The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library has microfilm from the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune newspaper stretching back to 1893. I am in the process of reading over the microfilm, year by year, to get a sense of what was happening in the town over the years, and creating a mini archive. Here is a compilation of stories from the 1940s.

World War II

After the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States finally entered World War II, which had already been raging for two years. Many young Fullertonians went off to war.

“Many tears rolled down the cheeks of proud mothers and fathers who saw their sons and other relatives off to induction stations,” the News-Tribune reported in 1942. “Fullerton citizens quickly adjusted themselves to the war…every phase of Civilian Defense was organized quickly here…Red Cross activities boomed…War bonds sales went over with a smashing success, the quota being topped every month in Fullerton…Tire rationing, food stamp, auto use stamp and other new regulations brought on by the war were met without confusion here…’Let’s Knock Out the Axis’ seemed to be the the theme of the city’s efforts throughout the year.”

Prior to World War II, the United States didn’t have nearly the big military it does today, so people had to pitch in by buying war bonds and participating in salvage drives to beef up the war machine.

Everyone had a job, from air raid wardens, to a home guard, to a civilian defense council, to auxiliary police, and more.

“Deep in the sub-basement of the city hall, surrounded by heavy reinforced concrete, in what is generally conceded the most adequate bomb-proof shelter in Fullerton, the control center of the civilian defense council meets each week,” the News-Tribune reported.

Just as World War II was the catalyst for greatly increasing the size of the U.S. military, the war also prompted a huge increase in war-related industries like aerospace, shipbuilding, and weapons manufacture. Many of these new defense industries were located in California.

“Northern Orange county, including Fullerton, has approximately 1.400 men and women engaged in war industries, principally aircraft and shipbuilding,” the News-Tribune reported. “Of the little army of 1,400 workers who are commuting to their war industry jobs, more than 750 are from the city of Fullerton.”

Val Vita Food Products (later called Hunt Foods) in Fullerton had a contract to supply the military with canned goods.

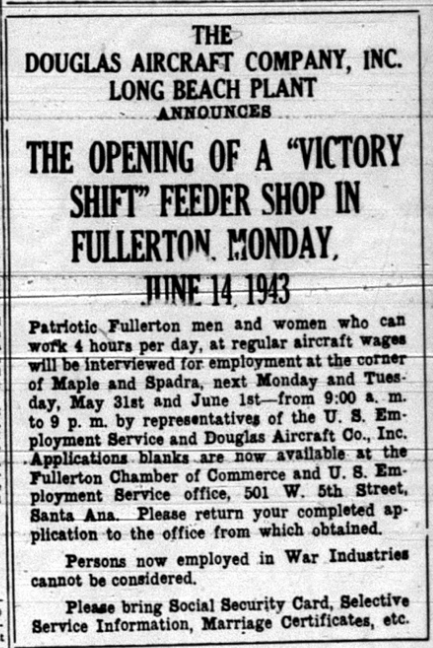

Douglas Aircraft opened a “feeder” shop in Fullerton for local workers to assemble airplane and other parts.

Local industries, like Kohlenberger Engineering and Hunt Foods produced products for the war. Kohlenberger built transimission systems for Amphibious Landing Craft, like the kind used in the invasion of Normandy on D-day.

Another way to contribute to the war effort was by growing your own food in a “Victory Garden,” so more foodstuffs could be sent overseas.

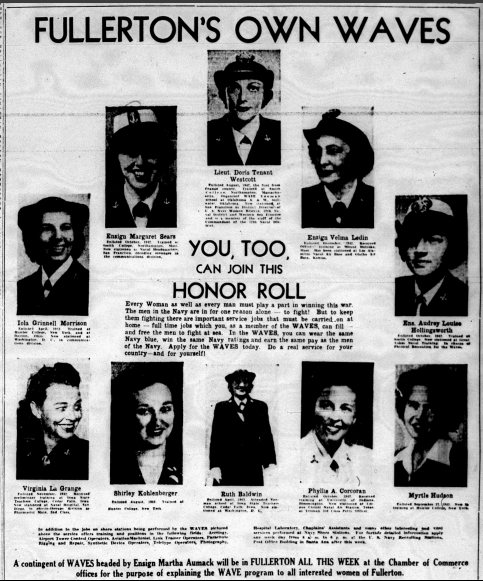

World War II opened up many new opportunities for women, who were recruited to work in local war industries, and to serve in WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) as a women’s branch of the Naval Reserve.

The following article from 1943 gives a good sense of the changing ideas about gender roles that World War II brought about.

“The thing that surprises everyone is that Fullerton residents who never before have done any such kind of work are building intricate wiring assemblies for Flying Fortresses and C-47 transport planes. And they are doing the work well!

Naturally, the average housewife looks puzzled when, for the first time in her life, she faces the problem of using a soldering iron.

“Why I’ll never be able to learn how to use that thing,” she usually says.

There’s an answer that has yet to fail. The plant instructor smiles at the perplexed pupil and replies:

“If our boys from Fullerton can learn to fire machine guns and jump in parachutes, surely we can learn to run this little old soldering iron.”

And within a week or so, the new pupil has taken a place on the production line, doing vitally needed work which boosts America’s war efforts.

During World War II, Nazi war prisoners were taken to camps (including one in Garden Grove) and “hired” out to lower growers.

Japanese Incarceration

In 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, ordering all “enemy aliens” to be removed from their homes and ultimately sent to incarceration/concentration camps for the duration of the war.

Over 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry, many of whom were American citizens, were detained and removed without due process, merely because they looked like the “enemy.” It was one of the most shameful episodes in modern American history.

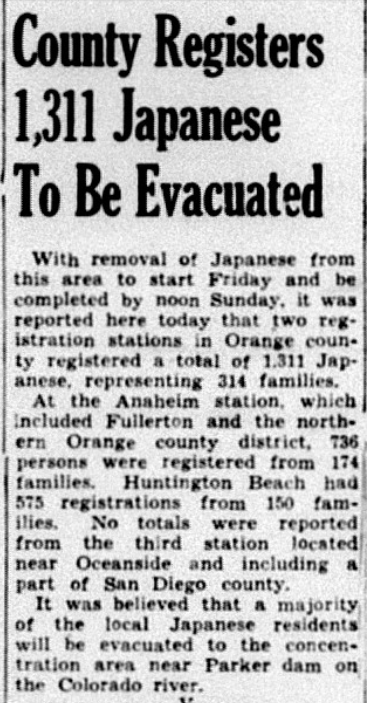

“Three civilian exclusion orders which will evacuate Japanese and enemy aliens from Orange county and a small section of northern San Diego county were issued late Saturday by Lieut Gen. J.L. DeWitt,” the News-Tribune reported. “This order will mean that all Japanese still remaining in Fullerton and Orange county areas will be evacuated by next Sunday noon.”

This local order affected about 700 people, including some living in Fullerton. Formal placards containing the notices were posted throughout the area by soldiers. Ultimately, over 1,300 Japanese Americans were taken away from their homes in Orange County.

While direct blame for this injustice is usually placed at the feet of President Roosevelt, it’s important to note that Japanese exclusion/incarceration was a very popular idea and was merely the outward manifestation of long-standing racism against Japanese-Americans. Quotes from the News-Tribune in 1942 show that state and local leaders across the political spectrum supported Japanese incarceration:

“The League of California Cities asked President Roosevelt to order immediate evacuation of all Japanese, American-born as well as alien from the western combat zone.”

“Federal, state and county authorities in Los Angeles began an investigation which may result in seizure of Japanese-owned property.”

“California congressmen and other public officials have advocated removal of all aliens from the state, instead of merely moving them back from the defense zone.”

“The Orange County grand jury recommended to the board of supervisors today that all Japanese, German, and Italian aliens and their children be removed from Orange County.”

“For weeks the West Coast, through city councils and city officials, patriotic organizations and civic groups, has been demanding all Japanese be removed from the coast as a safeguard against fifth column sabotage and invasion threats.”

Sometimes people were given warning, other times they were just rounded up without notice.

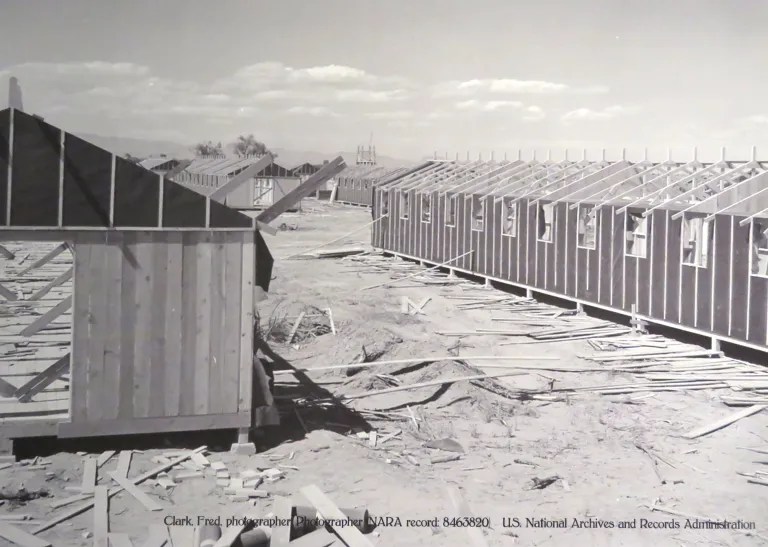

The closest Japanese incarceration camp in California was Manzanar, built in the Owens Valley, but this was not the only one. Prior to being sent to these camps, some local Japanese Americans were sent to the Santa Anita race track and other temporary facilities, which were converted into a temporary relocation center.

