. Stanley Chapman, son of Fullerton’s first mayor, Charles C. Chapman, and a city council man himself, was one of the ones who “shed no tears.” In an interview for the Cal State Fullerton Oral History Program, Chapman said: “The [mural] down there at the school was almost as absurd [as the one in the post office]. They were painted by that WPA business and the painting did not go with the architecture of the school. It was a great relief when they did paint them out. They were not an artistic addition to the building by any means”

The college student interviewing Chapman replied that superintendent Louis Plummer disagreed with this assessment: “Mr. Plummer seemed to think they were nice although he did not say so. He simply quoted a long article from the Los Angeles Times art critic who said they were lovely and truly representative and that the colors were beautiful. Mr. Plummer ends that little discourse by saying, ‘and they were painted over,’ as though he was disappointed.”

Chapman repied, “Oh, yes, the colors were good. But I have forgotten what the theme was.”

The interviewer reminded him, “Mexican entertainment; with the horses, and the children playing.”

Chapman replied, “Oh, yes, Well, the colors were nice. I don’t know. I was never involved in the school board or anything like that.”

Why was the mural painted over? I have heard some speculate that it was because some of the women depicted in the mural had naked, exposed breasts. However, I have seen no evidence that there was any nudity in the mural. In the mural as it exists today, and in every photo I’ve seen, the women are clothed. Some of them have big breasts, but that hardly seems justification for painting over the whole mural.

The allegedly offending women. “It wasn’t until we had a group of trustees in here who were negatively inclined, that it was painted over,” Sheller remembers. When asked why it was painted over, Sheller said, “Some people felt it was vulgar or gross in some way. It simply showed the Mexican women as they were probably attired at that time. They were very bosomy women. I don’t think that we would feel that there was anything wrong with it. I never felt there was.”

But others have a different view, one I believe makes more sense, given the social context of 1930s Fullerton.

“It was too Mexican, that’s why,” speculated Charles Hart, 75, who was a student at the high school and remembers the mural before it was covered up. “The school board didn’t want to leave the impression that this town was anything else but Anglos. Too extreme for them, I guess.”

Hart said this in a 1997 Los Angeles TImes article.

The decision to paint over this mural probably had to do with its subject matter. It celebrated Mexican culture at a time of heightened racism against Mexicans, and when Mexicans lived in segregated communities, attended segregated schools, and were often forcefully and illegally deported back to Mexico during the Great Depression.

I have written about this at some length in an article entitled “The Roots of Inequality: The Citrus Industry Prospered on the Back of Segregated Immigrant Labor.”

“Pastoral California” remained painted over for six decades years until, in 1997 it was restored, thanks to a massive community effort. I was actually attending Fullerton High School at the time. Some of my friends, art students, helped with the restoration. I remember thinking, even then: Why would anyone have painted over something so beautiful?

A Tale of Two Cities

In the 1920s, Fullerton experienced a housing boom, with numerous new subdivisions being built. With the advent of the Great Depression, much new construction stopped, leading to a housing shortage.

To help with the housing situation, the New Deal established entities like the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which offered affordable home loans and other assistance to homeowners and home buyers.

Fullerton Daily News-Tribune, 1932. In the 1930s, Fullerton was really a “Tale of Two Cities” divided along racial lines. Most neighborhoods had racially restrictive housing covenants that prevented non-whites from renting our purchasing property.

There was really only one relatively small neighborhood–the Truslow/Valencia neighborhood where Latinos and African Americans could purchase homes.

