The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Great Depression, Natural Disasters, and How the New Deal Benefited Fullerton

Following the stock market crash of 1929, the most significant problem facing Fullerton was the Great Depression.

Local groups like the American Legion operated a soup kitchen which offered food and (limited) lodging. Another soup kitchen was operated by the Maple School PTA.

In 1932, Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt defeated Republican Herbert Hoover in a landslide victory, becoming President of the United States. California, which had long been a Republican state, went blue for the first time in years, although a majority of Fullertonians voted for Hoover. The election was seen as a national repudiation of Hoover’s failure to improve the economic conditions of the Great Depression.

Roosevelt’s first 100 days of office in 1933 were filled with sweeping legislation aimed at combating the Great Depression.

Roosevelt called it the New Deal. At the time, unemployment had reached 25 percent—the highest in US history so far. Federal programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) were created to give people jobs, and to simultaneously build up the country’s infrastructure—new roads, dams, parks, public buildings and more were built.

The WPA alone gave over 8 million unemployed Americans jobs in its 8-year existence.

These government programs were not just for laborers. Artists, writers, actors, and musicians were also employed by the WPA to give folks not just jobs, but also hope and beauty in difficult times.

Today, nearly a century later, Roosevelt’s New Deal is primarily remembered in history textbooks and school curricula. But there is another way to remember its legacy—by recognizing the New Deal projects that still exist right where we live.

The city of Fullerton was a major recipient of New Deal funding and projects, many of which still exist today and have become some of the most iconic features of our local landscape. But first, a bit of context.

As if the Great Depression wasn’t hard enough to endure, Fullertonians also faced two major natural disasters during the 1930s.

First came the devastating Long Beach Earthquake of 1933, which caused over $50 million in damage and killed 120 people throughout the region, injured thousands, and caused tens of millions in property damage.

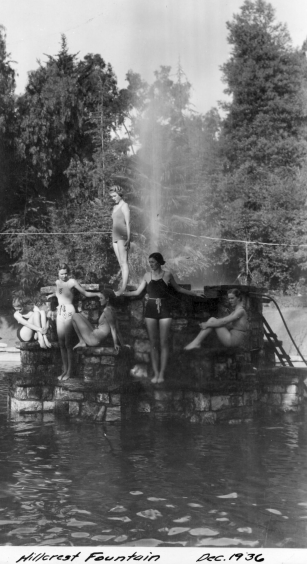

Some refugees from the earthquake took up temporary residence in their cars at Hillcrest Park and at the American Legion hall, where they were provided food and shelter by local volunteers and the Red Cross. The Izaak Walton Lodge was also opened to those who had fled the quake.

“Fullerton American Legion members continued to feed more than 100 persons at each meal at the Legion hall,” the News-Tribune reported. “Many of this group are lodged in Fullerton homes or camping in the park and are nearly without funds, their homes demolished or unsafe for occupancy in Long Beach, Compton, Bellflower and other points.”

Mrs. Clarence Spencer on W. Orangethorpe took in 27 quake refugees.

Most Fullerton buildings escaped damage, although a chimney fell at the California Hotel, crashing through the roof of the cafe kitchen and half filling it with bricks and shattered building materials. Thankfully, no one was there at the time. The old elementary school on Wilshire and Lawrence (now a parking lot) also experienced some damage, causing it ultimately to be condemned.

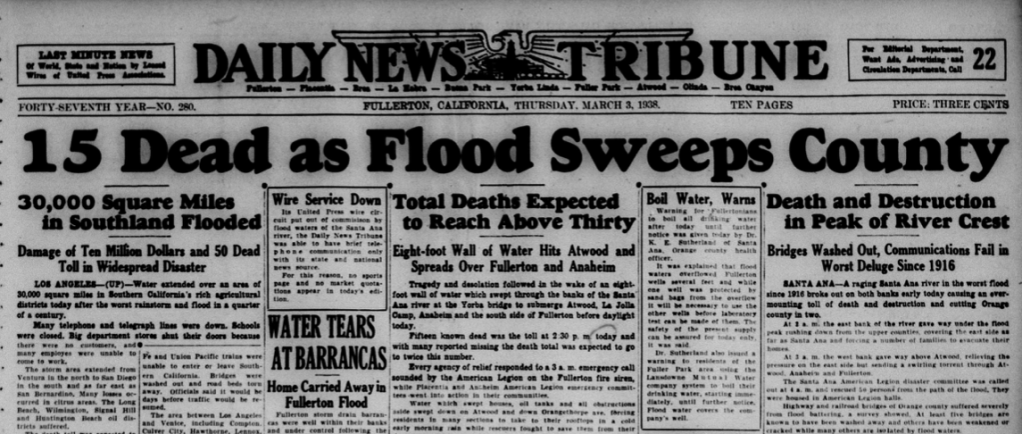

Then came the 1938 flood.

The story of the flood is all the more tragic because local residents had twice voted down bonds that would have allowed for flood control infrastructure.

In 1931, Fullerton residents voted to enter the Metropolitan Water District, which would give the city access to water from the Colorado River via aqueduct. In 1933, the Orange County Water District was created.

In 1935, over six million dollars of federal funds (around $138 million today) were planned for a large scale Orange County flood control plan–to build the Prado Dam, as well as channelize much of the Santa Ana river. These federal dollars were contingent on local voters approving a bond measure to supplement the federal relief funds.

A well-funded opposition campaign which called the bonds a waste of taxpayer dollars resulted in the bond issue, and therefore the federal relief dollars, being lost. Voters actually had two chances to approve the bonds, but they voted them down twice.

Unfortunately, because the flood control measures were not passed, a few years later the 1938 flood would devastate local communities. It would take a natural disaster for people to understand the need to invest in this infrastructure.

In 1938, following severe rainstorms, the Santa Ana river overflowed its banks and caused widespread damage, killing over 50 people.

“Water extended over an area of 30,000 square miles in Southern California’s rich agricultural districts today after the worst rainstorm and flood in a quarter of a century,” the News-Tribune reported.

Property damage was estimated at $10,000,000, and thousands were marooned by flood waters.

“Tragedy and desolation followed in the wake of an eight foot wall of water which swept through the banks of the Santa Ana river at the Yorba bridge to submerge Atwood [Placentia], La Jolla Camp, Anaheim and the south side of Fullerton,” the News-Tribune reported. “Water which swept houses, oil tanks and all obstructions aside swept down on Atwood and down Orangethorpe ave. forcing residents in many sections to take to their rooftops in a cold early morning rain while rescuers fought to save them from their dangerous quarters.”

The flood waters extended all the way to downtown Fullerton.