One such Japanese American was Betty Oba Masukawa, who was born and raised in Fullerton. In an interview for the CSUF Oral History Program, she recalls her experiences during WWII. I am amazed at the matter-of-fact way she recalls her experiences, and the fact that, years later, she is able to laugh about it:

CSUF: You mentioned evacuation. What was your major concern at the beginning of the war?

Betty: Honestly, I didn’t think anything of it, because I was born here. I didn’t pay any attention to any of the rumors, until it was really happening.

CSUF: How were you told about the evacuation?

Betty: It was in the newspaper.

CSUF: And what were your feelings at the time that you found out about the evacuation?

Betty: If we had to evacuate, we had to evacuate (laughter).

CSUF: What sorts of provisions did you make?

Betty: You mean our home?

CSUF: Yes.

Betty: The mayor of Fullerton, William Hale and his son Harold took care of all our things. We gave him power of attorney and he took care of our ranch; we had a ranch at that time. Well, it was my parents’ ranch. He took care of all our personal belongings for us, so we had no worry.

CSUF: Was he a friend of your family?

Betty: Yes, a very good friend. The whole family was very good. My personal things he took to his house, and he stored it up in his room, which he didn’t have to; he could have just put it in the garage. But, no, he put it in his house, and really took very good care.

CSUF: Where were you then sent?

Betty: We were sent to Poston, Arizona.

CSUF: From Fullerton?

Betty: From the Anaheim train station. We were the last family to go from Orange County.

CSUF: And you went on the train?

Betty: Yes.

CSUF: And what was it like when you arrived in Arizona?

Betty: Terrible.

Betty’s husband (Mas): It was hot and dusty. Rattlesnakes all over.

Betty: If it wasn’t rattlesnakes, it was scorpions.

CSUF: What was the physical building that you lived in at Poston like?

Betty: Like barracks, a lot of cracks in it, you know, so the dust could go through.

CSUF: Oh dear. What time of year was that?

Betty: In May. A really hot time. It was really hot.

CSUF: You were in a barracks with how many people?

Betty: Well, each barrack had four rooms; it was all partitioned. We had the font, and it was a larger one. The dust blows, and everything gets dusty inside. You can just have tears, you know.

CSUF: So your little girl was how old when you went to Poston?

Betty: Four years old. There was a class in front of our barracks, so she went to school there.

CSUF: Was there a social life going on in camp?

Betty: Yes. There were dances.

Mas: Outdoor baseball.

Betty: Outdoor theater.

CSUF: Do you have any special memories about that period of time?

Betty: Well, a group of friends would come over to our apartment, and we’d play cards and stuff for the evening. That’s about all we could do in the evening.

CSUF: And how long were you in Poston?

Betty: Three and a half years.

Education

In 1940, in a major shake-up, long-time Fullerton High School and Junior College Superintendent Louis Plummer decided to leave the position. Plummer first came to Fullerton Union High School in 1909. He helped organize Fullerton Junior College in 1913, and served as superintendent since 1919. Though no specifics were given, it seems clear that there was tension between Plummer and the Board of Trustees.

“My chief concern through the years of my service here has been, and it must continue to be, the welfare of the school,” Plummer wrote in a letter to the Board. “It is probably that the members of the board will unite harmoniously in support of another, elected to take the duties of this office, than they would in carrying out any program I might propose.”

As further evidence that there was tension between the Board and the administration, fifteen teachers were also released. Plummer’s replacement was F.T. Chemberlen.

In other 1940 news, FUHS’s old auditorium was condemned. With the rise in international tensions, a military training program was begun at the High School.

Superintendent Frederick Chemberlen, who had been hired to replace Louis Plummer, resigned and was replaced by William T. Boyce in 1943, and Stanley Warburton in 1945.

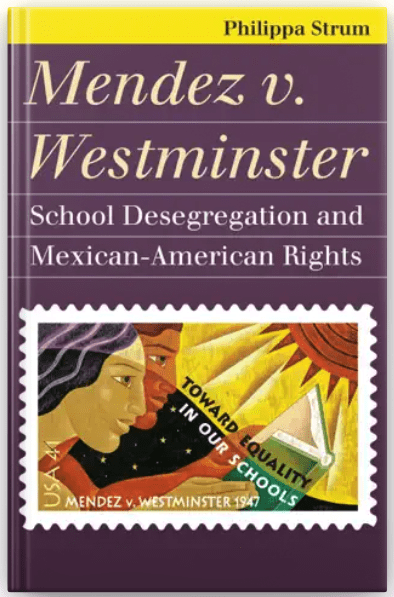

In 1945, segregation of Mexican students from their white peers was being challenged in Orange County in a case that would eventually become Mendez et al v. Westminster.

In the early 20th century, local school districts created separate “Mexican” schools.

“By the mid-1920s there were 15 such schools in Orange County, all but one located in the citrus-growing area that would be involved in Mendez v. Westminster,” Phillipa Strum writes in Mendez v. Westminster: School Desegregation and Mexican American Rights, “by 1931 more than 80 percent of all California school districts with a significant number of Mexican (non-American citizen) and Mexican-American students were segregated, usually through the careful drawing of school zone boundaries by school boards that had been pressured by Anglo residents. The ostensible rationale for the separate schools was the children’s lack of proficiency in English.”

These schools were often of lower quality, both in facilities and materials provided. They “were usually built of wood, while the ‘white’ schools were made out of brick or block masonry…Books and other equipment were castoffs from the ‘white’ schools.”

Many of the “Mexican” schools had shorter hours so that children could join their parents in the fields.

Because of these factors, “Many students had to repeat grades, and they dropped out of school as soon as they could.”

Many Mexican schools, including those in Fullerton, had “Americanization” programs that focused on basic English, math, sanitation, and citizenship. Girls were trained to do housework.

“School boards throughout the state operated on the assumption that segregating what were viewed as the underachieving Mexican-American students was a good thing,” Strum writes. “By 1934, more than 4,000 pupils in Orange County–25 percent of the county’s total student enrollment–were Mexican or Mexican-American. Seventy percent of the county’s students with Spanish surnames were registered in the 15 Orange County elementary schools that had 100 percent Mexican enrollment.”

Unlike elementary schools, high schools in Orange County were, for the most part, integrated. For example, Isabel Martinez graduated from Fullerton High School in 1931, the first Mexican-American to graduate from FUHS.

During World War II between 300,000-500,000 Mexican American men served in the armed forces. This experience of fighting against fascism abroad instilled in many Mexican-Americans a determination to fight for their rights here at home.

One Mexican-American veteran said, “We’d just been at war. We didn’t like it when we came home and found out we’d risked our lives, but now we weren’t treated equally, and that our children wouldn’t be getting as good an education as the white student was going to be getting.”

Gonzalo Mendez was born in Mexico in 1913. He and his family migrated north in the 1920s, settling in Westminster, California. He married his wife Felicitas (an American citizen born in Puerto Rico) in 1935. They opened the Arizona Cafe in a Mexican barrio of Santa Ana.

In 1943, Gonzalo and Felicitas leased a 40-acre asparagus farm from the Munemitsus, a Japanese-American family who had been “relocated” to an internment camp. The Mendez’s traveled to the Arizona internment camp to meet the Munemitsus, who agreed to lease their farm.

There is an excellent children’s book about the friendship between Sylvia Mendez and Aki Munemitsu called Sylvia & Aki.

The Mendezes and their relatives the Vidaurris worked the farm. Meanwhile, Gonzalo became a naturalized citizen.

In 1945, Soleldad Vidaurri went to the Westminster Main School to enroll her two daughters–Alice and Virginia–and her niece and two nephews–Sylvia Mendez, Gonzalo Mendez Jr., and Jerome Mendez–in their neighborhood public school, Westminster Main Elementary School.

“The Vidaurri girls were light-skinned. The Mendez children, however, were visibly darker and, to the teacher, their last name was all too clearly Mexican. They would have to be taken to the “Mexican” [Hoover Elementary] school a few blocks away,” Strum writes.

“We were too dark,” Gonzalo Jr. later recalled.

Carey McWilliams, who wrote a history of Mexican Americans, described the Anglo Westminster school as “handsomely equipped” with “green lawns and shrubs” whereas the “Mexican” Hoover School had “meager equipment [that] matches the inelegance of its surroundings.”

Gonzalo, the father of Sylvia, Gonzalo Jr, and Jerome did not want his children to go to the “Mexican” school, especially because Westminster Main was closer to their house.

