The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Fullerton Observer newspaper was formed in 1978 by Ralph and Natalie Kennedy and friends to provide a more progressive counterbalance to the more conservative Fullerton News-Tribune and Orange County Register. The Fullerton Public Library has digital archives of the Observer stretching back to 1979. I am in the process of reading over each year and creating a mini-archive. Here are some top news stories from 1993.

Budget Woes, the Utility Tax, and a Recall

In 1993, Fullerton was represented on City Council by Mayor Molly McClanahan (a moderate Democrat), and councilmembers Julie Sa, Don Bankhead, Chris Norby, and “Buck” Catlin (all Republicans). Although, technically, city council is a non-partisan office.

Facing a budget deficit of over $4 million, City Council voted 3-2 to make $2 million in budget cuts, or about 71 positions. To make up the rest of the deficit, at two highly contentious meetings with hours of public comment, a divided council proposed a 3% utility tax, but later lowered it to 2%.

The first meeting took place In the Fullerton College Campus Theater and drew nearly 700 city residents.

The tax would be placed on businesses and residents for telephone, electric, cable TV, and water services. It had exemptions for low-income families, and placed a cap of $10,000 per utility per year charged to businesses.

“Led by organized opposition of the Fullerton Chamber of Commerce, which described the utility measure in literature circulated in the city and handed out before the meeting, as ‘the largest tax increase in Fullerton history!!,’ and a ‘cash cow scheme,’ many speakers argued for ‘farming out’ many directly operated city services to private operators,” the Observer reported.

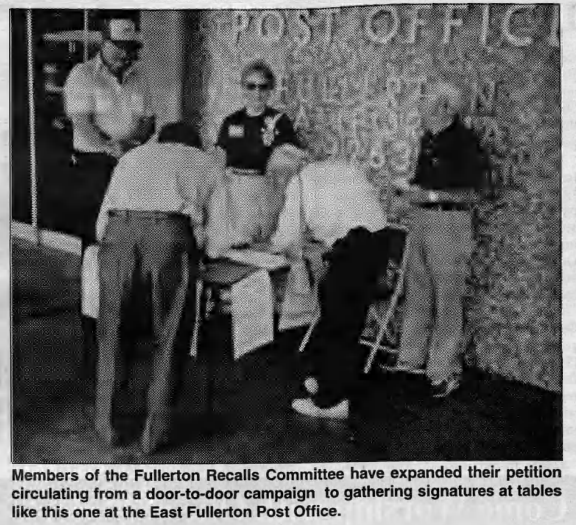

At the second public meeting, Council voted 3-2 to approve a lower 2% tax. Following this vote, McClanahan, Catlin, Bankhead, and City clerk Anne York became the targets of a recall effort, to vote them out of office.

Local attorney Joanne El Kareh and former Chamber of Commerce president Tom O’Neill sued the city, arguing that council acted illegally when it voted 3-2 to approve the utility tax. They claimed that [state] Proposition 62 requires a two-thirds, or 4-1, vote of the city council to impose a utility user’s tax.

City attorney Kerry Fox disagreed, stating, “So long as the levy of a utility user tax is for general fund purposes it (like all other excise taxes) is not subject to [a two-thirds vote at an] election under Proposition 62.”

Meanwhile, the recall campaign was in full effect.

Should the recall effort gather the required number of signatures, an election would take place in 1994. Stay tuned!

The Honor Roll Murder, Tagging, and a New Sheriff in Town

In 1993, one of the grisliest murders in local history took place, when five Sunny Hills High School students brutally killed Orange High School student Stuart Tay.

The killers were Robert Chien-Nan Chan, Kirn Young Kim, Abraham Acosta, Mun Bong Kang, and Charles Bae Choe of Fullerton. They were all convicted or pleaded guilty.

The Orange County Register called it the “Honor Roll Murder” because most of the killers were high-achieving students who planned to attend elite universities.

The shocking crime prompted a meeting of students and parents at the Sunny Hills High School gym.

“No one could come up with a plausible explanation of what caused the tragic occurrence…[or] how such a tragedy could happen in upper middle class families with high achieving, apparently model students headed for prestigious universities and professional careers,” the Observer reported.