Local relief efforts were spearheaded by the Red Cross, local police and firefighters, and the American Legion. Shelters were set up in Hillcrest Park and St. Mary’s church for flood refugees.

Tragically, many of the victims of the flood were Mexican Americans living in citrus camps of south Fullerton, north Anaheim, and Placentia.

“Seven bodies were reported recovered at Atwood this morning. according to Chief of Police Gus Barnes at Placentia,” the News-Tribune reported. “Rescue workers with motorboats, rowboats and lifelines attempted to cross the river to the shattered cottages in which several hundred Mexican agricultural workers made their homes.”

The floods damaged or destroyed hundreds of homes, bridges, barrancas, and other infrastructure.

The 1930s were pretty rough.

“Because of these disasters, nearly every single community in Orange County was profoundly impacted by the New Deal,” Charles Epting writes in The New Deal in Orange County. “Dozens of schools, city halls, post offices, parks, libraries, and fire stations were built; roadways were improved, and thousands were given jobs.”

Out of the tragedies of the 1930s, here’s how the New Deal benefited Fullerton.

“With a population of just over 10,000 in 1930, Fullerton was one of the largest cities in Orange County at the time of the Great Depression. Relief projects were numerous. It is probable that Fullerton received more aid than any other Orange County city,” Epting writes. “What is also unique about Fullerton is that nearly all of its New Deal buildings are still standing and preserved as local landmarks.”

Maple School (244 E Valencia Dr): This school was retrofitted and expanded following the 1933 earthquake. It was partially funded by the Public Works Administration (PWA). It’s an example of Art Deco architecture. Plans were drawn by architect Everett E. Parks.

Wilshire Junior High School (315 E Wilshire Ave): Originally constructed in 1921, it was reconstructed and expanded during the 1930s with PWA funds. The style is Deco/Greco. Now it’s the School of Continuing Education.