“Gonzalo went to the Westminster school the day after his children were turned away and spoke to the principal, but his children were still not permitted to register. The following day he went to the Westminster School Board, where he was equally unsuccessful. Eventually he went to the Orange County school board, again to no avail,” Strum writes.

Henry Rivera, who worked for the Mendezes, told Gonzalo about lawyer David C. Marcus, who had worked for the Mexican consulates in Los Angeles and San Diego.

Marcus, the son of immigrants himself, had experienced anti-Semitism in his life. He was married to Maria Yrma Davila, a Mexican immigrant.

The Mendezes joined with other families in Garden Grove, Santa Ana, and El Modena and brought a class action suit against the four school districts, their superintendents, and all the members of the school boards on behalf of “some 5,000 persons of Mexican and Latin descent,” all of them citizens and residents of the four districts.

The petitioners were Mendez and his children Sylvia, Gonzalo Jr, and Jerome; William Guzman and his son Billy; Frank Palomino and his children Arthur and Sally; Thomas Estrada and his children Clara, Roberto, Francisco, Sylvia, Daniel, and Evalina; and Lorenzo Ramirez and his sons Ignacio, Silverio, and Jose.

Marcus argued that the segregation of Mexican students deprived them of their federal right to equal treatment by the state, as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. He also argued that Orange County was violating California law which at the time allowed segregation only of Asian and Indian children. Mexicans were considered “white.”

Marcus used the wording “Mexican or Latin descent or extraction” rather than “race.”

In 1945, segregation on the basis of race was officially legal–this was before Brown v. Board of Education.

The case was assigned to Judge Paul J. McCormick.

The lawyers for the school districts argued that the segregation of Mexican-American students was appropriate and for their benefit because the children “were unfamiliar with and unable to speak the English language” when they began school.

Their responses sometimes relied on stereotypes of Mexican-Americans.

The Garden Grove response stated that “a large percentage of said persons [Mexican-Americans] residing in said communities have not been instructed in or are familiar with the proper rules of personal hygiene.”

They also argued that segregation was merely the result of where the students lived, often in segregated neighborhoods.

The thrust of the district’s defense was “that the segregation was based on lack of language proficiency rather than ethnicity.”

Early in the trial, Marcus showed that the Mendez children spoke English.

As the trial began, Judge McCormick stated, “The claim here is that they have just taken the Mexican people, their children, en masse, and drawn a line around where they live and said to them, ‘Now you have to go to a school in this place here. You can’t go to a school here where the others who aren’t of this origin go.’

He quoted from Meyer v. Nebraska: “The protection of the Constitution extends to those who speak other languages as well as to those born with English on the tongue.”

Manuela Ochoa was the first witness on the stand, stating that her children had been denied entry to Lincoln school.

“Marcus wanted to attack segregation itself, and to do so, he first had to demonstrate that the school districts were systematically segregating the students on the basis of ethnicity, without reference to their language or other academic abilities,” Strum writes. “That would knock out the districts’ claim of language facility as the basis for the separation. As Mrs. Ochoa indicated, the children were given no tests before being assigned to ‘Mexican’ schools.”

Garden Grove superintendent James L. Kent, who had written his master’s thesis (called “Segregation of Mexican School Children in Southern California”) argued that all “Mexican” students should be segregated.

“He believed Mexicans constituted a separate and nonwhite race,” Strum writes. “He wrote that Mexicans were ‘an alien race that should be segregated socially’ and this had been accomplished in Southern California ‘by designating certain sections where they might live and restricting these sections to them…Segregation into separate schools seems to be the ideal situation for both parties concerned.’”

Marcus, who had read Kent’s thesis, sought to show the court that Kent’s views, “were based on racism rather than on legitimate pedagogic considerations.”

Kent admitted that there was no special training of the teachers at the “Mexican schools,” and that the teachers there did not speak Spanish. He “admitted that the Garden Grove District intentionally segregated its Mexican American students, regardless of their English proficiency.”

Kent also, stunningly, “admitted that he believed Mexican children were inferior to white children in their educational ability, and that he did not believe Mexican children were white.”

Kent stated that the Mexican child, on average, “is lower intellectually than the child of Anglo-Saxon descent.”

Marcus asked Santa Ana Superintendent of Schools Frank Henderson how the district determined which children were Mexican American.

“By their names,” Henderson replied.

Felicitas Mendez testified: “We always tell our children they are Americans, and I feel I am an American myself, and so is my husband, and we thought that they shouldn’t be segregated like that, they shouldn’t be treated the way they are . So we thought we were doing the right thing and just asking for the right thing to put our children together with the rest of the children there.”

Professor Ralph L. Beals, chair of the Department of Anthropology at the University of UCLA testified that “Segregation defeats the purpose of teaching English, certainly, to the Spanish-speaking child.”

Beals said that segregation also impeded “the assimilation of the child to American customs and ways…a feeling of antagonism is built up in children, when they are segregated in this fashion…The disadvantage of segregation, it would seem to me, would come primarily from the reinforcing of stereotypes of inferiority-superiority, which exists in the population as a whole. The advantages [of desegregation], properly handled, would come, then, in the breaking down of those stereotypes and in the broadening of understanding of people of different cultural background and the understanding of different cultures.”

Judge McCormick asked what would happen if children with varying degrees of facility in English were mixed together. Wouldn’t that be better, in terms of Americanization, than segregation? Yes, Beals replied, “with regard to the Americanization program, the mixed group would become much more rapidly aware of the main trends in American life.”

Marcus’ closing statement was powerful: “Of what avail is our theory of democracy if the principles of equal rights, of equal protection and equal obligations are not practiced…of what avail are the thousands upon thousands of lives of Mexican-Americans who sacrificed their all for their country in this great ‘War of Freedom’ if freedom of education denies the equality of all?”

Judge McCormick handed down his opinion on February 18, 1946, seven months after the trial ended. The verdict was a resounding victory–one that upheld all the plaintiffs’ arguments–segregation violated the state’s own laws.

“The equal protection of the laws pertaining to the public school system in California,” he wrote, “is not provided by furnishing in separate schools the same technical facilities, text books and courses of instruction to children of Mexican ancestry that are available to the other public school children regardless of their ancestry.”

Their actions, he concluded, reflected “a clear purpose to arbitrarily discriminate against the pupils of Mexican ancestry and to deny them the equal protection of the laws.”

He wrote that Mexican-Americans as a group were protected by the Fourteenth Amendment and could not legitimately be discriminated against.

The four school districts appealed the decision.

Strum writes that the Mendez decision “had a marked impact on local Mexican-American organizing efforts.” In Ontario, Mexican-American protests led the town to desegregate its Grove School. Similar protests took place in Riverside.

“In Pomona, a group of 50 young Mexican-Americans, most off them WWII veterans, created a Unity League to help organize against discrimination and to push the candidacies of Mexican-americans running for office,” Strum writes.

The case also caused a strong reaction in the legal community.

The NAACP, the American Jewish Congress (AJC), the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), and the national office of the ACLU all supported the case at the appeals level with amicus briefs.

Robert Carter of the NAACP later said of his amicus brief, “I used it as a trial run for Brown.”

Robert W. Kenney, attorney general of California, submitted an amicus brief in support of the Mendez decision.

The Appeals court upheld McCormick’s decision that the school districts had violated California law. The districts would have to desegregate or carry their appeal to the US Supreme Court.

The school districts did not appeal the Ninth Circuit’s decision to the US Supreme Court.

“Because the case had been decided on the basis of California law rather than the Fourteenth Amendment, the case carried legal weight only in California,” Strum writes. “It had a substantial impact nonetheless.”

In 1947 the California state legislature passed a bill ending segregation based on race, repealing laws permitting the segregation of Indian and Asian children.

The Orange County school districts more or less complied with the ruling.

“Anglo parents in El Modena, however, continued to resist desegregation. Many transferred their children to other districts; later, they managed to have part of the district itself transferred to the nearby, all-white Tustin district,” Strum writes.

“The case got the Mendez children and other Mexican-American children in California the education that enabled so many of them to become lawyers, judges, doctors, nurses, teachers, and legislators,” Strum writes. “For them, Mendez made the American dream reality.”

When the war ended, the Munemitsu family returned to Westminster, and got their farm back from the Mendez family, as agreed.

The three Mendez children went to school at Westminster Man, which now housed all the district’s children in grades one through four.

“Sylvia went on to college and became a registered pediatric nurse. Jerome joined the armed forces and served as a Green Beret for many years; Gonzalo Jr became a master carpenter,” Strum writes.

Sylvia Mendez dedicated herself to educating the public about the case.

