The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

The Fullerton Observer newspaper was formed in 1978 by Ralph and Natalie Kennedy and friends to provide a more progressive counterbalance to the more conservative Fullerton News-Tribune and Orange County Register. The Fullerton Public Library has digital archives of the Observer stretching back to 1979. Here are some top news stories from 1988.

What to do with 10,000 Truckloads of Toxic Waste?: The McColl Dump Site

The state Department of Health Services and the Federal Environmental Protection Agency gave a presentation to local residents and leaders about an interim plan to deal with the toxic materials at the McColl dump site (Fullerton’s first Superfund site), including a gas collection and treatment system, a special gas-and-liquid-impervious plastic liner, and a soil cover.

The oil companies had submitted a proposal to construct a $12.5 million containment system including a cap, as both an interim treatment and a final solution. This was rejected by the EPA as an interim action, but was under consideration as a permanent remedy.

The Observer ran a three-part series on the history of the McColl dump site.

Between the years 1942 and 1946, oil refinery waste was dumped on a section of the old Emery Ranch in northwest Fullerton, owned by Eli S. McColl. The toxic waste contained sulfuric acid, benzene, hydrogen polymers, nitrogen salts and sulfonic acid. Twelve dump pits (or sumps) ranged in size from 8-30 feet deep and 100-350 feet across.

The amount of waste and contaminated soil at the dump site is around 200,000 cubic yards, or enough to fill 81 olympic-sized swimming pools.

In 1951 McColl covered some of the sumps with drilling mud, mainly to reduce the foul odors. Until the mid 1960s, the site became a place of general dumping of trash and debris.

In the 1960s, The Los Coyotes Country Club covered some of the sumps to develop a golf course.

The first housing development next to the dump site opened in 1968. By 1980 residential development surrounded the site. Toxic waste notwithstanding, this was prime real estate.

However, by the late 1970s, residents began to complain of headaches, eye irritations, and breathing problems. This prompted the California Department of Health Services (DHS) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to study the site in collaboration with a number of oil companies who were potentially liable for the dumping.

The saga of the McColl dump site corresponds in interesting ways with the rise of environmental protection in the United States. The EPA is a relatively recent phenomenon in American history, created in 1970. The Superfund program to deal with large contaminated sites got started in 1980.

By 1982, over 70 hazardous waste dumps were identified within California, and the McColl site was at the top of the list due to its high potential cleanup costs and impact on public health.

The newly-created Superfund program (created under liberal, environmentally conscious Jimmy Carter) faced numerous political and legal hurdles under the presidency of conservative Ronald Reagan, who preferred to cut, rather than increase, government regulatory agencies. The agency also sometimes came into conflict or disagreement with California’s DHS, not to mention litigation from the responsible parties themselves, the oil companies, who wanted to limit their liability.

The result of all this was delay after delay in what to do to clean up the site. However, by 1984, all parties had reached a tentative agreement to remove the toxic materials elsewhere. But where?

Two lucky locales were chosen to receive our muck–the Casmalia Resources facility in Santa Barbara County and the Petroleum Waste Inc. facility near Buttonwillow in Kern County. It was to be the largest toxic cleanup program in California’s history.

However, when Santa Barbarans got word of the plan to bring 10,000 truckloads of toxic waste into their fair county, they (understandably) were not happy.

In 1985, the City and County of Santa Barbara filed suit to block the transportation of McColl waste. Kern County followed suit.

More and more delays.

In 1981, 141 families filed suit against the City of Fullerton, the development companies that built their neighborhoods, and six oil companies, claiming that the developers and the City knew of the site dangers. The oil companies involved include Shell, ARCO, Texaco, Unocal, Phillips Petroleum, Chevron, and McAuley Oil.

The oil companies, developers, and the City ended up settling with the majority of neighbors, paying out a combined $12 million. Interestingly, the judge chosen to oversee settlement payments was Joseph Wapner of “People’s Court” Fame.