Stay tuned for more on this case.

In 1993, I was a 7th grader at Ladera Vista Jr. High. What was popular among young teens in 1993? Super Nintendo/Sega Genesis, baggy pants, Air Jordan sneakers, oversized Looney Tunes t-shirts, and (for some) tagging. Tagging was a form of graffiti in which young people would sort of emulate the more hardcore gang graffiti by writing their “tagger” names on public property. I never participated in tagging, probably because I couldn’t come up with a cool tagger name and because I was just generally not one of the “cool kids.” I was more of a nerd. Still am.

Granted, there were definitely actual gangs in Fullerton in the early 1990s (most notably Fullerton Tokers Town and Baker Street), but the tagging trend was popular among lots of wannabes as well.

Anyway, this proliferation of graffiti prompted outraged and angry community meetings.

All of this outrage prompted the City Council to pass an “urgent” anti-graffiti ordinance with stiffer penalties than had previously existed, like 6 months in jail and/or $1,000 fine. The new ordinance made it unlawful for anyone under 18 to have in their possession a “graffiti implement” while on public or private property, unless it was school-required.

In 1993, a new Police Chief took the reins named Pat McKinley.

McKinley was a 29-year veteran of LAPD who joined the force just in time for the 1965 Watts Riots and took his new position just after the 1992 LA Riots.

Legally Forced to Act, Fullerton Takes Hopeful Steps Toward Affordable Housing

As my recent posts have chronicled, throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Fullerton City Council was very reluctant to fund or even approve affordable housing projects in town, even though the City received federal housing dollars and was required to set aside a certain percentage of property tax for this purpose.

The reasons for this reluctance (or outright refusal) were twofold: 1.) Some city councilmembers were ideologically opposed to using government funds for housing (preferring instead to subsidize things like shopping centers and sports complexes) and 2.) Angry neighbors showed up to council meetings to speak against low income housing projects in their neighborhoods, fearing it would bring all sorts of problems.

Like the City, the Fullerton School District was having budget issues and proposed to fill this gap by selling off surplus properties to affordable housing developers.

Some comments from concerned neighbors:

“Affordable housing is not the School District’s responsibility, but the City’s.”

“Why does it have to be in the backyard of our schools?”

“We don’t need any more low income housing in this corner of Fullerton.”

The City’s lack of affordable housing eventually prompted a lawsuit brought by two citizens that resulted in a settlement requiring the city to develop an affordable housing plan and allocate money for its implementation.

A newly created Affordable Housing Committee recommended spending about $3.5 million in federal and local funds for three affordable housing projects. Whether these projects would actually get built is another question. Stay tuned.

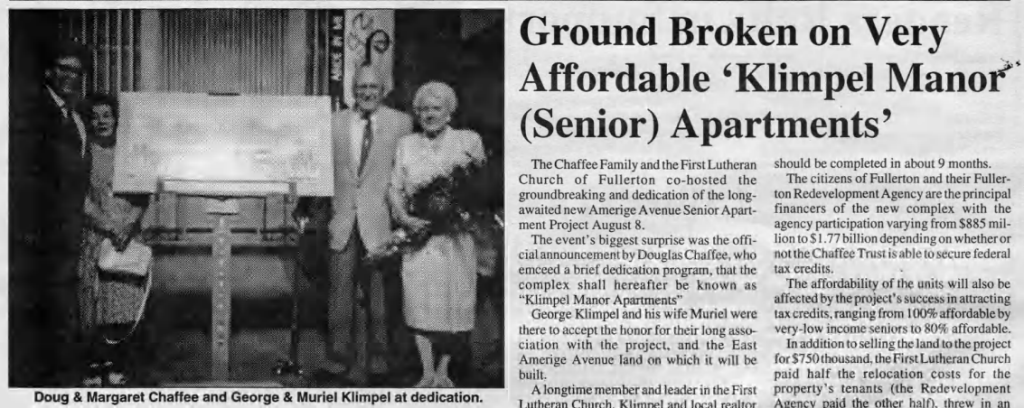

Additionally, a new affordable housing project for seniors, called Klimpel Manor, partly owned by the Chaffee family, and mostly financed by the City, was actually being built.

