The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Government and Politics

At the turn of the century, Fullerton was not yet incorporated as a town, and therefore had no City Council. The governing body was the County Board of Supervisors.

In 1902, Dallison Smith Linebarger, a Democrat who owned a livery [horse] business in town was elected to represent District 3 on the Orange County Board of Supervisors. He defeated fellow Democrat B.F. Porter (a Fullerton rancher) in the primary, and Republican William “Billy” Hale (also a rancher) in the general election. He would be re-elected and serve until 1912.

That same year, town co-founder Edward R. Amerige, a Republican, was elected to the California State Assembly. He would serve two terms.

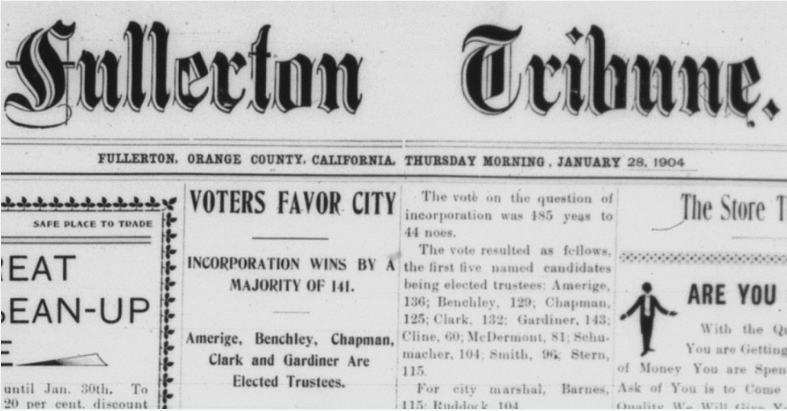

Fullerton incorporated in 1904. Residents voted to establish Fullerton as a city, complete with a Board of Trustees (City Council) and taxation powers. The first Board of Trustees was Edward Amerige, E.K. Benchley, Charles Chapman, George Clark, and John Gardiner.

W.A. Barnes was elected city marshal, George Ruddock was elected City Clerk, and J.E. Ford was elected city treasurer.

The newly-established Board of Trustees began to pass a series of ordinances. They established a fire protection district, a board of health, franchises with telephone, gas, and electric companies, built new sidewalks, and made street improvements.

They also passed ordinances prohibiting some things in town, most of which make sense–no fighting in the streets, etc. But some of the town prohibitions seem quite harsh, such as bans on vagrancy and cross-dressing.

There was some conflict over the appointment of a postmaster for Fullerton. This was a position appointed by local congressman Milton Daniels. Although a petition with 500 signatures advocated the appointment of Cora Vail, Congressman Daniels appointed Vivian Tresslar (a man), allegedly at the request of Mayor Chapman.

“Captain Daniels has announced that he will absolutely refuse to recommend the appointment of any woman for the position,” the Tribune stated.

Tresslar was also the hand-picked editor of the Tribune’s rival newspaper, the Fullerton News–which was bankrolled by Mayor Chapman.

During the 1906 election, eschewing any kind of journalistic objectivity, Tribune editor Edgar Johnson clearly had his favorite candidates. Prior to the election, he ran articles/editorials that advocated for what he called “The People’s Ticket,” which included City Trustee candidates E.R. Amerige, R.T. Davies, and L.P. Drake.

This was in contrast to what Johnson called “The One-Man Power Ticket.” That one man was Charles C. Chapman, whom Johnson had taken to calling the town “Czar” and “The Great I Am.”

Unfortunately for “the people,” the Chapman ticket swept the race. Chapman, for some reason, was not up for re-election–perhaps he had a four year seat.

Town co-founder Edward Amerige, who was a part of the “People’s Ticket” wrote a letter to the Tribune after the election condemning dirty political tactics of his opponents. His words show that not much has changed in over a hundred years:

“I desire to say a few words in your paper regarding the anonymous letter which was sent through the mails during the recent election. Such a contemptible, sneaking, lying and cowardly act is hardly worth replying to through the medium of newspapers. The proper place to answer such a blackmailing and malicious letter is through the criminal courts and should information be secured as to the authorship of this libelous letter such an action will be commenced. The men and parties who would stoop to such despicable means of trying to influence voters would stoop to anything to carry their ends, and are a dangerous and undesirable element in any community. Several of the parties who are mixed up in this disgraceful attempt to besmirch decent men are supposed to be respectable citizens, but when they resort to such methods and are so cowardly as not to dare sign what they write, they are worse than a coyote that roams in the dark.”

