The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

As part of my research into Fullerton history, I like to read books about local and California history to help give broader context for what was happening here. I just finished reading a book called Mendez v. Westminster: School Desegregation and Mexican American Rights by Philippa Strum, which is about a landmark court case in Orange County which held that segregation of Mexican-American children into separate schools was illegal. This case, which was decided in 1947, preceded the more well-known Brown v. Board of Education case by seven years.

Mexican-Americans in California

Mexicans have lived in California for hundreds of years. In fact, prior to the Mexican-American War (1846-48), California (and much of the Southwest) was part of Mexico. Spanish was spoken here before English was.

After California became a U.S. state in 1850, Mexican-Americans continued to live here and to migrate north from Mexico, seeking jobs and opportunity.

“Labor agents recruited workers in Mexico and arranged transportation to the United States for them,” Strum writes. “By the mid-1920s, Mexican workers constituted the bulk of farm laborers throughout the citrus groves of southern California.”

Mexican immigrants and Mexican-Americans often faced housing, educational, and social discrimination and segregation in California, and they were often paid lower wages than their Anglo counterparts.

“Mexican Americans were not chosen for juries. They were not welcome in places of public accommodation such as movie theaters and swimming pools–or, if they were permitted in, they were restricted to the balconies of the movie houses and special “Mexican days” at the pools. Restrictive covenants prevented them from moving into better “white” neighborhoods,” Strum writes. “Many of them settled in poorer neighborhoods–colonias–next to citrus groves or vegetable fields. The Mexican farm laborers who lived on the outskirts of Anglo towns in Orange County in the 1930s found themselves in neighborhoods that for the most part lacked sewers, gas for cooking and heating, paved streets, or sidewalks.”

Nonetheless, Mexican-Americans formed strong and dynamic communities. For more on this, check out my book report on Gilbert Gonzalez’s book Labor and Community: Mexican Citrus Workers Villages in a Southern California County, 1900-1950.

When the Great Depression hit, Mexican-Americans were often scapegoated as taking jobs from white workers, and the Hoover administration began a mass deportation program in 1931.

“An estimated one-third of the entire American Mexican population, comprising more than 500,000 people, left voluntarily or otherwise, even though perhaps 60 percent of them were American citizens. In 1930 at least 2,000 ‘Mexicans’ were repatriated from Orange County alone,” Strum writes.

School Segregation, Southwest-Style

In the early 20th century, local school districts created separate “Mexican” schools.

“By the mid-1920s there were 15 such schools in Orange County, all but one located in the citrus-growing area that would be involved in Mendez v. Westminster,” Strum writes, “by 1931 more than 80 percent of all California school districts with a significant number of Mexican (non-American citizen) and Mexican-American students were segregated, usually through the careful drawing of school zone boundaries by school boards that had been pressured by Anglo residents. The ostensible rationale for the separate schools was the children’s lack of proficiency in English.”

These schools were often of lower quality, both in facilities and materials provided. They “were usually built of wood, while the ‘white’ schools were made out of brick or block masonry…Books and other equipment were castoffs from the ‘white’ schools.”

Many of the “Mexican” schools had shorter hours so that children could join their parents in the fields.

Because of these factors, “Many students had to repeat grades, and they dropped out of school as soon as they could.”

Many Mexican schools, including those in Fullerton, had “Americanization” programs that focused on basic English, math, sanitation, and citizenship. Girls were trained to do housework.

“School boards throughout the state operated on the assumption that segregating what were viewed as the underachieving Mexican-American students was a good thing,” Strum writes. “By 1934, more than 4,000 pupils in Orange County–25 percent of the county’s total student enrollment–were Mexican or Mexican-American. Seventy percent of the county’s students with Spanish surnames were registered in the 15 Orange County elementary schools that had 100 percent Mexican enrollment.”

Unlike elementary schools, high schools in Orange County were, for the most part, integrated. For example, Isabel Martinez graduated from Fullerton High School in 1931, the first Mexican-American to graduate from FUHS.

The Times They are ‘A Changin’

During World War II between 300,000-500,000 Mexican American men served in the armed forces. This experience of fighting against fascism abroad instilled in many Mexican-Americans a determination to fight for their rights here at home.

One Mexican-American veteran said, “We’d just been at war. We didn’t like it when we came home and found out we’d risked our lives, but now we weren’t treated equally, and that our children wouldn’t be getting as good an education as the white student was going to be getting.”

A group of veterans in Santa Ana created the Latin American Organization (LAO), to combat school segregation. The cultural climate was changing.