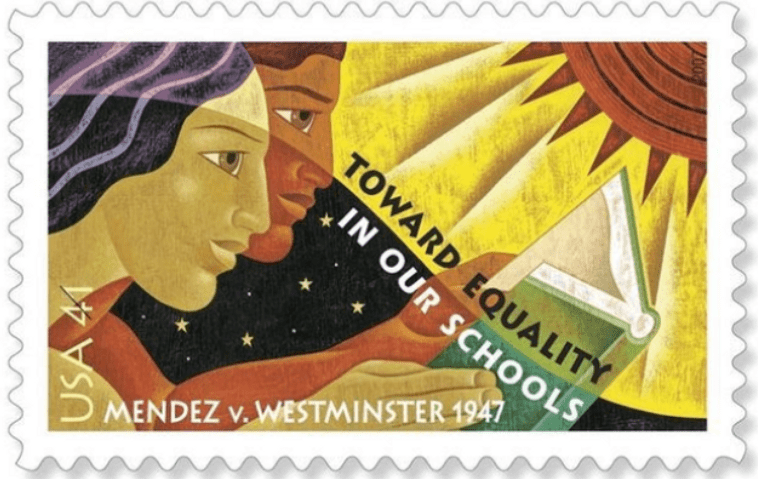

In 2007, the US Postal Service issued a stamp entitled “Mendez v. Westminster 1947: Toward Equality in Our Schools.”

Strum acknowledges that the struggle for school desegregation has not always been linear, noting the persistent fact of de facto segregation due to historic housing patterns: “As of the first decade of the 21st century, the majority of Mexican-Americans–like far too many African American students–were in [de facto] segregated urban schools.”

Gary Orfield and Chungmei Lee of UCLA’s Civil Rights Project reported that in 2006-2007, “Latino students across the country attended schools in which more than half the students were Latino. Ninety percent of Latino students in California were in such schools; 50 percent of them went to schools where Latinos made up 90 percent of the student body.”

In 2008 the California legislature passed a bill mandating the teaching of Mendez as part of the state’s social studies curriculum. Governor Schwartzenegger vetoed it.

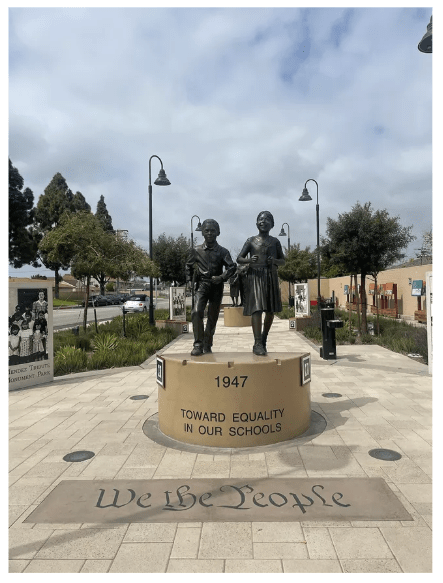

There is a park and trail in Westminster dedicated to Mendez v. Westminster.

To accommodate the population growth, new schools were constructed. In 1949, Fullerton opened Valencia Park school. New schools and expansion of existing schools were often paid for with bonds.

Housing and Civil Rights

While large swaths of former orange groves were being removed to make way for buildings, the citrus industry was still a notable presence in Fullerton, and would remain so through the 1960s.

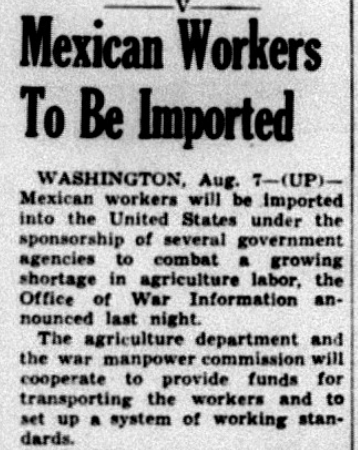

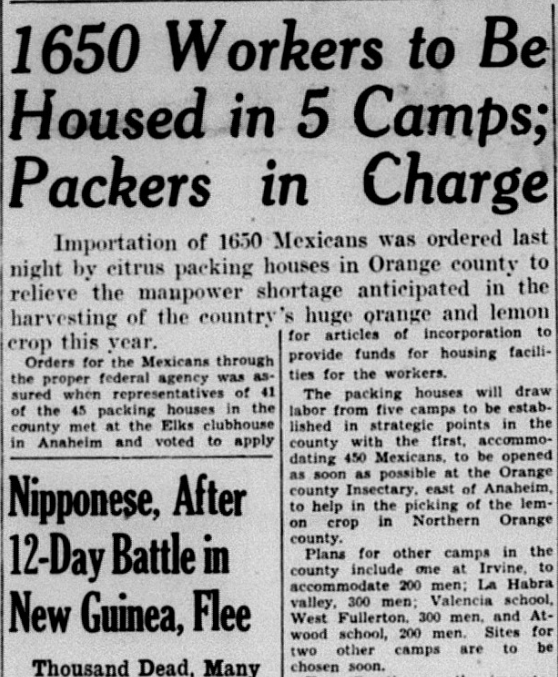

The war created a shortage of farm labor. This led to the establishment of the Bracero Program in 1942, in which thousands of Mexican men were recruited to work in agriculture and other vital industries. Local high school students were also enlisted to work in local agriculture.

Most of the Mexican men who came to pick oranges and other crops in Orange County lived in segregated camps that were built for them. One of the camps was located near downtown Fullerton, at Balcom and Commonwealth avenues. This became known as Campo Pomona.

“The Mexican nationals are in America as essential war workers and deserve to be treated as such. They may be recognized by the white badges they wear, with large black numbers below the letters “C.G.” These men are here to work and are inclined to cause no trouble,” the News-Tribune reported in 1943. “It is to the men’s advantage to live in the camps which have been provided for them. In fact, the county health department rightly insists upon this.”

An article in the News-Tribune expressed local concerns about the new arrivals: “Will the Mexican nationals remain in Orange county permanently? No! They are here by special contract and will return to Mexico at the expiration of that contract.”

The following 1943 article gives a good summation of the Bracero Program in Orange County:

Mexico’s contribution to the war effort in Orange County is now in full sway with the arrival of over 2,000 Mexican national “war workers” to aid in the harvesting of the county’s huge citrus crop.

This information was learned at a luncheon held at the new Mexican camp on S. Balcom St., in Fullerton yesterday when city and county officials and representatives of service clubs and growers gathered as guests of the Placentia Orange Growers Association to obtain facts regarding the new Mexican labor and for a tour of the camps in northern Orange county.

Realizing that the draft and the defense plants had taken a large portion of the available labor formerly employed in the harvesting of over 35,000 carloads of fruit in the county, the industry looked to the Mexican government for help. Under a contract entered into between the Citrus Growers Inc, representing 99 percent of the industry of the county, and federal agency handling the importation of Mexican nationals arrangements were completed early this-year to bring the 2,000 Mexican workers into the county.

Housed in seven camps in strategic sections of the county, these Mexicans are assigned to various packinghouses for the picking of the fruit. The largest of the camps, which were visited bv the group yesterday, are the Imperial camp, located south of La Habra, where 450 are housed and the camp south of Anaheim where 435 are being cared for.

The other camps in the northern section of the county are the Fullerton camp, accommodating 100 men and the Atwood school (in Placentia) where 25 are being housed.

The large presence of of Mexicans in Fullerton was sometimes protested by white residents. During the Bracero Program, some citrus growers sought to supplement their workforce with undocumented immigrants.

A 1946 census showed that, while Fullerton’s population was 12,173, there were only 96 Black people living in the city. Orange County has historically had a very low Black population due to housing (and other forms of) discrimination.

In a 1946 student essay, African-American student Robert Goodwin (son of famous Fullerton author Ruby Berkeley Goodwin), described the specific type of housing discrimination Black people faced in Fullerton at this time:

“Many people in Fullerton do not know that there are only certain sections where Negroes and Mexicans can live. This is due to the fact that years ago when Fullerton was first being settled, real estate men found out that they got lower prices for the property where Mexicans lived; so they enacted a law called the Restrictive Covenant. This forced the Negroes and Mexicans into one small section. This condition has caused many deaths in Fullerton because it forces large and small families to live in houses that are run down, badly roofed, and badly lighted. Such conditions are play grounds for Tuburculosis and other diseases.

“At present we have two drives on. One is to feed the starving children of the world and the other is to clothe and house them. We are taught that “Charity begins at home.” Such should be the case in Fullerton. “Restrictive Covenants” have been in effect too long. It’s time the people of Fullerton stopped talking about equality and started practicing it. When I was small I used to wonder about our “Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag.” When I’d get to the part, “With Liberty and Justice for All,” I knew that part of the pledge didn’t apply to me.

“Let us of Fullerton strive to do better. Let’s make the future Mexican an Negro children of Fullerton know that the “Pledge of Allegiance to our Flag,” isn’t just a bunch of fancy words: but that it is their guarantee of equal rights in the country that their fathers along with their white brothers fought for.”

Many Mexican Americans at this time did not live in regular neighborhoods, but rather in segregated citrus camps, or colonias, and white people did not not want these anywhere near their neighborhoods.

