The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

California State University, Fullerton played a very significant role in my early adulthood. I got my B.A. in English there in 2004, and then went on to get a M.A. in English in 2007. That same year, I began my college teaching career. I taught English composition at CSUF for about ten years as an adjunct faculty. Being adjunct, I also taught at other local colleges, including Fullerton College and (briefly) Santa Ana College.

As a student, and then as faculty, I had mixed feelings about CSUF. There were things about it that I loved. I (mostly) had great professors. I enjoyed the Arboretum, the outdoor concerts. I loved the Library (until it started getting rid of its book collections in favor of computers). But there were things that kind of bugged me too—the steadily rising tuition, the low pay of adjunct faculty in comparison to full-timers, the construction of things like a multi-million dollar fitness center while student fees were increasing, the multi-year closing of the Library in the 2010s, etc. I left CSUF around 2017 to pursue a stint in local journalism.

Around 2008, retired history professor Lawrence de Graaf published a surprisingly in-depth history entitled The Fullerton Way: 50 Years of Memories at California State University, Fullerton. De Graaf had taught at CSUF almost from the beginning and his insights are extremely valuable.

As part of my larger research and writing about Fullerton history, I present here summary of De Graaf’s book.

The genesis of what would become CSUF was the passage of Assembly bill 4 in 1957, establishing a four-year state college in Orange County.

The chosen site in east Fullerton was (like much of Orange County) orange groves. The state began acquiring the land in 1959.

“Thus began the transformation of acres of oranges into one of the largest institutions of higher education in the nation,” de Graaf writes.

Fullerton, and Orange County in general, was experiencing a period of rapid growth following World War II, as orange groves gave way to housing subdivisions, schools, shopping centers, and industrial parks. The passage of the GI Bill created a large number of potential college students.

In 1959, William B. Langsdorf was named the first president of what was initially called Orange County State College.

As the state acquired land, the Fullerton High School District allowed the new administrators to use the second floor of an old (condemned) building on the Fullerton High School campus.

The first college “campus” was a building at the newly-built Sunny Hills High School, on the other side of town. It was here, in 1959, that the college offered its first classes. Later that year, faculty and administrative offices moved to an old farmhouse (the Mahr house) on the site of what would become CSUF.

In 1960, as it continued to acquire more land and funding for permanent buildings, the college built temporary buildings and bought four wooden barracks from nearby March Air Force Base.

In 1960, the state adopted the Master Plan for Higher Education in California, a very important document that established the roles of community colleges, state colleges (CSUs), and Universities (UCs). Perhaps the most significant aspect of the Master Plan was that it promised “tuition free” higher education in California. And for a couple decades, it (mostly) kept this promise. Those who attended CSUF in the 1960s and 1970s paid minimal student fees. This would unfortunately change starting in the 1980s, but more on that later.

“Funding increases reflect a period in which higher education remained a relatively high priority in state spending. The Cold War and the Space Race focused public attention on the need for teachers and well-trained students, and federal programs like the National Defense Education Act began to supplement state financing of higher education. During this period (early 1960s) the budget for all state colleges more than doubled,” de Graaf writes. “Through the 1960s, state colleges boasted that they offered ‘tuition-free’ education, not a fully true assertion. Each college charged a material and services fee of $33 per semester for full-time students; non-residents were charged $90. Students and faculty paid parking fees, and there were small fees for admission and registration.

In 1963, the first permanent classroom building was completed—the Letters and Science Building, which was later named McCarthy Hall, after early professor/administrator Miles McCarthy. This was followed by the Music, Speech, and Drama building, which opened in 1964.

The school nickname, the Titans, was chosen in 1959 by students.

In 1962, a strange event put the college on the map—the nation’s first intercollegiate elephant race, a goofy event dreamed up by students.

“On Friday, May 11, 12 elephants with malhouts (riders) and trainers, most of them in Indian garb, lined up as if the event was the culmination of months of careful planning. Cars lined up for miles along the few narrow roads serving the campus. By the time the race started, 10,000 spectators stood along Dumbo Downs and 89 reporters assured nationwide coverage,” de Graaf writes. “Most of the elephants never completed the course, some refusing to run at all. Harvard was declared the winner. Stories of the race appeared in Newsweek, Time, and Sports Illustrated.”