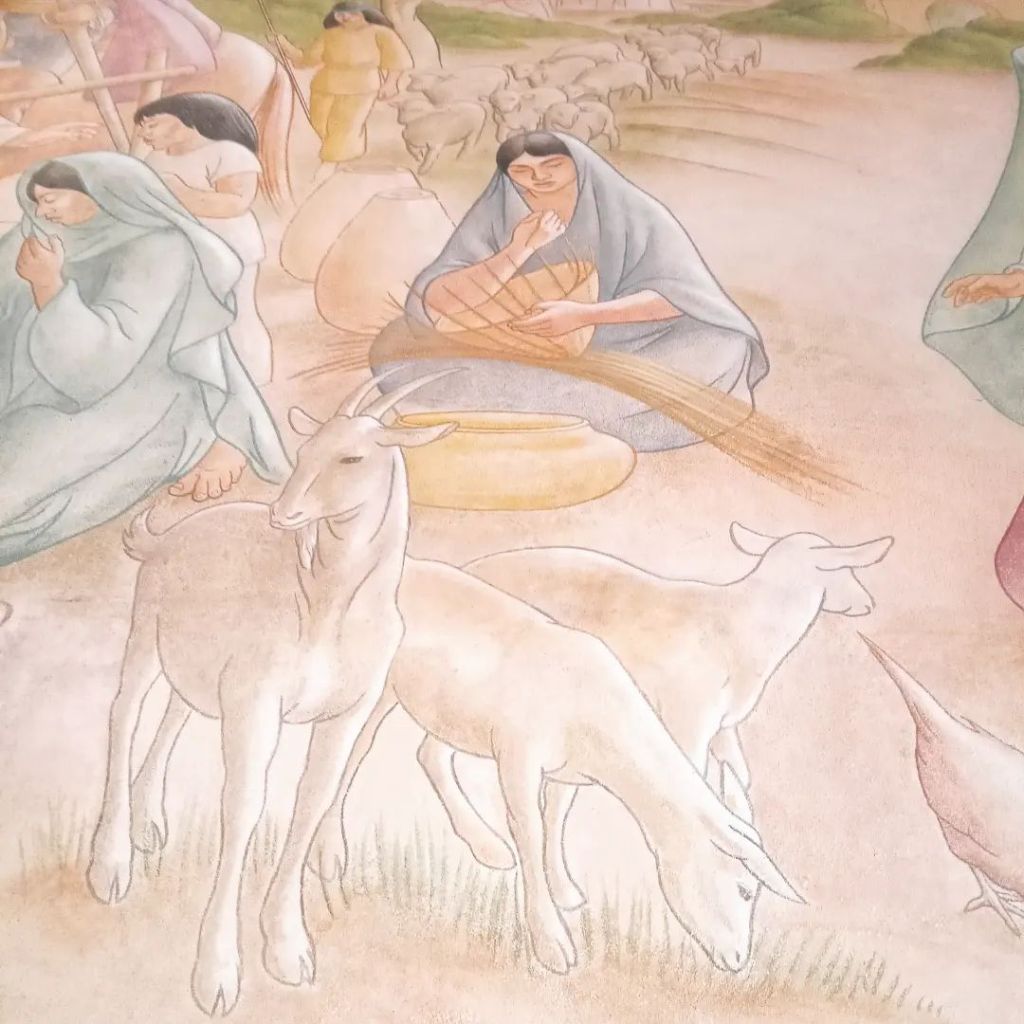

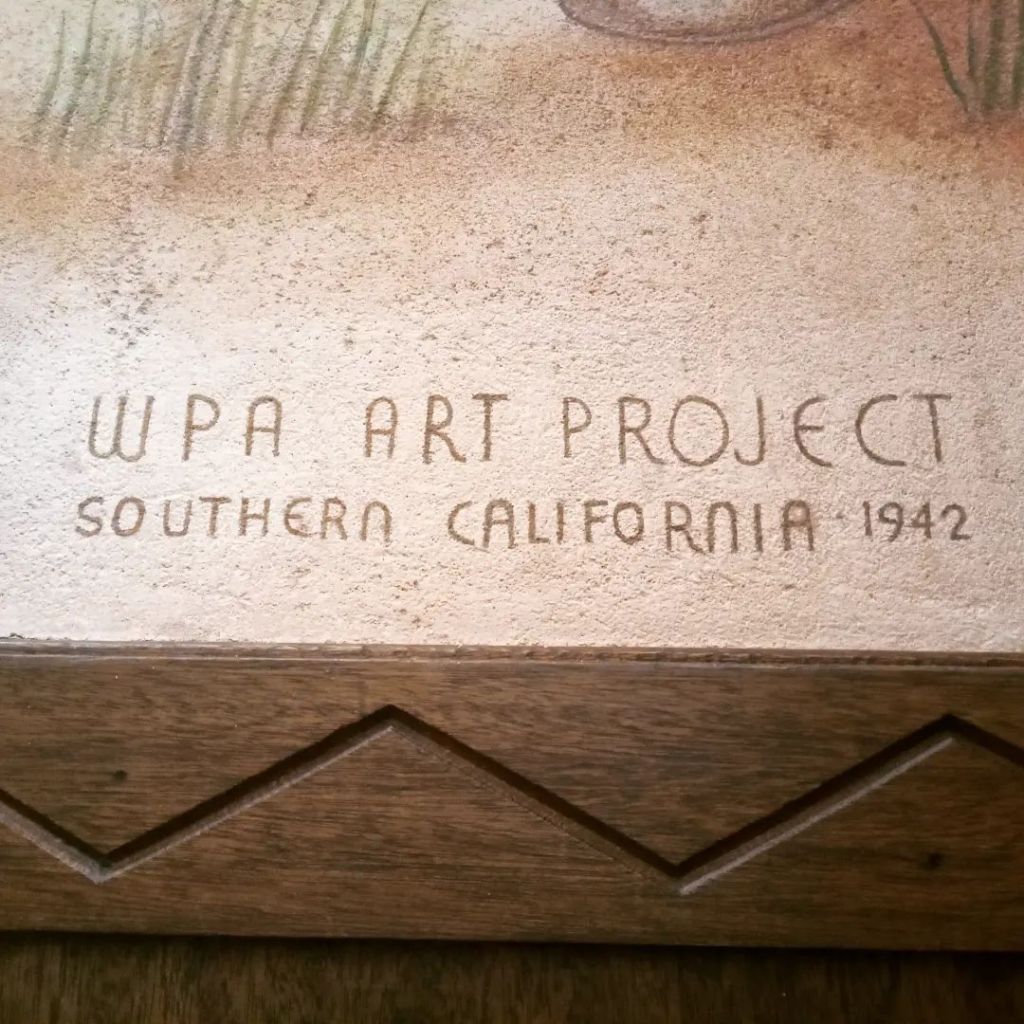

“Pastoral California” mural on High School Auditorium (201 E Chapman Ave): Giant fresco painted by Charles Kassler under the Public Works of Art Project in 1934. Spanning 75 feet by 15 feet, the mural is unmatched in size and scope. One of the two largest frescoes commissioned during the New Deal. More on this later.

Fullerton College (321 E Chapman Ave): In 1935, Fullerton architect Harry K. Vaughn teamed up with landscape architect Ralph D. Cornell to create a general plan for the new campus, to be partially funded by the WPA and the PWA. The first building was the Commerce Building, next was the Administration and Social Sciences building, then the Technical Trades building.

Fullerton Museum Center (301 N Pomona Ave): Fullerton’s first public library was an Andrew Carnegie-funded library built in 1907. Years of wear (and the 1933 earthquake) necessitated a re-building. In 1941, the Carnegie Library was demolished, and a new library was re-built by WPA workers. The building was dedicated in 1942. A new library (on Commonwealth) was built in 1973, and the Fullerton Museum Center has occupied the building since 1974.

Post Office (202 E Commonwealth Ave): The first federally-owned building in Fullerton, it was built in 1939 and funded by the Department of the Treasury, and built by crews of local workers. This post office also contains the mural “Orange Pickers” by Paul Julian, funded by the Treasury Department Section of Fine Arts. Paul Julian went on to have a very successful career at the Warner Bros. studios animating Looney Tunes shorts.

Police Station/Former City Hall (237 W Commonwealth Ave): The impressive Spanish Colonial Revival building is now home to Fullerton’s police department. Designed by architect George Stanley Wilson, the building was completed in 1942. One of the most distinctive features of the building is its extensive tile work.

“The History of California” Mural in the Police Station: A three-part mural for which the WPA’s Federal Art Project commissioned artist Helen Lundeberg to paint in 1941. The mural depicts everything from the landing of Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo in San Diego in 1542 to the birth of the aircraft and movie industries in Los Angeles in roughly chronological order. Here are some photos I recently took of the mural. Unfortunately, you have to make an appointment with the police department to see this public work of art:

Hillcrest Park (1200 N Harbor Blvd): The amount of work done in Hillcrest Park during the New Deal was staggering, with projects being funded and constructed by the CWA, WPA, RFC, and SERA. Much of Hillcrest Park’s landscaping was done during this era, like the excavation of the “Big Bowl.” Perhaps the most iconic feature of Hillcrest Park is the Depression-era stonework that runs throughout the Park. Today, Hillcrest Park represents the finest example of a WPA-era park in Orange County and has enjoyed federal recognition since 2004, so the structures are safe.

Amerige Park (300 W Commonwealth Ave): A wooden grandstand and stone pilasters were built at the baseball field in 1934. The grandstand was destroyed by a fire in the 1980s, but the flagstone pilasters remain.

Pastoral California: The Story of a Mural

“Pastoral California,” the 75-foot long fresco mural on the side of the Auditorium at Fullerton Union High School was painted in 1934, during the Great Depression, painted over by order of the Board of Trustees in 1939, and restored 58 years later in 1997. The story of this mural, what it depicts, why it was painted over, and finally restored, is one worth reflecting upon.

In addition to building projects, the WPA also commissioned murals in cities across America, including Fullerton, in an effort to give people not just jobs, but a sense of hope and beauty in difficult times. Perhaps the most famous of these murals is “Pastoral California,” one of the two largest frescoes commissioned by the WPA.

Charles Kassler, who had studied art at Princeton, traveled extensively, and apprenticed under a fresco painter in France, completed “Pastoral California” in 1934. Kassler had only one hand. He’d lost the other in a high school chemistry accident. He was married to famous Mexican singer Luisa Espinel, who was the aunt of pop superstar Linda Ronstadt.

Kassler clearly did local history research before painting the mural. It depicts a Spanish/Mexican southern California. From the 1700s to 1821, California was controlled by Spain. From 1821 to 1848, it was controlled by Mexico. Around that time, the United States decided it was their “Manifest Destiny” to control California, so they took it through a war of conquest, the Mexican American War. Kassler, however, chose to depict not an Anglo-American California, but a Spanish/Mexican one.

The mural depicts historical figures like Jose Antonio Yorba, a large landowner whom Yorba Linda is named after. In the background is Mission San Juan Capistrano. To the right is Pio Pico, the last Mexican governor of California. Most of the figures are Latinos doing everyday activities: washing clothes, riding horses, eating together.

