The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Introduction

As part of my research into Fullerton history, I have created a number of mini-histories that will eventually be integrated into a larger narrative. Some mini-histories I’ve written so far cover such local topics as Hawaiian Punch, Hughes Aircraft, Cal State Fullerton, Maple School, and more.

I have recently completed writing a history of the Fullerton Police Department. The first source I read was an official history of the department published in 2002 by the Fullerton Police Officers Association. While this gives a broadly accurate narrative and includes lots of useful facts and notable people, it leaves out anything negative about the department. I have sought to supplement this history with news articles I obtained in the Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library, and others online. Another excellent source of information was a memoir written by former Fullerton police officer Phil T. O’Brien called Bullets, Badges, and Bullshit. O’Brien, who worked for the FPD from 1961 to the early 1990s, offers some useful color to a story that might otherwise feel kind of dry.

My hope is that, by synthesizing these diverse sources, I am able to give a more well-rounded picture of the department over the years. This history is, of course, incomplete, but I’ve tried to include as much information as I could find.

Early Days

In the latter half of the 19th century, prior to the formation of the town of Fullerton in 1887, the area was sparsely inhabited by a few farming families. Anaheim had a town constable, but there was no regular law enforcement presence in the area that would become Fullerton. Crime was limited to the occasional “bandit” roaming the area between Los Angeles and San Diego.

“The only law enforcement for the area was the LA County Sheriff’s office out of downtown Los Angeles,” according to FPD’s official history. “The new settlement of Fullerton was a one-day ride on horseback for the assigned lone deputy.”

For a few years after Fullerton was founded in 1887, there was no law enforcement. Saloons and rowdiness downtown created the push for some police presence.

“A number of roughs, hailing from everywhere, make it a point to come to Fullerton every Sunday, and after imbibing a library quantity of tarantula juice proceed to paint the town a bright, brilliant, carmine tint,” the Fullerton Tribune reported in 1893. “They do this with the knowledge that we have no peace officer in this section, and accordingly they have no fear of arrest. We need a constable and a justice of the peace. Anaheim, a small village a few miles south of here, has two of each.”

Eventually, A.A. Pendergrast was appointed as the town’s first constable. Pendergrast, taking ill with rheumatism, was replaced by James Gardiner, son of pioneer farmer Alex Gardiner. Tragically, James died of pneumonia after risking his life to save a young girl during a flood in 1900. He was replaced by Oliver S. Schumacher.

In 1904, Fullerton incorporated as a city, creating an official government. The first elected town marshal was W.A. Barnes. However, he resigned that same year, overwhelmed by the workload which (at that time) included supervising all roadwork and being on duty from 7am to midnight.

City Council appointed orange and walnut grower Charles E. Ruddock to finish the term for which Barnes was elected. Ruddock was re-elected in 1906. That same year, Fullerton residents voted to go “dry”—and outlaw saloons in town, which had been (and would continue to be) a point of contention and fierce debate.

Ruddock was re-elected in 1908. He expanded the department by appointing four deputies. He “retired” in 1910, and ran (successfully) for Orange County sheriff in 1914.

In 1910, Roderick D. Stone was elected town marshal. He left in 1912 and was replaced by William French, who would eventually become a local judge. It was during French’s term that the title of “marshal” as changed to “chief of police.” William French allegedly joined the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, along with many other cops and local leaders.

In 1914, Fullerton police got their first official uniforms.

Vernon “Shorty” Myers was elected police chief in 1918. That year, the first motor cops hit the streets, riding Indian motorcycles. In 1919, a new city jail was built.

The 1920s

Arthur Eeles became police chief in 1922. A former Deputy OC Sheriff, Eells had been a sharpshooter with the 364th Infantry during World War I, surviving a mustard gas attack in France.

In 1925, Eeles was asked to resign following a local controversy involving Ku Klux Klan members conducting their own vigilante raid on suspected bootleggers. Eeles was thought to be in league with the Klan.

In the mid-1920s, the Ku Klux Klan had a large presence in Orange County, including Fullerton. Their members included police officers, city council members, judges, teachers—white protestant men from all walks of life, including many prominent community leaders.

A new chief, O.W. Wilson, replaced Eeles. An academic as well as a law man, Wilson would later go on to become a well-respected pioneer in policing, teaching at Harvard and serving as police chief of Chicago.

But he didn’t last long in Fullerton and left the same year he began. He was replaced by Thomas K. Winters, who served for two years, being replaced by James M. Pearson in 1927, who would serve for 13 years.

