The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Fullerton had been founded just three years prior, in 1887, by the brothers George and Edward Amerige, in the waning days of a real estate boom that saw Southern California’s population explode and dozens of new towns spring up.

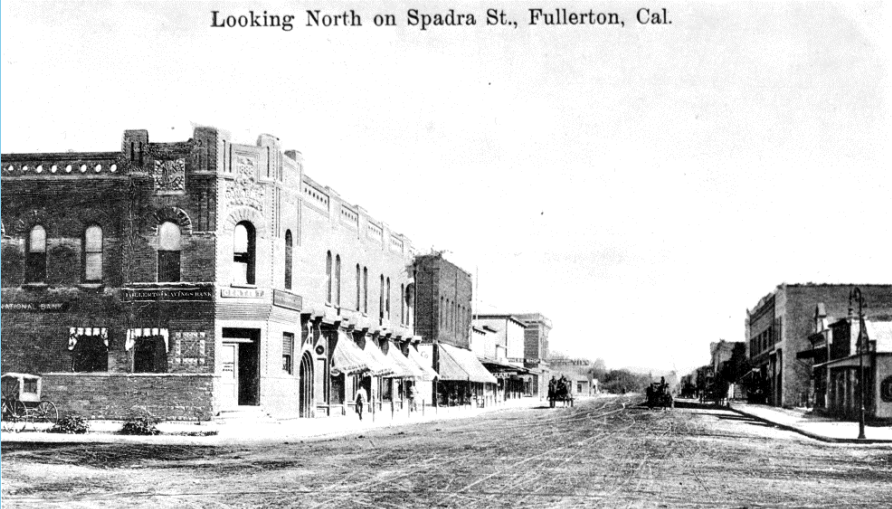

Fullerton in the 1890s was a small but growing town with an active downtown surrounded mostly by farms growing oranges, walnuts, lemons, and other crops.

Downtown, there was Alex Henderson’s blacksmith shop, William Starbuck’s Gem Pharmacy, Stern & Goodman’s General Store, the St. George Hotel, the Santa Fe Train station, and a handful of other business buildings.

Law and Order

Fullerton would not incorporate as a town until 1904, so in the 1890s there was no city government, police department, or fire department.

On weekends, those who liked to drink and party would come to Fullerton’s handful of saloons because of the lack of law enforcement, which led to situations like the following printed in the Fullerton Tribune newspaper:

“One result of having police officers in Anaheim who will not permit rowdyism and vulgarity on their streets, may be seen nearly every Sunday in this village. Men who have imbibed too much of the ardent, but who dare not make a noise in the streets of their own city, come over here and indulge in conduct which in a village having police officers would result in their arrest and punishment. Moral: Let us have a constable in town to keep order.”

“A number of roughs, hailing from everywhere, make it a point to come to Fullerton every Sunday, and after imbibing a library quantity of tarantula juice proceed to paint the town a bright, brilliant, carmine tint. They do this with the knowledge that we have no peace officer in this section, and accordingly they have no fear of arrest. We need a constable and a justice of the peace. Anaheim, a small village a few miles south of here, has two of each.”

Saloons!

The saloons in town quickly became the target of two local prohibition groups–the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Law and Order League. The liquor question would create serious divisions in the town.

Things started peacefully enough, with the local WCTU asking merchants and saloon keepers to sign an agreement to close their businesses on Sunday.

In 1894, because Fullerton was not yet incorporated as a town, the main governing political body was the county Board of Supervisors. In April, anti-saloon activists circulated a petition which they presented to the Supervisors in hopes of getting them to pass an ordinance outlawing saloons in Fullerton. At the same time, saloon owners circulated their own petition.

The Supervisors passed an ordinance of questionable legality, “compelling the saloon-keepers to remove all chairs, card, billiard, and pool tables and have nothing whatever for people to sit on,” the Tribune reported. “The saloon men are not at all pleased with this ordinance, hence the move to have it declared illegal or unconstitutional.”

In early May, the Supervisors took further action, refusing to grant any saloon licenses for Fullerton.

