The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Fullerton’s population grew from 2,690 in 1910 to 4,415 in 1920.

Fire Protection

In 1908 following a big fire downtown, Fullerton created its first volunteer fire department. In 1914, voters approved bonds for a fire truck and named officers. J.M. Clever was chosen as chief.

Health

A new hospital was approved in 1912 at the corner of Pomona and Amerige. This building still stands today, although it is no longer used as a hospital.

In 1918, a deadly flu epidemic spread across the world, including the United States. Though it likely did not actually originate in Spain, it became known as the Spanish Flu. Hospitals were filled to capacity, and lots of people died, including here in Fullerton.

International Affairs

South of the border, the Mexican Revolution caused thousands of immigrants to migrate north, to the United States.

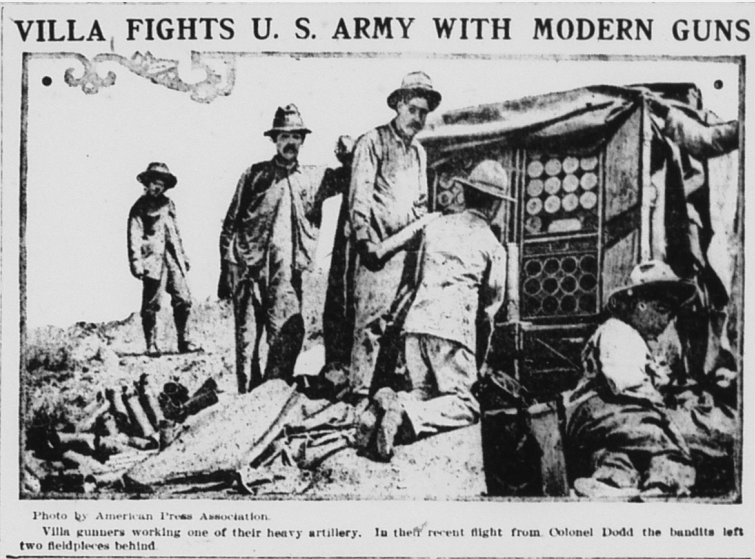

In 1916, Pancho Villa’s fighting forces raiding American settlements along the border, prompted a full-scale invasion of Mexico by U.S. troops, much to the consternation of Mexican president Carranza, who was also fighting Villa.

One unfortunate consequence of the conflict with Mexican revolutionaries was that it led to fear and suspicion of Mexicans in the United States, who were sometimes viewed as being in sympathy with Villa, or even secretly helping his cause.

“That secret recruiting of Mexicans for the Mexican army has been going on in Fullerton for the last week became known today. Half a score of Mexicans are known to have left town and others are said to be preparing to leave,” the Tribune reported. “Further precautions against possible rioting of lawless Mexicans here took concrete form Thursday night when the board of trustees, at a special meeting, approved the addition of thirty-five citizens to the ranks of the police force as deputy marshals…Five deputy marshals have been on the force for some time, swelling the total of officers available to forty, and other additions are to be made within a short time.”

In 1914, World War I began in Europe. The United States would not officially enter the war until 1917. Upon this announcement, local residents formed a Home Guard, and the high school formed a military company.

The U.S. government instituted a draft to obtain soldiers for the American military. Eligible adults aged 21-30 had to register. 385 people registered in Fullerton. Charles C. Chapman was local draft board chairman.

The Tribune actively sought to shame those “slackers” who did not register for the draft, printing the names of those required to register, and those who were caught not registering.

Patriotism was in the air, manifesting in rallies, Red Cross drives, Liberty Bond drives, and a massive fourth of July celebration.

Two local young men, Fred Strauss and Nels Nelson, registered for the draft. According to an oral history interview with Strauss conducted decades later, he explained what prompted him to enlist.

“We went there to Los Angeles and had a lot of beer. Finally, after we had had enough beer and we got to feeling pretty good, I said to my pal, ‘Let’s go and enlist and join the Army.’ And he said, ‘Okay, we’ll go.” So they enlisted.

Amidst all the patriotic fever, one local group took a public stand against the war–the local Socialist Party.

High School principal E.W. Hauck enlisted, or was drafted.

Unnaturalized Germans over the age of 14 living in the United States had to register with the postmaster.

In 1918, Germany surrendered, essentially ending the war.