Following this, the elephant was adopted as the school mascot.

A need for student housing became apparent when the basketball coach brought several Black athletes from Detroit to play at the college.

“During the 1960s, most Orange county communities essentially excluded blacks, save for a substantial community in Santa Ana and smaller ones in Fullerton and Tustin, near the El Toro Marine base…Consequently, these students found it impossible to rent accommodations,” de Graaf writes. “Continued hostility from the local population posed a significant obstacle for black students. Housing remained virtually impossible to obtain. One early black student made 108 applications before the 109th gained him the right to lease an apartment. Three other black students found an Anaheim woman willing to rent to them, only to have a mob of white neighbors pressure her into canceling the deal. Most black students either used Orthrys Hall [an early dorm] or made long commutes from places outside Orange County. Police posed another problem, stopping black students to inquire what they were doing on campus or in North Orange County…One sign of community attitudes came in 1965 when the first campus pastor, Rev. Al Cohen and his wife adopted a racially mixed child. The community complained to campus officials about this arrangement, and after months of threatening phone calls, the Cohens gave up their child for re-adoption and subsequently left the campus.”

CSUF began in the context of the Cold War, and the politics of the time affected the college, “epitomized by declaring the science building a nuclear fallout shelter as well as by the suspicion that Communists or their sympathizers lurked within America’s government and schools. One of the most vocal proponents of this idea was the John Birch Society, and one of its biggest areas of influence included Orange County.”

During this time, all professors had to sign loyalty oaths, and “President Langsdorf issued an order forbidding Communist speakers on campus. This act roused occasional debate and some editorials in the Daily Titan,” de Graaf explains.

In the 1960s, Orange county was still an overwhelmingly white area, and Latinos were not yet attending college in large numbers. In 1967, the college had only five black students and similarly small numbers of Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos.

In 1967, a battle for academic freedom was waged in Fullerton, following a graduate student production of Michael McClure’s controversial play “The Beard” at CSUF.

“Staging a play notorious for graphic language and a simulated sex act in conservative Orange County was daring particularly following court cases against its production in 1966. Given unauthorized tickets to the private performance, reporters from local newspapers sparked a maelstrom of media scrutiny. The ensuring legal battle between the CSF academic community and a group of conservative state senators resulted in a Senate investigation and hearing. The incident became a cause celebre for academic freedom,” De Graaf writes. “Senator John G. Schmitz, a John Birch Society member, warned budget cuts to higher education could emerge as one means to handle ‘flagrant moral corruption and revolutionary violence planned and carried out behind the cloak of academic freedom.’”

To read more about The Beard episode, check out my report HERE.