In those early decades, police chief turnover was quite high, likely a result of the chief having to run for re-election every two years. It appears that some time during Pearson’s term, the police chief went from an elected position to one appointed by city hall because he was the first in a series of longer-tenured chiefs.

During the 1920s, Prohibition was in full effect, and local law enforcement struggled to control bootlegging.

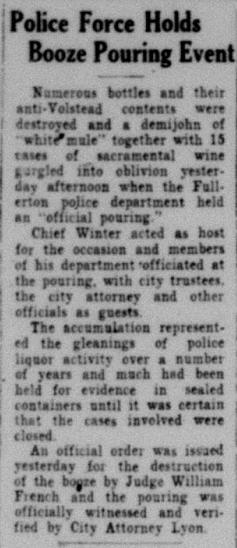

The Fullerton police department occasionally held a public “booze pouring” events in which they dumped out hundreds of gallons of illegal booze they had seized.

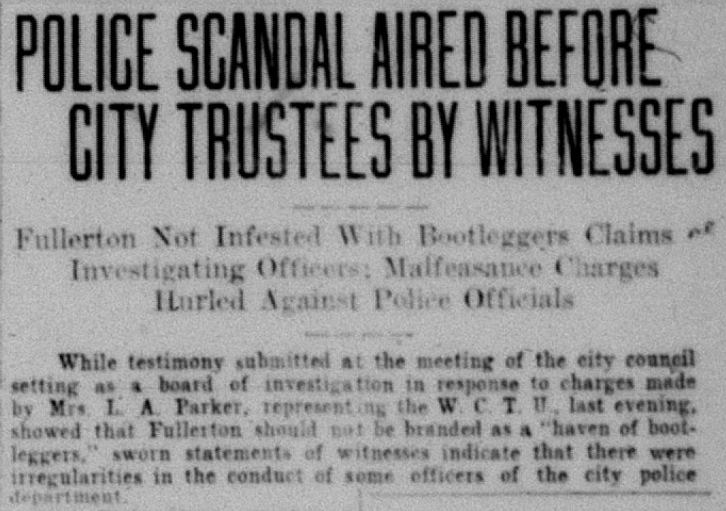

And then, in 1926, something embarrassing happened. Some Fullerton police officers were accused by another officer of stealing wine from the department’s stock of seized liquor for personal use.

After a few public hearings before City Council, the accused officers denied any wrongdoing and were not convicted of any crimes. The whole ordeal, however, caused a shake-up in the department, in which some officers were forced to resign.

Adding to the embarrassment, Fullerton City Councilmember Emmanuel Smith and beloved football coach “Shorty” Smith were both arrested and fined on liquor charges. Neither lost their jobs.

By 1929 the force was made up of eight men: Kenneth Foster, Frank Moore, RC Mills, SR Mills, JH Trezise, John Gregory, Jake Deist, Ernest Garner, and Chief Pearson.

Prior to radios and walkie-talkies, communications between the police station and officers on duty was conducted by a series of call boxes and lights atop tall buildings downtown—sort of like the Bat signal.

The 1930s

In the 1930s, the Fullerton Police Building and jail was located at 123 W. Wilshire Ave, just behind the fire station. It had three rooms—the chief’s office, the report dest, and the jail cell which had eight bunks.

In 1936, Fullerton Night School began offering a special course for police officers.

That same year, thousands of local Mexican citrus workers went on strike. Hundreds of law enforcement (including sheriff deputies and those from surrounding cities) battled with the strikers in what was the most intense labor conflict in Orange County history.

The FPD made local headlines in 1937 when Ernie Garner arrested two bank robbers who were on the run, although it was mostly just luck. One of the robbers fell asleep at the wheel and crashed the car right in front of Garner a block from the police station.

According to the official FPD history, “In the 1930s, the majority of calls was for drunks, fights, and citrus-related thefts. The patrolmen spent most of his day interacting with the downtown merchants as this was the hub of activity for the small town.”

