The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library has microfilm from the Fullerton Daily News-Tribune newspaper stretching back to 1893. I am in the process of reading over the microfilm, year by year, to get a sense of what was happening in the town over the years, and creating a mini archive. Below are some news stories from 1932.

International News

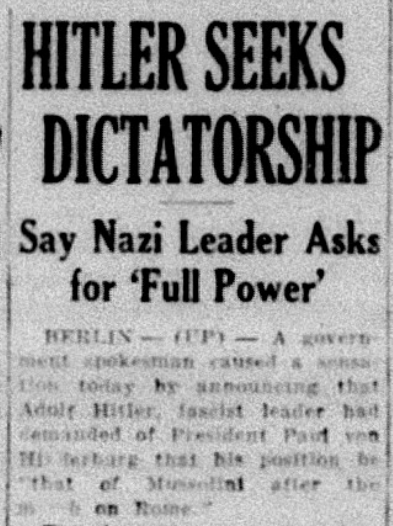

Internationally, fascism was on the rise in Germany, with Hitler’s Nazi party gaining a majority of seats in the Reichstag (Germany’s Parliament).

In Italy, the fascist Benito Mussolini had been in power since the 1920s.

In Asia, fighting between China and Japan in the international district of Shanghai in the so-called January 28 Incident prompted United States and European military involvement in brokering a peace deal. This was largely to protect American and European economic interests in China.

In India, Mahatma Gandhi ended a hunger strike in his long quest for independence from Great Britain.

National News

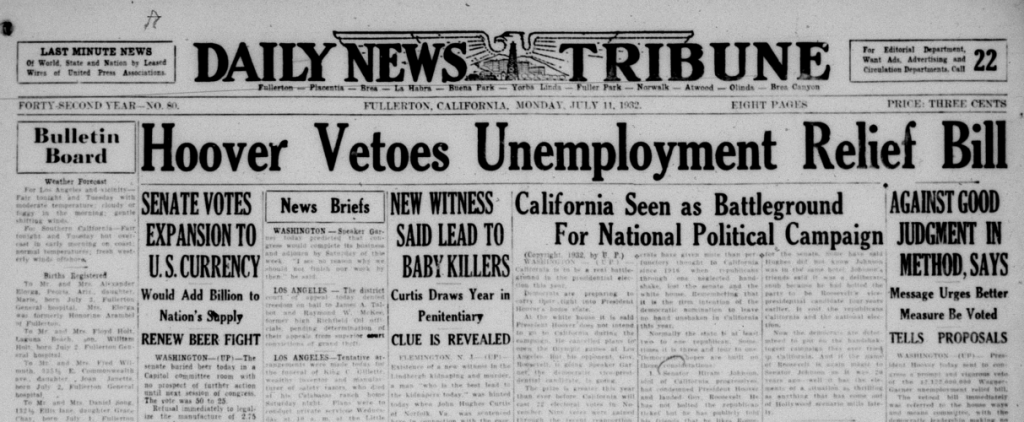

The biggest national news story was the election of Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He defeated Republican Herbert Hoover in a landslide victory.

California, which had long been a Republican state, went blue for the first time in years, although a majority of Fullertonians voted for Hoover.

The election was seen as a national repudiation of Hoover’s failure to improve the economic conditions of the Great Depression.

One major debacle of the Hoover administration was his use of military forces to clear a large encampment of tens of thousands of World War I veterans and their families who had marched to Washington DC, called the Bonus Army, who sought early cash redemption of their service bonus certificates.

In more sensationalistic news, the baby of famed American aviator Charles Lindberg, was kidnapped.

Depression

Roosevelt would not take office until 1933, and so the federal New Deal programs aimed at helping the millions of unemployed, as well as unemployment insurance and social security, did not yet exist. Thus, local municipalities with their limited budgets (which had taken a hit from declining property values caused by the Depression) were largely left to fend for themselves to tackle widespread unemployment and poverty.

To address local unemployment, the city council put a bond measure on the ballot to raise money to provide jobs in developing local parks and bridges. Unfortunately, voters turned down the bond.

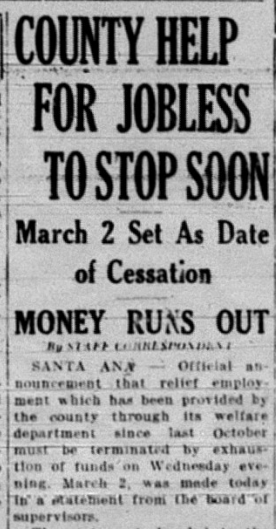

County programs for the unemployed also faced diminishing funds.