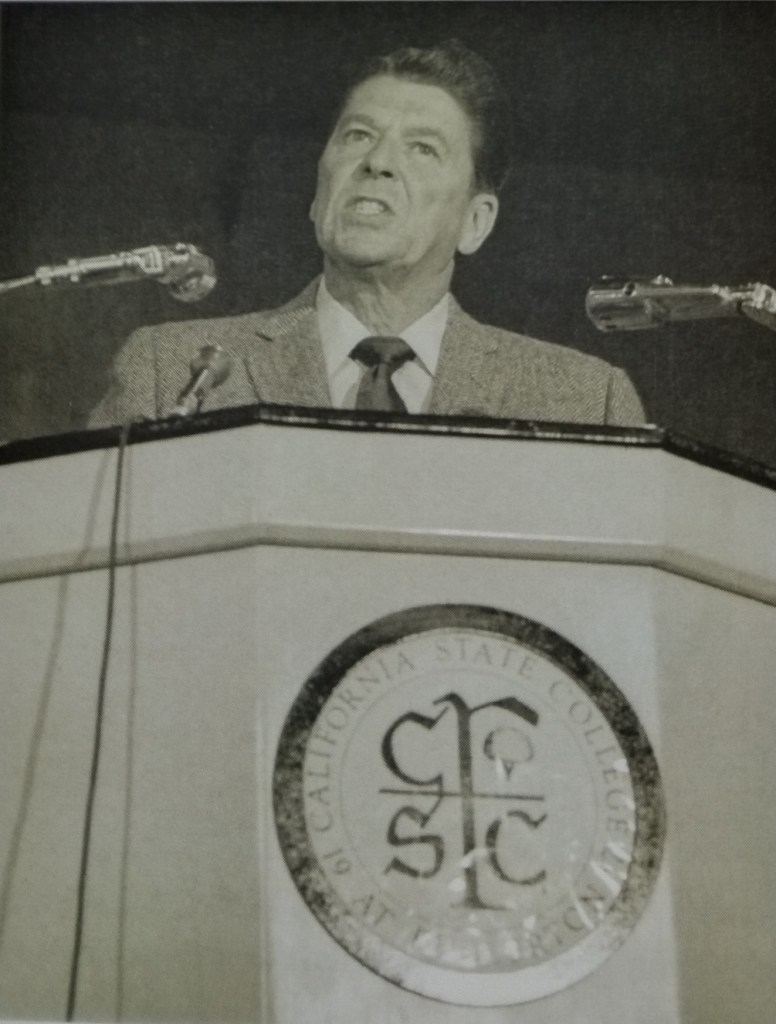

Ronald Reagan was elected governor in 1966 and immediately ordered budget cuts for universities.

“To accommodate new students, the campus set up 18 trailers. Since this building crisis coincided with Governor Reagan’s repeated efforts to cut state expenditures, many at CSF deemed him responsible for such makeshift quarters. Consequently, the temporary offices were dubbed ‘Ronald Reagan Hall,’” de Graaf writes.

It was the Reagan administration who proposed increasing student fees.

“Ironically, the invitation to Governor Ronald Reagan to give his first address as governor at a public campus in California served as the catalyst for the turmoil of spring 1970,” de Graaf writes.

Reagan gave a speech in the campus gym, during which some students heckled him. College officials brought disciplinary action against two of the hecklers, Bruce Church and Dave MacKowiak, and the police filed criminal charges against them.

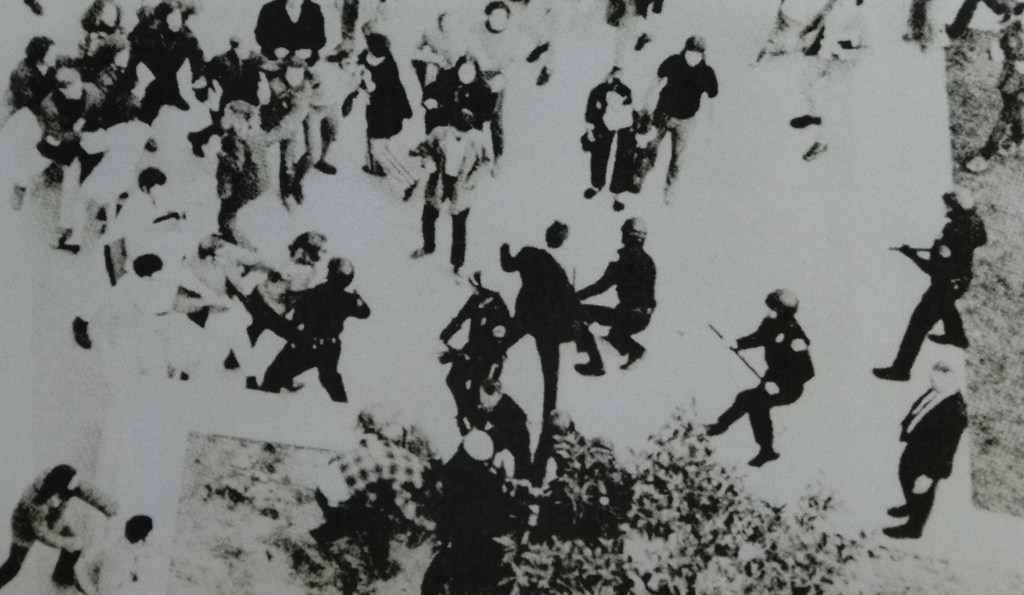

Students held a rally in the quad to “Free Dave and Bruce” demanding that the school and the police drop charges against the students. When Langsdorf refused, hundreds of students staged a sit-in in the Letters and Science building and Langsdorf’s outer office. These students were forcibly removed by police in riot gear.