1930s LA art critic Merle Armitage praised the mural: “Kassler has adhered not only to the beautiful traditions of pastoral California, but at the same time has also borne in mind the splendid Spanish architecture, and, lastly, created a beautiful fresco of amazing vitality and freshness of viewpoint.”

Dr. H. Lynn Sheller taught English and History at Fullerton College in 1934, at the time “Pastoral California” was painted. “I watched him [Charles Kassler] put the mural up there,” Sheller recalled in an interview for the Fullerton College Oral History Program, “I would visit him day after day as he was working…the feature of a fresco is that the paint is mixed in with the plaster, thus it is supposed to be permanent.”

But not everyone was happy with Kassler’s mural.

An article from August 30, 1939 in the Fullerton News-Tribune entitled “High School Mural Doomed; Paint it Out, Trustees Order” reads:

“Fullerton Union high school’s much discussed and criticized mural which covers the outside west wall of the auditorium received its death sentence at the hands of district trustees last night who ordered the wall paint sprayed to cover the painting.

This mural is approximately 75 feet long by 15 feet high with its huge figures of horses and riders and other human forms depicting early California days has been a mooted [sic] point since its completion several [five] years ago by the artist Kassler as a federal art project.

Most occupants of the high school will shed no tears over the decision of the board; it was indicated today as the lurid colors and somewhat grotesque figures have apparently failed to capture popular fancy.”

C. Stanley Chapman, son of Fullerton’s first mayor, Charles C. Chapman, and a city council man himself, was one of the ones who “shed no tears.” In an interview for the Cal State Fullerton Oral History Program, Chapman said: “The [mural] down there at the school was almost as absurd [as the one in the post office]. They were painted by that WPA business and the painting did not go with the architecture of the school. It was a great relief when they did paint them out. They were not an artistic addition to the building by any means”

The college student interviewing Chapman replied that superintendent Louis Plummer disagreed with this assessment: “Mr. Plummer seemed to think they were nice although he did not say so. He simply quoted a long article from the Los Angeles Times art critic who said they were lovely and truly representative and that the colors were beautiful. Mr. Plummer ends that little discourse by saying, ‘and they were painted over,’ as though he was disappointed.”

Chapman repied, “Oh, yes, the colors were good. But I have forgotten what the theme was.”

The interviewer reminded him, “Mexican entertainment; with the horses, and the children playing.”

Chapman replied, “Oh, yes, Well, the colors were nice. I don’t know. I was never involved in the school board or anything like that.”

Why was the mural painted over? I have heard some speculate that it was because some of the women depicted in the mural had naked, exposed breasts. However, I have seen no evidence that there was any nudity in the mural. In the mural as it exists today, and in every photo I’ve seen, the women are clothed. Some of them have big breasts, but that hardly seems justification for painting over the whole mural.

“It wasn’t until we had a group of trustees in here who were negatively inclined, that it was painted over,” Sheller remembers. When asked why it was painted over, Sheller said, “Some people felt it was vulgar or gross in some way. It simply showed the Mexican women as they were probably attired at that time. They were very bosomy women. I don’t think that we would feel that there was anything wrong with it. I never felt there was.”

But others have a different view, one I believe makes more sense, given the social context of 1930s Fullerton.

“It was too Mexican, that’s why,” speculated Charles Hart, 75, who was a student at the high school and remembers the mural before it was covered up. “The school board didn’t want to leave the impression that this town was anything else but Anglos. Too extreme for them, I guess.”

Hart said this in a 1997 Los Angeles TImes article.

The decision to paint over this mural probably had to do with its subject matter. It celebrated Mexican culture at a time of heightened racism against Mexicans, and when Mexicans lived in segregated communities, attended segregated schools, and were often forcefully and illegally deported back to Mexico during the Great Depression.

I have written about this at some length in an article entitled “The Roots of Inequality: The Citrus Industry Prospered on the Back of Segregated Immigrant Labor.”

“Pastoral California” remained painted over for six decades years until, in 1997 it was restored, thanks to a massive community effort. I was actually attending Fullerton High School at the time. Some of my friends, art students, helped with the restoration. I remember thinking, even then: Why would anyone have painted over something so beautiful?

A Tale of Two Cities

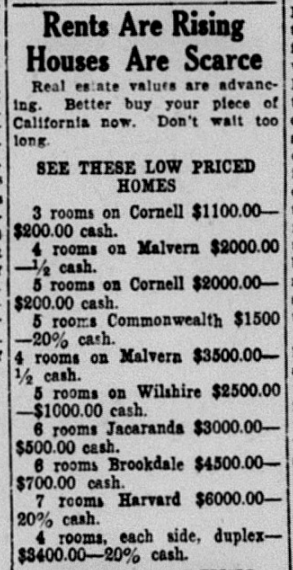

In the 1920s, Fullerton experienced a housing boom, with numerous new subdivisions being built. With the advent of the Great Depression, much new construction stopped, leading to a housing shortage.

To help with the housing situation, the New Deal established entities like the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which offered affordable home loans and other assistance to homeowners and home buyers.

In the 1930s, Fullerton was really a “Tale of Two Cities” divided along racial lines. Most neighborhoods had racially restrictive housing covenants that prevented non-whites from renting our purchasing property.

There was really only one relatively small neighborhood–the Truslow/Valencia neighborhood where Latinos and African Americans could purchase homes.

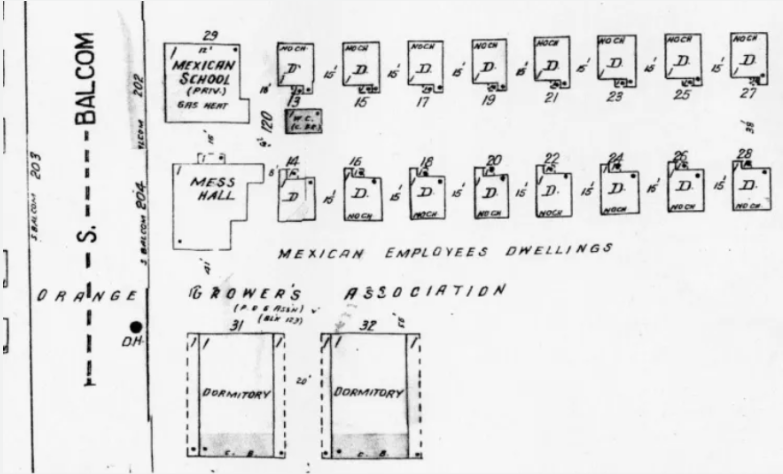

The majority of Latinos living in Fullerton in the 1930s lived in citrus work camps. There was one near downtown at Balcom and Pomona (Campo Pomona), another one near Valencia Ave., and then there were several “colonias” (little communities) on the Bastanchury Ranch (that is, until the mass deportation of 1933).