The 1916 Flood

A terrible flood took place in 1916 when the Santa Ana river overflowed its banks. This was particularly devastating for Mexican-American families who lived in the lowlands along the river’s path.

The Tribune stated, “Ten Mexican families are being cared for by Alfred Vail, who lives between Fullerton and Anaheim, and other Mexicans, are being cared for at Anaheim.”

“The body of Mrs. Eleareintia Nunez, a Mexican woman 89 years of age, was found by C.A. Myers in his walnut orchard. The body was identifited by Jose Nunez as that his mother, Mrs. Elcarcintia Nunez. Nunez also identified the body of the 12 year old Mexican boy discovered Thursday as that of his son Juan,” the Tribune reported. “The body of one of Nunez’s sons is still missing. Alberto, aged 9, was in the house at Peralta that was washed away by the flood last Sunday night. There were three persons in the house, the two boys and their grandmother. Nunez and his two daughters had gone to Anaheim for supplies, and did not return Sunday on account of the rain. That is all that prevented them from being in the house that went down the river.”

After the flood, local leaders began to talk about plans to control the waters of the Santa Ana river.

In 1913, Fullerton built a new municipal water system with a pumping plant, a reservoir, and 12 miles of underground water pipes.

Additionally, the city was building a modern sewer system.

City Council Members

Below are the City Council Members elected in each election during this period:

1914: George Anin, R.S. Gregory, August Hiltscher, and E. Livingstone.

1916: J.R. Carhart, J.M. Clever, A.H. Sitton, and Perry C. Woodward.

1918: R.R. Davis, Robert Strain, and Perry Woodward.

1920: W.F. Coulter, L.P. Drake, and R.A. Mardsen.

Women’s Suffrage

The state of California was ahead of the curve when it came to women’s suffrage. Women in the Golden State got the right to vote in 1911, as a result of a ballot measure (Prop 4), fully nine years before the passage of the 19th Amendment. Women could also run for political office.

Of course, not everyone was in favor of granting women the right to vote, as this advertisement in the Tribune demonstrates:

In the leadup to the vote, there were large gatherings on the issue of women’s suffrage, including in Fullerton. Ultimately, Prop 4 passed, and women were allowed to vote in California.

In 1920 the first woman was elected to public office in Fullerton. Belle J. Benchley was elected a grammar school trustee. Benchley would eventually move to San Diego, where she would become a noted zookeeper and author.

1920 was also the first year women were allowed to serve as trial jurors in Orange County.

Prohibition

In just about every election cycle since Fullerton incorporated in 1904, petitioners put the liquor question on the ballot. In 1912, with the large number of women registered to vote, the town voted (once again) to ban liquor licenses, thus making Fullerton a “dry” town.

The national prohibition question was also playing out locally.

“Laying plans for the 1917-18 campaign, prohibition workers from all parts of the county gathered in Fullerton Monday,” the Tribune reported.

The US Senate had passed the 18th Amendment in 1917, but it would not be ratified by a majority of the states until 1919, and national prohibition did not take effect until 1920, with the passage of the Volstead Act. Prior to that the Wartime Prohibition Act took effect in 1919, which banned the sale of beverages having an alcohol content of greater than 1.28%.

Both locally and nationally, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union had been an active proponent of Prohibition for many years.

Education

In 1910, Fullerton’s second high school, which was located at Amerige Park, burned down. In 1911, Fullerton voters approved a bond measure to fund the construction of a new high school. There was some debate over the location. Ultimately, the site was chosen on Chapman Ave. where Fullerton High School is today.

In 1913, Fullerton College was established. Today, Fullerton College is recognized as the oldest continuously operating community college in California.

The new college campus started on the newly-built high school campus on Chapman Avenue.

In 1914, the principal of FUHS was Delbert Brunton, and teachers were chosen by the Board of Trustees.

A popular movement seeking to prevent both racial and labor strife was called “Americanization” in which employers provided education to “Americanize” its foreign-born immigrant workforce. In contrast to today’s appreciation for diversity and cultural and linguistic difference, the Americanization movement sought to mold different ethnic identities into English-speaking Americans.

“Where no English is spoken disease breeds, because the immigrant cannot read the suggestions of the Board of Health. The I.W.W. [Industrial Workers of the World] breeds where no English is spoken,” the Tribune reported. “The country is awake to the danger of the alien population, and ‘Americanizing’ must become the great national movement.”