Gonzalo Mendez was born in Mexico in 1913. He and his family migrated north in the 1920s, settling in Westminster, California. He married his wife Felicitas (an American citizen born in Puerto Rico) in 1935. They opened the Arizona Cafe in a Mexican barrio of Santa Ana.

In 1943, Gonzalo and Felicitas leased a 40-acre asparagus farm from the Munemitsus, a Japanese-American family who had been “relocated” to an internment camp. The Mendez’s traveled to the Arizona internment camp to meet the Munemitsus, who agreed to lease their farm.

There is an excellent children’s book about the friendship between Sylvia Mendez and Aki Munemitsu called Sylvia & Aki.

The Mendezes and their relatives the Vidaurris worked the farm. Meanwhile, Gonzalo became a naturalized citizen.

In 1945, Soleldad Vidaurri went to the Westminster Main School to enroll her two daughters–Alice and Virginia–and her niece and two nephews–Sylvia Mendez, Gonzalo Mendez Jr., and Jerome Mendez–in their neighborhood public school, Westminster Main Elementary School.

“The Vidaurri girls were light-skinned. The Mendez children, however, were visibly darker and, to the teacher, their last name was all too clearly Mexican. They would have to be taken to the “Mexican” [Hoover Elementary] school a few blocks away,” Strum writes.

“We were too dark,” Gonzalo Jr. later recalled.

Carey McWilliams, who wrote a history of Mexican Americans, described the Anglo Westminster school as “handsomely equipped” with “green lawns and shrubs” whereas the “Mexican” Hoover School had “meager equipment [that] matches the inelegance of its surroundings.”

Gonzalo, the father of Sylvia, Gonzalo Jr, and Jerome did not want his children to go to the “Mexican” school, especially because Westminster Main was closer to their house.

“Gonzalo went to the Westminster school the day after his children were turned away and spoke to the principal, but his children were still not permitted to register. The following day he went to the Westminster School Board, where he was equally unsuccessful. Eventually he went to the Orange County school board, again to no avail,” Strum writes.

Henry Rivera, who worked for the Mendezes, told Gonzalo about lawyer David C. Marcus, who had worked for the Mexican consulates in Los Angeles and San Diego.

Marcus, the son of immigrants himself, had experienced anti-Semitism in his life. He was married to Maria Yrma Davila, a Mexican immigrant.

The Mendezes joined with other families in Garden Grove, Santa Ana, and El Modena and brought a class action suit against the four school districts, their superintendents, and all the members of the school boards on behalf of “some 5,000 persons of Mexican and Latin descent,” all of them citizens and residents of the four districts.

The petitioners were Mendez and his children Sylvia, Gonzalo Jr, and Jerome; William Guzman and his son Billy; Frank Palomino and his children Arthur and Sally; Thomas Estrada and his children Clara, Roberto, Francisco, Sylvia, Daniel, and Evalina; and Lorenzo Ramirez and his sons Ignacio, Silverio, and Jose.

Marcus argued that the segregation of Mexican students deprived them of their federal right to equal treatment by the state, as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. He also argued that Orange County was violating California law which at the time allowed segregation only of Asian and Indian children. Mexicans were considered “white.”

Marcus used the wording “Mexican or Latin descent or extraction” rather than “race.”

In 1945, segregation on the basis of race was officially legal–this was before Brown v. Board of Education.

The case was assigned to Judge Paul J. McCormick.

The lawyers for the school districts argued that the segregation of Mexican-American students was appropriate and for their benefit because the children “were unfamiliar with and unable to speak the English language” when they began school.

Their responses sometimes relied on stereotypes of Mexican-Americans.

The Garden Grove response stated that “a large percentage of said persons [Mexican-Americans] residing in said communities have not been instructed in or are familiar with the proper rules of personal hygiene.”

They also argued that segregation was merely the result of where the students lived, often in segregated neighborhoods.

The thrust of the district’s defense was “that the segregation was based on lack of language proficiency rather than ethnicity.”

The Trial Begins

Early in the trial, Marcus showed that the Mendez children spoke English.

As the trial began, Judge McCormick stated, “The claim here is that they have just taken the Mexican people, their children, en masse, and drawn a line around where they live and said to them, ‘Now you have to go to a school in this place here. You can’t go to a school here where the others who aren’t of this origin go.’

He quoted from Meyer v. Nebraska: “The protection of the Constitution extends to those who speak other languages as well as to those born with English on the tongue.”

Manuela Ochoa was the first witness on the stand, stating that her children had been denied entry to Lincoln school.

