The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Today, when Americans think about the term “segregation” they are probably thinking about the South–where segregation was loudly and publicly enforced until it became officially illegal (though unofficially still practiced) through various court cases and Civil Rights legislation.

Many Americans are probably not as aware that housing and school segregation actually extended far beyond the south and affected every part of the United States. In the North and out West, segregation was kept quieter, but it was pervasive.

By the 1920s, the most common method for enforcing residential segregation was something called “racially restrictive covenants.” These were agreements on the deeds of housing that prevented non-whites from renting or purchasing those homes. These covenants were standard practice among developers and realtors all over the US including in Fullerton, California–the subject of my research.

Because of these covenants, for the first half of the 20th century, most neighborhoods in Fullerton were off-limits to people who weren’t white. Mexican-Americans, by far the largest minority group, were confined to agricultural work camps or carefully proscribed “barrios.”

However, in 1943, a Mexican American family in Fullerton–Alex and Esther Bernal–challenged this widespread practice, and won. The legal case was called Doss v. Bernal.

“Doss v. Bernal successfully challenged the residential segregation of Mexican Americans in Orange County, resulting in one of the earliest legal victories against racial housing covenants in the United States,” Robert Chao Romero and Luis Fernandez write in “Doss v. Bernal: Ending Mexican Apartheid in Orange County.”

This case preceded by five years the more well-known (at least among civil rights lawyers) Shelly v. Kraemer (1948), a Supreme Court case which declared racially restrictive covenants legally unenforceable.

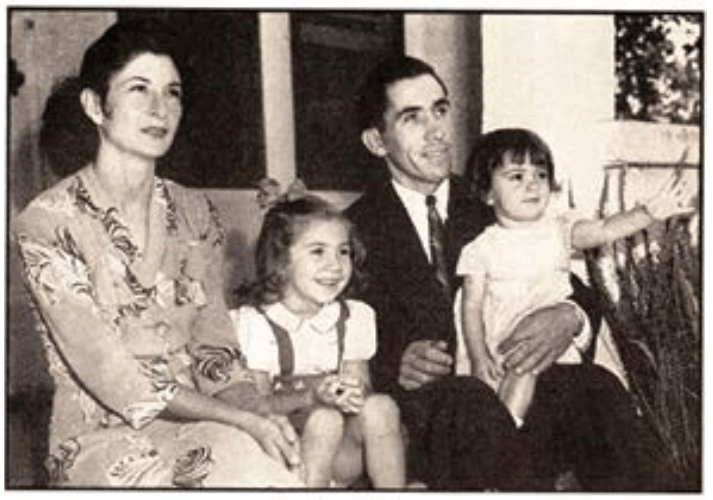

Born in Corona, Alex Bernal was raised in Fullerton’s Truslow barrio. He married Esther Munoz De Anda in 1937 and the couple had two children, Irene and Maria Teresa. Alex worked as a produce truck driver. To accommodate their growing family, the Bernals decided to purchase a white stucco home at 200 E. Ash in a neighborhood called the Sunnyside Addition, near but outside the Truslow barrio.

Unbeknownst to the Bernals, this house, like all the others in the Sunnyside Addition, had a racially restrictive covenant which stated “That no portion of the said property shall at any time be used, leased, owned or occupied by any Mexicans or persons other than of the Caucasian race.”

Despite this restriction, the owners Joe and Velda Johnson sold the property to the Bernals, and the family moved into their new home–happily following their American dream.

“For many Mexican Americans, suburban homeownership symbolized a chance towards upward mobility,” Shannon Anderson writes in Remembering the Bernals: Untangling the Relationship Between Race, Space, and Public Memory in Fullerton, California. “Additionally, suburbanization allowed Mexican Americans to stake their claim to permanent American identity in defiance of the stereotype that all people of Mexican descent were migratory, temporary residents.”

But their white neighbors were not so happy.