Locally, citrus growers, in collaboration with educational leaders, established special schools in “Americanization” for their predominantly Mexican workforce.

Read more about Fullerton’s Americanization program HERE.

Racism

In 1913, the California legislature passed the California Alien Land Law (also known as the Webb–Haney Act), which prohibited “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning agricultural land or possessing long-term leases over it, but permitted leases lasting up to three years. It affected the Chinese, Indian, Japanese, and Korean immigrant farmers in California. Implicitly, the law was primarily directed at the Japanese.

It passed 35–2 in the State Senate and 72–3 in the State Assembly.

The law was the culmination of years of anti-Asian sentiment in California, going back to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

By 1920, anti-Japanese feeling in California was intense. Apparently, it was politically advantageous to demonize Japanese immigrants. A Senator James D. Phelan came to Fullerton to speak on the “Japanese Menace.”

California was not the only state to pass an exclusionary law against the Japanese. Texas (of course) followed suit, a long with Arkansas, Florida, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Speaking of racism, in 1914, California had laws on the books which outlawed interracial marriage. The News-Tribune printed an article which pointed out that some Japanese people in California had married white Americans. Given the widespread anti-Japanese sentiment at the time, this article was likely meant to provoke outrage, rather than sympathy. Interracial marriage, which was outlawed since California became a state in 1850, would remain illegal in California until the 1948 court case Perez v. Sharp.

In the early 20th century, there was an emerging pseudo-science called eugenics which was the basis for racist beliefs and practices, such as laws which prevented interracial marriage.

While Fullerton was building new housing and businesses for its white residents, in 1919, there was vocal opposition for the construction of housing for Mexican Americans.

“The first thunderbolt was in the form of a petition from 117 prominent citizens headed by former trustee August Hiltscher and backed up by William French, former city marshal and now justice of the peace and newly appointed city recorder. This petition was a protest to the building of a concrete structure by the Santa Fe at Highland and Santa Fe avenues for the housing of its Mexican employees,” the Tribune reported. “The petitioners asked if it would not be possible to prevent the erection at that point or at least the housing of the Mexican element in that locality. The matter was discussed from every angle but there seemed to be no relief from a legal standpoint, and finally a resolution was adopted by the board asking the company to abandon that site and erect its building near its section houses, and City Attorney Allen was delegated to present the resolution in person to Superintendent Hitchcock at San Bernardino. Mr. Allen left for San Bernardino this morning to carry out the mission.”

“City Trustees Davis, Strain, and Woodward and City Attorney Allen were closeted with Superintendent Hitchcock of Hitchcock of the Santa Fe in his private car in the yards of the company at this place this morning to discuss the matter of the housing of Mexican workers at Highland and Santa Fe avenues by the company,” the Tribune reported. “A mass meeting has been called for this evening at the city hall for taking action.”

Ultimately, the Santa Fe Railroad won, and got the housing built, much to the consternation of Fullerton residents, many of whom showed up at a “mass meeting” to protest the construction.

“The Santa Fe Railroad Company will continue its work and complete its building at the corner of Highland and Santa Fe avenues for the housing of its Mexican employees and will house them right there,” the Tribune reported. “This bald assertion is made because the mass meeting at the city hall Thursday evening to take steps to avert the menace simply went up in smoke, and went sky high. The council chambers was filled to the doors with property owners, principally from the “infected” district, and they talked and talked and talked, but never got anywhere.”

One of the protestants was heard to say, “Well, we don’t like it, but we’ve got to take it.”

Crime

In 1912, after an Anaheim marshal was shot and killed by a Mexican man, local law enforcement scoured the region searching for the killer. There was even talk of lynching.

An ordinance was passed with the aim of “separating the bad element among the Mexicans from their guns.” Civil liberties were perhaps not being equally respected.

“It is my desire that all my deputies should enforce this ordinance at every instance, and especially among the Mexicans. It will be your privilege and duty to search every man you suspect of carrying a concealed weapon, and if found to bring him to the county jail, at the expense of the county,” OC sheriff Charles Ruddock stated.

In other crime news, a rancher named Gerorge Biggs brutally slayed his neighbor F.A. Montee and his wife in a debate over a strip of roadway. As far as I can tell, there was not a similar effort made by law enforcement “to separate the bad element among the whites from their guns.”

Fearing juvenile delinquency, in 1916 the board of trustees of the Fullerton Union High School District urged the City Trustees to pass an ordinance banning teenage boys from pool halls.