Meanwhile, as state and federal agencies figured out what to do with the toxic waste, local neighbors formed a group called the McColl Dump Community Action Group (MAC), with about 100 members.

Aside from health concerns, the neighbors were concerned about the impact of a Superfund site on their property values.

As delays continued, MAC co-chairperson Betty Porras said, “10 years is long enough. We were promised a cleanup—not a coverup!”

The lawsuits by Santa Barbara and Kern counties prompted the need to create an Environmental Impact Report, which led to more delays.

By 1988, the EIR was postponed. Stay tuned for more on the McColl saga.

An article entitled “Little Known Facts on Toxic Waste in Fullerton and Orange County” put the McColl situation in perspective.

In 1986, Fullerton generated 4,269 tons of hazardous waste. Anaheim, though, was much worse, with 39,677 tons, according to state and county data.

“Fullerton’s McColl dump is one of 10 so-called ‘Superfund Sites’ in Orange County, although its estimated 200,000 tons of hazardous waste is again dwarfed by the amounts present in county 3 military installations: 2,500,000 tons at the El Toro Marine Corps Air Station, 1,250,000 tons at the Seal Beach Naval Weapons Station, and 625,000 tons at the Tustin Marine Corps Air Station in Tustin.”

The top two generators of Toxic Waste in Fullerton were the Kimberly-Clark Corporation (1061 tons) and Hughes Aircraft Co. (806 tons).

Local Politics

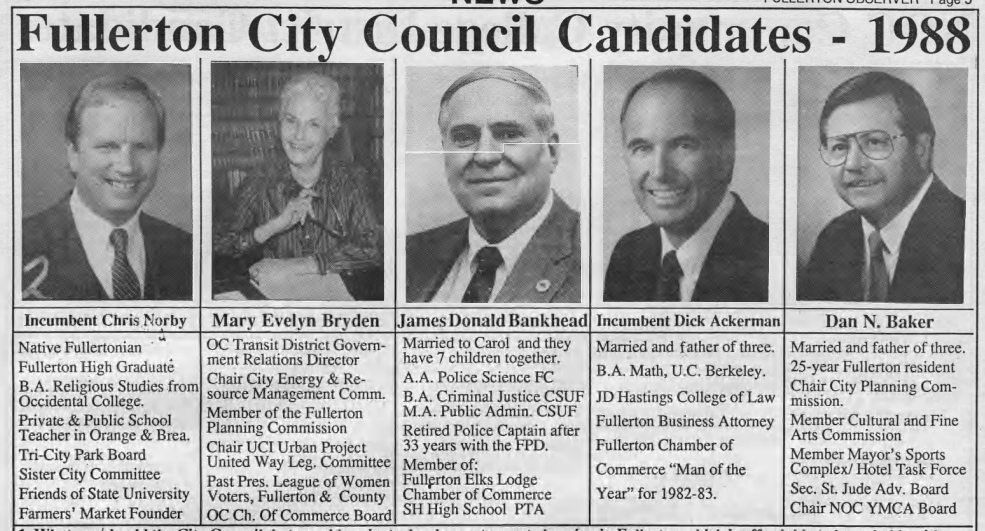

1988 was an election year. Below are the candidates who ran for City Council.

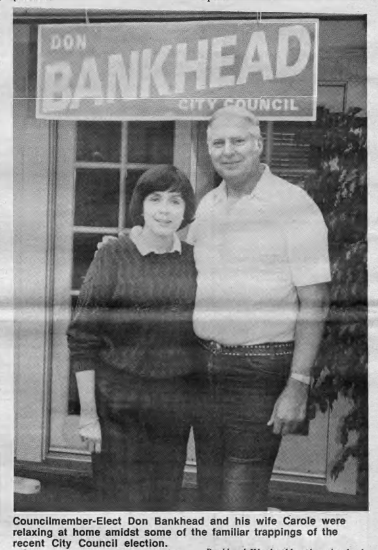

Incumbents Chris Norby and Dick Ackerman were re-elected along with newcomer Don Bankhead, a former police captain.

