The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

As part of my research into Fullerton history, I’ve just finished reading an excellent book called Fullerton: The Boom Years by Sylvia Palmer Mudrick, Debora Richey, and Cathy Thomas. The book vividly chronicles Fullerton’s extraordinary growth after World War II, as orange groves gave way to housing subdivisions, shopping centers, schools, and industry.

I present here a book report on some interesting things I learned.

Like much of Southern California, Fullerton experienced rapid growth and development after World War II. The population grew from 10,442 in 1940 to 85,987 in 1970.

Housing

Housing restrictions and shortages created by the Great Depression and the War led to a massive pent-up demand. And after the War, the floodgates opened.

Thanks to the GI Bill, returning servicemen were able to purchase affordable homes and pursue nearly free higher education. Housing developers couldn’t keep up with demand, but they sure tried. Development after development replaced orange and lemon groves.

“By August 1955, twenty-seven homes were being added to the city’s residential neighborhoods each weekday,” the authors write. “In 1955 alone, the city approved fifty-five new tracts for a total of 3,910 lots.”

Many of Fullerton’s older housing subdivisions (those built in the 1920s and 1930s) had racially restrictive covenants that barred nonwhites from occupying or owning property. This is what created segregated neighborhoods—with Mexicans and African-Americans unable to buy or rent homes outside carefully proscribed neighborhoods.

But in 1943, Fullerton resident Alex Bernal successfully challenged these racial housing covenants. When he and his wife bought a small home at 200 East Ash Avenue with a restrictive covenant, fifty white neighbors signed a petition asking Bernals to move. When that didn’t work, they filed an injunction against the Bernals.

The case went to trial, and the Bernals won, with Judge Albert R. Ross ruling that the Bernals could stay in their home. Doss et al v. Bernal was one of the earliest legal victories against racial housing covenants in the nation.

Although this type of housing discrimination became nationally illegal in 1948, it didn’t totally end, as is chronicled in the book A Different Shade or Orange: Voices of Orange County, California Black Pioneers.

Education

With the housing and population boom came the need for new schools to accommodate the children of the “Baby boom.”

“From January 1951 to January 1961 alone, three hundred new elementary school classrooms were added as the student population rose from 1,969 to 11,626,” the authors write. “From 1949 to 1966, the Fullerton Elementary School District constructed almost one school per year.”

Between 1945 and 1970 the Elementary School District grew from four to twenty-one schools.

The only remaining pre-war schools in Fullerton are Maple School, Fullerton Union High School, and Fullerton College. Every other school in Fullerton that exists today was build after World War II. And each of these older schools was significantly expanded after the war.

CSUF opened in 1959 on over 200 acres of former orange groves in east Fullerton, and eventually expanded into the massive campus it is today—one of the largest in the CSU system.

The GI Bill and the Master Plan for Higher Education in California made college nearly tuition free during the 1960s and 70s.

The end of World War II brought the Cold War, as tensions mounted between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The fear of communism led to “Red Scare” policies like school teachers and administrators having to sign loyalty oaths and schoolchildren doing “Duck and Cover” drills, as if getting under a desk would save someone from a nuclear blast.

The local newspaper ran a five-part series on “Survival under Atomic Attack.” Bomb shelters were built, and thousands of pounds of survival supplies were hidden in the tunnels under Fullerton High School.

Protest and Change

Although Fullerton was a pretty conservative place, the Civil Rights and Anti-War movements of the 1960s and 70s still had an impact here, mostly on the campuses of Fullerton College and CSUF, and at Hillcrest Park.

In the late 60s and early 70s, students would often gather at the Hillcrest Park “bowl” on Sundays “to protest the war, make speeches, and play rock music,” often to the chagrin of the residents who lived near the park.

In May 1969, following residents’ complaints, police moved in to clear the park of “approximately 300 rock and bottle-throwing students,” the authors write. “A total of twenty-two arrests were made, and two officers were injured. In a later incident, rioting crowds armed with rocks and bottles attacked officers attempting to close the park…As a result of that incident, the city council, at the urging or Chief Bornhoft and Parks and Recreation Director Jim Cowie, voted to close Hillcrest Park on Sundays.”

Following this, the local chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) organized a protest at Amerige Park and city hall.