“Within a week of living on East Ash Avenue, the Bernals returned home one evening to find that someone had broken into their new home and thrown all their possessions into the street,” Anderson writes. “In a separate incident, Esther answered the door to a man who described himself as an officer of the law. In a ‘vulgar manner,’ he told Esther that she and Alex should move out of their new house because the white residents didn’t want Mexicans living in their neighborhood.”

When this harassment failed to get the Bernals to move, all the neighbors signed a petition saying they wanted the Bernals out. When that didn’t work, some of their neighbors (the Dosses, Shrunks, and Hobsons) filed a lawsuit in the OC Superior Court “on behalf of a majority of all the other lot owners” of the Sunnyside Addition requesting legal enforcement of the racially restrictive housing covenant.

The neighbor’s legal complaint is a clear expression of the racist social attitudes of the time:

“The permitting of Mexicans and other races to live in and to use and occupy the residence buildings in said tract, would necessitate coming in contact with said other races, including Mexicans in a social and neighborhood manner, and that if said race and Mexican Residential use and restriction in said tract of land is broken, other Mexicans and persons of other races will soon move in and occupy residences in said Restricted residential district, and that the value of said residential property therein will be greatly depreciated…and for further reasons that such breach of said restrictions and conditions will greatly lower the social living standard.”

After being served this legal complaint, the Bernals still refused to leave. Instead, they hired lawyer David Marcus to defend their rights. Marcus, a Jewish lawyer who was married to a Mexican woman, would go on to represent Orange County Mexican American families fighting school segregation in the landmark 1947 case Mendez et al v. Westminster.

The first judge assigned to the Bernal’s case, Justice Morrison of Orange County, tried to issue a ruling against the Bernals before the case even went to trial. Marcus successfully petitioned to have an outside judge, Albert F. Ross, brought all the way down from Shasta County in northern California to hear the case.

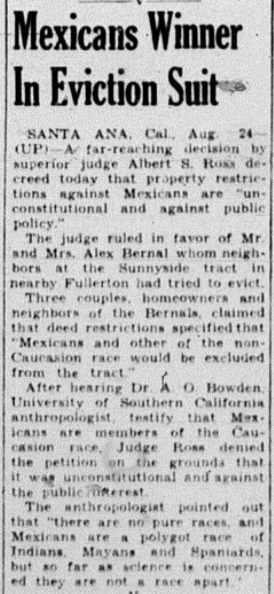

The Doss v. Bernal trial took place in late August, 1943 in the Old Orange County courthouse in Santa Ana.

One of the central points of contention in the trial was whether the Bernals, and by extension all Mexican Americans, were “white.” Race is, of course, a social construct, not a biologically meaningful concept. It was meaningful insofar as it could be weaponized to exclude people like the Bernals. The plaintiffs’ lawyer Gus Hagenstein tried to prove that Mexican Americans were a part of a distinct race (not white), and Marcus argued that the Bernals should be classified as white. Both sides brought in anthropologists to try to sort this out.

One anthropologist explained that there were three types of races: European, Negroid, and Mongoloid, and that because the Bernals were neither Negroid or Mongoloid, they were more akin to European, and therefore white.

This whole discussion of race ends up sounding pretty silly in retrospect, but it did have repercussions because, according to this “race” argument–covenants that excluded African Americans and Asians could still be considered valid.

Hagenstein also claimed that the presence of Mexican-Americans in suburban neighborhoods would do “irreparable damage” to property values. He brought in real estate professionals, including former Fullerton Mayor Harry Crooke, to attest to this. Marcus sought to refute harmful stereotypes of Mexican Americans in an attempt to show that the Bernals were respectable people who would not be a detriment to their neighbors or bring down property values.

When you really drill down into the logic behind these covenants, they turn out to be based mostly on fear, scientifically dubious ideas about race, and negative stereotypes. What they were mostly about was preserving white supremacy.

The arguments in the Bernal case that would have the most lasting significance had to do with Constitutional rights.