The 1940s

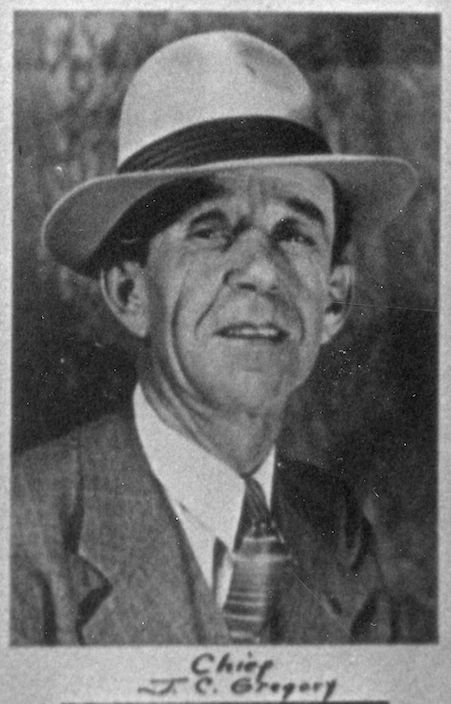

Chief Pearson retired in 1940 and was replaced by John C. Gregory, who modernized the department with a record-keeping system modeled after the FBI’s.

During World War II, the city established a Police Officer Reserve Corps, air raid wardens, a home guard, and a civil defense council.

After the war, Fullerton entered a period of rapid growth, necessitating more police officers.

“In the 1940s, the type of calls for service changed dramatically. Crime became more frequent as did the instance of violence. The calls for service started to include robberies and burglaries,” according to the official police history. “Traffic accidents were also on the rise with the influx of the population. The small justice court which was held in the city council chambers was outgrowing the facility. The municipal court system was set up to relieve the pressure of the individual justice courts throughout the county.”

In 1941, Fullerton celebrated the completion of a brand new city hall on W. Commonwealth and Highland Ave. The Spanish-style WPA building also housed the police department. Today, it is completely occupied by the police.

The 1950s

In 1951, police chief John Gregory retired and was replaced by Ernest E. Garner, who had served in the police department since 1928. The department had 21 employees.

In the 1950s, as the city continued to grow, the first police radio cars were put into service.

In 1955, the Fullerton Police Benefit Association (a sort of proto-union) was formed to give services to officers, including loans, insurance, and to promote social activities.

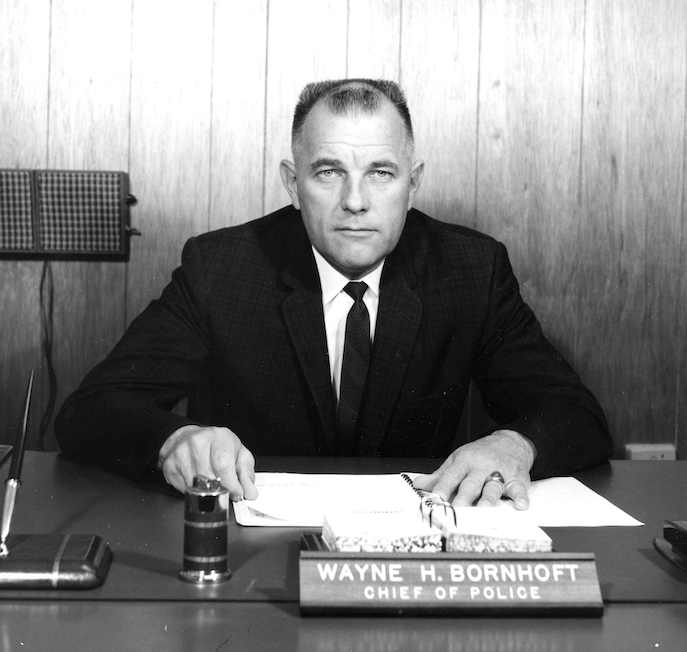

Chief Garner retired in 1957 and was replaced by Wayne Bornhoft, who would serve for many years and leave an indelible mark on the department. Today, the Fullerton Police Station is named in his honor.

Bornhoft was instrumental in establishing the Fullerton Police Training School in 1960. He served as President of the California Peace Officers Association, and was appointed by governor Reagan to the California Council on Criminal Justice.

According to O’Brien, Chief Bornhoft “never left any doubt in anyone’s mind was to who was in charge of the Fullerton Police Department. He was an authoritarian figure who ruled with an iron fist.”

Fullerton hired its first female police officer, Geraldine K. Gregory, in 1959. She worked in the Investigation Division in cases involving juveniles and women.

That same year, 1959, the Fullerton Police Training Academy was formed.

The 1960s

In the 1960s, the Fullerton Police Benevolent Association became more like a real union, with its president being the chief negotiator with the city regarding salaries, benefits, and working conditions.