“Protests—led by a group of Fullerton College students that called itself the Hillcrest Liberation Front—continued at various spots around the city through the remainder of 1969 and into 1970. After several months, the council temporarily lifted the ban, and on April 25, 1971, a rock concert attended by an estimated 2,500 people was held in the Hillcrest Park bowl. Eleven arrests were made for primarily drug-related offenses, but officers deemed the event mostly peaceful.”

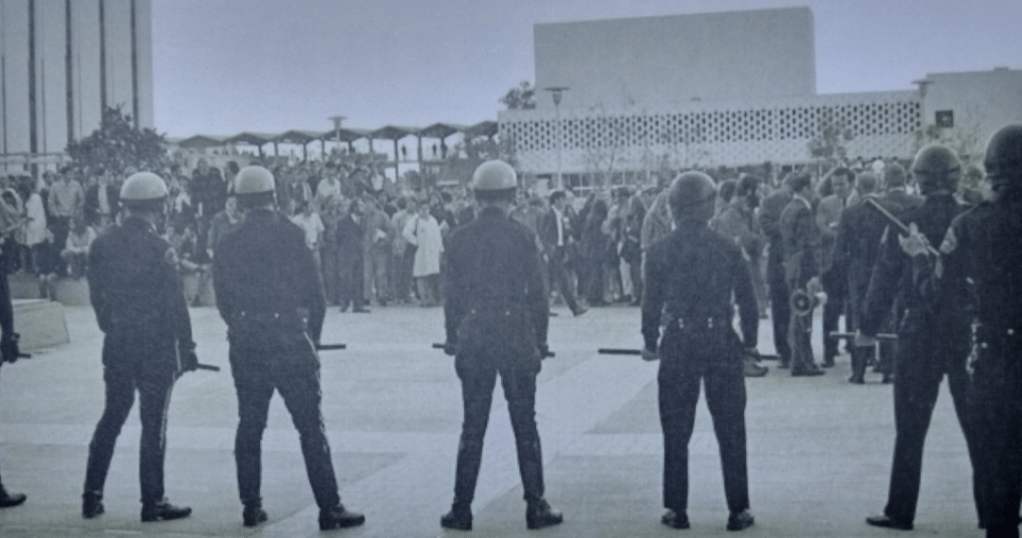

A visit from conservative governor Ronald Reagan to CSUF in 1970 sparked months of protests and even the occupation of at least one building on campus.

“The usually quiet commuter campus became the site of mass unrest and violent events that continued throughout the spring semester in, with protesters occupying the administrative wing of the Letters and Science Building,” the authors write.

In 1972, antiwar activist Ron Kovic led local students on a protest march to the corporate offices of Honeywell Inc, a defense contractor.

That same year, the local school board voted to close Maple school because it was determined to be a segregated school. Read more about that story HERE.

Business and Industry

Although the postwar years saw the gradual decline of the once-sprawling orange groves, the citrus industry still remained through the 1960s, and workers were still needed for the harvests. The Bracero Program brought thousands of Mexican workers north to work the fields of California.

As had happened a few times throughout its history, white residents opposed the construction of housing for the Mexican workers in Fullerton. In the early 1950s, a proposed citrus labor camp in southeast Fullerton led to a recall campaign against the council members who supported it. Although the recall ultimately failed, it highlighted lingering and widespread prejudice against Mexicans.

Some of the larger industrial businesses that built plants in Fullerton in the postwar years included: Beckman Instruments, Kimberly-Clark, Sylvania Electrical Products, and Hughes Aircraft.