Also, in true Footloose fashion, local churches successfully lobbied to have a planned series of outdoor dance events banned.

The biggest crime story of 1920 was the murder of local rancher Roy Trapp and the assault of his wife by a Black man named Mose Gibson, who fled town after the crime.

There was a manhunt for the murderer, who had given the false name of Henry Washington.

Because the murderer was Black, many local citizens wanted to lynch him when he was caught. This was the 1920s, when lynchings were not uncommon.

Eventually, Mose Gibson was captured near the Mexican border, and brought to the Los Angeles jail, where he confessed to the murder.

Gibson was tried and sentenced to death by hanging.

As reported by the News-Tribune, feeling in Fullerton regarding Gibson was “intense.”

Editor Edgar Johnson didn’t exactly help matters by calling Gibson “the lowest type of human beast.”

Prior to being hanged, Gibson also confessed to several other murders and crimes across the United States. One of the people he confessed to murdering was J.R. Revis of Louisiana. Unfortunately, a Black man named Brown, it turned out, had been wrongfully lynched for the murder.

While Gibson was in San Quentin prison awaiting execution, a group called the Housewives Union sent a letter to the governor of California, pleading for the man’s life.

“We ask your attention to the case of Mose Gibson, condemned to suffer the death penalty, September 24,” the letter stated. “The fact that the man is a negro is likely of itself to prevent him fro having that consideration before the law which a white man in his humble position might receive. It seems that when a negro is the culprit, that the white man feels it his peculiar privilege to indulge in any amount of brutality.“

Alas, Gibson was hanged, nonetheless.

Labor

In labor news, members of the Industrial Workers of the World (or “Wobblies”) passed through Fullerton sometimes, spreading their message of working class solidarity. They were viewed with suspicion, fear, and hostility.

“Cowed by the guns of the police, sixteen I.W.W.’s were captured here Thursday night after repeatedly defying the crew of a Santa Fe train who attempted to drive them from the cars,” the News-Tribune reported in 1917. “Ten of the I.W.W.’s were marched to the depot, where they were held under armed guard till Sheriff Jackson and deputies arrived from Santa Ana. Six more I.W.W.’s were captured later and they were driven from town.”

And a bit later: “Shortly before 8 o’clock Thursday night word was received from Los Angeles at the Santa Fe depot in Fullerton that I.W.W.’s had taken possession of an east bound freight train that was due here a few minutes after 8. Deputy Sheriff Murillo was quickly called and he immediately sent word to Marshal French. The latter responded at once and a few minutes later the two were joined by Deputy Marshal Woodford.”

In response to a strike by Mexican Citrus workers, growers brought in “Negro” labor from Los Angeles.

“Negroes are being imported in to Orange County in relieve the labor situation developing through the refusal of Mexicans to take contract jobs or to work for less than $3 or $4 a day,” the Tribune reported. “Twenty-five were brought into the beet fields Tuesday afternoon from Los Angeles and agents of the sugar factories and farmers, are now in Los Angeles securing more.”

As a kind of punishment to the striking Mexican workers, some local merchants stopped allowing Mexican strikers to purchase food on credit.

With some wartime labor shortages, there were special provisions to bring in Mexican farm labor, but not Chinese Labor, which Californians were not keen on.

“Last year Mexicans were brought here to help in the sugar beet harvest. This was done through a resolution of congress allowing the immigration department to make that kind of an importation, and in the regulations those bringing in the Mexicans were under bond to return them to the border,” the Tribune reported. “This does not apply to Chinese labor. It is my firm opinion that efforts to get the bars lowered so that Chinese can come in will not be successful. Whatever the qualifications of the Chinese as a laborer may be, I don’t believe there is any possibility of getting congress to alow the Chinese to be brought in even temporarily.”

Oil!

Large oil companies like Standard Oil and Union Oil were buying up properties of smaller local companies in the Fullerton Oil fields.

“At the opening of the year 1916 the daily production of all wells in the field totaled 35,273 barrels,” the Tribune reported. “The production has been steadily increasing during the year until the daily production in round numbers is 55,000 barrels. The production for the past year will run close to 18,000,000 barrels.”

In 1914, a number of lawsuits were filed against A. Otis Birch, owner of the Birch Oil Company by landowners who felt they were cheated out of oil profits on their land.