The presence of a large Mexican labor force in the Anglo-dominated towns of Orange County, including Fullerton, led to policies of segregation and second class citizenship for the Mexican workers and their families.

“Mexicans in citrus towns were invariably the pickers and packers; and consequently they were poor, segregated into colonies or villages, and socially ostracized, even though they were economically indispensable to the larger society,” historian Gilbert Gonzalez writes in Labor and Community: Mexican Citrus Worker Villages in a Southern California County, 1900-1950. “The class structure in rural areas has generally divided along lines of nationality. At the top, the growers, native-born white; at the bottom, the foreign-born migrants, or his or her children.”

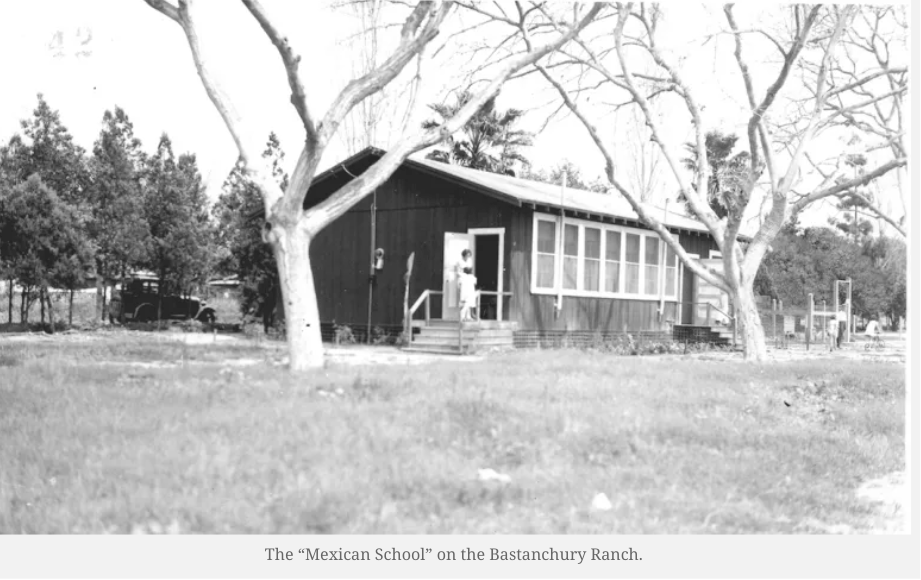

Segregation and structural inequality also extended to education. In the camps, there were schools built exclusively for the Mexican children.

“Segregated schooling assumed a pedagogical norm that was to endure into the fifties and parallels in remarkable ways the segregation of African Americans across the United States,” Gonzalez writes. “By the mid-1920s, the segregated schooling process in the county expanded, matured, and solidified, was manifested in fifteen exclusively Mexican schools [throughout Orange County], together enrolling nearly four thousand pupils. All the Mexican schools except one were located in citrus growing areas of the county…Distinctions between Mexican and Anglo schools included differences in their physical quality.”

There were at least two “Mexican Schools” in Fullerton–one on the Bastanchury Ranch and another in Campo Pomona.

Unlike at the white schools, curriculum at the Mexican schools were generally limited to vocational subjects, and junior high was considered the end of schooling for most students, many of whom accompanied their parents in the groves and packinghouses.

One woman who taught at these segregated “Mexican Schools” was Arletta Kelly. In an interview for the CSUF Oral History Program, Kelly described her struggle to convince her colleagues that Mexican students had the same potential as whites.

“Some of my colleagues here would laugh at me and say, ‘Are you a wetback?’” she said.

In addition to educating children, teachers at the “Mexican schools” also taught “Americanization” classes to adults—to assimilate the workers to American society.

“Whereas the Americanization programs in the local villages appear unique, in reality they reflected a generalized expression for the eradication of national cultural differentiation across the United States,” Gonzalez writes.

Under the California Home Teachers Act of 1915, Americanization programs focused on the teaching of English.

Louis E. Plummer, superintendent of the Fullerton High School District, staunchly supported Americanization because in his view the persistence of “Little Italys, Little Chinas, Little Mexicos” stifled the development of a “homogeneous people.” In particular, the failure of Mexicans to live in a “model way” or as “first class citizens,” which was produced by “a hangover of lazy independence” made it imperative that rather than merely learning skills, Mexicans had to learn and live within the fundamental cultural norms of the United States. His perspective summarized much of the Americanization spirit in the larger community during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“Many a surviving villager resident has not forgotten that in their youth the ‘Anglos never wanted to have anything to do with us except that we pick their oranges.’ Such was the nature of the dominant contours in the Mexican and Anglo social relations in the citrus towns,” Gonzalez writes.

Mass Deportation of Mexican Immigrants

With unemployment on the rise during the Great Depression, immigrants (as always) made a convenient scapegoat and there were calls to restrict immigration.

The Great Depression proved disastrous for the Bastanchury family, owners of “the largest orange grove in the world.” Unable to pay their debts, the Bastanchury Ranch went into receivership, and lost most of their property.

According to Druzilla Mackey, a teacher in the Mexican camp schools, “The American Community…felt that the jobs done so patiently by Mexicans for so many years should now be given to them. ‘Those’ Mexicans instead of ‘our’ Mexicans should ‘all be shipped right back to Mexico where they belong’…And so, one morning we saw nine train-loads of our dear friends roll away back to the windowless, dirt-floor homes we had taught them to despise.”

What she is referring to is a mass deportation of nearly all of the Mexican workers on the Bastanchury Ranch in the early 1930s. This deportation was part of a much larger deportation effort across the United States, which is described at length in the book Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s.

“Outside of the community, the Mexican became the scapegoat,” Gonzalez writes. “In 1931 and 1932, local and county governments caught up in the drive across the Untied States to deport Mexicans sought to cut budgets through repatriating Mexicans. Induced through threats of relief cutoff sweetened with an offer of free transportation, about 2,000 left Orange County.”

Many of those deported were actually American citizens. A few years ago, I had the privilege of interviewing Fullerton resident Manuel Rivas Maturino, who was born on the Bastanchury Ranch, and remembers the experience of “repatriation.”

“All of the Mexican camps on the ranch have been eliminated and all American labor is being used with 28 houses on the ranch now filled with regular employees, nearly all of whom have been continuously on the payroll since last April,” the News-Tribune reported in 1933. “Nine carloads of Mexicans, including 437 adults and children–mostly children–were deported from Orange county today to points on the Mexican border, where they were to re-enter their native country.”