Here is the annual budget, which the council approved.

Housing

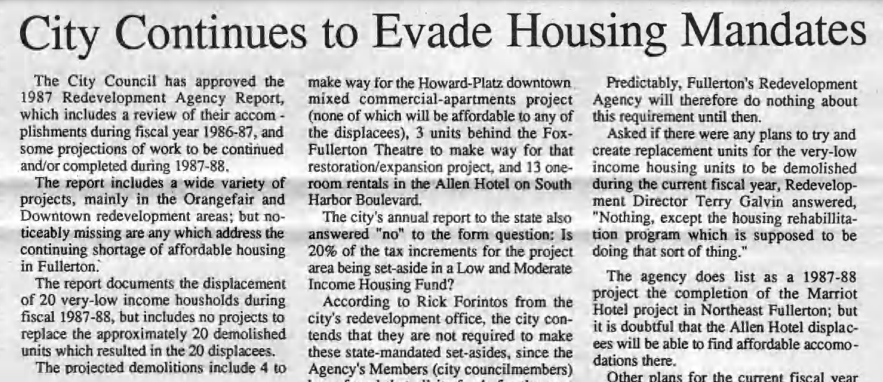

The conservative council majority continued to refuse to use redevelopment funds for affordable housing, despite (unenforceable) state mandates that it do so.

California cities are required to produce a Housing Element as part of the general plan. An Observer article describes how the City regularly refused to comply with the state’s recommendations, particularly those regarding affordable housing.

The Observer asked each Councilmember give their view of the City of Fullerton’s responsibility in the area of housing. All but Molly McClanahan (and, sort of, Buck Catlin) were ideologically opposed to using government funds for affordable housing. They preferred to let the “free market” somehow handle things, while using redevelopment funds to subsidize private market rate developments (see below).

Richard Ackerman: “I do not favor such measures as subsidized housing or inclusionary zoning, which overly impact the free market system. Government should not be directly involved, except through their adoption of a General Plan, which designates their best ideas for land uses and densities based on topography, and the expedition of building processes, charging fees which are commensurate with the costs of the services provided.”

Chris Norby: “We should allow the private sector to build needed housing with as few restrictions as possible. I do not favor the use of any city funds for housing.”

Buck Catlin: “I think the City should be involved in providing housing for the people who are employed here, especially the industries that support us, and especially for the middle management people in those industries.”

Linda LeQuire: “I think the City should promote a variety of housing types, but I have never favored government for housing, except for seniors…There is enough employment for anyone who wants to work and have a good standard of living. Temporary help may be needed in some cases, but this is not the responsibility of local government.”

Molly McClanahan: “While Fullerton has done much to preserve our older housing stock through low interest loans, there is a need for more affordable housing. Opportunities exist for the public and private sectors to work cooperatively; county funds are available to be leveraged with private development money. I support using some redevelopment monies for housing.”

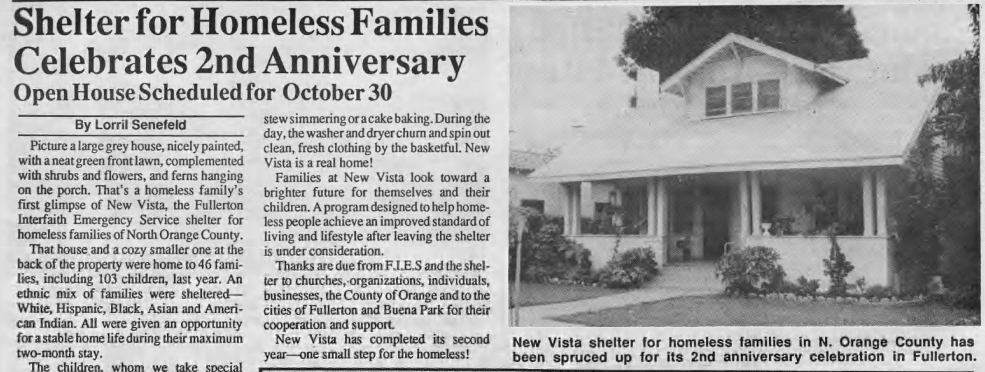

Homelessness

Meanwhile, local nonprofit Fullerton Interfaith Emergency Services (now called Pathways of Hope) was doing its part by running the town’s only homeless shelter.