In 1908, the City Council election pitted the “All Citizens’ Ticket” against “The Peoples’ Ticket.” Tribune editor Johnson clearly favored “The Peoples’ Ticket, and they (mostly) won. The newly elected trustees (council members) were: Will Coulter, August Hiltscher, J.H. Clever, and William Crowther. The treasurer was W.R. Collis, the clerk was W.P. Scobie, and the Marshal was Charles Ruddock. Coulter was chosen as Chairman, or Mayor.

In 1910, the following men were elected to City Council: R.S. Gregory, E.R. Amerige, and George C. Welton. Roderick D. Stone was elected Marshal, C.A. Giles was elected City Clerk, and W.R. Collis was elected Treasurer.

At the state level, California was in the midst of quite a political shake-up, with the election of progressive Republican Hiram Johnson as governor in 1910. At this time, the California Republican Party was divided between the more establishment/conservatives (who were connected to large business interests like the powerful Southern Pacific Railroad) and the progressives, who wanted to enact many political reforms. One of these reforms was the creation of the direct primary system. This allowed the voters, rather than party bosses to choose candidates. It was intended to help “clean up” corrupt “party machine” politics.

Meanwhile, another town co-founder H. Gaylord Wilshire, a noted socialist, had his magazine the Challenge banned from the U.S. mail. He ended up changing the name of the magazine to Wilshire’s Magazine and shipping them out of Canada, to get around the ban.

News

Tribune editor Edgar Johnson spent considerable space ruthlessly attacking the competing newspaper in town, the Fullerton News, which was funded by mayor/orange grower Charles C. Chapman because he didn’t like the coverage he was getting in the Tribune. Johnson called the Fullerton News the Fullerton Snooze! When Chapman sought to end the city’s contract with the Tribune to publish official notices and give the contract to the News, Johnson again called him “Czar Chapman.”

Meanwhile, some of the front page “news” stories in the Fullerton News were blatant puff pieces about Mr. Chapman and his sprawling orange ranch. Below are a few excerpts:

“He comes of that sturdy American ancestry which has ever in past times of peril been the salvation, and must in like times to come, be the hope of this country.”

“Under Mr. Chapman’s ownership and management, this property has become the most famous orange ranch in the world, as well as one of the largest…Indeed, the Santa Ysabel is a model, perfect in every detail as an orange ranch and home, and one in seeking to describe it with justice would be forced to use language seemingly superlative to one who has not viewed it for himself. From the beautiful and elegantly appointed family residence to the cement flumes, ditches, and pipe lines no intelligent effort or expense has been spared, no opportunity neglected to bring everything as near perfection as lies within the power of human hand and mind.”

“It is to Mr. Chapman’s liberality that the Christian church of Fullerton is indebted for the cozy, attractive house of worship it now occupies. A well known religious periodical in speaking of him recently said: “This religion of his is not of the ‘holier than thou,’ sanctimonious sort, but the honest, rugged, straightforward kind that never parades itself, yet everywhere wins the respect of the world.”

His faith is the kind that never parades itself? The newspaper he was bankrolling ran a front page “article” extolling the virtues of Mr. Chapman.

“Mr. Chapman resides at his beautiful, though unostentatious, home; busy with material affairs, hospitality and good deeds.“

His “unostentatious” house had 13 rooms.

“He has been justly termed ‘The Orange King of the World,’ and this he does not resent.”

Then, as now, powerful men like to have a fawning press. Edgar Johnson of the Tribune would not bend the knee to “Czar Chapman.”

Prohibition

The sale of liquor remained (mostly) illegal in Fullerton, following an 1894 county ordinance. There was an active Women’s Christian Temperance Union and an Anti-Saloon League, and they involved themselves in county politics.

In 1902, a Jo Smith of Fullerton was arrested, charged, and found guilty of violating the county liquor ordinance by selling liquor.

Perhaps adding some fuel to the fire of the liquor question occurred when attendees of a temperance meeting of the State Anti-Saloon League at the Fullerton Methodist church were interrupted by screams. Apparently, a Mr. J.J. Grogan had returned home intoxicated and attempted to burn down his house.

One result of incorporation in 1904 was that the newly elected city trustees could either allow or ban saloons. Those opposed to saloons included members of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), some local pastors, and the Anti-Saloon League.

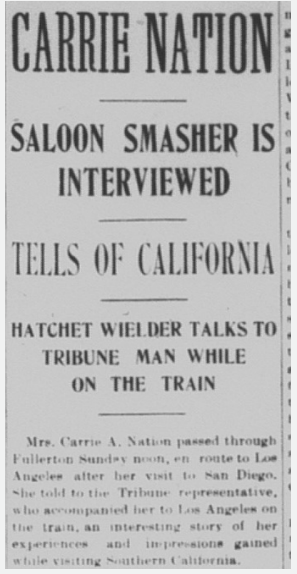

Famous prohibitionist Carrie Nation passed through Fullerton in 1903 and was interviewed by Tribune editor Edgar Johnson.