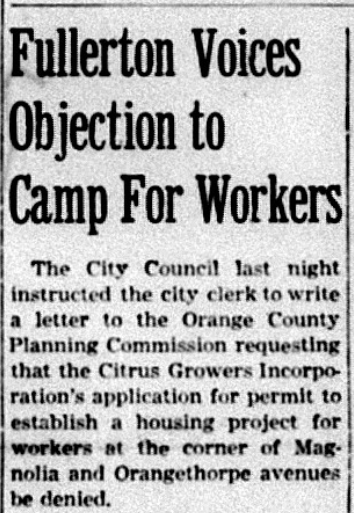

In 1946, when a new colonia was planned for the west side of town (at Orangethorpe and Magnolia), local white residents successfully blocked its construction.

“A group of property owners appeared before the council and presented a petition signed by 148 property owners and renters in that neighborhood voicing their objections,” the News-Tribune reported. “Objections raised were that since the neighborhood was fully developed as a residential district, the establishment of the camp would diminish the value of the residential area; that the quality of the usual people in such camps was not satisfactory and would create unwelcome problems.”

George A. Graham, manager of Citrus Growers, Inc., the company attempting to build the camp, argued that it “was the only site large enough and that there may be need for 3000 workers for next season who needed a place to live.”

After hearing the residents’ objections, Fullerton City Council, and then the Orange County Planning Commission, denied approval of the proposed camp.

Today, when Americans think about the term “segregation” they are probably thinking about the South–where segregation was loudly and publicly enforced until it became officially illegal (though unofficially still practiced) through various court cases and Civil Rights legislation.

Many Americans are probably not as aware that housing and school segregation actually extended far beyond the south and affected every part of the United States. In the North and out West, segregation was kept quieter, but it was pervasive.

By the 1920s, the most common method for enforcing residential segregation was something called “racially restrictive covenants.” These were agreements on the deeds of housing that prevented non-whites from renting or purchasing those homes. These covenants were standard practice among developers and realtors all over the US including in Fullerton.

Because of these covenants, for the first half of the 20th century, most neighborhoods in Fullerton were off-limits to people who weren’t white. Mexican-Americans, by far the largest minority group, were confined to agricultural work camps or carefully proscribed “barrios.”

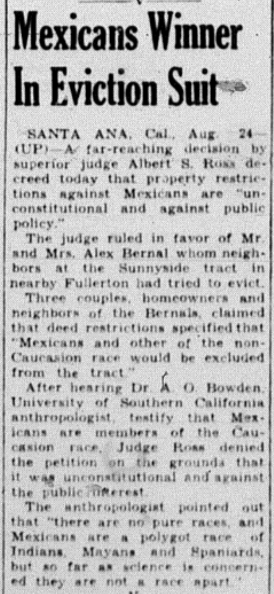

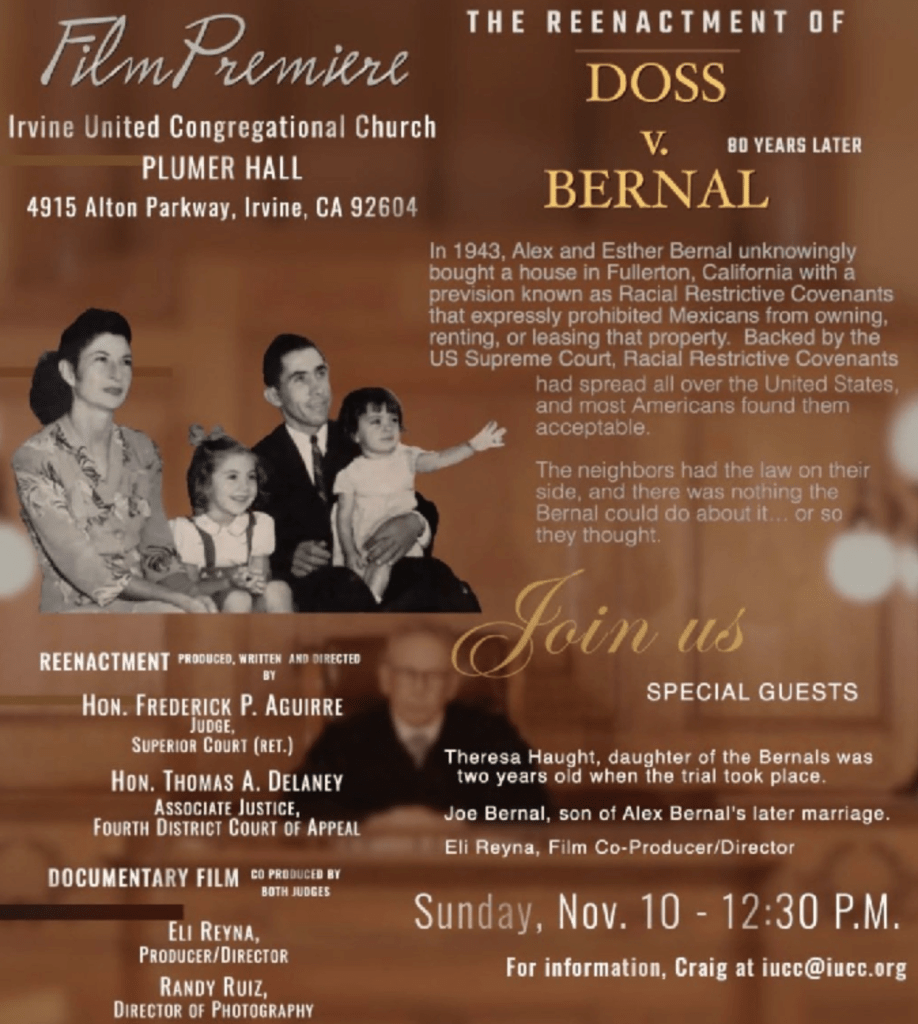

However, in 1943, a Mexican American family in Fullerton–Alex and Esther Bernal–challenged this widespread practice, and won. The legal case was called Doss v. Bernal.

“Doss v. Bernal successfully challenged the residential segregation of Mexican Americans in Orange County, resulting in one of the earliest legal victories against racial housing covenants in the United States,” Robert Chao Romero and Luis Fernandez write in “Doss v. Bernal: Ending Mexican Apartheid in Orange County.”

This case preceded by five years the more well-known (at least among civil rights lawyers) Shelly v. Kraemer (1948), a Supreme Court case which declared racially restrictive covenants legally unenforceable.

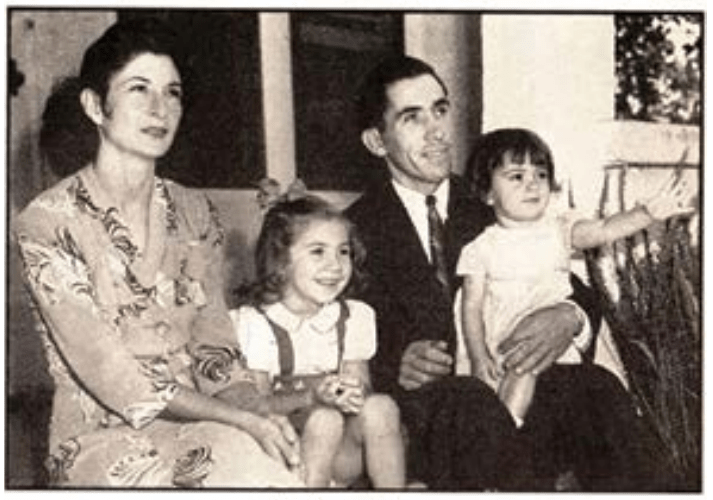

Born in Corona, Alex Bernal was raised in Fullerton’s Truslow barrio. He married Esther Munoz De Anda in 1937 and the couple had two children, Irene and Maria Teresa. Alex worked as a produce truck driver. To accommodate their growing family, the Bernals decided to purchase a white stucco home at 200 E. Ash in a neighborhood called the Sunnyside Addition, near but outside the Truslow barrio.

Unbeknownst to the Bernals, this house, like all the others in the Sunnyside Addition, had a racially restrictive covenant which stated “That no portion of the said property shall at any time be used, leased, owned or occupied by any Mexicans or persons other than of the Caucasian race.”

Despite this restriction, the owners Joe and Velda Johnson sold the property to the Bernals, and the family moved into their new home–happily following their American dream.

“For many Mexican Americans, suburban homeownership symbolized a chance towards upward mobility,” Shannon Anderson writes in Remembering the Bernals: Untangling the Relationship Between Race, Space, and Public Memory in Fullerton, California. “Additionally, suburbanization allowed Mexican Americans to stake their claim to permanent American identity in defiance of the stereotype that all people of Mexican descent were migratory, temporary residents.”

But their white neighbors were not so happy.

“Within a week of living on East Ash Avenue, the Bernals returned home one evening to find that someone had broken into their new home and thrown all their possessions into the street,” Anderson writes. “In a separate incident, Esther answered the door to a man who described himself as an officer of the law. In a ‘vulgar manner,’ he told Esther that she and Alex should move out of their new house because the white residents didn’t want Mexicans living in their neighborhood.”