Following this decision, saloon owners took humorous action, posting the following notices on their public water troughs: “No prohibitionists allowed to water here.”

Things evidently got so heated that something as innocuous as a local school board election divided the town on the saloon question, and the Law and Order League brought out Orange County Sheriff Theo Lacy to keep the peace.

Meanwhile, the saloon owners won a legal victory as a Judge ruled against the legality of the Supervisor’s anti-saloon ordinance.

The Law and Order League responded by having all of the Fullerton saloonkeepers arrested “on a charge of selling liquor without a license.” Whether they were “arrested” by vigilante action or legally arrested is unclear.

We do know that at least three saloon owners were brought before a judge in Anaheim on the charge of selling liquor without a license. They were all acquitted.

Education

In 1889, local voters approved a bond issue of $10,000 to build a four-room brick elementary school building on the northeast corner of Wilshire and Harvard (now called Lemon) Avenues. Landscaping was done by students and teachers.

At the end of 1890, the first class graduated from the new school, consisting of just one pupil, Grace McDermont.

A high school would take a couple more years to come about.

“In the summer of 1892 William Starbuck and Alex McDermont canvassed the northern part of Orange County, hoping to transform educational ideas into action,” Louis Plummer writes in his history of Fullerton Union High School, “During the spring of 1893 these activities bore fruit in the form of a request to the county superintendent of schools to call an election for the organization of a union high school district.”

An election was held, and voters favored the creation of a new high school. The first trustees were William Starbuck, A.S. Bradford, B.F. Porter, and Dr. D.W. Hasson.

W.R. Carpenter was the first principal. At first, the new high school rented a room on the second floor of the Fullerton elementary school building, located at the corner of Wilshire and Harvard (now Lemon) avenues.

The Fullerton Union High School district first consisted of the territory of the elementary school districts of Buena Park, Fullerton, Orangethorpe, and Placentia.

Fullerton Union High School opened for classes in the fall of 1893 with eight students. Classes taught by Carpenter that year included Latin, physics, algebra, geometry, history, and English.

According to Thomas McFadden (class of 1896), “…during all the years I attended the Fullerton Union High School I drove back and forth with a horse and cart. All other students had to provide their own transportation.”

Worthington Means, class of 1898, said, “On the back boundary of the school grounds was located what would be a curiosity nowadays, namely, a shed where we could tie our horses.”

Enrollment in the Fullerton Union High School grew from 24 in 1896 to 62 in 1906, when Delbert Brunton became principal of the school.

“During that first summer he [Brunton] spent much of his time upon a bicycle visiting the homes of all eligible students whose names and residences he could learn. The school had not been completely accepted in all parts of the community as a permanent institution. It had added to the tax burden. The need for an educational program above the eighth grade was not universally recognized. Because of these conditions Brunton’s reception was not always cordial and results for the first year were not those for which he had hoped,” Plummer writes.

Immigration and Chinese Exclusion

The completion of the trans-continental railroad in 1869, which had relied heavily on Chinese labor, created a lot of job-seeking Chinese immigrants. These immigrants were a Godsend for large fruit growers in California, as Chinese laborers would work for very low wages.

According to the California Bureau of Labor, Chinese workers constituted around 80 percent of the agricultural laborers in the state in 1886. Low-paid Chinese labor was a major factor in the early economic success of the California fruit industry.

However, anti-Chinese sentiment became federal law in 1882 with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which curtailed Chinese immigration to America and made official what was already widely practiced. Chinese were forbidden from becoming U.S. citizens.

The Geary Act of 1892 continued the provisions of the Chinese Exclusion Act and also provided for massive deportation of Chinese from the US. The language of the Geary Act is eerily familiar. It “forced the burden of proving legal residence upon the Chinese, and required that all Chinese laborers register under the act within one year of its passage.”

During the years when this anti-Chinese activity was most acute (1893-1894), the United States was in the throes of a major economic depression. During this economic turmoil, Americans sought a scapegoat for their troubles, and found that scapegoat in Chinese workers.