Housing discrimination was, unfortunately, still a thing in 1993.

Several plaintiffs, including the Fair Housing Council of Orange County, filed a class action housing discrimination lawsuit against the owners of 4 Orange County apartment complexes, including one in Fullerton.

“The lawsuit follows a lengthy period of investigation in response to ongoing allegations of housing discrimination against families and African Americans, the most frequent types of complaints filed with the Council,” the Observer reported. “It also alleges that family and African American applicants for housing were discriminated against by refusing to rent to them or steering them toward more ‘suitable’ housing.”

The apartment complexes listed in the complaint included the Fullerton Palms.

Homelessness

An obvious result of a lack of affordable housing was homelessness. To meet (some of) this need, the New Vista family shelter opened in 1986, helping seven families at a time with transitional housing.

How Fullerton Spent (Some of) its Redevelopment Dollars

The City of Fullerton had spent millions of redevelopment dollars to build a sports complex at CSUF, partially for the college’s football team. And then, CSUF dropped football.

The City also helped finance Knowlwood Restaurant (now Crawfish Cave) on the site of the former Melody Inn, a 100-year old building that burned down in 1989.

“Altogether, the net cost to the city of the two phases of development [Knowlwood and another building at the corner of Harbor and Commonwealth] will amount to $510,365,” the Observer reported.

Bicycle Users Get a Break

Fullerton (and Southern California in general) was a very car-centric place in the 1990s. Bicycle users sought to make the place more bike-friendly, first by establishing a Bicycle Users Subcommittee, and then by creating a bicycle master plan for the city.

The plan sought to include 20.7 miles of Class I (off-road) bicycle routes, 40.2 miles of class II (on-road, signed and striped) routes, and 16.5 miles of Class III (signed only) routes.

Dr. Vince Buck, longtime member of the Bicycle Users Subcommittee, “argued strongly for approving the full plan so that Fullerton would have a chance of increasing its number of bicycle-commuters from an estimated 1-2% of the work force to an achievable objective of 10-12%. Such an increase would make a substantial contribution to clean air in this area, he indicated.”

Unfortunately, the Planning Commission voted against the plan.

“It took a year for the Bicycle Users Subcommittee of the city Transportation and Circulation Commission to come up with recommended commuter bike routes through Fullerton, but only three hours for the Planning Commission to agree 6-1 that bicycles don’t belong in Fullerton’s future,” the Observer reported.

Assistant city engineer Don Hoppe…stressed that “there is no funding available to implement any of these routes, and the Bicycle Users Subcommittee does not have a priority list.”

“Southern California is a motorized world. The [State] Vehicle Code has done a pretty good job integrating pedestrians, bicycles, motorcycles and cars,” he said.

But then, hope was rekindled as City Council approved the proposed plan after many people showed up to advocate on its behalf. Whether the city would actually implement the plan was another question.

In other transportation news, the plan to redevelop the Fullerton Train Station was going off the rails.

Educational Inequality and Student Protests

Meanwhile, plans were rolling along to re-open Maple Elementary School, which had been closed in 1972 for being a de facto segregated school.

The plan was to open one grade per year until it was a fully-functioning K-6 school again. The City was spending $500,000 in redevelopment funds to refurbish the old school, built in 1924.

Maple had become segregated as a direct result of historic housing discrimination and segregation, which for decades kept Mexicans and African Americans south of the tracks. Even though, by 1990, overt housing discrimination was illegal, it still existed (see above story about the class action lawsuit) and it left a legacy of a city divided along ethnic/economic lines.

This legacy perpetuated itself in all kinds of ways, including school attendance boundaries. The School Board approved an attendance boundary change which sent Valencia Park elementary school grads to Nicolas Junior High (south of the tracks) and Fern Drive grads to Parks Junior High (north of the tracks).

One board member expressed reservations about the decision “to send the 6th graders to the junior high school nearest to their homes, while further concentrating poorer and ethnic minority children at the lower scoring Nicolas Junior High School.”