“Marcus wanted to attack segregation itself, and to do so, he first had to demonstrate that the school districts were systematically segregating the students on the basis of ethnicity, without reference to their language or other academic abilities,” Strum writes. “That would knock out the districts’ claim of language facility as the basis for the separation. As Mrs. Ochoa indicated, the children were given no tests before being assigned to ‘Mexican’ schools.”

Garden Grove superintendent James L. Kent, who had written his master’s thesis (called “Segregation of Mexican School Children in Southern California”) argued that all “Mexican” students should be segregated.

“He believed Mexicans constituted a separate and nonwhite race,” Strum writes. “He wrote that Mexicans were ‘an alien race that should be segregated socially’ and this had been accomplished in Southern California ‘by designating certain sections where they might live and restricting these sections to them…Segregation into separate schools seems to be the ideal situation for both parties concerned.’”

Marcus, who had read Kent’s thesis, sought to show the court that Kent’s views, “were based on racism rather than on legitimate pedagogic considerations.”

Kent admitted that there was no special training of the teachers at the “Mexican schools,” and that the teachers there did not speak Spanish. He “admitted that the Garden Grove District intentionally segregated its Mexican American students, regardless of their English proficiency.”

Kent also, stunningly, “admitted that he believed Mexican children were inferior to white children in their educational ability, and that he did not believe Mexican children were white.”

Kent stated that the Mexican child, on average, “is lower intellectually than the child of Anglo-Saxon descent.”

Marcus asked Santa Ana Superintendent of Schools Frank Henderson how the district determined which children were Mexican American.

“By their names,” Henderson replied.

Felicitas Mendez testified: “We always tell our children they are Americans, and I feel I am an American myself, and so is my husband, and we thought that they shouldn’t be segregated like that, they shouldn’t be treated the way they are . So we thought we were doing the right thing and just asking for the right thing to put our children together with the rest of the children there.”

Professor Ralph L. Beals, chair of the Department of Anthropology at the University of UCLA testified that “Segregation defeats the purpose of teaching English, certainly, to the Spanish-speaking child.”

Beals said that segregation also impeded “the assimilation of the child to American customs and ways…a feeling of antagonism is built up in children, when they are segregated in this fashion…The disadvantage of segregation, it would seem to me, would come primarily from the reinforcing of stereotypes of inferiority-superiority, which exists in the population as a whole. The advantages [of desegregation], properly handled, would come, then, in the breaking down of those stereotypes and in the broadening of understanding of people of different cultural background and the understanding of different cultures.”

Judge McCormick asked what would happen if children with varying degrees of facility in English were mixed together. Wouldn’t that be better, in terms of Americanization, than segregation? Yes, Beals replied, “with regard to the Americanization program, the mixed group would become much more rapidly aware of the main trends in American life.”

Marcus’ closing statement was powerful: “Of what avail is our theory of democracy if the principles of equal rights, of equal protection and equal obligations are not practiced…of what avail are the thousands upon thousands of lives of Mexican-Americans who sacrificed their all for their country in this great ‘War of Freedom’ if freedom of education denies the equality of all?”

Judge McCormick handed down his opinion on February 18, 1946, seven months after the trial ended. The verdict was a resounding victory–one that upheld all the plaintiffs’ arguments–segregation violated the state’s own laws.

“The equal protection of the laws pertaining to the public school system in California,” he wrote, “is not provided by furnishing in separate schools the same technical facilities, text books and courses of instruction to children of Mexican ancestry that are available to the other public school children regardless of their ancestry.”

Their actions, he concluded, reflected “a clear purpose to arbitrarily discriminate against the pupils of Mexican ancestry and to deny them the equal protection of the laws.”

He wrote that Mexican-Americans as a group were protected by the Fourteenth Amendment and could not legitimately be discriminated against.

From the Court of Appeals to the State Legislature

The four school districts appealed the decision.

Strum writes that the Mendez decision “had a marked impact on local Mexican-American organizing efforts.” In Ontario, Mexican-American protests led the town to desegregate its Grove School. Similar protests took place in Riverside.

“In Pomona, a group of 50 young Mexican-Americans, most off them WWII veterans, created a Unity League to help organize against discrimination and to push the candidacies of Mexican-americans running for office,” Strum writes.

The case also caused a strong reaction in the legal community.

The NAACP, the American Jewish Congress (AJC), the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), and the national office of the ACLU all supported the case at the appeals level with amicus briefs.

Robert Carter of the NAACP later said of his amicus brief, “I used it as a trial run for Brown.”

Robert W. Kenney, attorney general of California, submitted an amicus brief in support of the Mendez decision.

The Appeals court upheld McCormick’s decision that the school districts had violated California law. The districts would have to desegregate or carry their appeal to the US Supreme Court.