In response to concern over increased recreational drug use, the FPD established a narcotics bureau in 1967. Ironically, according to officer O’Brien, the drugs of choice for Fullerton Police were alcohol and steroids.

Fulleton in the 1960s was a pretty conservative town. Officer O’Brien, who was hired in 1961, reflected the conservative establishment’s disdain for the hippie and counterculture of the era.

“Long hair on a male soon became a reason for a shakedown,” O’Brien writes. “Probable cause for a car stop, a pedestrian check, or a pat-down search for drugs or weapons was often listed in reports as simply, longhair.”

O’Brien gives a fascinating account of clashes between police and hippies in the late 1960s at Hillcrest Park, which had become a popular gathering place for young people, rock concerts, and recreational drug use.

“The bowl area became a gathering place for dirt-bag hippies and dopers,” O’Brien writes. “They soon began homesteading the park and made it such an undesirable place that families could no longer go there. We would run them out and make arrests whenever possible, but the situation continued to worsen, and the numbers of troublemakers grew.

Eventually, City Council passed ordinances to close the park at night, prohibit camping, sleeping, and/or “protracted lounging.”

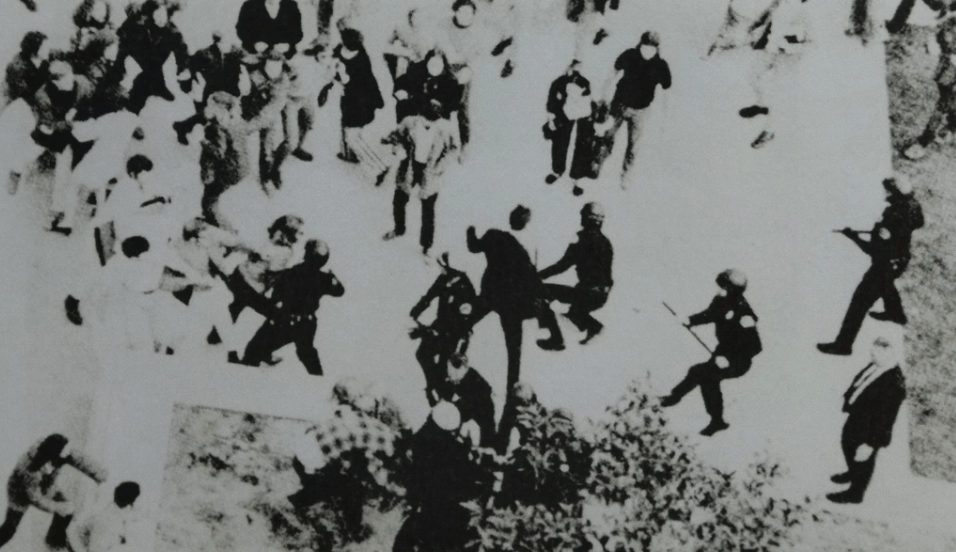

Here’s O’Brien’s account of a final confrontation between the police and the hippies in 1969 at Hillcrest Park:

“More and more dirt-bags poured into the park from all over the state. They began to refer to it as ‘The People’s Park.’

The situation came to a head one day after the news media had advertised far and wide, that on that day the Fullerton Police Department SED Squad [a precursor to SWAT] was closing down the park and would arrest anyone who failed to leave. The less than desirable inhabitants of the park looked upon this declaration as the ultimate challenge. The publicity attracted literally thousands, including newspaper reporters and television crews. Also present were the Mayor, the Police Chief, the Fire Chief, and several fire rigs, paramedics, ambulances and even a few civil rights groups.

We embarked on the task of routing this mob out of the park. They were in the trees, in the bushes, and had homesteaded every conceivable bit of space…It turned into a snipe hunt, and was soon a matter of officers in terms of two or three going after the most flagrant violators.

We were stormed with rocks, bottles, bricks, metal pipes, etc…The battle that day went on for hours, and extended out of the park, through a residential area, and south of Lemon Ave not the Fullerton College campus. A new line was established at Lemon and Berkeley to keep people from filtering back up into the park.”

Eventually, the “People’s Park” was cleared of “dirtbag hippies.”

Another confrontation between the youth and the police occurred at CSUF in the Spring of 1970, when an appearance by Governor Ronald Reagan sparked a series of student protests that drew thousands, lasted for weeks, and involved the occupation of campus buildings.

“During this same period of unrest throughout the nation, many agencies began to form and train special riot control squads,” O’Brien writes. “Fullerton was among the first, if not the first in Orange County to form what was called the Special Enforcement Detail (SED)—it was a forerunner to SWAT.”