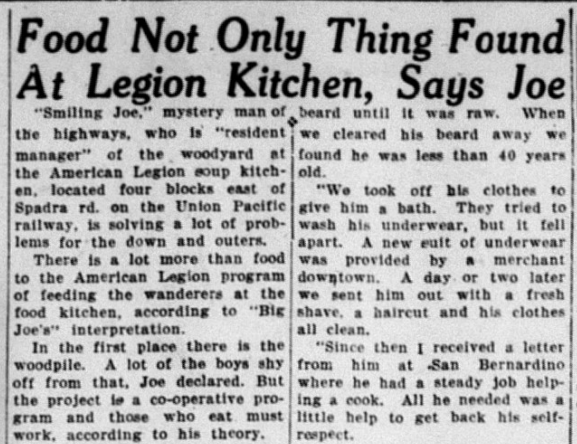

Thus, help for the homeless, unemployed, and hungry fell upon local groups like the American Legion, who operated a soup kitchen which offered food and (limited) lodging.

Another soup kitchen was operated by the Maple School PTA.

Tragedy Befalls the Bastanchury Ranch

The Great Depression proved disastrous for the Bastanchury family, owners of “the largest orange grove in the world.” Unable to pay their debts, the Bastanchury Ranch went into receivership, and lost most of their property.

This was a tragedy not just for the Bastanchury family, but also for the hundreds of Mexican citrus workers who lived in camps scattered across the ranch, who in 1933 would be subject to a mass deportation/repatriation.

This connects to a larger story about Mexican deportation and repatriation during the Great Depression which is told in the book Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s. As has unfortunately happened throughout American history, from the Chinese Exclusion Act to today, times of economic downturn have sparked scapegoating and calls for deportation of immigrants, both documented and undocumented.

The mass deportation of Bastanchury Ranch workers would not happen until March of 1933, but the forces of deportation and repatriation were already happening, as the article below explains:

“Cautioning his audience against signing papers or notes not fully understood, Raymond Thompson, Fullerton attorney, explained simple fundamentals of law last night at a meeting of the Mexican labor union of Tia Juana camp on the Bastanchury ranch.

Thompson’s discussion was translated into Spanish by Lucas Lucio of Santa Ana, recently appointed Mexican vice-consul of Orange county and county director of Mexican repatriation.

Legal procedure in regard to installment buying, mortgage payments and foreclosures and claiming of unpaid wages was explained by Thompson. The Mexicans asked questions on particular problems and three were discussed.

At the close of Thompson’s talk, Mrs. Lucille ward, Americanization teacher, introduced Lucio, who spoke on the work of repatriation and deportation of Mexicans to Mexico. While urging that Mexican citizens who still retain property or homes in their native country apply for repatriation, Lucio advised those who are employed in the county to remain here. Describing an impoverished Mexico with serious unemployment problems, Lucio stated that already of the 7,000 Mexican citizens resident in Orange county 2,000 have returned home since last August. Of these, three percent went by deportation and the rest voluntarily. It is expected that about 700 more Mexicans will return to Mexico this year before the repatriation movement stops.“

It was believed that deporting Mexican workers would give more jobs to white workers.

“Robert Strain and Tom Eadington, another packing house operator, declared that white crews would be given every opportunity,” the Tribune reported.

The Tribune published a couple articles which described life on the Mexican citrus camps, which I will reprint in their entirety below. Note to reader: These articles (while valuable historical documents) paint a much rosier picture of life in the camps than was the reality. For a more honest assessment of Mexican citrus camps at this time, check out my summary of historian Gilbert Gonzalez’s important work on this topic, Labor and Community: Mexican Citrus Worker Villages in a Southern California County 1900-1950.

“Sheltered in the hollow of a groove between green rolling hills covered with orange trees, El Hoyo (The Hole) camp, also called by reason of its peculiar location Escondido (Hidden Place), is at once the smallest and most picturesque of the north Orange county Mexican citrus camps contacted by Fullerton union high school immigrant education department.

A few hundred feet off the traveled path of state highway 101, a little dirt road takes a sudden circuitous, steeply downward course, and below in hilltops are the seven frail cottages composing Escondido. A half-dry creek bed meanders through the camp and provides countless flies. Touches distinctly foreign are provided by the lean cow tethered on a green slope, and by the motley array of bed springs, galvanized tin, logs and boards which go together to make up the houses.