Education

In 1978, California voters passed Proposition 13, which severely capped property tax increases, thus limiting local funding for things like education.

A report entitled “Proposition 13, Ten Years Later” assessed the impact of Proposition 13 has had on all levels of California government.

“The report confirmed that the primary impact of Prop. 13 on school governments has been an erosion of local control, as larger and larger percentages of the total school funding has shifted to the state,” the Observer stated. “Statewide, districts received 42% of their funding from the State prior to Prop. 13. Since 1978, this number has increased to 85 to 90%. This has put school districts at the mercy of the Legislature and the Administration, regardless of their community’s desire to supplement the funds available for public schools…Schools have been forced to resort to such tactics as swap meets and bingo games to fund programs which are not specifically provided for by the State funding.”

Statistics released by the district showed that Richman and Woodcrest schools had 79.4% and 63.4% minority students respectively, making them de facto segregated schools, while Rolling Hills school had only 18%.

While in the 1960s and 1970s, this prompted the district to take corrective action, by the 1980s, there was little political will to do anything about de facto segregated schools.

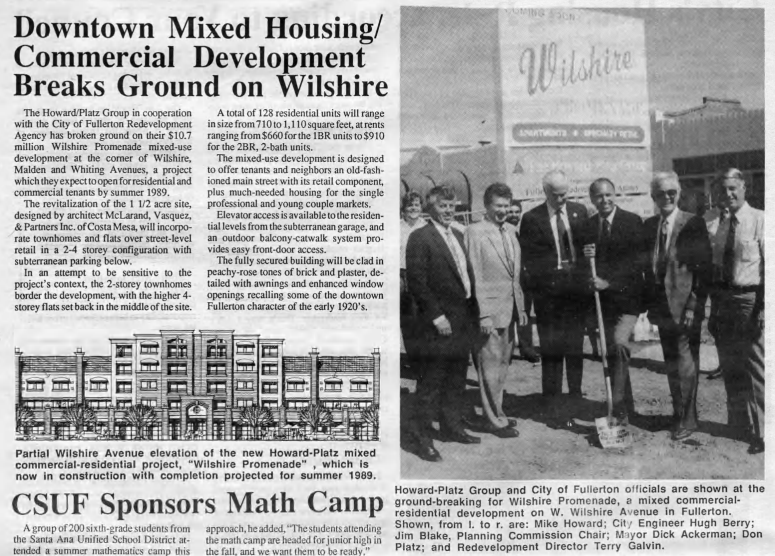

Development/Redevelopment

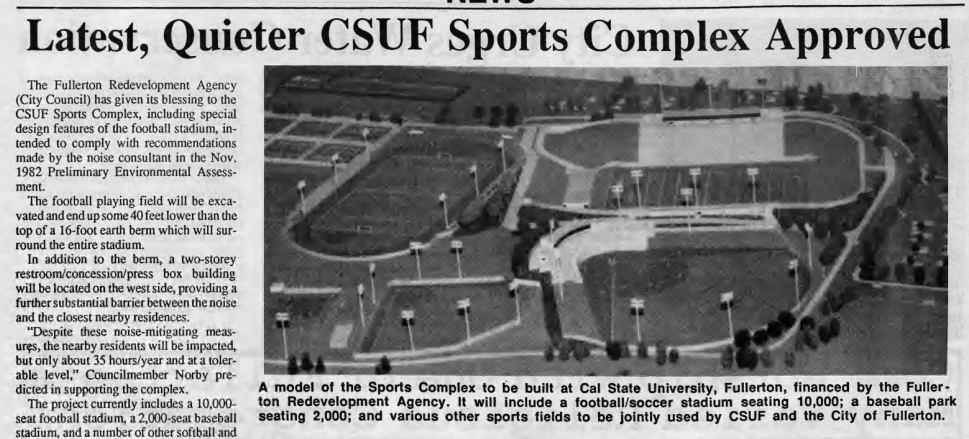

While City Council refused to use its significant Redevelopment funds to subsidize affordable housing on the philosophical grounds that it didn’t want to interfere with the free market, Council preferred to use those funds to interfere in other markets by subsidizing things like market-rate housing, parking structures, and a Sports Complex, as the clippings below illustrate.

The Fullerton Redevelopment Agency (City Council) approved funding for the CSUF Sports Complex, which included a 10,000- seat football stadium, a 2,000-seat baseball stadium, and a number of other softball and multi-purpose fields plus the lighting for all these fields.

Racism/Bigotry

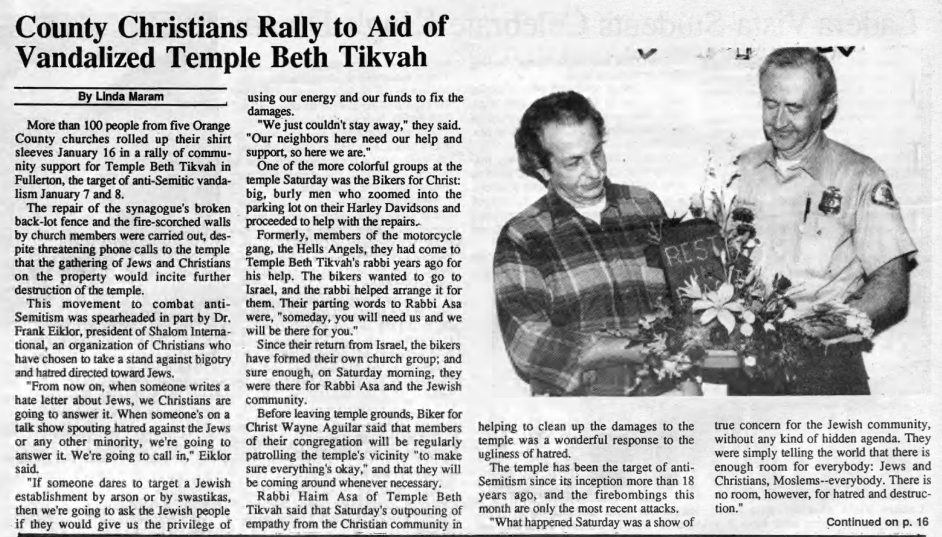

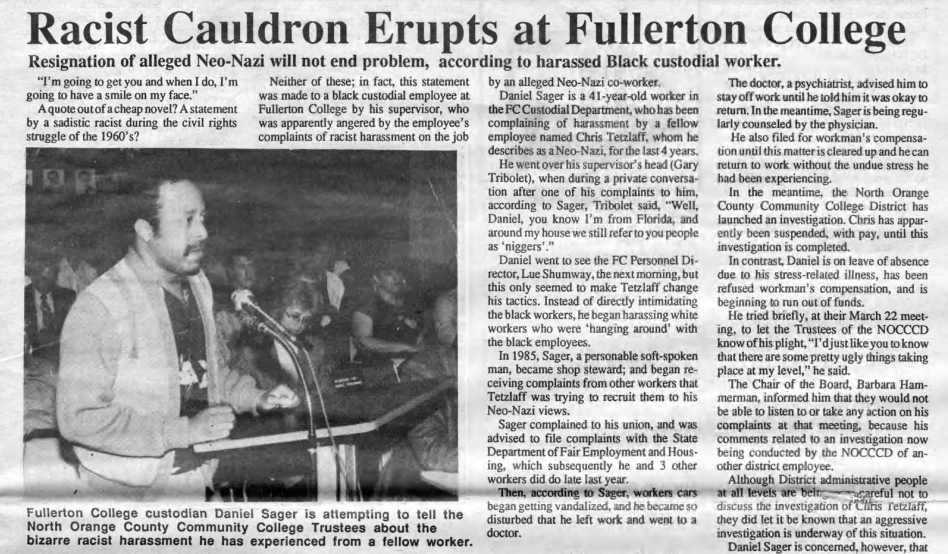

Unfortunately, a number of incidents of racism/bigotry were documented in 1988.