In 1918, the pioneering Bastanchury family sued the Murphy Oil company for defrauding them of millions of oil dollars.

Back in 1903, Simon J. Murphy secured a lease of a couple thousand acres to search for oil. He told Domingo Bastanchury that he found no oil, and yet still convinced the old man to sell him the land for $35 an acre. He paid Bastanchury $79,000 for the land.

About a month after purchasing the land, the newly-formed Murphy Oil Company sunk a well that was a 3,000-barrel a day gusher. Many other oil-producing wells were subsequently sunk on the land.

In 1912, the Murphy Oil Company sold its oil holdings to the Standard Oil Company for around $24,000,000.

Meanwhile, Domingo Bastanchury died, and his lands fell to his widow and sons.

In 1917, former workers of Murphy Oil told Domingo’s son Gaston that they had actually discovered oil prior to the purchase of the land, and Murphy lied to Domingo about this fact.

The Bastanchury heirs sued Murphy for recovery of funds from the millions of barrels of oil that had been extracted over the past fourteen years, alleging that the property was obtained by fraud.

In 1919 the Bastanchury family won a large $1,200,000 judgment against the Murphy Oil company.

Meanwhile, local oil workers organized a union, also seeking better wages.

Perhaps a part of the widespread labor unrest, some oil wells were bombed in the Fullerton fields.

“Believing that they have in custody one of the perpetrators of the recent bomb outrages in the Fullerton oil fields the police today detained a man describing himself as Antone-Kratchel, aged 35, an Austrian, who was arrested at First and Gless streets by Patrolmen H.R. Boehm and J.Y. Walton,” the Tribune reported.

Culture & Entertainment

Before the Fox was built in 1925, Fullertonians went to see movies at the Rialto Theater. It was located at 219 N. Spadra (Harbor Blvd).

The Rialto Theater featured a talented musician named Winifred Wilbur, who played multiple instruments that accompanied the films.

In 1918, popular entertainer Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle made a special appearence at The Rialto.

Sometimes famous people would speak at the high school auditorium, including Helen Keller and politician and failed presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan.

In a more racist vein, there was in the Tribune an advertisement for the Geo. Primrose All White Minstrel Show, presumably featuring white people in black face.

The local American Legion post sponsored a Big Minstrel Show, which presumably featured white performers in blackface.

Another form of popular entertainment at this time was the traveling Chautauqua show, which came through town.

In 1920, the local Masons built a huge new temple which is now the Springfield Banquet Center.

Transportation & Infrastructure

In 1914, Fullerton voters approved bonds for the fire department but voted down bonds for road improvement. What else is new?

In 1917, Fullerton finally got a Pacific Electric passenger train line to pass through the town. The Pacific Electric “red cars” would become, by the 1920s, the largest interurban rail system in the United States. The whole system would unfortunately be dismantled in the 1950s, as southern California became firmly entrenched as a “car culture.”

Homelessness

The local policy toward homelessness had, for years, been to jail people on vagrancy charges. However, in 1916, given the inadequacy of the local jail, town Marshal French decided to stop this practice.

“They can implore as much as they want,” he declared, “but I shall place no more prisoners in the city jail. In the first place the arrest of vagrants and tramps is not included in the duties of the city marshal. It is up to the constable to make those arrests and if the county wants the floating class handled, let him do it.

“I shall no longer make an attempt to control the undesirable class in Fullerton so long as they violate no city ordinances. The necessity for a new jail will probably be impressed upon the people by the time the floating class is allowed to remain unmolested for a short time.

In 1917, in the category of “the more things change, the more they stay the same,” local authorities shut down a homeless encampment near the train depot.

“Officers early Wednesday evening raided a hobo camp east of the depot and sent thirteen tramps out of town with instructions not to return. The raid was made by Marshal French and Deputy Sheriff Murillo,” the Tribune reported. “Reports reaching Marshal French said the tramps had established a camp near the wye made by the branching of the Santa Fe to Richfield. The spot is favorite site for a camp with bums, a permanent camp having been established there last year despite daily raids by the police.

“When the two officers arrived at the camp Wednesday night the thirteen occupants were stretched about a camp fire, some of them lying down and others engaged in cooking supper.”

“None offered resistance when the officers searched them for arms. All of them were without weapons and most of them had no money.

“According to their story to the police they were on their way to San Diego, where they expected to find work in the kelp beds.