Here in Fullerton, Chinese workers had been a presence since the beginning of the town. Bob Ziebell writes in Fullerton: A Pictorial History, “George Amerige says he installed the town’s first water system ‘employing Chinamen to do the excavation work on the ditches.’”

The Fullerton Tribune newspaper featured a running trend of articles dealing with the topic of Chinese Exclusion, all of which heartily supported it.

On October 7, 1893, Tribune editor Edgar Johnson reported that “Two Chinamen were arrested at Santa Ana Tuesday and taken to Los Angeles to go before Judge Ross on a charge of violating the Geary act by not registering within the time prescribed by law.” On Jan 6 of 1894, Johnson called it a “well-known fact that the Chinese do not make desirable residents in this country.” Edgar Johnson often refers to Chinese people with the racist (but commonly used) term “Chinamen.”

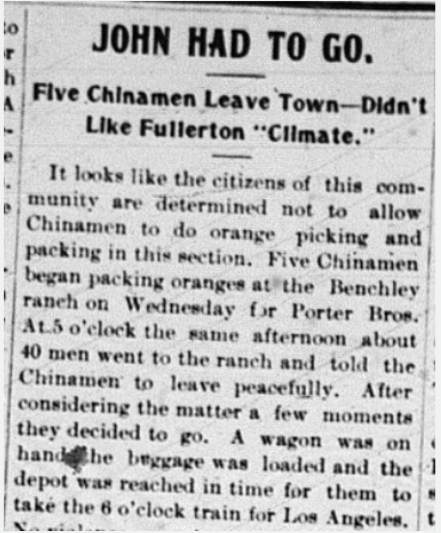

On February 17, 1894, Johnson reported an event that happened in Fullerton. Apparently a mob of 40 locals forced some Chinese workers to leave town.

Water

In 1893, water was mainly controlled by the Anaheim Union Water Company, whose board of directors consisted of large landowners and ranchers.

Six years prior, in 1887, the California state legislature passed the Wright Act of 1887, whose purpose was to give small farmers a fair shake by allowing them to band together, form public collectives called Irrigation Districts, and get water to where it was needed.

This was not how the Act was presented in the Fullerton Tribune. Reading articles from 1893 onward, one gets the impression that the sole purpose of the Wright Act was to unfairly tax water companies. It was met with near immediate outrage by the larger local ranchers, who in 1893 formed the Anti-Wright Irrigation League, which saw itself as a defender of taxpayers (Which taxpayers? One wonders.)

The stated function of the Anti-Wright Irrigation League was “the complete annihilation of the Wright Act.” Edward Amerige, co-founder and member of the Board of Directors of the Water Company wrote in the Tribune: “I see inevitable ruin and bankruptcy in the future if the Wright Act is not wiped out.” William McFadden, also on the board, took a more nuanced approach, writing, “I am in favor of the [Irrigation] District, but think the directors made a mistake in levying the special tax. I think the Wright Law would be the best thing for the people if successfully carried out, but if it cannot be done, wipe it out completely.”

The Santa Ana River and its irrigation ditches were protected by men called zanjeros, paid by the Water Company, to ensure the water flowed to its rightful owners: “The zanjeros were instructed not to deliver water to anyone not a stockholder and then not to exceed his stock limit.” These private water police were needed because some people still had the gall to partake of a local natural resource without paying.

Early in 1893, a “zanjero reported that the Chinese at the vegetable gardens north of town had been stealing water from the ditches.” One doubts the veracity of this report, as the Chinese, at this particular moment in American history, were the feared and hated immigrant group of the day. They would soon be run out of town by armed vigilantes.

In addition to taxes, part of the conflict between the Wright-created Irrigation District and the Anti-Wright League (i.e. the Water Company) had to do with the creation of a reservoir. The Irrigation District, presumably representing the interests of small farmers, sought to create a reservoir in the under-represented region of Yorba. The Water Company, presumably representing the interests of the larger ranchers, sought to create a reservoir in La Habra.