Despite these mass deportations, local growers realized that they needed Mexican workers to harvest the orange crop, and so continued to utilize the labor of immigrants.

The 1936 Citrus War

Throughout the 1930s, many labor strikes occurred throughout California. Mrs. Reba Crawford Splivalo, state director of social welfare, told an audience of around 300 in the Fullerton high school auditorium in 1933: “I see in the sky the signs of rebellion. I am not crying ‘wolf, wolf.’ I am giving a warning. If the present economic situation is to survive the needs of the underprivileged must be met. Capital and labor must find a common meeting ground.”

In his book Endangered Dreams: The Great Depression in California, historian Kevin Starr writes, “Between January 1933 and June 1939, more than ninety thousand harvest, packaging, and canning workers went out on some 170-odd strikes.”

That was just agriculture. Major strikes in other industries, such as the 1934 West Coast waterfront strike, rocked California’s major coastal cities.

These strikes were massive and sometimes erupted into violent street fights between strikers and police. Late in 1934, streetcar workers in Los Angeles went on strike. Closer to home, dairy workers in Orange County went on strike.

Those organizing labor strikes were often accused of being communists.

In 1936, the sleepy agricultural towns of Orange County, including Fullerton, saw a labor strike unprecedented in its intensity–revealing long-simmering tensions.

“Warning to citrus growers that they might expect communistic activities in this district as soon as the valencia season opens and methods of combating the agitation was given by H.O. Easton, packinghouse manager, at the regular meeting of the chamber of commerce here yesterday,” the News-Tribune reported in 1935.

Easton argued that local cities should pass anti-picketing ordinances (Fullerton already had one).

“He told citrus growers that they should impress upon workers they hire that any agitation is the work of communists attempting to start trouble among men employed in this district,” the News-Tribune reported.

Special guards were requested to protect packinghouses.

The truth is that most rank-and-file workers were not communists. They just wanted better working conditions. However, some of the organizers were, in fact, communists.

“Charles McLauchlan of Anaheim, self-admitted worker in the interests of the communist party, was arrested late yesterday afternoon at Placentia by Chief of Police Gus Barnes and charged with violation of the city ordinance prohibiting distribution of circulars and handbills without a license,” the News-Tribune reported.

McLauchlan was accused of selling copies of the Western Worker, a labor newspaper, to Mexican citrus workers in Placentia. He was also selling copies of a booklet, The Fascist Menace in the U.S.A.

If the strike organizers were sometimes communists, the growers and the legal system that sided with them often acted like fascists, cracking down hard on those trying to organize to better their lot.

In 1935, there was talk of strike among the remaining Mexican workers, to improve pay and working conditions.

Ricardo G. Hill, Mexican consul at Los Angeles, addressed a crowd of 2,500 Mexican workers in Anaheim, urging them not to strike, and to wait until next picking season to attempt to form a union. Earlier in the day, Hill had met with local packinghouse managers who “said they would not recognize the rights of the Mexican pickers to organize and demand a minimum wage of $2.25 a day and that managers threatened to import Filipino workers to Orange County to do the work, if necessary.”

It’s ironic, though not surprising, that growers and packinghouse managers opposed worker efforts to organize for better wages and working conditions because organizing for a better return was exactly what the growers and packinghouses did. They pooled their resources in the form of the California Fruit Growers Exchange (or Sunkist) to fix prices and make the most money.

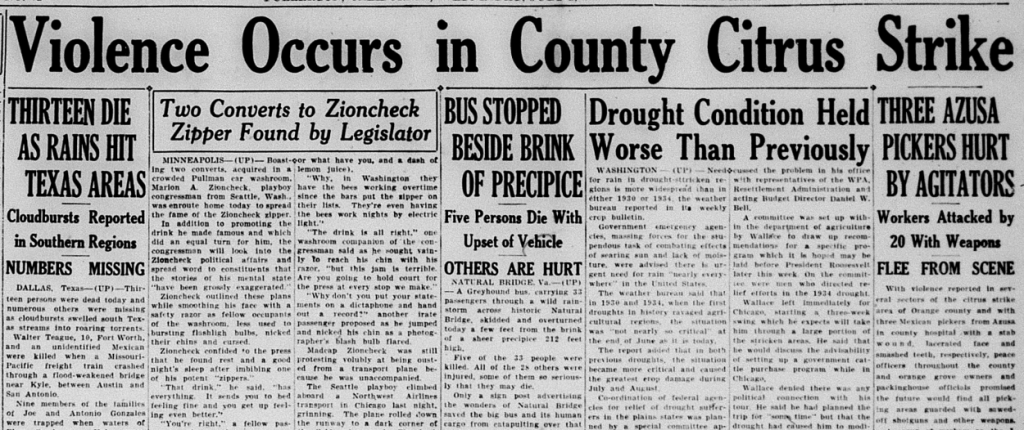

In his 1972 USC doctoral dissertation entitled The Orange County Citrus Strikes of 1935-1936: The Forgotten People in Revolt, Louis Reccow called it, “the largest and most violent citrus strike of the depression.”

In March strike leaders sent the growers of Orange County two lists of demands calling for better pay and working conditions as well as union recognition–demands which the growers ignored.

On June 11, as many as 2,500 workers went on strike.

The Fullerton News-Tribune characterized the strike leaders as outside agitators and communists. Police officers were organized to “protect” those who wanted to work from “threats of agitators.”

Sheriff Logan Jackson deputized hundreds of men. The American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars pledged their assistance to police and the growers.

During the strike, pickers who did not participate were escorted to work by armed guards.

“Police, deputy sheriffs and specially recruited deputies of police, sheriff and constables were in the field this morning keeping a constant watch for appearance of agitators,” the News-Tribune reported.

“Scab” crews and white students were hired to pick the oranges.

“From Placentia high school and Fullerton district junior college, scores of youths went today to orchards to take the place of the strikers,” the News-Tribune reported.

The first instance of “violence” occurred in Anaheim when striker Virginia Torres bit a police officer on the arm.

“Two hundred angry Mexican women spurned on the citrus picker’s strike today as the first riot call of the strike sent a score of officers into Anaheim early this morning to quell a disturbance led by the women,” the News-Tribune reported.

Torres and others were arrested.

Elsewhere, in Brea, strikers were arrested on flimsy grounds ranging from traffic violations to trespassing.

Charles McLaughlan was arrested on trespassing charges in the Mexican worker camp on Balcom in Fullerton. Not long after McLauchlan’s arrest, some striking orange pickers were evicted from their homes in the worker’s camp.