There was a highly publicized trial against a J.A. Kellerman who was accused of serving liquor in Fullerton as part of a Nationalist Club meeting. He was ultimately not convicted, as there was a hung jury.

The newly-formed Board of Trustees decided to put the question to a town vote as part of a larger city election.

In the newspapers leading up to the election, the Tribune printed editorials for and against prohibition.

Ultimately, a majority of residents voted to allow saloons downtown. However, two years later, in 1906, the town voted to outlaw them.

This was the result of years of organizing by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League.

In 1909, when the liquor question again was put to a vote there was overt voter suppression of Mexicans: “A number of Mexicans who, it is believed, were anxious to vote for license, were challenged, frightened, and not allowed to vote, on the grounds that they could not read, etc.”

The town again voted “dry.”

Education

In 1902, Fullerton had a grammar school and a high school, with an enrollment in the hundreds. Neither of these buildings exist today.

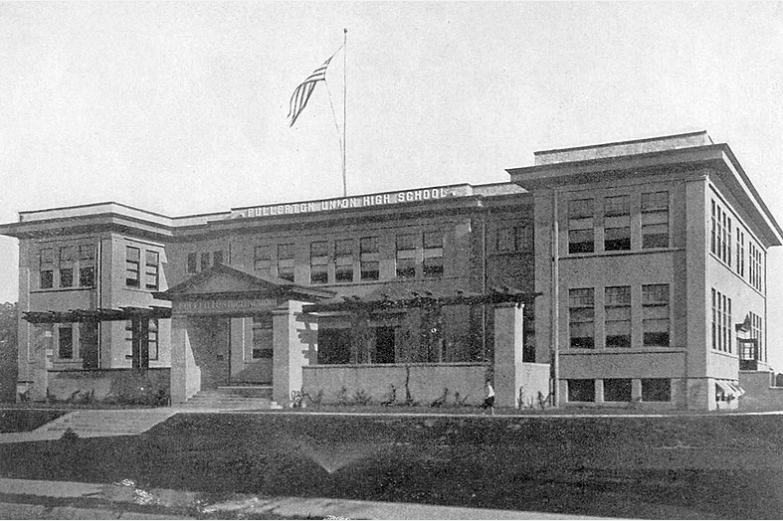

In 1906, voters approved the site for a new high school to be built on Commonwealth Avenue, where Amerige Park is today. The community was outgrowing the first brick high school building on Lawrence Ave. near Lemon.

The new high school was completed In 1908.

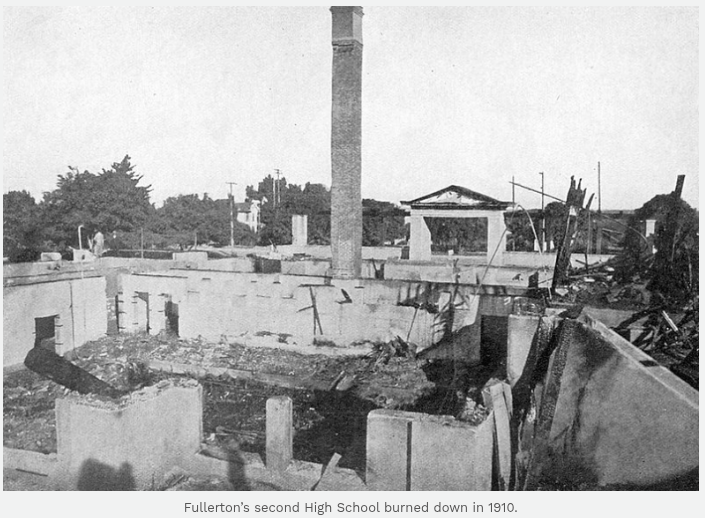

Unfortunately, in 1910, the building burned down.

Following this tragedy, the community began plans for a new high school, which would be built on Chapman Ave–where the high school still stands today.

In 1908, a seemingly normal article about the sudden death of W.R. Carpenter, former Fullerton High School principal ended up revealing a scandalous story about how Carpenter left his wife for the widow of the local Baptist minister.

Apparently, Carpenter married a Mrs. French Chaffee (widow of the Baptist minister) at sea when he was also married to another woman. After Carpented died, Mrs. French sued Carpenter’s first wife for money that she claimed she had loaned to her “husband.” Ultimately, French Chaffee’s claim was denied in court.