Last week, joy permeated the Mexican families, because employment had been give all but two of the men. In one household, however, a family including a young woman with her two sons, her sister, a mother and step-father–not to mention the lean cow–are subsisting on $2 a week earned by the young woman, who works two 12-hour days doing washing, scrubbing, cleaning and general housework at the Dominic Bastanchury home. The cow provides milk which is pressed, patted, and dried into cheeses to be eaten whole or grated into tortilla “frijoles.”

In each small house of unfinished brown boards is the lean-to kitchen with its pan-dotted walls. Unlike the homes of the larger, more affluent Mexican camps nearby, the Escondido houses have few conveniences. Un-modern wood burning stoves of heaviest iron are used. The Mexican mother, surrounded by her two to 10 young ever-hungry children, will stand untiringly beside the stove, and patting and rolling thin rounds of flour-water and lard dough, will fling it on the stove top to bake into tortillas. Instead of bread, the tortilla at Escondido is the main fare, and eaten with water-cress and beans seasoned with chili-garlic sauce from a molcajete bowl, provides breakfast, luncheon and dinner.

A novel dish favorite with the Mexicans is boiled cactus. Paring off the prickly pear outer skin of the large, flat-leaved cacti, the housewife will dice and boil in salt water the inside portion, which tastes like green peas or beans.

In the absence of remunerative work, the men have spent their time since bankruptcy of Bastanchury company, by whom they are employed, in farming on small ground patches. To their village come each week a bread man from Corona, a meat man from Santa Ana, a Syrian bread merchant and a Los Angeles traveling grocer. Credit is extended in present conditions until work is obtained by the men.

Escondido was depleted in population recently by the return to Mexico of one of its families.

Twice a week Mrs. Lucille Ward, Americanization teacher, visits the little brown schoolhouse and teaches children and grown-ups alike the elementary principles of sanitation and education. Donna Felipe, who cleans and keeps neat the schoolhouse, is ancient in years and a grandmother to six boys and two girls, yet she displays an Americanized active thought, and discusses such current topics as birth control and the tenure law!

After a trip through the flower-bordered small houses, the return job takes one past a veritable picture book scene of slender eucalyptus and weeping willow in which is set a tall brown house overhung with climbing roses. Showers of yellow and deep pink flowers fling themselves over the shingled roof in undisciplined color. Shaded by the willow leaves, the garden is filled with roses and small plants of beauty–but there is an air or desolation. Donna Maria, well-loved Mexican housewife and “favorite” of the Americanization workers, died last summer and her home is left to her husband, who works on the ranch. Now left to bloom unaided, the garden was formerly a marvel of orderliness and the house exemplary of meticulous tidiness. Miss Druzilla Mackey, director, Mrs. Arletta Klahn Kelly, former teacher of the camp, and Mrs. Ward all have words of sorrow for the hospitable Donna Maria, prize pupil of “la escuela.”

In the main, Americanization is well accepted and its teachings to a degree are followed by the residents of the tiny hidden village.

Click HERE for more about the local Americanization program.

“Old Mexico and new California blend to compose the daily life in the Mexican camps which dot north Orange county, a tour of the camps with Miss Druzilla Mackey, director of immigrant education of Fullerton union high school district, reveals.

Before the rows of brown frame company-built houses the clothesline of each Mexican housewife wears its serape of drying clothes in a riot of color. Fat brown babies play on the doorsteps and marigolds and turnips thrive side-by-side in the front gardens of the homes.

Inside the home cleanliness is marked. Wood or linoleum-laid floors alone are scrubbed shining and spotless. Bed room and living room are frequently combined, and on the beds fluffy boudoir dolls made in Americanization school share honors with delicate cut-work and lace pieces which most Mexican girls delight to make. In one room corner is a cross or family altar, while in the more affluent homes the radio is found.

Baking tortillas and enchiladas, washing and cleaning occupy the time of the Mexican mother. While she retains the language and dress characteristics of her motherland, her daughters are products of public schools and wear the waved hairdress and modern garments of the American girl.

Monthly a trained nurse and physician visits the camps to hold a clinic. The Mexican bambino (baby) is dressed in shirts heavy with crocheting and hemmed in handmade lace. The young mothers anxiously request and put into effect suggestions as to sanitary care for their children, which are seldom ailing.