When this harassment failed to get the Bernals to move, all the neighbors signed a petition saying they wanted the Bernals out. When that didn’t work, some of their neighbors (the Dosses, Shrunks, and Hobsons) filed a lawsuit in the OC Superior Court “on behalf of a majority of all the other lot owners” of the Sunnyside Addition requesting legal enforcement of the racially restrictive housing covenant.

The neighbor’s legal complaint is a clear expression of the racist social attitudes of the time:

“The permitting of Mexicans and other races to live in and to use and occupy the residence buildings in said tract, would necessitate coming in contact with said other races, including Mexicans in a social and neighborhood manner, and that if said race and Mexican Residential use and restriction in said tract of land is broken, other Mexicans and persons of other races will soon move in and occupy residences in said Restricted residential district, and that the value of said residential property therein will be greatly depreciated…and for further reasons that such breach of said restrictions and conditions will greatly lower the social living standard.”

After being served this legal complaint, the Bernals still refused to leave. Instead, they hired lawyer David Marcus to defend their rights. Marcus, a Jewish lawyer who was married to a Mexican woman, would go on to represent Orange County Mexican American families fighting school segregation in the landmark 1947 case Mendez et al v. Westminster.

The first judge assigned to the Bernal’s case, Justice Morrison of Orange County, tried to issue a ruling against the Bernals before the case even went to trial. Marcus successfully petitioned to have an outside judge, Albert F. Ross, brought all the way down from Shasta County in northern California to hear the case.

The Doss v. Bernal trial took place in late August, 1943 in the Old Orange County courthouse in Santa Ana.

One of the central points of contention in the trial was whether the Bernals, and by extension all Mexican Americans, were “white.” Race is, of course, a social construct, not a biologically meaningful concept. It was meaningful insofar as it could be weaponized to exclude people like the Bernals. The plaintiffs’ lawyer Gus Hagenstein tried to prove that Mexican Americans were a part of a distinct race (not white), and Marcus argued that the Bernals should be classified as white. Both sides brought in anthropologists to try to sort this out.

One anthropologist explained that there were three types of races: European, Negroid, and Mongoloid, and that because the Bernals were neither Negroid or Mongoloid, they were more akin to European, and therefore white.

This whole discussion of race ends up sounding pretty silly in retrospect, but it did have repercussions because, according to this “race” argument–covenants that excluded African Americans and Asians could still be considered valid.

Hagenstein also claimed that the presence of Mexican-Americans in suburban neighborhoods would do “irreparable damage” to property values. He brought in real estate professionals, including former Fullerton Mayor Harry Crooke, to attest to this. Marcus sought to refute harmful stereotypes of Mexican Americans in an attempt to show that the Bernals were respectable people who would not be a detriment to their neighbors or bring down property values.

When you really drill down into the logic behind these covenants, they turn out to be based mostly on fear, scientifically dubious ideas about race, and negative stereotypes. What they were mostly about was preserving white supremacy.

The arguments in the Bernal case that would have the most lasting significance had to do with Constitutional rights.

“Marcus cited the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution, which maintain that no one can be ‘deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.’ Unbeknownst to Marcus, this would be the first time that these amendments were successfully invoked in a lawsuit regarding racialized housing discrimination, beginning a trend in subsequent civil rights cases,” Anderson writes.

It was not lost on Marcus that this trial was taking place during World War II, when the United States was fighting against the racist and fascist Nazi Germany in defense of liberty and democracy. Some local Mexican American soldiers even attended the trial in a show of support for the Bernal family.

After a four-day trial, Judge Ross ruled in favor of the Bernals, declaring the racially restrictive covenant “null and void.” He further stated that such covenants were “injurious to the public good and society; violative of the fundamental form and concepts of democratic principles.” He agreed that the covenant violated the 5th and 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

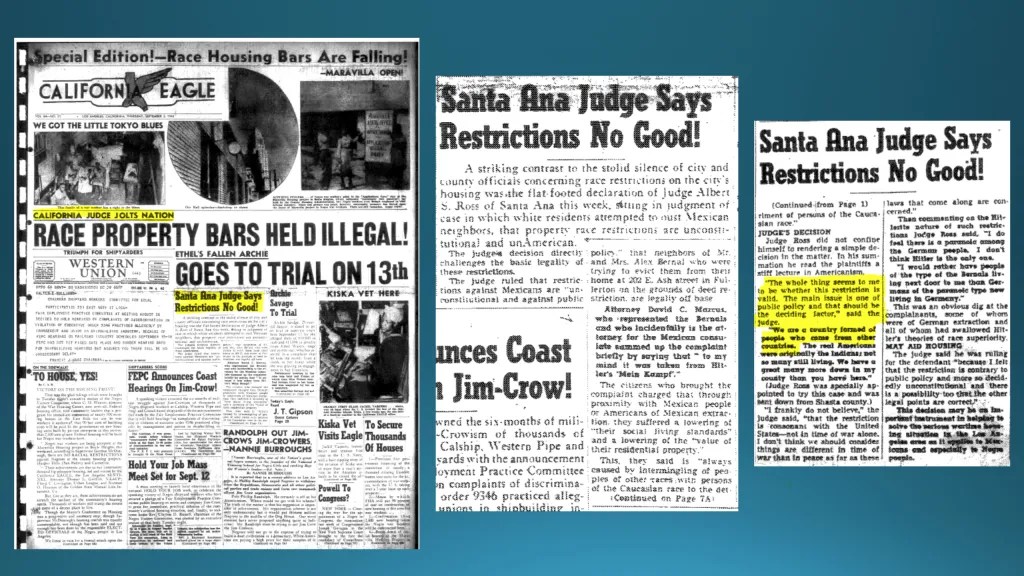

Despite the historic importance of this ruling, it’s interesting that the local press (the Fullerton News-Tribune) barely mentioned the case, devoting just two small articles to it. Neither the Orange County Register nor the Los Angeles Times even mentioned the case.

But other news outlets were paying attention. The Bernals got their picture in Time magazine, along with a story about their legal victory, and were even featured in the radio program “March of Time.”

An African American newspaper in Los Angeles, the California Eagle, featured the Bernal story prominently on the front page with headlines like “Race Property Bars Held Illegal!” and “Santa Ana Judge Says Restrictions No Good!”

Mexican Consul Manuel Aguilar was also paying attention, stating: “We consider any restriction on the rights of Mexicans to live where they please against the Good Neighbor Policy and against the Constitution of the United States.”

Interestingly, “One of the most detailed accounts of the Bernals’ trial comes from the San Antonio, Spanish-language newspaper, La Prensa,” Anderson writes. “Running on multiple pages, ‘Decision en Favor de Una Familia Mexicana Que Reside en Fullerton, California’ details the legal proceedings, including additional statements from Marcus and quotes from Ross’s ruling and subsequent lecture.”

Doss v. Bernal set legal precedent that would eventually lead to the 1948 Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer, which ruled that racially restrictive covenants were legally unenforceable.

But it would be wrong to conclude that Doss v. Bernal ended housing discrimination and segregation in Fullerton or elsewhere.

“Although the outcome of Doss v. Bernal set legal precedent in determining that Mexican Americans are white and racialized housing covenants are unconstitutional, this ruling was not widely enforced in Orange County,” Anderson writes. “Rather, residential space would remain racialized within the region, with instances of racialized housing discrimination against nonwhite individuals cropping up in the decades to come.”

The fact of lingering housing discrimination is perhaps best represented by the fact that in 1964 (21 years after Doss v. Bernal), a majority of California voters passed Proposition 14, which sought to overturn the state’s Rumford Fair Housing Act. This action was later declared unconstitutional, but it sent a strong signal that a majority of white property owners were just fine with housing discrimination.

In a case of history repeating itself, Alex and Esther’s daughter Irene experienced housing discrimination in the 1960s “when she tried to rent an apartment in Fullerton and was refused by the landlord,” Anderson writes. “However, her husband, who was white, had no problem when he applied to rent out the same apartment.”

And although they won, the case was also devastating for the Bernal family.

“Alex and Esther no longer felt safe in their home…the Bernals were concerned that their newfound exposure would result in additional, ramped-up harassment,” Anderson writes. “Thus, the Bernals never got the chance to live in the home that they fought so hard for. Instead, the family of four moved into Alex’s parents’ house. After all that happened, the Bernals ended up back on Truslow Avenue—Fullerton’s segregated barrio designated for residents of color.”

Two years after the trial, Esther Bernal died of cancer at age 29. The stress of the trial likely exacerbated her declining health.

For a while after the trial, the Bernals received dozens of letters of support from all over the United States.

But as time went on, the thing that disappeared in Fullerton was not housing segregation, but public memory of the Doss v. Bernal case.

The case is not mentioned in the two “official” Fullerton history books: Ostrich Eggs for Breakfast by Dora Mae Sim and Fullerton: A Pictorial History by Bob Ziebell.

Even Alex Bernal himself seemed to want to forget, rarely discussing the case, and putting all the letters, clippings, and court files into a box and storing it away for decades.