The school districts did not appeal the Ninth Circuit’s decision to the US Supreme Court.

“Because the case had been decided on the basis of California law rather than the Fourteenth Amendment, the case carried legal weight only in California,” Strum writes. “It had a substantial impact nonetheless.”

In 1947 the California state legislature passed a bill ending segregation based on race, repealing laws permitting the segregation of Indian and Asian children.

The Orange County school districts more or less complied with the ruling.

“Anglo parents in El Modena, however, continued to resist desegregation. Many transferred their children to other districts; later, they managed to have part of the district itself transferred to the nearby, all-white Tustin district,” Strum writes.

Conclusion

“The case got the Mendez children and other Mexican-American children in California the education that enabled so many of them to become lawyers, judges, doctors, nurses, teachers, and legislators,” Strum writes. “For them, Mendez made the American dream reality.”

When the war ended, the Munemitsu family returned to Westminster, and got their farm back from the Mendez family, as agreed.

The three Mendez children went to school at Westminster Man, which now housed all the district’s children in grades one through four.

“Sylvia went on to college and became a registered pediatric nurse. Jerome joined the armed forces and served as a Green Beret for many years; Gonzalo Jr became a master carpenter,” Strum writes.

Sylvia Mendez dedicated herself to educating the public about the case.

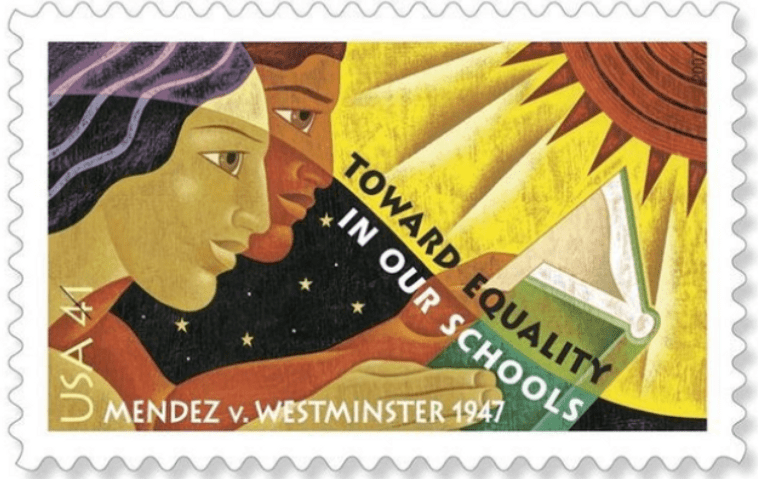

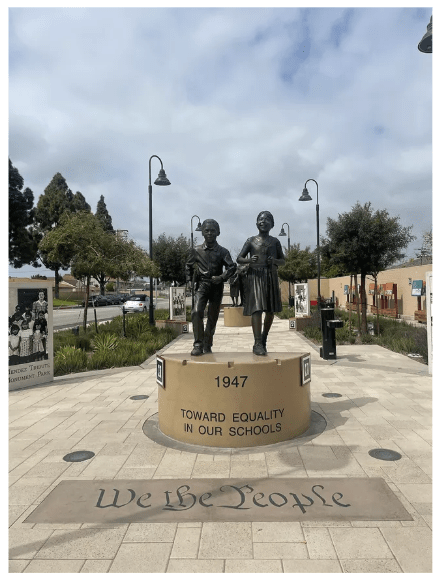

In 2007, the US Postal Service issued a stamp entitled “Mendez v. Westminster 1947: Toward Equality in Our Schools.”

Strum acknowledges that the struggle for school desegregation has not always been linear, noting the persistent fact of de facto segregation due to historic housing patterns: “As of the first decade of the 21st century, the majority of Mexican-Americans–like far too many African American students–were in [de facto] segregated urban schools.”

Gary Orfield and Chungmei Lee of UCLA’s Civil Rights Project reported that in 2006-2007, “Latino students across the country attended schools in which more than half the students were Latino. Ninety percent of Latino students in California were in such schools; 50 percent of them went to schools where Latinos made up 90 percent of the student body.”

In 2008 the California legislature passed a bill mandating the teaching of Mendez as part of the state’s social studies curriculum. Governor Schwartzenegger vetoed it.

There is a park and trail in Westminster dedicated to Mendez v. Westminster.

“The tale of what these people accomplished begins on land owned by Japanese-Americans and leased by Mexican-Americans. As it unfolds, the nation’s largest African-American civil rights organization becomes involved, and so do associations of Jewish-Americans and Japanese-Americans. It is not a melting pot story, but more like a kaleidoscope,” Strum writes.