“Most of the crowd were young men and all of them were shabbily dressed. The oldest man in the camp, bent and grizzled, gave his age as 62 and told the police he did not know where he was going.

“The camp raided Wednesday night is the first that has been established by hoboes this year, according to Marshal French.”

Housing

Fullerton’s population was growing, and there was a housing shortage, so there was much new construction. The 1920s would bring a big housing boom to Fullerton. The Board of Trade established a “housing fund” to finance construction of new housing.

“The Housing proposition is the most important problem which confronts the city today. We not only need good houses but we need business blocks, as people who desire to engage in business here are turned away every day,” the Tribune reported.

In 1919, realtors R.S. Gregory and George A. Ruddock announced the opening of a new subdivision on six acres of walnuts and Valencias on the 200 block of West Whiting, next to downtown. Another new subdivision was Jacaranda Pl., developed by Charlie Gantz. Many of these homes still stand today as well.

In addition to housing, new business blocks and buildings were added to downtown, such as the Gardiner Building, McKelvey & Volz Drug Store, the Sanitary Laundry Building, and more.

Unfortunately, part of this “progress” meant destroying old buildings, such as the Henderson Blacksmith shop, which was one of the oldest shops in town.

The Town of Orangethorpe

Before the town of Fulleton was founded in 1887, some early ranchers settled in an area south of the town-to-be, an unincorporated community called Orangthorpe. In 1920, city leaders attempted to annex part of Orangethorpe so as to extend the city’s “sewer farm” which is now the Fullerton airport. The ranchers who lived around this area organized to fight this Annexation.

The ranchers were successful in blocking this annexation, and they even voted to incorporate as the town of Orangethorpe to protect the land from future annexation attempts.

Deaths

In 1912, Joseph Goodman, co-owner of the Stern & Goodman general store, passed away.

That same year, Colonel Robert “Diamond Bob” Northam, passed away after being assaulted in his home. Northam was for years the agent of the Stearns Rancho company–which owned and sold thousands of acres of prime southern California real estate. He was a colorful and wealthy local figure.

Chapman Avenue was originally called Northam Avenue. In 1911, his wife Leotia sued him for divorce, stating that she was fed up with his drunkenness.

In 1911, the Tribune painted an interesting picture of Diamond Bob: “He is now 65 years of age and a millionaire manufacturer and is widely known as a princely spender, bon vivant and general good fellow…Colonel Northam is a pioneer, coming here in 1870, and today, in addition to the manufacturing business at 110 West Twelfth street Los Angeles, has large realty holdings, including the beautiful country place, Los Robles Viejos at Santa anita, one of the well known show places of the big county.”

He had married his wife 10 years prior when he was 55. She was just 20, an aspiring actress.

Mrs. Northam said, “No one could have treated me better than Bob in every way…dresses, jewels, a beautiful home–I had all that heart could desire. But his constant drinking drove me to distraction…He is his own worst enemy and was fast becoming mine.”

In 1914, Jose Antonio Yorba, a descendant of the pioneering Yorba family of Orange County, passed away.

That same year, Loma Vista Memorial Park, Fullerton’s first cemetery was established. It remains Fullerton’s only cemetery, and many early pioneers are buried there.

B.G. Balcom, pioneering Fullerton banker, also died in 1914. Balcom Avenue is named after him.

In 1915, Fullerton co-founder Edward R. Amerige, who had served on City Council and in the California State Assembly, passed away.

In 1917, Charles E. Ruddock, former Fullerton marshal and Orange County sheriff, died.

“Ruddock was born in Chemano county, New York making him almost 53 years of age at the time of his death,” the Tribune reported. “He and his family came to Fullerton from Wisconsin in 1897 and since have made their home here. Serving a trifle more than two years as a city marshal of Fullerton, Ruddock also served as county sheriff from 1910 to 1914.”

Goodbye, Old St. George Hotel

The Shay Hotel, originally called the St. George Hotel, was one of the first buildings in town at the corner of Spadra (Harbor) and Commonwealth. Sadly, in 1918, it was torn down.

“Bright and early this morning a large force of men started in to dismantle this old landmark of Fullerton,” the Tribune reported. “George Amerige, the proprietor, has sold the building to the Whiting Wrecking Company of Los Angeles for wrecking purposes and the work of razing the old structure has started. Big signs with white background and black lettering have been plastered all over the exterior of the building which read “Watch It Go.”