When the Student Faculty Judicial Board tried to hold disciplinary hearings on Bruce and Dave, students broke in and disrupted the proceedings. Vice President Shields called Fullerton for police assistance.

Around 90 officers responded: “Police began arresting those who stayed in the quad and charged into groups with clubs. In a few minutes, some faculty managed to get between students and police. Professor Hans Leder declared the whole Quad an impromptu class, soon after which Shields convinced the police to leave. The number of students arrested for heckling or the events on March 3 grew to 37. Daily meetings on the quad and displays of banners continued through March and into April,” de Graaf writes.

The protests were given added intensity by the Kent State massacre, as well as the war in Vietnam. Students occupied the Performing Arts Building.

This sparked a reaction by local conservatives, who organized a group called Save Our Society (SOS), which was supported by Fullerton State Assemlyman John Briggs. After an SOS meeting on campus in May, someone burned one of the temporary buildings next to the one used by student protesters.

As the summer began, the protests died down, with some students arrested and given jail time or campus discipline.

For a more comprehensive account of the 1970 student protests, check out my report HERE.

Conservative groups also sometimes protested on campus, such as in 1972, when professor Angela Davis was invited to speak at CSUF, and in 1977, when Vietnamese anti-Communists “demonstrated against the showing of a Cuban documentary, assaulting the professor showing the film.”

The many campus groups and clubs highlighted the diverse background and political ideas of students—ranging from the Jesus Movement to the Black Student Union to MEChA to a Gay Student Union.

By the end of the 1970s, women comprised 52 percent of students. During that decade, a Women’s Center and a Women’s Studies Program were created.

William Langsdorf resigned in October 1970, and Dr. Donald Shields became the new president.

CSUF officially became a university in 1972.