Miss Mackey, Mrs. Carmen Adams and Mrs. Anna Roy visit Pomona camp in Fullerton each week to instruct the residents in elementary English, housekeeping, sewing, and cooking. In La Jolla, Atwood, La Habra, Placencia, and at Bastanchury the camps serve as counsellors for their miniature communities which average 40 families.

A Mexican citrus worker is employed in this district between six and nine months each year, and earns about $2.50 a day. In Fullerton he pays about $15 a month for house, gas, lights, and water. In the idle months, the men of the family travel through the state in hope of finding additional work. On an average salary of $80 a month a family of from two to 10 children and in-laws with pet dog, cat and tame birds lives in comparative comfort. The young girls often assist in housekeeping and the boys seek whatever odd work they can obtain. The drawn-work and lace of the women in exquisite but they are not paid enough to warrant their selling it.

Each camp has between a dozen and 40 houses with community shower, bath, and outdoor laundry tubs. In La Habra, first rural camp and organized 10 years ago, the most affluent Mexicans are to be found. At La Jolla, a group of cement workers, citrus and general workers selected an unrestricted space of land and built their homes. Here is a typical Mexican community. Each house has its fence to keep the neighbors’ chickens away from the garden.

Except for church holidays and occasional wedding fiestas, there is little social life in the camps except for “school days” when the entire feminine population turns out to study household arts and learn hand crafts.

At present, lodges are popular and in the community halls hang charters of labor unions and social orders. In the past year, cement work has been so scarce that several families now contemplate returning to Mexico to take up homestead lands.

Boys of the colonies seldom complete high school and since minors are forbidden citrus work in this district, they spend their time playing rebote, or Mexican handball, and working wherever they can. The young girls and their mothers work on dresses, linens, and quilts. They throng the community building to spend their time sewing and studying. In Placentia, a young Mexican girls club is being organized under direction of Miss Rose Camers, resident teacher, by Fullerton, Placentia, and La Jolla girls. The 60 families in the La Habra camp are advised by Mrs. Jessie Hayden. They live in homes scattered over a hill and are distinctly separate from the independent homeowners of a neighboring hill. A substantial colony is in Atwood, and at Bastanchury several groups of families constitute the general camp, which is managed by Mrs. Lucille Ward. At Placentia, community gardening is a current project.

Education in opinion of Miss Mackey is a serious problem for the Mexicans. Scarcity of space at home, and the distance of the library or school are obstacles to education. Each member of a family is needed as a breadwinner and many difficulties beset the path of the young Mexican who aspires to more than a grammar school education.

An education attained, the student has still to face a racial prejudice in the business and professional world, she says. Unless parents and children are eager to undertake the struggle for higher education, it is not forced on them, since the odds are so great against success.

The state, county, local school system and the citrus associations combine to maintain Americanization schools and resident teachers. In addition to visiting teachers, Miss Macke makes frequent visits to each colony to note progress and assist in teaching.

Mrs. Arletta Klahn Kelly assists in work at Pomona colony, where she was until recently in charge. In recent years of depression, when other activities have been curtailed, the citrus industry still contributes to the camp work.“

Politics

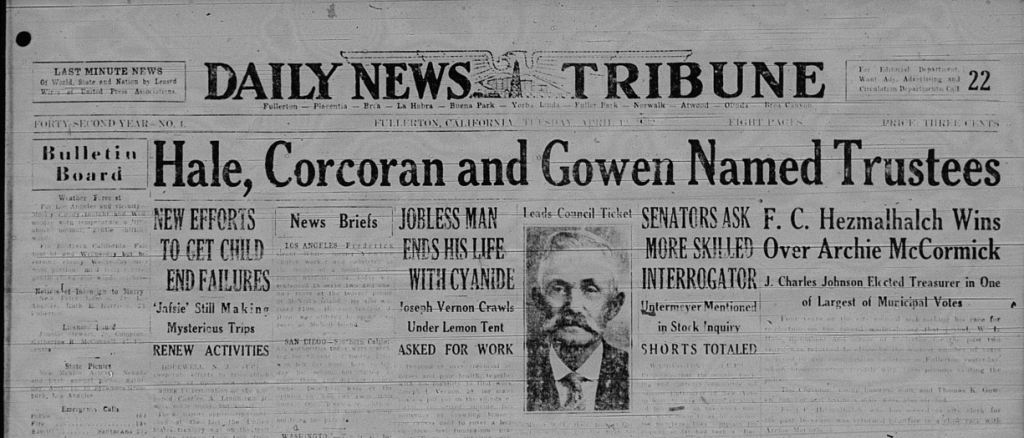

In local political news, Billy Hale, Ted Concoran, and Thomas Gowen were elected to the City Council.