For nearly 70 years, the Doss v. Bernal case fell out of public memory, sort of like the Pastoral California mural on the side off the high school auditorium, which had been painted over for nearly 60 years.

It was not until 2010 that an intrepid reporter for OC Weekly named Gustavo Arellano and a CSUF grad student named Luis Fernandez re-discovered the story and brought it back into public memory.

In a remarkable piece of local history reporting, Arellano’s “Mi Casa Es Mi Casa: How Fullerton produce-truck driver Alex Bernal helped change the course of American civil rights” re-introduced Orange County to Doss v. Bernal.

For his article, Arellano interviewed Bernal family members, pored through Alex’s box of old letters and files, and unearthed old news stories about the case.

Fernandez would go on to co-author an excellent 2012 article for UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center, entitled “Doss v. Bernal: Ending Mexican Apartheid in Orange County.”

The story of Doss v. Bernal was featured in a 2022 book entitled A People’s Guide to Orange County by Gustavo Arellano, Elaine Lewinnek, and Thuy Vo Dang.

In 2023, CSUF graduate student Shannon Anderson wrote a Master’s thesis entitled Remembering the Bernals: Untangling the Relationship Between Race, Space, and Public Memory in Fullerton, California. Her study highlights omissions in previous narratives, like the role of Esther Bernal in purchasing the house, and her deposition during the trial.

That same year, the Orange County Hispanic Bar Association (OCHBA) hosted a live reenactment of the Doss v. Bernal trial.

Anderson describes how in some cases, popular retellings have oversimplified the Bernal story into one of total victory, of having ended housing discrimination and segregation.

A 2023 article in the Fullerton Observer, reporting on the reenactment of the trial, was titled “A Reenactment of the 1943 Historical Trial that ended housing discrimination.”

“The issue with this is that the Bernals’ trial did not immediately put an end to housing discrimination. Although the case set legal precedent that would eventually go on to influence Supreme Court cases, racist housing practices would not be solved, but rather reified over the decades,” Anderson writes. “Also, the Bernal family suffered immensely from their experience with racialized exclusion.”

The problem with seeing the Bernal’s story as one of total victory is that it may prevent us from understanding how housing discrimination still persists.

“Perpetuating the idea that segregation is an issue of the past when it still exists, just in a different form, allows contemporary forms of racialized housing segregation to continue to operate without objection,” Anderson writes. “While racial segregation is no longer enforced on an institutional or legal level, de facto segregation continues to be upheld through longstanding cultural ideas, economic inequality, and social practices.”

A stark expression of this is the racial wealth gap. In 2019, the average income of a Caucasian household in the U.S. was about $188,200, while the average income of a Mexican-American household was $36,100. This gap dictates which neighborhoods Mexican-Americans and people of color can live in.

Rather than seeing Doss v. Bernal as something that ended housing discrimination and segregation, it is more accurate to see the case as part of a decades-long struggle of chipping away at the enduring effects of white supremacy.

There have been two attempts to commemorate the Bernal house as a historically significant property under the Mills Act, in 2010 and 2020, but both attempts were unsuccessful.

“Commemoration of the site would require Fullerton to come to terms with its shameful, racist past,” Anderson writes.

Growth and the Post-War Boom

The 1940 US census found that population growth in Fullerton had slowed significantly during the Great Depression, with a population of about 11,200.

“Discussion of population changes brought out the fact that elementary school registration is nearly 600 below the total of 1930,” the News-Tribune reported. “It also was pointed out that two large Mexican colonies which once flourished on the former Bastanchury ranch, no longer exist and that occupants do not live in Fullerton.”

Fullerton’s two large dams (the Fullerton Dam and the Brea Dam) were completed in 1941, as part of a larger countywide flood control program.

The dams were built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

In 1941, Fullerton (being a member of the Metropolitan Water District) began to receive water from the Colorado River, courtesy of the Colorado River Aqueduct.

The post-war period has been rightly called the “Boom Years.” Fullerton grew quickly. It was a perfect location to build a suburban middle class lifestyle. By 1946, Fullerton’s population was a little over 12,000, with room to grow.

“Large, previously undeveloped areas are being subdivided and plans call for the erection of houses at the rate of city blocks at a time. In addition to lesser buildings programs on W. Wilshire and W. Amerige avenues, Jewett Brothers are preparing a tract on N. Basque ave for construction of 78 homes for sale to war veterans,” the News-Tribune reported in 1946. “In the northern hills of Fullerton is one of the largest subdivisions of its kind in the entire west. Eighteen hundred acres of the Sunny Hills Ranch in this are area available for development of residences. According to planners of this subdivision of rolling hills and orange groves, it will make up one of the most exclusive residential areas in California and will attract new citizens to the extent of doubling the population of the city of Fullerton.”

To accommodate this growth, the city also spent a lot of money expanding the city’s infrastructure, including roads and sewers.

In 1941, Fullerton finally completed construction of City Hall at the corner of Highland and Commonwealth. The building now serves as the police station.

The building was designed by architect by G. Stanley Wilson, and was funded by the WPA, a New Deal federal program.

In addition to housing various city government offices, the building also was home to the Chamber of Commerce, the local welfare department, the police department, and the city jail.

The City Council chambers were also used as a court room for use by the city judge or justice of the peace.

“Most outstanding of city projects to be undertaken is street development, calling for an expenditure of nearly $1,000,000 within the next 10 years,” the News-Tribune stated in 1946. “Under the program being considered the city will build new streets, widen, resurface, and improve existing arterials.”

Fullerton continued to benefit from various New Deal programs, including construction of a new library on the site of the original Carnegie Library (built in 1907). The Library, built in 1940, is now the Fullerton Museum Center. Other public works projects underway in 1940 included flood control measures like construction of the Brea and Fullerton dams and paving of barrancas.

In 1940, the sprawling Sunny Hills Ranch, formerly part of the Bastanchury Ranch, was partly subdivided into residential housing. Unfortunately, the properties had racially restrictive housing covenants.

For those thousands of GIs who were eventually discharged, a new problem emerged—a housing crisis. There was not enough housing for all the vets, and it much of it was too expensive. Both federal and local governments responded by building lots of new housing and establishing programs like the GI Bill that made is affordable for vets to get home loans and go back to college.

Here in Fullerton, homebuilding increased dramatically after the war, and some of the new homes were explicitly for veterans, such as the 25-unit College View adjacent to Fullerton College.

Because housing production and affordability was a national and local priority, both federal and state governments had some form of rent control.

As both Fullerton and Anaheim grew, annexation fights began between the two cities to incorporate land between the two cities. The first salvo of this fight occurred when Anaheim city officials convened a special Saturday session in 1948 to annex a 60-foot strip close to the south border of Fullerton.

In an editorial called “Skulduggery in Anaheim,” the Fullerton News-Tribune reported:

“When a city council finds it necessary to meet in special session on a Saturday, it is either a case of dire emergency or some kind of skulduggery. Anaheim’s city council met in special session last Saturday.

The business before the council consisted of passing a resolution to annex a strip of land 60 feet wide along the south side of Orangethorpe from Highland avenue to a point approximately midway between Harvard [Lemon] and Raymond avenue where a finger of Anaheim’s north city limits extends.

That a city council would hold a special session to pass a resolution to annex a piece of land which seemingly has no immediate bearing o the welfare of Anaheim, such action can hardly be called a “dire emergency.” That leaves only one category under which it can fall: skulduggery!

One need only to study a few of the facts behind the action by the Anaheim council to understand why it went to the trouble of a special Saturday session.

The area along Highway 101 between Fullerton and Anaheim is unincorporated. Its growth and development in recent years have made it obvious that it will some day become a part of some municipality, which would mean either Fullerton or Anaheim. An area of this nature needs the advantages that any city offers: fire and police protection, trash and garbage collection, sewer and water facilities.

Sentiment for becoming part of a municipality has run high in recent years, and especially more since a Metropolitan Water District edict forbids any new users outside the city limits. This ruling checks and futurity development of property in this unincorporated area until it becomes. Part of one city or another.

On September 11 of this year property owners took legal steps for becoming part of Fullerton by filing a notice of intention to circulate a petition relative to annexation of the territory. With enough signatures to the petition the matter could be put to the vote of the people of the area concerned. The people could choose between remaining unincorporated (with a chance of later joining Anaheim) or joining with Fullerton. Property owners who are working to initiate the petition say that the vote would be overwhelmingly for Fullerton.

It is no secret that Anaheim has coveted this territory. It would stand to lose by letting the people express their desires at the ballot box. With the handwriting on the wall, there was only one course for Anaheim to follow: throw up a legal roadblock between the territory and the Fullerton city limits by annexing a piece of land between the two.

It is reminiscent of Hitler’s tactics in instituting his famous “JA” and “neon” ballots during European plebiscites.

Fullerton officials sought to head-off this land-grab by meeting with Anaheim officials, but their efforts came to naught.

It would fall to property owners to sue Anaheim over the annexation move, which they won. But the fight was not over.