Meanwhile, the Tribune got its hands on some steamy love letters written by Carpenter to French Chaffee, and published some of them–creating quite the local scandal.

Agriculture

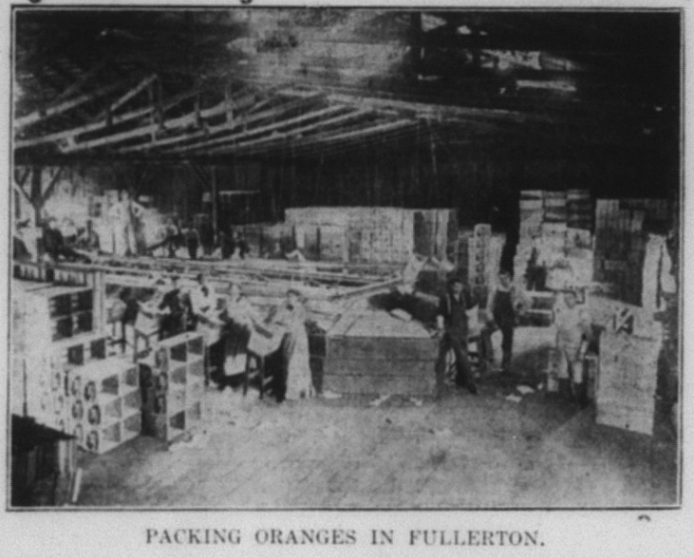

The citrus industry was booming and growing. In 1903, there were nine packinghouses in Fullerton along the Santa Fe railroad tracks. The downtown was surrounded by acres of orange and walnut groves, plus a smattering of other crops. Some groves were relatively small, while others were massive.

The most successful grower in 1902 was Charles C. Chapman, whose Old Mission brand Valencia oranges fetched the highest prices. Chapman’s ranch encompassed over 300 acres. In 1901, he shipped 130 carloads of oranges.

“C.C. Chapman, owner of the Santa Isabella ranchos and Orange groves, holds the highest record for prices obtained for oranges in the United States–$15.05 per box, besides being the largest individual grower and shipper of oranges in California,” the Tribune reported.

By the early 20th century, the orange industry was not functioning by the ordinary rules of capitalism and competition. Instead, the growers, shippers, and marketers were pooling their resources through Fruit Exchanges to eliminate the lower prices caused by competition.

“In this amalgamation the fruit exchanges and the independent shippers are to participate, irrespective of past differences, and the fierce competitive battle for supremacy in selling markets is likely to be replaced by a well-organized central sales agency, through which all independent and all exchange fruit will be marketed by a single board of control,” the Tribune reported.

This citrus conglomerate was initially called the California Fruit Growers Exchange, and later Sunkist.

Sunkist was essentially a union for the growers. Meanwhile, a 1904 article in the Tribune written by “one of the laborers” urged the workers to form a union of another kind–a worker’s union.

Here is the full text of the above (right) article:

“The Tribune has received a communication signed “One of the Laborers,” which advocates increased pay for ranch laborers in this section and their organization into a union to attain that object.”

The communication, addressed “To Whom it May Concern,” begins by stating that the American laborers in the Placentia district have a grievance in regard to their monthly pay. The writer says that the workers want a reasonable price for their day’s work, and cites the action of the Ventura laborers who organized a union, and decided not to work for less than $30 a month. The advantage of a union is then urged, and the local workers are called upon to organize for the purpose of getting their “price.” The communication declares that they now get 95 cents a day, which is denounced as a “regular outrage.” The warning is made that the workers will not stand for this “slavery any longer than the present time.”

After commenting that the hired man is “looked down on, snarled at,” the communication states that he is often forced to sleep in the barn, and concludes as follows:

“Boys, what do you think of that? We are not permitted to sleep in the house after a hard day’s work. We are brothers in Christ Jesus, born of one flesh and blood, and we ought to have a tender feeling for all. But after all of that the cold-hearted rancher sends his hired man to the barn to sleep with the living creatures that inhabit therein.”

On the same page as the above article was another entitled “The Chapmans Entertain Their Friends and Neighbors”:

Here is the full text of that article:

“Strictly the event of all social events in Placentia was the reception given by Mr. and Mrs. C.C. Chapman Thursday evening to their friends, neighbors, and strangers as well, of Placentia. The invitations were universal showing the good spirit and kindliness of the host and hostess, and the acceptance was almost universal. The guests were received by Mr. Stanley Chapman and his sister, Miss Ethel Chapman, and afterward by Mr. and Mrs. Chapman and Mrs. Hatchill, assisted by Mrs. McFadden and Mrs. Bradford. An orchestra occupied the music room and provided music throughout the evening. After cordial greetings on every hand the guests were given the opportunity to inspect the beautiful rooms on the first floor, consisting of library, reception hall, music room, dining room, breakfast room and kitchen. The rooms on the second floor were then shown. The guests were then invited to the third story which proved to be a hall strictly in keeping with the rest of the house. Here the guests were seated and most thoroughly enjoyed an entertainment.