“Marcus cited the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution, which maintain that no one can be ‘deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.’ Unbeknownst to Marcus, this would be the first time that these amendments were successfully invoked in a lawsuit regarding racialized housing discrimination, beginning a trend in subsequent civil rights cases,” Anderson writes.

It was not lost on Marcus that this trial was taking place during World War II, when the United States was fighting against the racist and fascist Nazi Germany in defense of liberty and democracy. Some local Mexican American soldiers even attended the trial in a show of support for the Bernal family.

After a four-day trial, Judge Ross ruled in favor of the Bernals, declaring the racially restrictive covenant “null and void.” He further stated that such covenants were “injurious to the public good and society; violative of the fundamental form and concepts of democratic principles.” He agreed that the covenant violated the 5th and 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Despite the historic importance of this ruling, it’s interesting that the local press (the Fullerton News-Tribune) barely mentioned the case, devoting just two small articles to it. Neither the Orange County Register nor the Los Angeles Times even mentioned the case.

But other news outlets were paying attention. The Bernals got their picture in Time magazine, along with a story about their legal victory, and were even featured in the radio program “March of Time.”

An African American newspaper in Los Angeles, the California Eagle, featured the Bernal story prominently on the front page with headlines like “Race Property Bars Held Illegal!” and “Santa Ana Judge Says Restrictions No Good!”

Mexican Consul Manuel Aguilar was also paying attention, stating: “We consider any restriction on the rights of Mexicans to live where they please against the Good Neighbor Policy and against the Constitution of the United States.”

Interestingly, “One of the most detailed accounts of the Bernals’ trial comes from the San Antonio, Spanish-language newspaper, La Prensa,” Anderson writes. “Running on multiple pages, ‘Decision en Favor de Una Familia Mexicana Que Reside en Fullerton, California’ details the legal proceedings, including additional statements from Marcus and quotes from Ross’s ruling and subsequent lecture.”

Doss v. Bernal set legal precedent that would eventually lead to the 1948 Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer, which ruled that racially restrictive covenants were legally unenforceable.

But it would be wrong to conclude that Doss v. Bernal ended housing discrimination and segregation in Fullerton or elsewhere.

“Although the outcome of Doss v. Bernal set legal precedent in determining that Mexican Americans are white and racialized housing covenants are unconstitutional, this ruling was not widely enforced in Orange County,” Anderson writes. “Rather, residential space would remain racialized within the region, with instances of racialized housing discrimination against nonwhite individuals cropping up in the decades to come.”

The fact of lingering housing discrimination is perhaps best represented by the fact that in 1964 (21 years after Doss v. Bernal), a majority of California voters passed Proposition 14, which sought to overturn the state’s Rumford Fair Housing Act. This action was later declared unconstitutional, but it sent a strong signal that a majority of white property owners were just fine with housing discrimination.

In a case of history repeating itself, Alex and Esther’s daughter Irene experienced housing discrimination in the 1960s “when she tried to rent an apartment in Fullerton and was refused by the landlord,” Anderson writes. “However, her husband, who was white, had no problem when he applied to rent out the same apartment.”

And although they won, the case was also devastating for the Bernal family.

“Alex and Esther no longer felt safe in their home…the Bernals were concerned that their newfound exposure would result in additional, ramped-up harassment,” Anderson writes. “Thus, the Bernals never got the chance to live in the home that they fought so hard for. Instead, the family of four moved into Alex’s parents’ house. After all that happened, the Bernals ended up back on Truslow Avenue—Fullerton’s segregated barrio designated for residents of color.”

Two years after the trial, Esther Bernal died of cancer at age 29. The stress of the trial likely exacerbated her declining health.

For a while after the trial, the Bernals received dozens of letters of support from all over the United States.

But as time went on, the thing that disappeared in Fullerton was not housing segregation, but public memory of the Doss v. Bernal case.

The case is not mentioned in the two “official” Fullerton history books: Ostrich Eggs for Breakfast by Dora Mae Sim and Fullerton: A Pictorial History by Bob Ziebell.