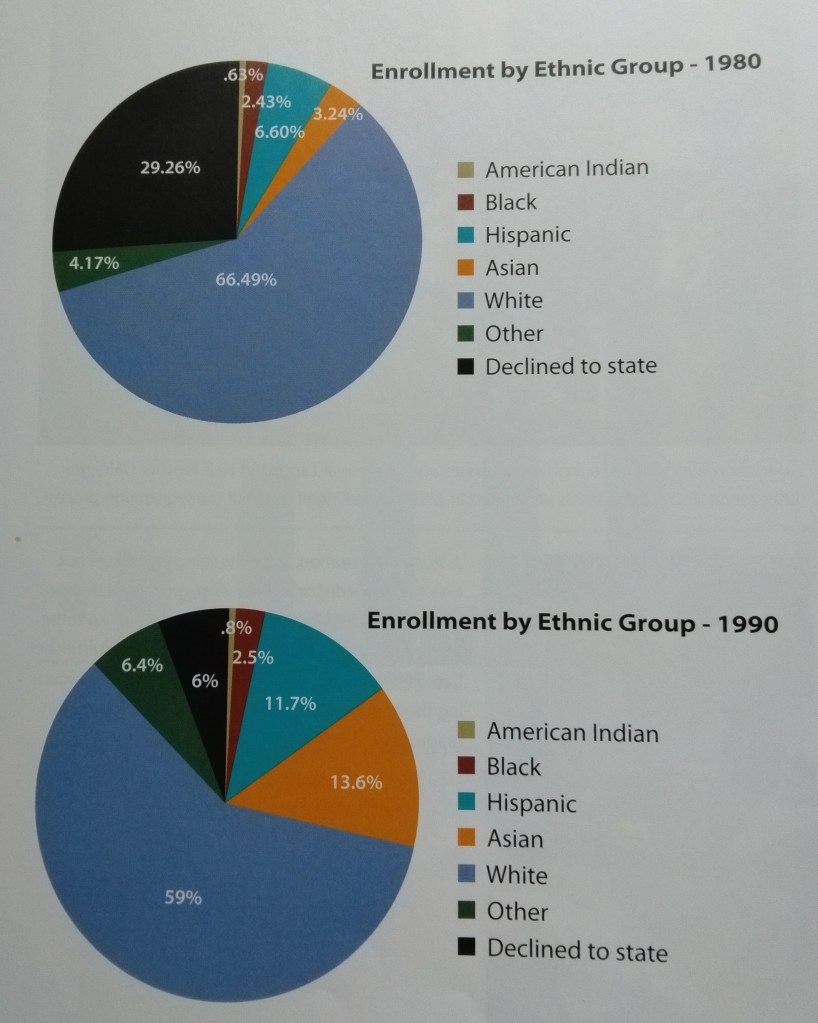

In 1978, the CSUs set up systemwide Student Affirmative Action Program to encourage minority enrollment.

“The state budget for higher education tightened steadily through the early 1970s,” de Graaf writes. “State funds were further constricted in the wake of Proposition 13, which reduced the education budget.”

Two major cost-saving measures were increasing student fees, and hiring more part-time faculty (who were paid less than full-timers, and received few benefits).

Faculty unions were established at the end of the 1970s.

In 1976, a mass shooting occurred at Cal State Fullerton. It was “one of the worst massacres at an American university until the shooting at Virginia Tech in 2007.”

The shooter was Edward Charles Allaway, a mentally disturbed custodian who, on the morning of July 12, 1976, entered the basement of the Library armed with a .22-caliber rifle and he killed six people: Paul Herzberg, Bruce Jacobsen, Seth Fessenden, Frank Teplansky, Debbie Paulsen, and Douglas Karges. He then walked to the first floor, where he shot and wounded Maynard Hoffman. Library assistant Stephen Becker and Librarian Donald Keran tried to wrestle the gun from Allaway, but he fatally shot Becker and wounded Keran before leaving the library and driving away.

“The whole rampage lasted five minutes, leaving seven people dead and two wounded,” de Graaf writes. “Later that day, Allaway phoned police to report his location and gave himself up.”

Allaway was tried, found guilty of murder, and sentenced to life in prison. He escaped the death penalty because some on the jury found him insane. Later he was moved to Patton Mental Hospital in San Bernardino.

Tragically, “Two more people soon lost their lives as an indirect result of Allaway’s shooting,” de Graaf writes. “Shortly after the trial, his sister, Shirley Sabo, fatally shot herself in guilt and sorrow over the tragedy. Earlier, on April 1, 1977, Richard Drapkin, another staff member who had worked with several of the victims, jumped from the Humanities Building to his death.”

In 1978 CSUF planted seven trees on campus (for each of the victims), establishing a Memorial Grove.