The above contrast between the situation of the workers and the lavish mansion of Chapman, the mayor and wealthiest orange grower, speaks to the social divisions of the day.

Water

In order to make this agricultural economy thrive, water had to be obtained and regulated. The company which oversaw allocation of water from the Santa Ana River and all the major irrigation channels in north Orange County was the Anaheim Union Water Company, which sometimes had legal fights with water companies to the South who also drew from the Santa Ana River, such as the Santa Ana Valley Irrigation Company.

These were private companies whose Board of Directors tended to be owners of large, local ranches. Water rights (also called riparian rights) were a really big deal—water is life, and profits for farmers. Around 1901, these two water companies met together to bring legal action against a Mr. Fuller, “the Riverside county land-grabber” to prevent his taking water from the Santa Ana River. This would be one of many ongoing legal battles over local water rights.

In the meetings of the AUWC, there was discussion of purchasing the water rights of James Irvine, the man whose descendants founded the Irvine Company, which now owns the city of Irvine. In those early days, “maintaining an accurate division of the water [was] difficult if not impossible to devise.”

Meanwhile, the Anaheim Union Water Company and the Santa Ana Valley Irrigation Company cut a deal to share water rights. Mr. G.W. Sherwood, a sometimes AUWC Board Member who liked to write lengthy articles in the Tribune criticizing those who disagreed with him, took issue with the deal. To which Samuel Armor of the Santa Ana Valley Irrigation Company replied: “G.W. Sherwood seems to be afflicted with a diarrhea of words accompanied by a costiveness of ideas. For two years or more he has been filling the papers west of the river with misrepresentations and insinuations against the S.A.V.I. Co. until his followers have come to believe the the people on this side are equipped with hoofs and horns and forked tails.” To which Sherwood replied: “I have always taken pleasure in setting Armor right, when he gets tangled up in the mazes of his own alleged erudition…With regard to the proposed division of water, Armor’s premises are false and his conclusions are wrong.”

Like any political entity vested with power, the AUWC was occasionally hostile to journalists who were critical of its policies. In 1903, the Board of Directors passed a resolution excluding reporters from their meetings. Shortly thereafter, the Tribune got word that an important report had been suppressed, to which Tribune editor Johnson replied: “The best way would be to permit the reporters to attend the meetings, then the reports and proceedings would not be suppressed.”

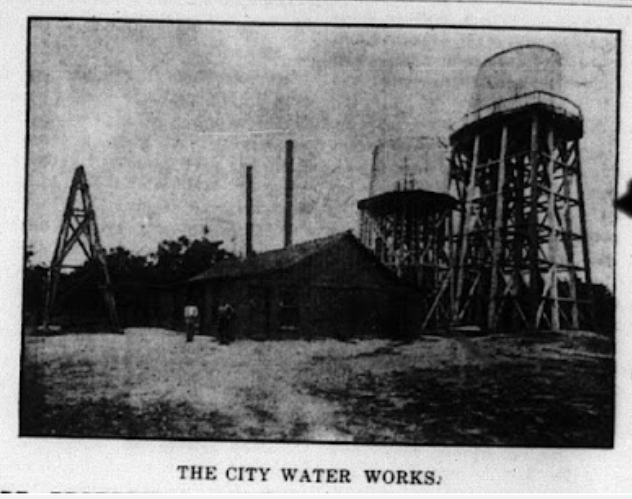

Perhaps the most contentious local water issue of 1906 was the question of whether the city would buy the town’s privately-owned Water Works (a pumping and storage plant) from its owners, the Adams-Philips Co. This issue created much public debate over the economic and philosophical merits of public vs. private ownership of utilities, a debate that feels relevant today. Prior to the election, it appeared that the majority of the citizens of Fullerton favored city ownership of the water works.

Ultimately, however, the issue went to a vote and was defeated. Tribune editor Johnson mused: “with the present plant owned by millionaires and in operation…the longer a city delays in acquiring public utilities, the more expensive becomes the undertaking.”

A group calling itself the Citizens Protective Association organized much of the opposition to the water bond issue.

In 1907, a seven year-long lawsuit upheld the water rights of the two Orange County companies, the Anaheim Union Water Company and the Santa Ana Valley Irrigation Company against a Riverside rancher named Fuller.