Even Alex Bernal himself seemed to want to forget, rarely discussing the case, and putting all the letters, clippings, and court files into a box and storing it away for decades.

For nearly 70 years, the Doss v. Bernal case fell out of public memory, sort of like the Pastoral California mural on the side off the high school auditorium, which had been painted over for nearly 60 years.

It was not until 2010 that an intrepid reporter for OC Weekly named Gustavo Arellano and a CSUF grad student named Luis Fernandez re-discovered the story and brought it back into public memory.

In a remarkable piece of local history reporting, Arellano’s “Mi Casa Es Mi Casa: How Fullerton produce-truck driver Alex Bernal helped change the course of American civil rights” re-introduced Orange County to Doss v. Bernal.

For his article, Arellano interviewed Bernal family members, pored through Alex’s box of old letters and files, and unearthed old news stories about the case.

Fernandez would go on to co-author an excellent 2012 article for UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center, entitled “Doss v. Bernal: Ending Mexican Apartheid in Orange County.”

The story of Doss v. Bernal was featured in a 2022 book entitled A People’s Guide to Orange County by Gustavo Arellano, Elaine Lewinnek, and Thuy Vo Dang.

In 2023, CSUF graduate student Shannon Anderson wrote a Master’s thesis entitled Remembering the Bernals: Untangling the Relationship Between Race, Space, and Public Memory in Fullerton, California. Her study highlights omissions in previous narratives, like the role of Esther Bernal in purchasing the house, and her deposition during the trial.

That same year, the Orange County Hispanic Bar Association (OCHBA) hosted a live reenactment of the Doss v. Bernal trial.

Anderson describes how in some cases, popular retellings have oversimplified the Bernal story into one of total victory, of having ended housing discrimination and segregation.

A 2023 article in the Fullerton Observer, reporting on the reenactment of the trial, was titled “A Reenactment of the 1943 Historical Trial that ended housing discrimination.”

“The issue with this is that the Bernals’ trial did not immediately put an end to housing discrimination. Although the case set legal precedent that would eventually go on to influence Supreme Court cases, racist housing practices would not be solved, but rather reified over the decades,” Anderson writes. “Also, the Bernal family suffered immensely from their experience with racialized exclusion.”

The problem with seeing the Bernal’s story as one of total victory is that it may prevent us from understanding how housing discrimination still persists.

“Perpetuating the idea that segregation is an issue of the past when it still exists, just in a different form, allows contemporary forms of racialized housing segregation to continue to operate without objection,” Anderson writes. “While racial segregation is no longer enforced on an institutional or legal level, de facto segregation continues to be upheld through longstanding cultural ideas, economic inequality, and social practices.”

A stark expression of this is the racial wealth gap. In 2019, the average income of a Caucasian household in the U.S. was about $188,200, while the average income of a Mexican American household was $36,100. This gap dictates which neighborhoods Mexican Americans and people of color can live in.

Rather than seeing Doss v. Bernal as something that ended housing discrimination and segregation, it is more accurate to see the case as part of a decades-long struggle of chipping away at the enduring effects of white supremacy.

There have been two attempts to commemorate the Bernal house as a historically significant property under the Mills Act, in 2010 and 2020, but both attempts were unsuccessful.

“Commemoration of the site would require Fullerton to come to terms with its shameful, racist past,” Anderson writes.

Sources:

“Mi Casa Es Mi Casa: How Fullerton produce-truck driver Alex Bernal helped change the course of American civil rights” by Gustavo Arellano, OC Weekly, 2010.

“Doss v. Bernal: Ending Mexican Apertheid in Orange County” by Robert Chao Romero and Luis Fernando Fernandez published by the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center in 2012.

Remembering the Bernals: Untangling the Relationship Between Race, Space, and Public Memory in Fullerton, California. CSUF Master’s Thesis by Shannon Anderson, 2023.

A People’s Guide to Orange County. Lewinnek, Elaine, Gustavo Arellano, and Thuy Vo Dang. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2022.