And then came the Age of Cement. Perhaps irrigation ditches were already being cemented, but the first mention of this increasingly popular trend appears mid-1894, when the Water Company hired contractors “for cementing the south branch ditch from Crowther’s corner to Brookhurst, 24,244 feet, and the East street ditch form Sycamore Street to Santa Ana Street, 3,300 feet.” More cementations will follow. The Romans would be proud.

If 1894 inaugurated the Age of Cement, 1895 brought the Age of Bonds. With cash flow relatively low, the Water Company began doing large-scale infrastructure projects (i.e. cementing more ditches). How will it pay for this? Why, with bonds: “Speaking of the bonds, Mr. Botsford said that Los Angeles capitalists were eager to purchase the whole issue.” This Mr. Botsford will turn out to be an enthusiastic (and controversial) advocate of bonds.

Edward Amerige emerged as the principal opponent of Mr. Botsford’s bond schemes. In an 1895 letter to the editor, Amerige wrote: “To increase the present great indebtedness of the company at a time when the water sales do not pay running expenses, let alone interest on outstanding notes and bonds, which now amount to $1000 per month, or there about, by cementing the Placentia ditch at a cost of $14,000, is suicidal. It looks as the though the company was run in the interest of 1 or 2 directors.”

Part of the push for more bonds and cementing had to do with a push to expand the territory of the Water Company. Amerige noted: “Who are the people who are clamoring for an increase of the present district? Mostly speculators.” This is a bit ironic because when George and Edward Amerige founded Fullerton, just 8 years earlier, they could be considered speculators. This conflict was really about settled speculators vs. new speculators. Ultimately, it was a conflict over resources.

Amerige’s critiques of the water board become more direct and angry as 1896 rolled on. In an article called “The Water Fight,” he writes: “In looking over the cementing that has been done in the water district I find that the greatest outlay and the most expensive ditches have been made in the vicinity of several gentlemen’s places, namely W.F. Botsford, Wm. McFadden, W. Crowther, and F.G. Ryan. Does this not seem a little singular when all of these gentlemen are directors in the water company?”

By 1897, conflict had developed between the Board of Directors of the Anaheim Union Water Company and Edgar Johnson. Apparently, after Johnson printed some articles criticizing the management of the Water Company, the board of directors decided to stop doing business with the Tribune, which caused Johnson to write an angry editorial in which he said, among other things: “Because a paper criticizes the board is no reason why business should be withdrawn.” As it turned out, it was.

Complaints continued from residents of the region of Yorba, particularly from a Miss Yorba, probably a relative of the famous Bernardo Yorba, who refused to accept $100 for a “right-of-way” for water to pass through her lands. The residents of Yorba seemed to increasingly get screwed in these complex water dealings.

When an election was held for a new Board of Directors of the Water Company, Johnson criticized the election as corrupt: “Forgery was used to carry out the program of the water ring.”

There were often legal battles began between rival water companies. For example, the Anaheim Union Water Company and the Santa Ana Valley Irrigation Company went to court to prevent ranchers from the San Joaquin Valley from trying to use water from the Santa Ana River.

As the 19th century drew to a close, legal (and sometimes physical) fights over water would continue.

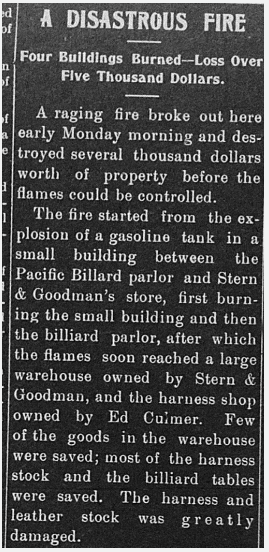

A Disastrous Fire

In 1898 a massive fire destroyed some buildings downtown, including part of Stern & Goodman’s store. At this time, Fullerton did not have a fire department. Instead, over 100 men and women pitched in to try to help extinguish the flames.

“At the time of the fire there was not a drop of water in the town tank but a bucket brigade was organized at once and was soon carrying water from the large storage tank on Commonwealth avenue, about 200 yards from the burning buildings,” the Tribune reported.

Fullerton’s fire department would not be organized until 1908, after another, even more destructive fire downtown.