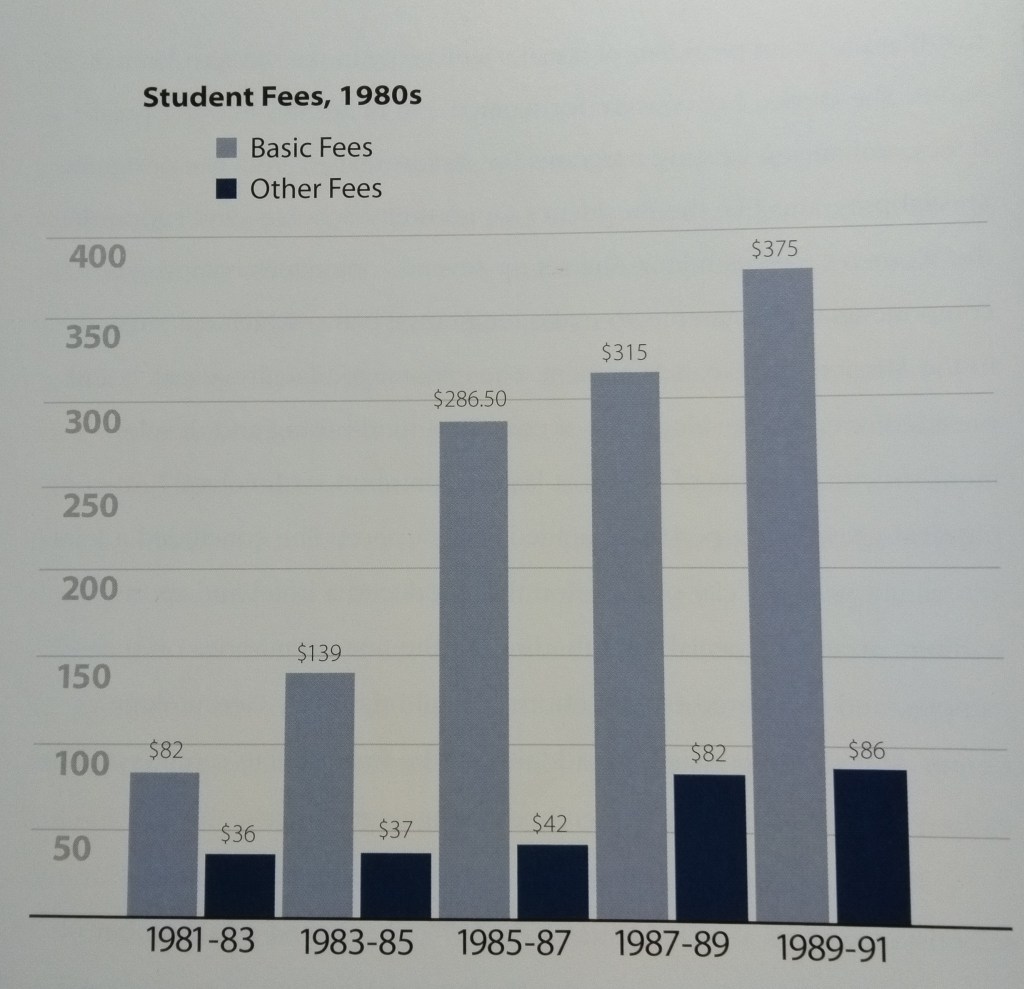

Student fees were steadily growing. By 1980, a full-time student paid $250 per semester in fees, not to mention the cost of housing, which nearly doubled in the 1970s. To offset this, federal financial aid in the form of Pell Grants, the Middle Income Assistance Act (1978), and Federal student loans were expanded.

Mens baseball and women’s gymnastics won national championships in the late 70s. Football was less successful: “Black players walked off the team in 1974, charging Coach Yoder and Stoner with discrimination.”

As a result of local fundraising, student activism, and community support, the Fullerton Arboretum broke ground on campus in 1977, and opened in 1979.

Facing a budget deficit, “Governor Jerry Brown issued an executive order to ‘unallot’ two percent of the budget for the CSU and UC, and Chancellor Dumke ordered a freeze on CSU purchases, hiring, and promotions.” This was followed by another round of student fee hikes.

In 1981, Jewel Plummer Cobb was chosen as president of CSUF, the first African American woman to become president of a university on the west coast.

“Along with her scientific research and teaching, Cobb was a pioneer in opening racial and gender opportunities. She helped further physical growth in a period of limited state support,” de Graaf writes. “It surprised many that a county with a reputation as one of the most conservative in the state made such a bold choice of president.”

Facing budget shortfalls, CSUF sought creative ways to finance new construction. In 1983, the university entered into an agreement the city of Fullerton redevelopment agency and to finance a sports stadium for the football team, with extra income from allowing a hotel to be built on campus.

A student group organized to oppose the project, criticizing “the university’s partnership with a privately owned corporation, the impact of such a large private facility so close to the college, and the use of Redevelopment Agency funds for a corporate venture.”

The hotel opened in 1989, and the sports stadium opened in 1992. Ironically, that same year CSUF cancelled its football program.