Conflict between strikers, scabs, and law enforcement sometimes flared into violence.

“During the month of July [1936], northern Orange County experienced a kind of civil war,” Reccow writes. “Increased picketing, violence, armed deputies by the score, vigilante attacks, mass arrests and trials, shoot-to-kill orders, calls for State interference, along with California State Federation of Labor and federal government involvement–all contributed to the situation.”

“With violence reported in several sectors of the citrus strike area of Orange county and with three Mexican pickers from Azusa in county hospital with a stab wound, lacerated face and smashed teeth, respectively, peace officers throughout the county and orange grove owners and packinghouse officials promised the future would find all picking areas guarded with sawed off shotguns and other weapons,” the News-Tribune reported.

“All Orange country was under heavy guard today as Sheriff Logan Jackson, following yesterday’s violence, began deputizing 170 additional special deputies to protect every picking crew and packinghouse in the county,” the News-Tribune reported.

The increased police presence did little to quell the conflict. In one day at the height of the strike, 159 Mexican strikers were arrested on charges of “rioting.”

As conflict and occasional violence continued, Sheriff Jackson issued a “Shoot to Kill” order to his men.

“New special deputies were being added rapidly to the sheriff’s office staff, which numbers 300 to 400 now, and 20 more California highway patrol officers were rushed here today from Los Angeles county to be added to 35 or 40 already on duty,” the News-Tribune reported.

In La Habra, 40 or 50 families were evicted from their homes on ranch property for participating in the strike.

In the conflict, the strikers had weapons like rocks and clubs. The police had tear gas guns, hand grenades, rifles, and shotguns.

Sometimes the police would arrest and jail Mexicans before any crime occurred.

“A strange parade it was from Placentia ave, at Pointsettia, near Anaheim, yesterday afternoon as California highway patrolmen and the sheriff intercepted 19 carloads of Mexicans, more than 100 in all, who said they were going to Orange for a meeting,” the News-Tribune reported. “The parade, enlarged by five more carloads intercepted in a neighboring road, ended at the jail.”

On July 8 the 119 Mexicans arrested on rioting charges were arraigned in the open courtyard behind the Fullerton courthouse under heavy guard from state highway patrol officers and deputy sheriffs armed with sub-machine guns and sawed off shotguns.

A couple weeks later this large group was again transported to Fullerton.

“The Odd Fellows Temple, selected by law officials as the site of the hearing for security reasons, soon resembled an armed fortress. Men armed with submachine guns, riot guns, revolvers, and clubs guarded all exits and entrances,” the News-Tribune reported.

Part of the reason the strike continued was because of the growers’ insistence that the strike was not a result of legitimate grievances, but rather part of some nefarious communist plot.

“Dr. W.H. Wickett of Fullerton, a member of the publicity committee of the growers organization, said today that the growers have definitely learned that the strike is not a walkout merely for the betterment of pickers but is directed and abetted by communist headquarters for the purpose of fomenting strife in the interests of communism,” the News-Tribune reported.

In fact, the workers’ demands, which were publicly sent to the growers well before the strike, had nothing to do with communism, and everything to do with improving pay and working conditions.

Whether growers like Wickett actually believed the strikers represented a communist threat or they were simply seeking to tarnish the strikers so as to avoid having to treat their workers better, is hard to say.

It wasn’t just the police who sought to disrupt and end the strikers’ activities. Vigilante activity also occurred.

“Wild disorder, repetition of which was promised for tonight at the same place, broke out last night about 9:15pm, near Santa Fe ave. and Melrose in the center of Placentia as 40 Americans of a vigilante committee swooped down upon a Mexican gathering and with guns, clubs and a score of tear gas bombs sent them scattering in ever direction,” the News-Tribune reported. “Reports…stated 20 to 30 Mexicans and a few of the white men were injured, cars were smashed and other damage done. Several Mexicans among the group, who had gathered on the Luis Varcas handball court for a meeting told officers they definitely recognized ‘Stuart Strathman as the supposed leader of the raid.’”

Strathman was a leading representative of the growers and packinghouses, with an office at the Chamber of Commerce.

No arrests or charges were made against any of the vigilantes.

Eventually, an agreement between the strikers and growers was reached–insuring higher wages and a few other benefits, but not union recognition.

Charges against all but 13 of the strikers charged with rioting were dismissed. Of those, 10 were found guilty and faced fines and imprisonment.

Reflecting on the strike, Reccow writes, “The strike offers a classic study in the use of anti-strike tactics: the deputizing of hundreds of growers, blacklisting, the eviction of workers from company homes, the cries that agitators and communists were responsible for the strike, vigilante attacks, the strict enforcement of an anti-picketing ordinance, the jailing of large numbers of strikers and the deportation of alien Mexican workers.”

Journalist Carey McWilliams wrote, “No one who has visited a rural county in California under these circumstances will deny the reality of the terror that exists. It is no exaggeration to describe this state of affairs as fascism in practice.”

A Socialist for Governor?!

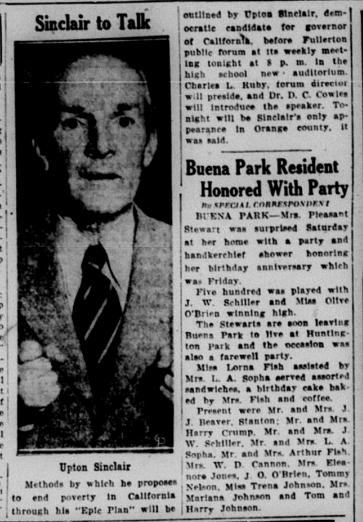

In the midst of economic hard times and labor agitation, noted author and socialist Upton Sinclair ran for governor of California. Sinclair, most famous for his 1905 novel The Jungle, which portrayed the filthy and inhumane conditions of the meatpacking industry, had spent his life writing numerous books highlighting various injustices and corruption in American life.

Sinclair had moved to Southern California in 1916 and, in addition to writing, also involved himself in politics, running for congress twice (in 1920 and 1922) as a Socialist. He founded California’s chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

In 1934, he decided to run for governor of the Golden State, this time as a Democrat. He won the party’s nomination and faced off against Republican Frank Merriam. Sinclair’s program was called End Poverty in California (or, EPIC). He wrote a pamphlet called I, Governor of California, and How I Ended Poverty, which laid out his plans and was widely distributed.

During the campaign, Sinclair came to Fullerton and spoke before a crowd of over 1,200 in the FUHS auditorium. Today, Sinclair sounds a lot like Bernie Sanders.