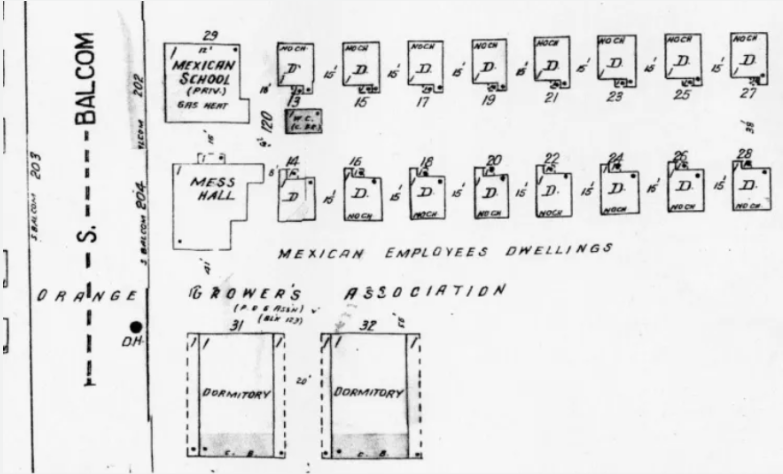

The majority of Latinos living in Fullerton in the 1930s lived in citrus work camps. There was one near downtown at Balcom and Pomona (Campo Pomona), another one near Valencia Ave., and then there were several “colonias” (little communities) on the Bastanchury Ranch (that is, until the mass deportation of 1933).

Campo Pomona. The presence of a large Mexican labor force in the Anglo-dominated towns of Orange County, including Fullerton, led to policies of segregation and second class citizenship for the Mexican workers and their families.

“Mexicans in citrus towns were invariably the pickers and packers; and consequently they were poor, segregated into colonies or villages, and socially ostracized, even though they were economically indispensable to the larger society,” historian Gilbert Gonzalez writes in Labor and Community: Mexican Citrus Worker Villages in a Southern California County, 1900-1950. “The class structure in rural areas has generally divided along lines of nationality. At the top, the growers, native-born white; at the bottom, the foreign-born migrants, or his or her children.”

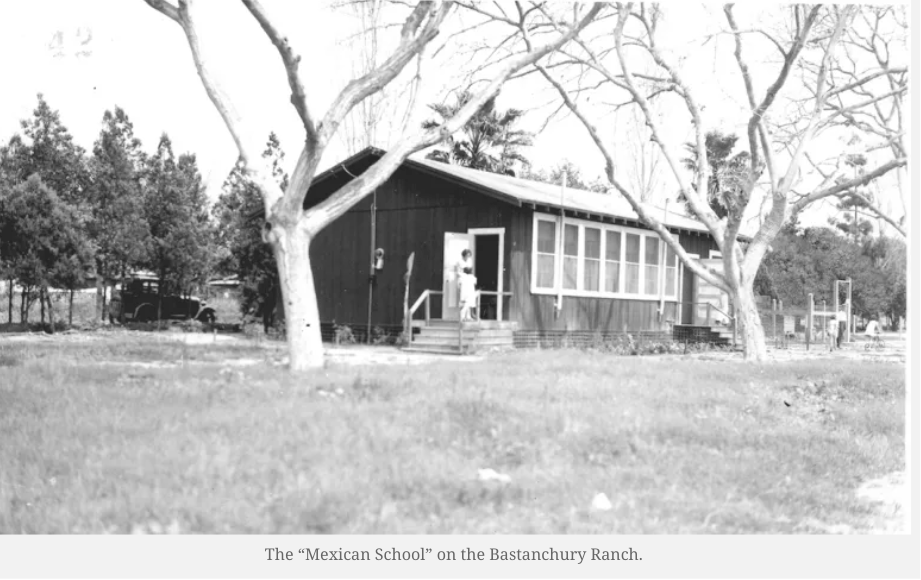

Segregation and structural inequality also extended to education. In the camps, there were schools built exclusively for the Mexican children.

“Segregated schooling assumed a pedagogical norm that was to endure into the fifties and parallels in remarkable ways the segregation of African Americans across the United States,” Gonzalez writes. “By the mid-1920s, the segregated schooling process in the county expanded, matured, and solidified, was manifested in fifteen exclusively Mexican schools [throughout Orange County], together enrolling nearly four thousand pupils. All the Mexican schools except one were located in citrus growing areas of the county…Distinctions between Mexican and Anglo schools included differences in their physical quality.”