In the early 1980s, CSUF made agreements with local cable companies to provide local public access television.

Unfortunately, in 1986 it was revealed that for nearly two years, staff had allowed Tom Metzger, “an advocate of white supremacy and a former Ku Klux Klan member, to produce a program “Race and Reason” that advocated racial separatism and included anti-Semitic content,” de Graaf writes.

This prompted protests from the Anti-Defamation League and students from the Coalition Against Apartheid and Other Human Rights Violations, who demanded that the university shut this program down. President Cobb said that the principle of free speech protected Metzger’s program, but then one of the cable companies ended its agreement with the university, ending the program.

The Titan Channel continued broadcasting other programs through the rest of the 1980s.

In 1986-87 funds from the state lottery began to be allocated to the CSU, partly offsetting periods of budget cuts.

In 1990, Milton A. Gordon became President of CSUF.

Gordon “would devote a great deal of energy to establishing relations with local corporations and increasing the success of CSUF in raising funds from private parties to offset years of cuts in state funding,” de Graaf writes.

“In the early 1990s, the Board of Trustees adopted a goal of each campus raising at least 10 percent of its state general fund appropriation from private sources,” de Graaf writes. “This practice grew to the point that the university was essentially selling rooms and in some cases seats at fixed prices to any contributor able to pay that amount to get his or her name on it.”

The early 1990s brought another recession with the decline of the aerospace industry, with local Hughes Aircraft closing in 1994.

As had by now become a pattern, the state offset budget woes by increasing student fees, as if the recession somehow did not affect students or their families.

State university fees were $390 a semester by 1990, and rose to $792 by 1994.

Meanwhile, a university study exploded the four-year degree myth, finding that “Of freshmen who entered CSUF in 1995-97, fewer than 10 percent completed a B.A./B.S. in four years…This completion rate was a sobering indication of how an institution at which over three fourths of the students held outside jobs different from traditional ideals,” de Graaf writes.

By 1999, CSUFs 839 part time faculty (who were paid significantly less) outnumbered full-timers.

“Concerns involved the growing gap in compensation and working conditions between the two groups and demands for faculty to assess their teaching effectiveness and incorporate new technologies into instruction,” de Graaf writes. “Could people paid only for instruction time be expected to keep pace?”

Office space was often shared between several part-timers in a single room.

“The years 2000-2008 were ones in which the economy of California fluctuated between boom and crisis, while revealing structural weaknesses that defied political repair,” de Graaf writes. “Governor [Gray] Davis cut the CSS budget by $131 million, but then allocated a portion of that to cover enrollment growth. From 2002 to 2005, the CSU saw its budget reduced by $522 million.”

In the early 2000s, the state budget gave $3 billion to state universities and $9.9 billion to state prisons.

By 2003, student fees had risen to $786 a semester for full-time undergraduate students.

“In the ensuing two years, they went up to $1,260 with parking and Associated Student fees on top of that,” de Graaf writes. “By 2006, undergraduates were paying $2,520 a year, graduates $3,102. These fee hikes provided nearly half of the total funding for the CSU during the early-mid 2000s.”

CSUF had come long way from the “tuition-free” higher education promised in 1961.

The university continued to rely on private donations from corporations and wealthy individuals, and then named buildings after these donors, such as the Steven G. Mihaylo (owner of Crexendo Business Solutions) Business Building, Dan Black (nutritional supplement businessman) Hall, and the Joseph A.W. Clayes III (real estate/avocado investor) Performing Arts Center.

“By the mid-2000s, the College of Business an Economics was the largest such college accredited in California, the third largest in the United States,” de Graaf writes.

By 2004, CSUF employed over 1,000 part-time faculty, compared to 366 full-time faculty.

A bright spot in all of this was the Titan baseball team, who went to the college world series in 2001 and 2003, and won in 2004.