Fullerton rancher Charles Chapman was criticized by the Tribune (and apparently his neighbors) for changing the course of a waterway to protect his crops from flooding, meanwhile causing other ranchers’ properties to experience flooding during a recent storm.

In 1908, the Anaheim Union Water company completed the Yorba Reservoir, (later known as Yorba Linda Lakebed Park). The reservoir was located near Lakeview Avenue in Yorba Linda.

Oil

Starting in the late 19th century, several oil discoveries were made in the hills north of Fullerton, as well as in the Brea-Olinda area.

Early drillers included the Puente Oil Company and the Santa Fe railroad company.

Next, the Graham & Loftus company entered the field drilling “some of the best spouters in the Fullerton field, some of them going as high as 3,000 barrels a day,” the Tribune reported.

Then followed the Columbia oil company, the Fullerton Consolidated company, the Fullerton Oil Company, the Olinda Oil company, The Brea Canyon Oil Company, and the Union Oil Company.

Much of the Fullerton oil was piped to San Pedro by the Union Oil company’s 4-inch pipe line, a distance of 30 miles, and from there the company shipped to San Francisco for refining and other purposes.

By 1903, the Fullerton field was producing monthly nearly 125,000 barrels of oil.

Around this time, the Murphy Oil Company screwed the Bastanchury family out of oil they were entitled to.

The story is told in more detail in an article from the web site Basques in California:

“In 1903, the Murphy Oil Company leased the West Coyote Hills lands from the Bastanchury Ranch to dig for oil. One year of excavations found them hot mineral water at 3,000 feet. As one of the oil workers later confessed, they found an oil well at 3,200 feet but covered it up. In 1905, Murphy bought off from Domingo Bastanchury more than 2,200 acres in the surroundings of La Habra, at $25 an acre. Allegedly, Murphy assured Domingo before the acquisition, that those lands held no oil. Time later, the Los Coyotes Hills area became South California’s largest oil field.”

As time went on, the larger companies used their power to buy out smaller companies.

“The Fullerton field from Olinda to Brea Canyon presents an extremely busy appearance,” the Fullerton News stated. “As far as the eye can reach, new derricks rear their heads. Lumber and rigging are hauled in large quantities and the largest force in the history of the field is employed.”

Social and Business Clubs

At the turn of the century, around 6 million Americans were part of fraternal organizations. Fraternal organizations were a big part of the social life of Fullerton. The most prominent of these were the Masons, whose members included Dr. George Clark, William Berkenstock, William McFadden, A.A. Pendergrast, Otto Des Granges, and other prominent community members.

Another fraternal order, The Odd Fellows, had members who included William Goodwin, Edgar Johnson, Edward Magee, August Hiltscher, W. Schumacher, James Conliff, and others.

Local businessmen organized a Board of Trade in 1902 whose directors included Jacob Stern (co-owner of Stern & Goodman general store), William Brown, T.B. Van Alstyne, E.W. Dean, and V. Tresslar. Among the first matters taken up by the Board was securing electric lighting downtown, protecting the town against fires (the Fullerton Fire Department would not be organized until 1908), improving sidewalks and roads, and devising “a system of keeping tabs on any dead beats who may reside in the county or come this way…for mutual protection of our business men.”

A Chamber of Commerce was also formed, which seems a bit redundant with the Board of Trade. Its officers included Charles C. Chapman, Edward Amerige, and other prominent businessmen.

Religion

By 1902, there were at least three churches in town, all Christian. A Baptist Church, a Presbyterian Church, and an M.E [Methodist Episcopal?] church. In addition to fraternal organizations and schools, churches allowed for social interaction among the townspeople.

Homelessness

Edgar Johnson’s attitude toward the homeless was particularly harsh, and not that different from the attitudes of some today. Below are some excerpts of articles from the Tribune:

“Orange County Constables are having considerable trouble with hobos who infest its towns. Constable Llewellyn of Anaheim has been particularly active of late in making arrests.”

“Anaheim is not alone in being bothered by these wanderers. They abound in Fullerton and vicinity in almost as great an extent as in Anaheim. The experience with some of those arrested in the town down the road is evidence that these tramps are not only an obnoxious but in some cases a dangerous element in the country.

“Tramps are coming into Los Angeles and Orange counties in squads of forty and fifty. Every freight and passenger is loaded down with hobos and the trainmen are kept busy at every stopping point in vain endeavors to keep the brake beam artists off the cars.