O’Brien was on the original SED squad sent in to quell the CSUF protests.

“When we arrived on campus there was a crowd of about 2,000 people,” O’Brien writes. “During the exchange that took place after we moved into the crowd, several officers were injured, but none seriously. A number of students and other participants were also injured.”

Click HERE to read more about the 1970 student protests at CSUF.

As a member of the SED squad, O’Brien was also called in to quell such countercultural events as a hippie festival at Disneyland (including the legendary “Pot Day on Tom Sawyer’s Island”), and the massive 1970 Laguna Rock Festival.

The 1970s

The Department established a “community relations bureau” in 1971, which eventually included the D.A.R.E program instructors, School Resource Officers (SROs), and the Neighborhood Watch program.

In 1974, the department was expanded with a $1.4 million building.

Chief Bornhoft encountered some controversy when he ordered the investigation of an alleged bribery attempt from a housing developer and a City Councilmember, which prompted the council member to try to get the chief fired.

“I have no apologies to make to anyone,” Bornhoft said of the investigation. “That’s the way government should function. There should be checks and balances. I don’t believe that just because an official is an elected official and he is possibly involved in a criminal offense, I can walk away from it and let someone else do it. I feel it is my responsibility to investigate it.”

According to a 1977 LA Times article, Bornhoft’s reign “has been marked by controversy. A sizable segment of the community has supported Bornhoft, seeing him as a conservative, iron-willed, law-and-order chief. His supporters contend that the streets have been safe and the crime rate has held at a modest level. Others however contend that Bornhoft was not sensitive to the problems of minorities and unable or unwilling to communicate with the people.”

Bornhoft retired in 1977, and was replaced by Martin Hairebedian, a 23-year veteran of the LAPD.

By the 1970s, the Fullerton Police Officers Association was becoming a more powerful union which negotiated with the city for higher pay, benefits, and working conditions.

“In 1979 the association fought for and won a 30% single year increase,” according to the FPOA history. “The members not only walked the picket line in front of city hall but they also rallied the business community.”

The 1980s

In 1983 the FPBA changed the name to the current Fullerton Police Officers Association.

When Martin Hairabedian retired in 1987, Philip Goehring became chief of police. He had worked for the department since 1961. He got a law degree in the 1970s and taught police science courses at Fullerton College.

“The department had a bad reputation in the community,” Goehring said upon taking over the department. There had been 75 citizen complaints registered against officers the year he arrived.

While he was chief, Goehring created the first written policy manual and oversaw automation of police records.

The 1990s

In 1990, tragedy struck the Fullerton Police Department when undercover officer Tommy De La Rosa was killed in Downey in a drug bust gone bad.

Thousands attended De La Rosa’s funeral and years later a street was named in his honor.

During the 1992 LA riots, some FPD officers were sent to assist the LAPD and the National Guard. Ironically, the LA Riots began because an all-white jury acquitted the LAPD officers who were caught on tape brutally beating Rodney King.

In 1991, Chief Goering became engulfed in controversy when it was revealed that he had written a letter to the District Attorney on behalf of his friend’s son, who had been convicted on a drug charge.

“With the memory of Tommy de La Rosa, a popular Fullerton narcotics detective murdered in an ambush this past summer in Downey still fresh in their minds, Goering’s rank and file officers were outraged when the letters became known,” the Fullerton News-Tribune reported.

Despite an official apology, Goering’s officers had begun to lose faith in him, and he retired in 1992.