The Fullerton Elementary Teachers Association (FETA) was against boundary change.

“According to recent studies, heterogeneous grouping of students including ability, academic achievements, parental support and involvement, and ethnicity has been the most successful in ensuring the greatest academic growth in all students,” a FETA statement read. “In this time more than ever before, people must open their eyes and begin to bridge the differences between us. Decisions like this beget divisiveness and lack of understanding o f each other. We implore you to make your decision based upon the long term benefits for all children.”

Another way this historic inequality perpetuated itself was the ability of higher income parents to give gifts and donations to their kids’ schools.

“We don’t like to say no to gifts, but we also don’t like to exacerbate inequities in educational opportunities between the schools,” commented Trustee Elena Reyes Jones.

“…it is the policy of the Board of Trustees to discourage all gifts which may directly or indirectly impair the Board of Trustees’ commitment to providing equal educational opportunities to the students of the District.”

Meanwhile, local high school and college students took to the streets on September 16 (Mexican Independence Day) for a march organized by the student ground MEChA seeking: 1) A Chicano Studies Major, 2) 50% hiring floor for people of color, 3) More emphasis on all ethnic and gender studies, 4) More ESL classes, and 5) No ethnic group be excluded from challenging a class.

Around 300 college and local high school students marched down Chapman Avenue to Harbor Blvd., where they met with Fullerton police, who at first attempted to block them, but then chose to block traffic, allowing the march to continue down Harbor.

Police again confronted the marchers at Valencia and Harbor, where “the students broke ranks and ran through and around the police cordon and through the Price Club parking lot onto Lemon Street, where they headed back toward the FC campus.”

The students and police again clashed at the Lemon underpass, which is adorned with Chicano murals. When students refused to be blocked, violence broke out. Officers used pepper spray and batons on uncooperative protesters.

Four adults and two juveniles were arrested.

After the march, when asked if the college would accede to the students’ demands, Richard DeVecchio, vice president of student development and services, said, “We will not be intimidated. More meetings and fewer demonstrations would be fruitful.”

Students also protested tuition hikes at Fullerton College.

Of Toxic Waste and Endangered Birds

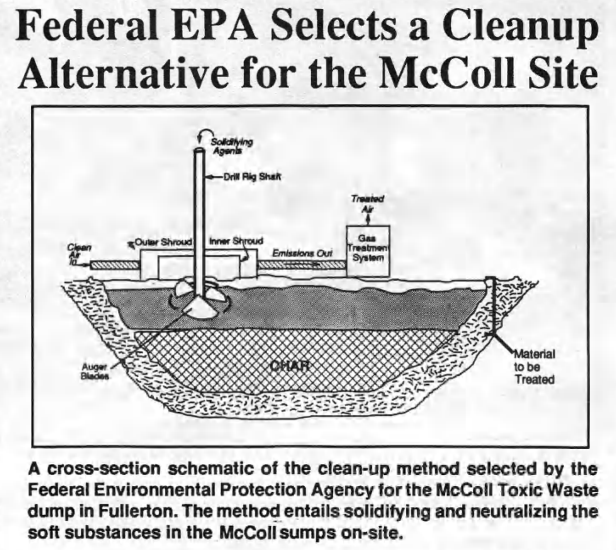

In the ongoing saga of the McColl toxic waste dump in northwest Fullerton, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finally, after years of study and delays, chose a plan to deal with the waste.

Ultimately, they chose not to remove or destroy the over 200,000 tons of waste, as originally planned. Instead, the solution was basically to solidify some of the oil waste, build walls around it, cap it, and then monitor forever to see whether it was leeching into the groundwater (it was).

This was the solution the oil companies responsible for the waste had been lobbying for.

Today, the McColl site is part of the Los Coyotes golf course. Driving by, you would have no idea it’s there.

In other environmental protection news, United States Fish and Wildlife Service listed the California gnatcatcher (bird) as a “threatened” species due to development in Southern California of its natural habitat, coastal sage scrub.