Racism

By the turn of the 20th century, Japanese farmers and farm labor had replaced much of the Chinese labor that was curtailed by the Chinese Exclusion Acts. Dredging up the same arguments used to justify Chinese Exclusion (essentially, “they’re taking our jobs and doing better at business than we are”) white Californians agitated for excluding Japanese immigrants as well.

A 1907 Tribune article called “Japs Still in Town,” describes how a committee sought (apparently unsuccessfully) to run some Japanese people out of town, presumably because they were Japanese.

Here are a couple paragraphs from the article:

“Sunday afternoon a number of young men about town decided to go to the house where five or six Japanese reside at a late hour Sunday night with the intention of driving them out of town. Frank Claudina overheard the conversation of two or three of the brave lads and offered to pay the whole bunch $5 a head and also pay their fines if arrested, if they would go to the house and manage to get even one Jap out of the city. They did not take Frank’s offer, but declared that they would make good and hustle the foreigners out of town that very night.

This anti-Japanese sentiment found a welcome home in the pages of the Tribune, as shown by the following excerpts:

“While there has been no open declaration of hostilities there is war between the Japs and the whites of southern California.

“The Jap now clashes with the white, whether it be as a producer and shipper of vegetables, as a wage earner in the garden or orchard or as a laborer in other lines. This competition is becoming so strong that in some sections civic organizations are said to be preparing to appeal to the citrus growers and packers to employ none but Americans.”

Aside from racism, part of the white resentment against Japanese farmers stemmed from the success of Japanese farmers, both at growing and organizing their business.

“The Nipponese may not possess any great inventive genius, but they have not overlooked the co-operative methods of fruit and vegetable men. With a large acreage of farming land under their control they are preparing to adopt, and in some cases have adopted the co-operative marketing method of the Americans,” the Tribune reported.

Tribune editor Johnson re-printed an article by a Mr. Robbins, which argued that “The Japanese Must Go.”

“The question of Japanese exclusion was also being discussed at the national level with a Congressman Hayes introducing a bill “providing for the exclusion of the Japanese from this country, except certain favored classes,” the Tribune stated.

“As a matter of fact,” the article states, “the bill provides for excluding not only Japanese…but all orientals of the less desirable classes in other countries than Japan and China.”

“There is no doubt where the Pacific Coast stands on this question of Oriental immigration. All of the western members met together recently and agreed to support the Hayes bill, or at least the principles in general which it advocates,” the Tribune reported. “The Associated Chambers of Commerce of Orange County is going on record against Japanese immigration, against encouraging the Japanese to settle in Orange County, and against the sending of Orange County literature to the Orient.”

This anti-Japanese agitation would ultimately culminate in various exclusionary policies, including the 1913 Alien Land Law in California, which severely restricted the ability of Japanese (and other Asian immigrants) from owning or leasing land.

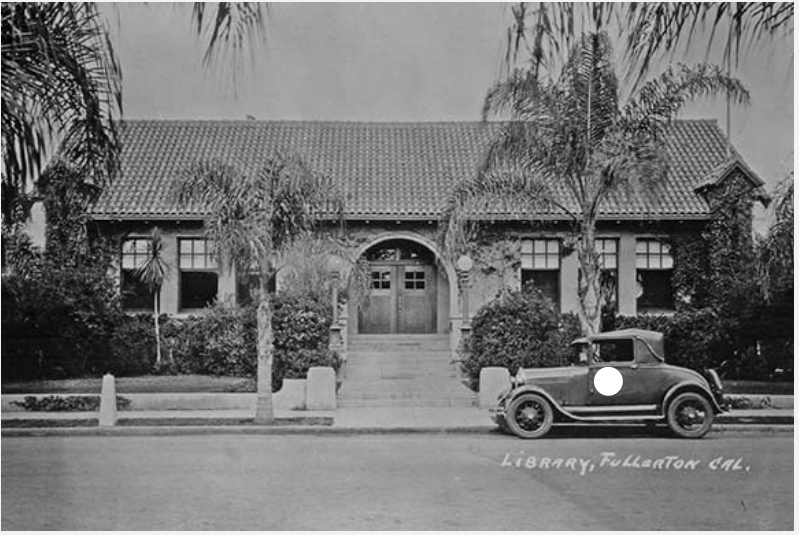

New Library

In 1907, Fullerton’s first real library, built with funding by industrialist Andrew Carnegie, was completed at a cost of over $10,000. The Library was on the site where the Fullerton Museum Center is today.