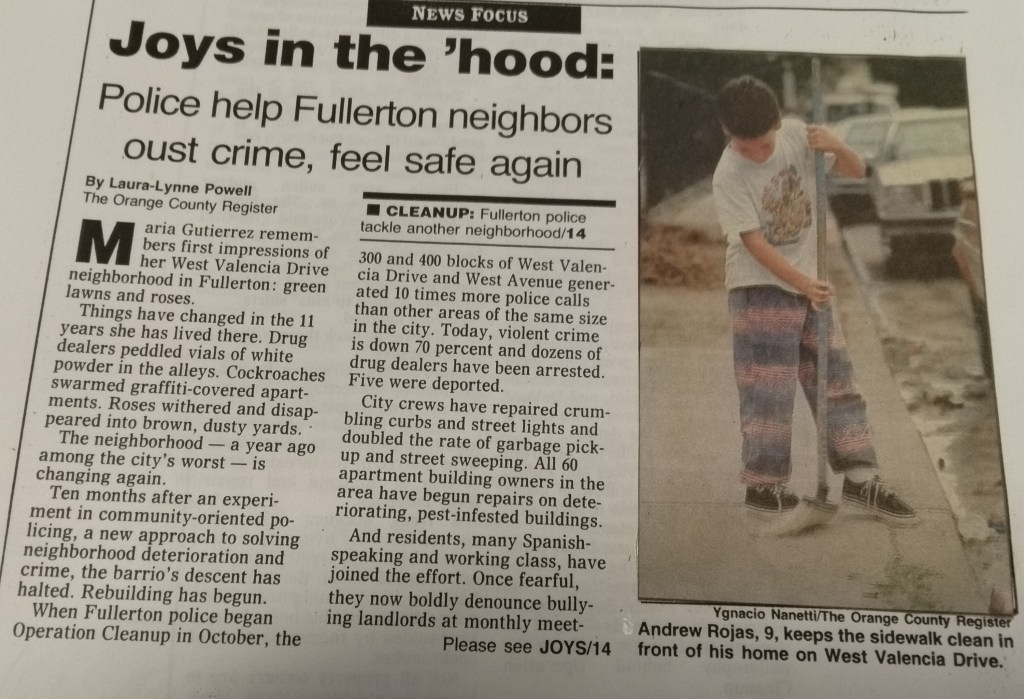

In the early 1990s, the Fullerton Police Department created a program called “Operation Clean-Up” which was (initially) focused on improving quality of life in a few Latino-heavy neighborhoods in south Fullerton that were experiencing the impact of local gangs.

Initially, the program involved sending officers on mountain bikes into the neighborhoods to attempt to build a better rapport with the community. This was an attempt at “community policing.”

Lieutenant Tom Bashan told the Fullerton News-Tribune, “When I first started [police work], it was ‘we against them.’ That attitude is gone. You get to know who the people are, you know most things about them, you start developing other ways of handling people besides strict enforcement.”

The program seemed off to a good start, even winning a Governor’s Award.

In 1993, Pat McKinley, a 29-year veteran of the Los Angeles police Department, was chosen to become Fullerton’s next Chief of Police.

McKinley had been involved in the formation of the LAPD’s SWAT squad, which was the first in the nation. It was created following the 1965 Watts Riots and was an important step in militarizing the police, and ramping up aggressive policing tactics.