Upon hearing this announcement, the Unocal company, which planned to develop east Coyote hills with housing and a golf course began studying and monitoring gnatcatchers on about 110 acres of their land and developed a Habitat Conservation Plan.

Chevron, which owned west Coyote Hills, took a different approach: “Chevron’s response was to destroy about 100 acres of the rare habitat, just prior to the March announcement by Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt that the Gnatcatcher had been officially listed as endangered.”

Culture and Community

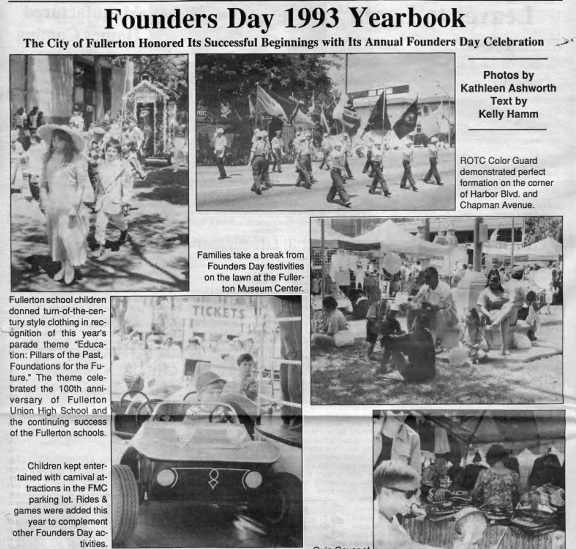

Community and cultural events included the First Night (New Years) Celebration, the Downtown Market, A Night in Fullerton, and the annual Founder’s Day Parade.

“The market creates a sense of community. It provides a weekly destination for people to meet and promotes Fullerton for those outside the area,” said Ann Mottola, Special Events Coordinator for the city. Local vendors, farmers and artists gather near the Fullerton Museum Center to sell their goods and interact with patrons.

“The local arts community joined talents recently to present a free night of dance, music, drama, and art during the 29th annual A Night in Fullerton,” the Observer reported. “Nearly 30,000 persons traveled to 14 locations throughout the city to survey an eclectic evening of performances ranging from barbershop quartets to water-color demonstrations to classical and contemporary ballet.”

Deaths

Leon (Jack) Owens, a longtime resident of Fullerton, died of a heart attack at age 60. The Owens are a prominent family in Fullerton, with roots stretching back decades. In honor of Leon, his family established the Leon Owens Foundation, whose purpose is to provide scholarships for needy FUHS and Fullerton College students.

Duane Winters, who served on Fullerton City Council for 28 years, beginning in 1956, died at age 85 of natural causes. The baseball field at Amerige Park is now known as Duane Winters Field.

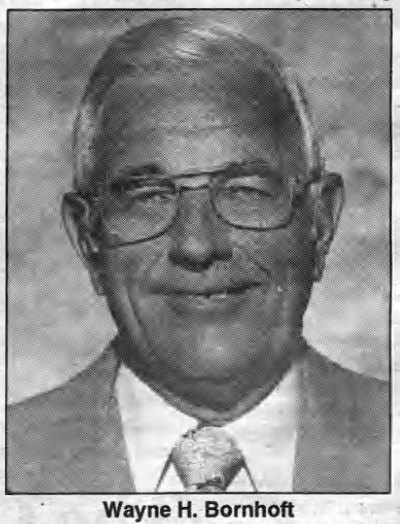

Wayne H. Bomhoft, retired chief of the Fullerton Police Department and former Mayor of the City of Fullerton, died of cancer at age 76. In 1957, Bomhoft was hired as chief of the Fullerton Police Department, replacing Ernest Gamer. Following his retirement from the police department in 1977, he won a seat on the Fullerton City Council in 1978, and served as mayor in 1980 and 1981.

Bill Calhoun, who ran a shoe shine stand on South Malden for 22 years, died of cancer at age 62. According to the Observer, “The stand had become a familiar site to all manner of clientele and passers-by since 1970, when Bill took over the small Malden Avenue stand from a Mr. Haywood Holden.”

Stay tuned for headlines from 1994.