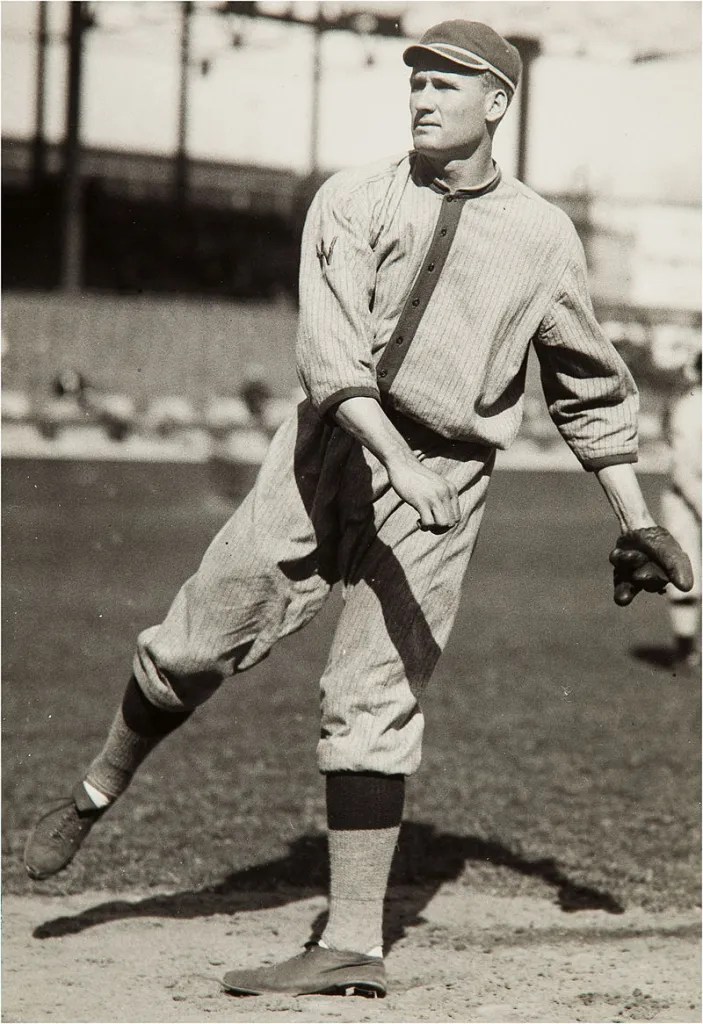

Sports

Walter Johnson, a future Hall of Famer, had been a pitcher at Fullerton High School. He went on to play for the Washington Senators, and became a source of pride for Fullertonians.

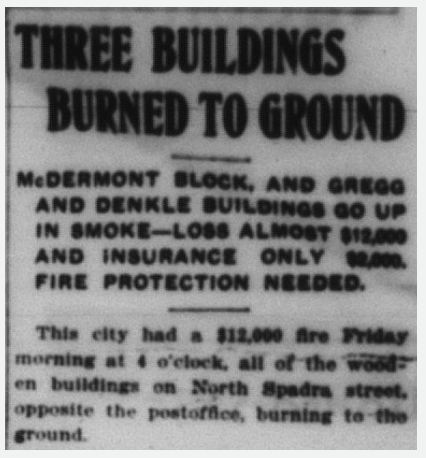

Fire

In 1908, a large fire destroyed three buildings downtown.

This fire prompted the citizens of Fullerton to organize the first volunteer fire department, to raise money for fire protection, and to consider municipal ownership of the waterworks downtown.

Health

In 1903, Fullerton’s first hospital opened. The Tribune called it “an up-to-date establishment and the best institution of its kind in Southern California. An efficient corps of nurses are in attendance at all times, so that patients of this hospital receive the best attention and care, which has already made the reputation of this hospital as one of the best.”

Deaths

In 1902, William “Big Bill” McFadden, died at age 62. Originally a schoolteacher, McFadden came to California in 1864, and served as Superintendent of Schools in Santa Ana. In 1869, he became a pioneer of citrus farming and was the second orange rancher in Placentia. He helped organize the Southern California Fruit Exchange, the Fruit Growers Bank, which then became the First National Bank of Fullerton, the Anaheim Union Water Company (on which he served as president and as a director). McFadden was a prominent figure in the local Democratic Party and was a representative from Orange County at the national Democratic convention of 1900.

The pallbearers at his funeral were Edward R. Amerige, Alex Henderson, Richard Melrose, Elmer Ford, Henry Lotz, and A.S. Bradford. The local bank and other stores closed for his funeral. He is buried in the Anaheim Cemetery.

In 1906, Fullerton pioneer rancher Henry Hetebrink died. His son John would later build that big old house (now vacant) on the Fullerton College campus, at the corner of Chapman and Berkeley.

In 1909, pioneer Fullerton resident Domingo Bastanchury passed away.