“The trouble in America,” Sinclair began, “is that privilege entrenched itself in government and society and brought a condition where two percent of the people control 50 percent of the wealth. Wall Street tricks to control American finance by piling up wealth on one side and beating down wealth on the other made bums of twenty or thirty million people…”

Sinclair was particularly outraged with the practice of large agricultural interests destroying “surplus” crops to keep prices up.

“Limitation of production or the destruction of food or other wealth while millions of people are in need is the very apex of economic insanity,” Sinclair said.

This practice of destroying food for the benefit of big business while people starve is what gave the title to John Steinbeck’s 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath, about farmworkers in California during the Great Depression:

“There is a crime here that goes beyond denunciation. There is a sorrow here that weeping cannot symbolize. There is a failure here that topples all our success. The fertile earth, the straight tree rows, the sturdy trunks, and the ripe fruit. And children dying of pellagra must die because a profit cannot be taken from an orange. And coroners must fill in the certificate- died of malnutrition- because the food must rot, must be forced to rot. The people come with nets to fish for potatoes in the river, and the guards hold them back; they come in rattling cars to get the dumped oranges, but the kerosene is sprayed. And they stand still and watch the potatoes float by, listen to the screaming pigs being killed in a ditch and covered with quick-lime, watch the mountains of oranges slop down to a putrefying ooze; and in the eyes of the people there is the failure; and in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath. In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.”

The backbone of Sinclair’s plan of ending poverty in California involved giving unemployed workers access to the means of production and letting them produce for themselves.

“The program…will offer land colonies and factories to the unemployed and a distributing system where the people can buy necessities at cost and thereby eliminate the middle man,” Sinclair said. “It will make production for and equal to consumption because the unemployed will produce for themselves only and will make the million in the state now leaning on charity self-supporting.”

The EPIC plan also called for a remedy to economic inequality through a revised and graduated tax system, with higher taxes on the wealthy.

Sinclair was clearly on the side of the workers. Meanwhile, the Republican Frank Merriam was on the side of business.

As is documented in his book I, Candidate for Governor, and How I Got Licked, despite his popularity, Sinclair faced formidable opposition from big business and mainstream media (including Hollywood), who ran a well-funded smear campaign against him.

The Fullerton Daily News-Tribune ran numerous articles and editorials portraying Sinclair as a dangerous radical who would bring ruin to California.

The California Real Estate association, unsurprisingly, came out against Sinclair, as did the Orange County Democratic party (just like the national Democratic Party did with Bernie Sanders in 2016).

Meanwhile, local leaders organized a parade in Merriam’s honor. And the Tribune published numerous articles which painted Merriam in a very positive light. Ultimately, Merriam defeated Sinclair. Poverty would, unfortunately, not end.

Those elected to Fullerton City Council throughout the 1930s were wealthy, white businessmen who tended to favor the status quo over any radical program proposed by Sinclair.

They were Billy Hale (orange grower), Ted Concoran (paper company owner), Thomas Gowen (rancher), Harry Maxwell (real estate developer), George Lillie (orange grower), Hans Kohlenberger (factory owner), Walter Muckenthaler (orange grower), Olie Cole, Carl Bowen, and William Montague.

It would be decades until a woman or person of color was elected to Fullerton City Council.

What Fullerton Needs Now is a Drink

Prohibition, which was enacted in 1919 with the ratification of the 18th amendment, was nearing its end. It would be repealed in 1933 by the 21st amendment. Prior to that, the Wright Act, which provided state enforcement of prohibition, was repealed by voters. Fullerton, being Fullerton, kept its local ordinances making alcohol illegal.

Even prior to the repeal, congress passed a law permitting the sale of beer with an alcohol content of 3.2 or less.

Things played out a bit contentiously in Orange County. After the passage of the Beer law, the OC District Attorney declared alcohol still illegal under a county ordinance.

“Orange county remains bone dry, regardless of the new beer bill passed by congress, District Attorney S.B. Kaufman declared in a formal opinion today,” the News-Tribune reported. “The county still had a dry ordinance and because the new beer law allowed for local control…Meanwhile, LA county board of supervisors repealed their local ordinance, thus allowing beer.”

The battle between “wet” and “dry” supporters played out locally, as Fullerton City Council considered rescinding its dry ordinance. City Council declined to take a position on the contentious matter, instead putting it to a vote of the people, who decided they needed a drink.

In short order, some Fullerton businesses began selling beer.

And with the passage of the 21st amendment, Prohibition was over.

Entertainment and Sports

To escape the troubles of life, folks went to movies at the Fox Theater.

In 1931, Fullerton hosted its first Jacaranda Festival, showing off the purple flowers of the trees that still line Jacaranda Dr. and other streets. The Festival included a pageant at the high school with a cast of 300.

In 1934, Fullerton celebrated a Valencia Orange Festival, which drew 40,000 attendees.

Locals got some excitement in 1935 when the baseball movie “Alibi Ike” starring Joe E. Brown was filmed at Commonwealth Park.

Baseball games at Commonwealth (now Amerige) Park were hugely popular. The Portland Beavers did their spring training there.

In 1937, African American Fullerton author Ruby Berkley Goodwin published a book of dramatic sketches based upon Negro spirituals, in collaboration with composer William Grant Still, whose “Afro-American Symphony” was the first to be published by an African American.

In 1938, hometown hero Arky Vaughn, a professional baseball player, played a special benefit game at Amerige Park. He hit a home run!

Fullerton celebrated its 50-year anniversary with a huge three-day program, including “a colorful historical pageant including a cast of approximately 1,000 residents” which took place in the FUHS stadium and auditorium.

In addition to the pageant and baseball games, there was a coronation ball for the Golden Jubilee queen and “Miss Columbia,” Pearl McAulay Phillips and Mary Catherine Morgan.

The pageant, called “Conquest of the Years” featured scenes from local history, from Native Americans to the expedition of Don Gaspar de Portola, Spanish/Mexican hacienda days, Basque sheepherders, the appearance of town founders the Amerige brothers, to the first buildings, schools, and churches built.

“Conquest” feels like an appropriate sentiment for how Americans at this time saw their place in history. They were the latest proud beneficiaries of a series of conquests. Today, some Americans view this aspect of our history with ambivalence, perhaps not wanting to highlight the “conquest” part. But that is, unfortunately, the best way to describe how the US came into possession of so much land, which had previous owners.

Social clubs were popular in Fullerton, including Rotary, Kiwanis, Lions, Business and Professional Women’s Club, Fullerton Junior Chamber of Commerce, American Legion, 20-30 club, Ebell Club, YMCA, YWCA, Masons, Odd Fellows, and more.

Stay tuned for my next installment “Fullerton in the 1940s!”