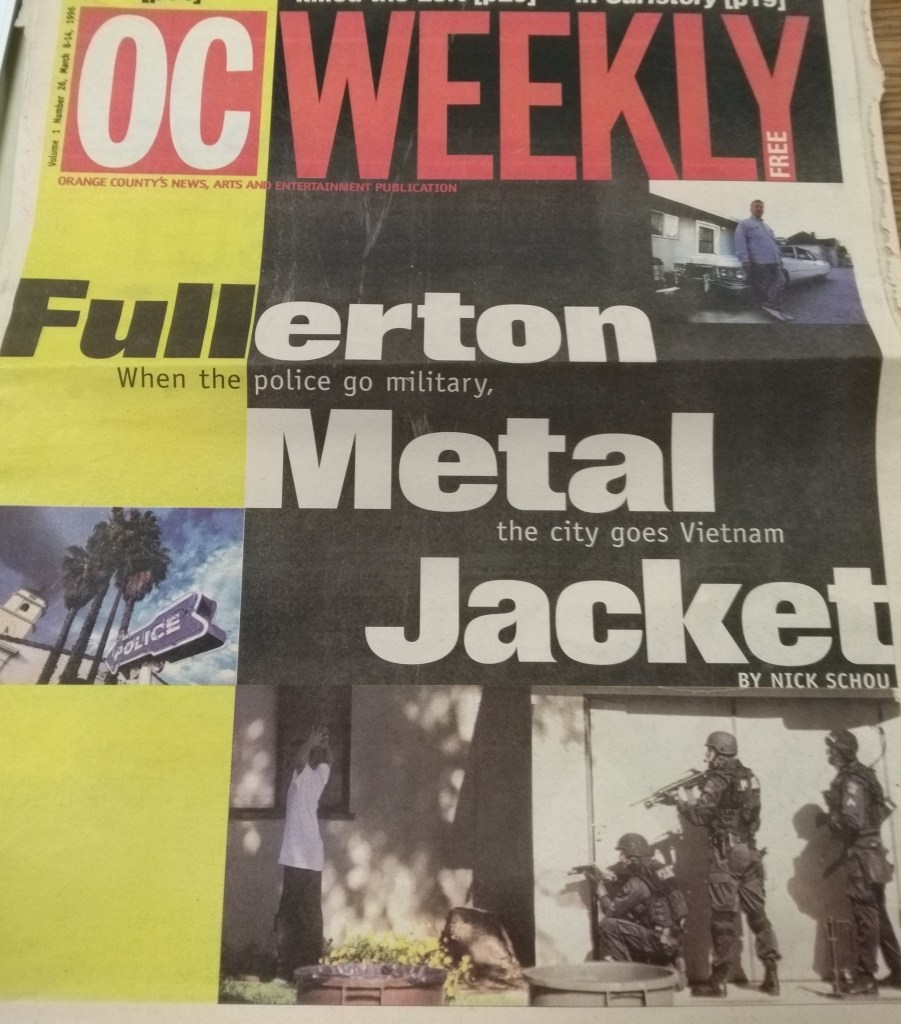

It was under the leadership of Pat McKinley that the community policing activity of “Operation Cleanup” took a much more aggressive turn.

The Fullerton Police department conducted an aggressive “sweep” of over 33 homes in the Maple area of South Fullerton, breaking down doors of suspected “drug dealers” and terrorizing families.

Reporting for the OC Weekly, Nick Schou wrote that the department “adopted operations reminiscent of Vietnam: an occupying army bent on separating the ‘bad guys’ from the ‘responsible’ population it claims to protect—and, at the same time, using brutal tactics that tend to punish both groups in equal measure.”

Following the sweep, McKinley faced a room full of angry residents at a meeting at the Senior Center.

An elderly Mr. Alberto Sambrano said, “I have lived here since 1939 and I have never seen anything like this before, the way they treated my 70-year-old wife. They destroyed my garage, a dresser in the house and a tool shed. We were treated like animals. They handcuffed my grandson Jonathan Navarro, who has never been in trouble. They took a gun my dad had given me 50 years ago.”

“Officer #1037 pulled my disabled brother up from his hospital bed and threw him on his wheel chair,” Gloria Hernandez told the chief.

Maple area resident Bobby Melendez said, “Use of stormtrooper tactics by the police and physically & verbally abusing people in their homes is not a minor matter.”

Charges of excessive force also occurred when heavy-handed police tactics were used against mostly Latino students from Fullerton College and local high schools during a protest.

“More than 20 students suffered slight injuries when Fullerton police, assisted by officers from several neighboring cities, used pepper spray and arrested six people, ending a rally and march of about 300 students who were demanding more Latino educators and more Chicano studies in schools,” the LA Times reported.

Apparently the protest, which had started at Fullerton College, turned into a March through Fullerton streets, and ended with a clash with police near Lemon street.

“One of the girls in front of me was hit with a baton and it hit me on the side,” Grace Ruiz, a 15-year-old high school student said. “The police didn’t need to hit us with their batons or spray us with pepper spray.”

In 1994, the Fullerton Police Officer’s Association (the police union) started a Political Action Committee to funnel money to City Council Candidates they felt would support their interests, and occasionally oppose candidates they did not want. This PAC remains an important source of campaign contributions.

The 2000s

In 2000, the FPOA-PAC endorsed Chris Norby and Mike Cleseri for City Council. They were rewarded with a new contract that brought about the “3% at 50 retirement package” and a significant pay increase. In 2000, the FPD got a new a new high-tech crime lab.

In 2002, the FPOA-PAC supported Don Bankhead, Leland Wilson, and Shawn Nelson for City Council. They all were elected.

In the early 2000s, a new subculture caught the attention of the FPD–rave culture.

“Hours after 250 undercover narcotics officers finished an intense Rave Parties seminar at Fullerton City Hall last Friday, local police found signs of the Hollywood club culture at a local nightclub and high school dance,” the Fullerton News-Tribune reported.

“This is one scary culture,” said Fullerton Police Sgt. Joe Klein, president of the Region V chapter of the California Narcotics Officers Association, sponsors of the two-day workshops.

Apparently, Fullerton club In Cahoots came under fire for hosting rave nights.

Following 9/11, the North Orange County Regional SWAT team was organized.

In 2004, the Fullerton Police Department got a $12 million renovation.

Chief McKinley retired in 2008, and was replaced in 2009 by Michael F. Sellers.