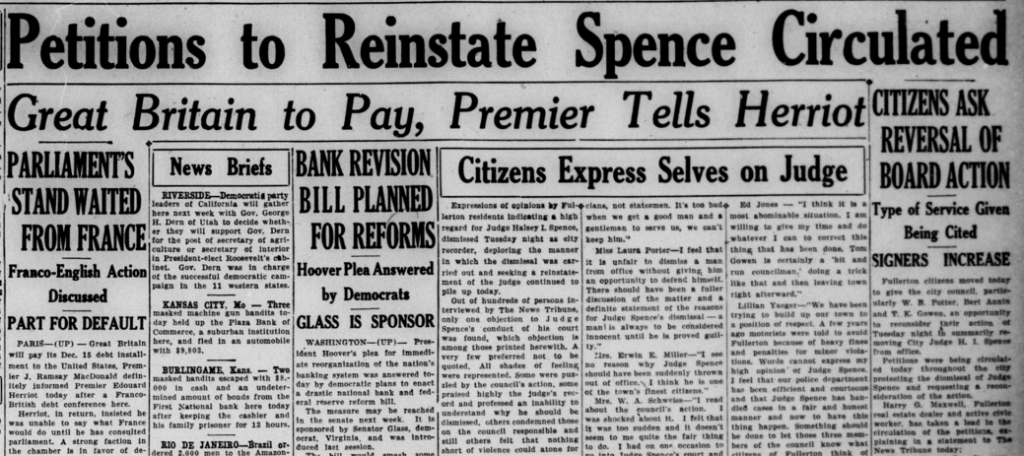

A local crisis occurred when a new council majority chose to dismiss local judge Halsey Spence, which prompted massive community backlash, and a petition to reinstate him. Stay tuned for more on this in 1933.

Education

In education news, Valencia Drive school was built.

Prohibition

Prohibition, which was enacted in 1919 with the ratification of the 18th amendment, was nearing its end. It would be repealed in 1933 by the 21st amendment. Prior to that, the Wright Act, which provided state enforcement of prohibition, was repealed by voters.

Fullerton, being Fullerton, kept its local ordinances making alcohol illegal.

This is pretty much what Fullerton did in 2016 after California voters legalized recreational cannabis, making dispensaries still illegal. Dispensaries are still illegal in Fullerton.

Crime

Local crime mainly involved robberies and burglaries, which is not surprising given the unemployment and poverty created by the Great Depression.

In Anaheim, the Mayor was murdered.

Culture and Entertainment

For entertainment and escape from their troubles, Fullertonians went to movies at the Fox Theater.

Fullerton hosted an annual Jacaranda festival, which included a bike parade and an air show.

Thousands attended a massive Armistice Day parade.

There was a kite contest.

Downtown businesses created elaborate window displays for an annual “Hospitality Night.”

An Easter event at Hillcrest Park drew thousands.

And there used to be something called Golden Rule Week, which I think should be more widely celebrated.

Sports

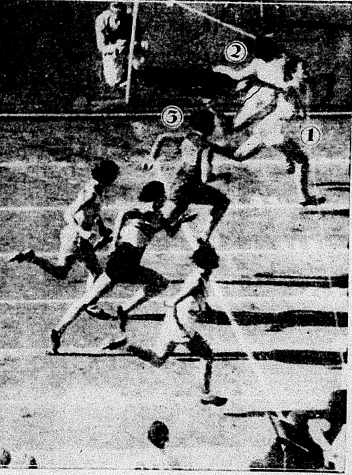

Los Angeles hosted the Olympics in 1932.

Fashion

Miscellaneous

And here are some miscellaneous clippings from 1932:

The above article describes how World War I veteran Jessie E. Houser was awarded the Purple Heart: “He was wounded July 19, 1918 at the battle of Soissons Chateau-Thiery while a member of Company 1, 26th infantry, First Division. He received a machine gun bullet in the leg. His citation for gallantry came when he was one of a part of three that captured a machine gun nest and brought back 13 prisoners. Houser also volunteered on a detail to bring machine gun ammunition to the front under heavy barrage fire…Houser, who came to Fullerton after the war, is a member of Fullerton post 2073, Veterans of Foreign Wars.”

Stay tuned for top stories from 1933!