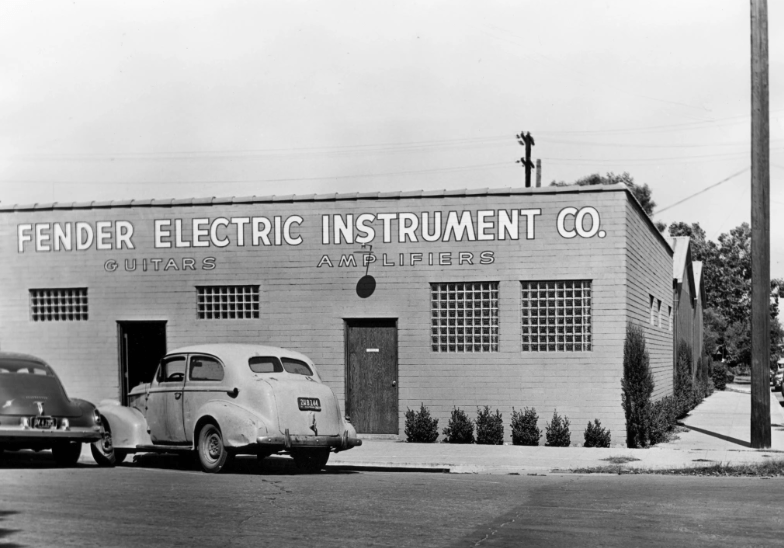

Some businesses that existed before the war (like Kohlenberger Engineering, Pacific Hawaiian Products, Hunt Foods and Industries, and Fender Musical Instruments) saw major expansion of their facilities.

But industry had a dark side, too.

“While the air and space industry and other manufacturing industries were a driving force in the extraordinary postwar economic expansion of Fullerton, these companies left the city with a legacy of pollution, including the contamination of groundwater with toxic chemicals, heavy metals and persistent carcinogens, as well as soil degradation,” the authors write.

One of the more egregious polluters in Fullerton was Raybestos-Manhattan Inc., which at one time was the second-largest manufacturer of asbestos-containing products in the US.

Another source of pollution was the McColl dump site, a 22-acre site next to what is now Ralph Clark Park, which was used for disposal of refinery waste during and after World War II. In 1982, after residents complained of odors and health problems, the EPA placed McColl on its superfund list, and some remediation steps eventually taken (it was “capped”).

On the retail front, the postwar years saw the introduction of more “big box” department stores like Montgomery Ward, JCPenney, and Sears, which tended to have a negative impact on the smaller “mom and pop” stores downtown.

In 1958, the Orangefair Shopping Center opened at the southeast corner of Harbor Boulevard and Orangethorpe.

Postwar prosperity also saw an increase in leisure-oriented businesses like Carter Bowl, Merilark Roller Rink, Cinderella Dance Studio, the Checkered Flag Mini-Raceway, and golf courses.

Local cocktail lounges included the Melody Inn, Happy Chaps Bar, 2J’s, and The Mill.

Politics and Government

For much of Fullerton’s history, its elected city council members were conservative white males. In fact, every city council member from 1904 (when the city was incorporated) to 1970 was a white male. Click HERE for a full list.

But the civil rights and women’s movements brought an increased push for diversity. The first female council member and mayor was Frances Wood (elected in 1970). The first person of color on the city council was Louis Velasquez (elected in 1976).

Arts and Culture

The Boom Years gives mini-profiles of a number of notable people who came to prominence in the arts after World War II. Here are some of them. Click their names to read more.

Ruby Berkeley Goodwin (author).

Ethel Jacobsen (poet).

Philip K. Dick (science fiction writer).

Betty Lou Nichols (ceramic artist).

Lewis Sorensen (dollmaker).

Florence Millner Arnold (artist).

The Hunt Branch Library, a gift of Norton Simon’s Hunt Foods and Industries Foundation, opened in 1962. It was designed by renowned architect William L. Pereira.

“Perhaps one of the city’s greatest missed opportunities occurred in 1964, when the Hunt Foods and Industries Foundation, a project of millionaire industrialist and philanthropist Norton Simon, announced that it was willing to donate $500,000 to the city for construction of a museum to house Simon’s renowned art collection,” the authors write. “however, negotiations with the city fell through.” Simon took his collection to Pasadena, opening the Norton Simon museum there in 1972.

Fullerton’s contributions to post-war popular music include Fender Guitars, the Rhythm Room (a popular spot for Chicano rock bands), and (a bit later) significant early punk bands like Social Distortion and the Adolescents.

Interestingly, the punks of the late 1970s and early 1980s were often rebelling against the clean-cut suburban landscapes their parents had created and enjoyed.

Other Notable Events

1949: Local pilots Bill Harris and Dick Riedel set a world endurance flight record in their airplane Sunkist Lady.

1950: A fire destroyed a large portion of the 100 block of West Commonwealth, including the McCoy and Mills car lot.

1957: St. Jude Hospital opened.

1963: A new City Hall opened.

1973: A new Public Library opened.

You can purchase a copy of Fullerton: The Boom Years HERE.