There were at least two “Mexican Schools” in Fullerton–one on the Bastanchury Ranch and another in Campo Pomona.

Fullerton Grammar School at Wilshire and Lawrence, which no longer exists. Notice the difference in quality with the Mexican School. Unlike at the white schools, curriculum at the Mexican schools were generally limited to vocational subjects, and junior high was considered the end of schooling for most students, many of whom accompanied their parents in the groves and packinghouses.

One woman who taught at these segregated “Mexican Schools” was Arletta Kelly. In an interview for the CSUF Oral History Program, Kelly described her struggle to convince her colleagues that Mexican students had the same potential as whites.

“Some of my colleagues here would laugh at me and say, ‘Are you a wetback?’” she said.

In addition to educating children, teachers at the “Mexican schools” also taught “Americanization” classes to adults—to assimilate the workers to American society.

“Whereas the Americanization programs in the local villages appear unique, in reality they reflected a generalized expression for the eradication of national cultural differentiation across the United States,” Gonzalez writes.

Under the California Home Teachers Act of 1915, Americanization programs focused on the teaching of English.

Louis E. Plummer, superintendent of the Fullerton High School District, staunchly supported Americanization because in his view the persistence of “Little Italys, Little Chinas, Little Mexicos” stifled the development of a “homogeneous people.” In particular, the failure of Mexicans to live in a “model way” or as “first class citizens,” which was produced by “a hangover of lazy independence” made it imperative that rather than merely learning skills, Mexicans had to learn and live within the fundamental cultural norms of the United States. His perspective summarized much of the Americanization spirit in the larger community during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“Many a surviving villager resident has not forgotten that in their youth the ‘Anglos never wanted to have anything to do with us except that we pick their oranges.’ Such was the nature of the dominant contours in the Mexican and Anglo social relations in the citrus towns,” Gonzalez writes.

Mass Deportation of Mexican Immigrants

With unemployment on the rise during the Great Depression, immigrants (as always) made a convenient scapegoat and there were calls to restrict immigration.

The Great Depression proved disastrous for the Bastanchury family, owners of “the largest orange grove in the world.” Unable to pay their debts, the Bastanchury Ranch went into receivership, and lost most of their property.

According to Druzilla Mackey, a teacher in the Mexican camp schools, “The American Community…felt that the jobs done so patiently by Mexicans for so many years should now be given to them. ‘Those’ Mexicans instead of ‘our’ Mexicans should ‘all be shipped right back to Mexico where they belong’…And so, one morning we saw nine train-loads of our dear friends roll away back to the windowless, dirt-floor homes we had taught them to despise.”

Fullerton Daily News-Tribune, 1933. What she is referring to is a mass deportation of nearly all of the Mexican workers on the Bastanchury Ranch in the early 1930s. This deportation was part of a much larger deportation effort across the United States, which is described at length in the book Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s.

“Outside of the community, the Mexican became the scapegoat,” Gonzalez writes. “In 1931 and 1932, local and county governments caught up in the drive across the Untied States to deport Mexicans sought to cut budgets through repatriating Mexicans. Induced through threats of relief cutoff sweetened with an offer of free transportation, about 2,000 left Orange County.”

Many of those deported were actually American citizens. A few years ago, I had the privilege of interviewing Fullerton resident Manuel Rivas Maturino, who was born on the Bastanchury Ranch, and remembers the experience of “repatriation.”

“All of the Mexican camps on the ranch have been eliminated and all American labor is being used with 28 houses on the ranch now filled with regular employees, nearly all of whom have been continuously on the payroll since last April,” the News-Tribune reported in 1933. “Nine carloads of Mexicans, including 437 adults and children–mostly children–were deported from Orange county today to points on the Mexican border, where they were to re-enter their native country.”

Despite these mass deportations, local growers realized that they needed Mexican workers to harvest the orange crop, and so continued to utilize the labor of immigrants.

The 1936 Citrus War