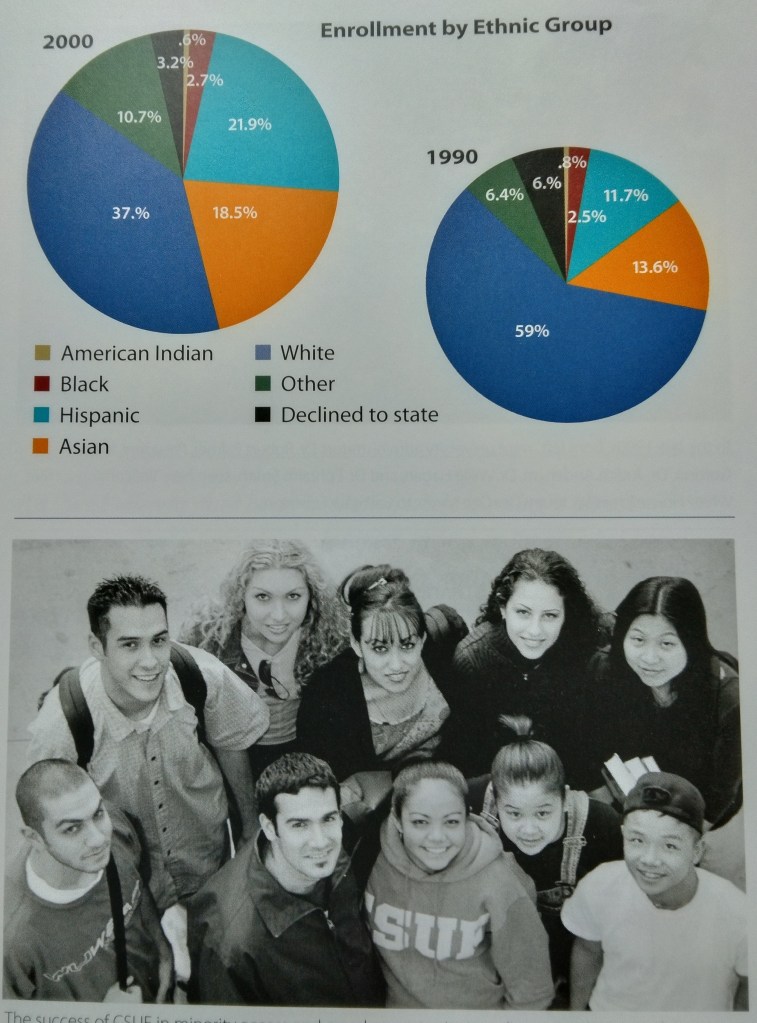

By 2008, CSUF had more than 37,000 students: “This growing enrollment reflected the increasing ethnic diversity of the region, with over half of the students at Cal State Fullerton being persons of color by 2008.”

De Graaf’s history ends in 2008, and I will end with a few closing quotes from the author:

“It is only when one steps back to the earliest years of Cal State Fullerton to look over its 50 years that the full extent of these changes is realized. The most obvious changes were the sheer growth of the campus: from orange groves with three residences to a densely built cluster of about 25 mostly multi-story buildings; from 452 students to 37,000; from a graduating class of five to one of nearly 10,000; from one degree and major to more than 100.”

“Much of this growth occurred for the same reason that the college was mandated in 1957–Orange County itself continued growing throughout this period. The transformation from orange groves to suburban sprawl had already underway for a decade before Orange County State Collge came on the scene, so in physical growth as well as population, CSUF essentially reflected ongoing trends.”

“Cal State Fullerton was more of a catalyst in some of the most dramatic and less predictable changes in the campus and county. One was in the demography. Into the 1960s, Orange County was overwhelmingly white in population and notorious for its hostility to blacks and indifference to other minorities. That people of color would constitute over have of CSUF’s enrollment and that two of its four formally appointed presidents would be African-American represent a remarkable shift in social attitudes as well as population trends. By having a positive attitude toward ethnic diversity from its beginnings and an array of programs to promote groups historically underrepresented in higher education to come to its campus, Cal State Fullerton played a significant role in the amazing ethnic transformation of Orange County.”

As of 2025, CSUF’s annual tuition is $7,470 for in-state students and $20,070 for out-of-state students.