“I have always told my officers that we have three jobs,” Sellers said. “Our first step is to save lives. When lives are not at stake, our next job is to protect life. When that’s not an issue, our job is to help improve the quality of life for our citizens, and that is done through community-oriented policing.”

At the time of his hiring, Sellers taught classes in ethics, leadership and community-oriented policing at Fullerton College.

The 2010s

In 2011, Sellers’ ethics and leadership were put to the test when six Fullerton police officers were caught on video brutally beating a homeless man named Kelly Thomas to death.

Local residents began to flood City Council chambers and organize weekly protests outside the police department, demanding accountability for the killing of Thomas.

What did Sellers do? He went on disability leave one month after Thomas’ death, and then retired.

Capt. Kevin Hamilton was selected to serve as acting chief, and then he retired.

Two officers, Jay Cicinelli and Joe Wolfe, faced criminal charges over the death of Thomas, and the department faced three internal investigations by a special consultant. Both Cicinelli and Wolfe were ultimately acquitted, sparking one of the largest protests in Fullerton history.

Also, as a result of their perceived lack of leadership after the death of Thomas, three City Council members, including former Chief Pat McKinley, were recalled by the voters.

Dan Hughes, a 28-year veteran of the department, was appointed Police Chief in 2013.

Although the Kelly Thomas case was the highest profile incident of police brutality in the 2010s, there were others, such as the cases of Veth Mam and Edward Miguel Quinonez, both off whom were attacked by officer Kenton Hampton, who was also involved (but not indicted) in the Kelly Thomas case.

Officer Albert Rincon was accused of sexually assaulting several women in the back of his cruiser. And in 2012, corporal Vincent Mater was found guilty of destroying evidence after a man committed suicide in his cell at the Fullerton Police Department.

Dan Hughes retired early in 2016 after allegations that he gave special treatment to former City Manager Joe Felz, who drunkenly crashed his car into a tree after an election-night party and then attempted to flee the scene.

Hughes was hired as VP of security at Disneyland. The District Attorney filed a felony charge against former police Sergeant Rodger Jeffrey Corbett for falsifying a police report about the Felz incident.

Hughes’ replacement as chief was David Hendricks who (not long after being hired) got into hot water after drunkenly assaulting an EMT outside a concert in Irvine in 2018. He was charged and pled guilty.

Hendricks was released and replaced by Robert Dunn.

The 2020s

In 2020, Fullerton Police Officer Jonathan Ferrell shot and killed resident Hector Hernandez. This sparked years of protest by Hernandez’s family and community members. Although the DA declined to file charges against Ferrell, the city paid out an $8.6 million settlement to Hernandez’s family. This indicates a pattern in which officers who kill people in the line of duty rarely face criminal consequences, but sometimes (if there is enough public outcry) the city (aka the taxpayers) will pay out millions to the family of the deceased.

Also in 2020, following the death of George Floyd, there were large-scale protests and rallies for justice and police reform, including here in Fullerton.

In 2021, the Fullerton Police Department collaborated with other local agencies to create Project HOPE, with the purpose of doing more proactive outreach to the local homeless community. This program still exists today.

Because of a general lack of an adequate social safety net for the homeless, the job often falls to the police to deal with a social problem that they are ill-equipped to deal with. Sometimes the police collaborate with social service agencies (as with Project HOPE), and other times the police are asked to be strict enforcers–clearing homeless camps, arresting the homeless, and sometimes (as in the cases of Kelly Thomas and Jose Luis Naranjo Cortez, brutalizing them).

In 2023, Chief Dunn left the department and Capitan Jon Radus became Fullerton Police Chief.

That same year, the Police Department started using a drone to monitor Downtown Fullerton and other areas.

In 2024, Fullerton police killed Alejandro Campos Rios outside a McDonalds. This prompted more protests.

This year (2025), Fullerton Police killed a young man named Pedro Garcia. Another homeless man, Jose Luis Naranjo Cortez, died in Lemon Park after an encounter with the police.

Although it may seem like there have been more police killings since 2020, this is more likely the result of recent California state laws that require mandatory public reporting of in-custody deaths. It is likely that, in previous decades, many in-custody deaths were not made known to the public.

The Fullerton Police Department does a fair amount of community outreach/public relations events like the annual National Night Out.

The local police union, the Fullerton Police Officers Association remains active in local politics, using their Political Action Committee to support and/or oppose candidates, often successfully. This has allowed the police budget to remain much more stable than other city employees who have had to weather much steeper cuts.