The second biggest local news story of 1949 was the annexation fight between Fullerton and Anaheim over a strip of “no man’s land” that once separated the two towns. At stake was future tax dollars from housing and industrial development. After much legal maneuvering, court fights, resident protests, and council meetings, Fullerton won the fight over the coveted land.

The Labor Strikes of 1945-46

Amid all the jubilation and relief following the end of World War II, some of the largest labor strikes in American history swept major industries like cars, oil, motion pictures, coal, steel, canning, and more. Hundreds of thousands of workers struck–with many of them gaining the kind of strong union powers (like collective bargaining for better wages, benefits, and working conditions) that helped build America’s post-war blue collar middle class.

Both the Fullerton News-Tribune and local business elites tended to portray strikers negatively, sometimes associating strikers or unions with communism.

Powerful business interests, like the Associated Farmers and and Employers Industrial Relations Council, who had spent the depression colluding with government to suppress strikes and labor movements, did their part to paint the strikers as dangerous, lawless radicals and communists.

The labor troubles reached Fullerton, with over 400 workers at Hunt Bros. going on strike in 1946. The strikes affected Fullerton in other ways by (briefly) stopping the postal service, travel, and shipping of goods.

“The processing of oranges in Fullerton has been stopped at some plants and greatly retarded in others due to the railroad strike,” the News-Tribune reported in 1946. “The California Fruit Distributors have stopped picking and packing until arrangement can be made to receive oranges in trucks…There is not much danger of losing the crop as the oranges are not too ripe yet.”

The strikes affected peoples’ ability to buy certain foods, like meat. In response, congress passed a “tough” anti-strike bill, the Taft-Hartley Act.

The Cold War

In 1945, the Axis powers surrendered, and the Allies won the War.

Fullertonians decided to honor the war dead with a memorial in Hillcrest Park, listing the 54 names of those Fullertonians who died, inscribed on a huge sequoia tree cross section.

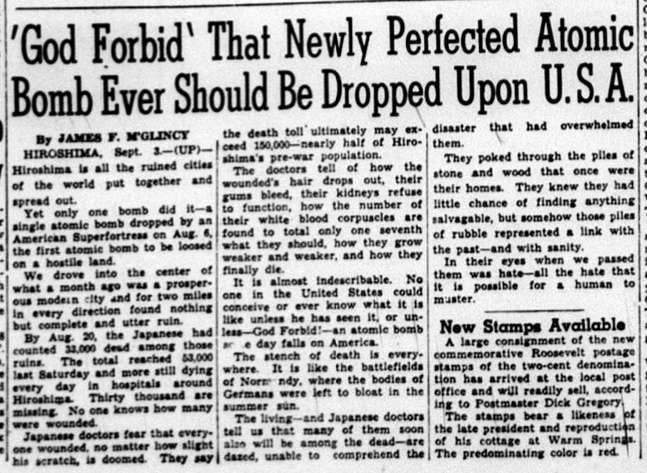

Perhaps the thorniest post-war question was what to do now that the atomic bomb existed–a weapon that could theoretically destroy the world. On a more positive note, congress passed the GI Bill in 1944, which provided veterans with financial aid for housing, education, and more.

The first frosts of the Cold War were being felt between the capitalist west and large communist countries like Russia and (eventually) China, despite the fact that these were our allies during the War. The existence of the atomic bomb, and Russia’s attempts to create one for itself, exacerbated these tensions.

This tension between the US and Russia would also spark increased espionage and paranoia which in the US would eventually become the Red Scare.

Defeated Axis powers Germany and Japan were occupied by Allied powers to ensure they would demilitarize and follow the political path the Allies wanted them to follow.

Both German and Japanese war criminals were tried and executed.

Just as World War I caused the end of old empires like the Ottoman Empire, the end of World War II brought about the beginning of decolonization of European empires like the British and Spanish. India, a former British colony, would achieve independence in 1947.

While European colonial empires were losing some of their power and global reach, the post World War II era saw a rise in the United States’ international military and economic presence around the world. This did not usually take the form of overt colonization (which was becoming out of fashion), but rather took the form of military bases, plus increased US business and political presence globally. Some might call this a new kind of empire.

A young Republican congressman from Yorba Linda named Richard Nixon (who attended Fullerton High School) was making a name for himself by fanning the flames of anti-communism.

“Disclosure of Communist infiltration in high places in the administration in Washington will be made by Congressman Richard M. Nixon, “working” member of the Thomas Committee which unearthed the national intrigue, at a dinner meeting Oct. 13 at 7pm in Santa Ana Masonic Temple,” the News-Tribune reported. “The committee will resume hearings in Washington later and its probe will be largely on the findings Nixon makes. It will mark the first public appearance at which Capt. Nixon has talked in Orange County, although he was guest Oct. 1 of the Chamber of Commerce at Yorba Linda, his home town, where he attended school as a boy. The meeting is to be under the sponsorship of the Orange County Republican Assembly, now headed by Roscoe G. Hewitt of Santa Ana, who recently succeeded Hilmer Lodge of Fullerton as president.”

Local Politics

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected to an unprecedented four terms in office. He died in 1945 during his fourth term, and Harry S. Truman took office. In 1947, Congress approved the 22nd Amendment, which bars presidents from serving more than two terms.

During the 1940 election, Republican candidate Wendell Wilkie made a brief train stop in Fullerton, where he greeted a large crowd.

Those who ran and were elected to City Council throughout the 1940s were all white businessmen who tended to be fairly conservative politically. Here’s a breakdown of who was elected during this period and what line of business they were in:

1940: William Montague, Walter Muckenthaler, and Hans Kohlenberger.

1942: Alfred Beazley, Carl Bowen, Hans Kohlenberger (mayor), William Montague, and Walter Muckenthaler.

1944: Verne Wilkinson, William Montague, and Hans Kohlenberger. Montague, an orange rancher, was selected as Mayor.

1946: Homer Bemis and Irvin C. Chapman (son of Fullerton’s first mayor and powerful citrus grower Charles C. Chapman) were elected to city council in 1946. Bemis was “engaged in real estate, building, brokerage, and development,” according to the News-Tribune. “In the past four years he has been actively engaged in the construction of homes, having built more than 100 homes within this period, with his associates.” Chapman, of course, helped manage the citrus and business empire his father built. Local drug store owner Verne Wilkinson was chosen as mayor.

In 1947, Sam Collins (from Fullerton) was chosen to be Speaker of the California State Assembly. Collins was a very influential politician in Sacramento. He remains the longest-serving Republican Speaker in history.

In 1948, Verne Wilkinson, Hugh Warden, and Thomas Eadington were elected to City Council. Irvin “Ernie” Chapman, son of Fullerton’s first mayor Charles C. Chapman, was chosen as mayor.

Culture and Social Life

In 1940, social clubs were popular in Fullerton, including Rotary, Kiwanis, Lions, Business and Professional Women’s Club, Fullerton Junior Chamber of Commerce, American Legion, 20-30 club, Ebell Club, YMCA, YWCA, Masons, Odd Fellows, and more.

For entertainment, Fullertonians went to see movies at the Fox Theater.

In 1947, a new theater was built—the Wilshire Theater, which has its own interesting history. This eventually was replaced by apartments.

Leo Fender, who had a popular radio repair shop in town, was beginning to design and manufacture electric Fender guitars, although his ads in the local newspaper focused on radios and records.

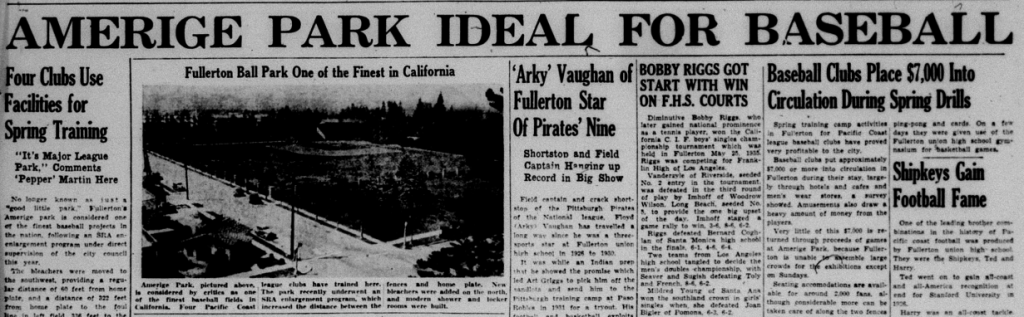

Throughout the 1940s, minor league baseball teams from the Pacific Coast League played games at Amerige Park–like the Portland Beavers, the Los Angeles Angels, the Hollywood Stars, and the Sacramento Solons. Local teams also used the field, including the Fullerton Firemen.

I’m currently reading a newly published book called Spring Training in Fullerton, which is all about this subject. Stay tuned!

Local Pilots Set World Endurance Record

Perhaps the biggest local news event of 1949 was the flight endurance record set by local pilots Dick Reidel and Bill Barris who flew their plane the Sunkist Lady for 1008 hours.