Stickers from the hate group White Aryan Race (WAR) were found stuck on lampposts outside the Thrifty Drug store in Yorba Linda.

“According to their area coordinator, Eric Thompson, the White Aryan Resistance is an umbrella group for many like-minded groups, such as the National Socialist Party, Identity Christians, Klu Klux Klan, etc,” the Observer wrote.

Thompson said, “We are willing to die for future generations of white children. We feel obligated to nature to keep our racial/cultural strain pure and uncontaminated.”

Culture

The Chapman family, as the Muckenthalers had done before them, wanted to donate their ranch house for public use of some kind.

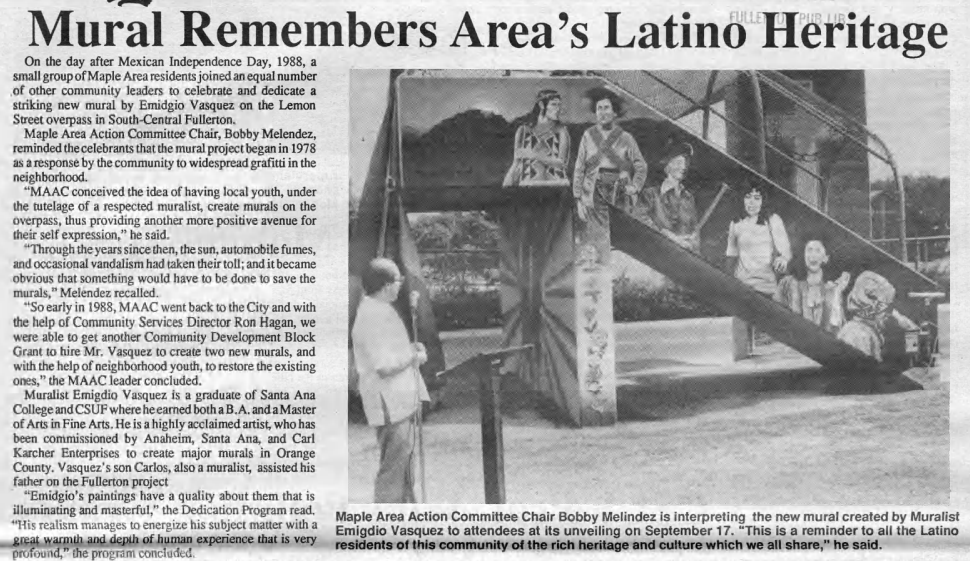

Local Chicano muralist Emigdio Vasquez painted a new mural on the Lemon underpass, facing Maple School. The other Lemon murals had been painted in 1978 as a response by the community to widespread grafitti in the neighborhood. Local youths helped to paint the murals.

Vasquez painted numerous murals around Orange County, mostly representing the Latino community.

The new mural depicts “the Latino woman from her Aztec roots in Mexico, through her role as a soldier in the war for Mexican Independence, as ‘Rosita the Riveter’ in World War II, to her role as “La Chicana” in the 1960’s, in her emerging modem position as a professional who can have a family and a career outside the home,” the Observer stated.

The City held its annual Founder’s Day Parade.

In 1988, “The Purple People Eater” (featuring Little Richard) was filmed in Fullerton by Sunny Hills alumna Linda Shayne.

Facing opposition from residents, city council denied a permit for a burlesque/cabaret theater.

Health Care

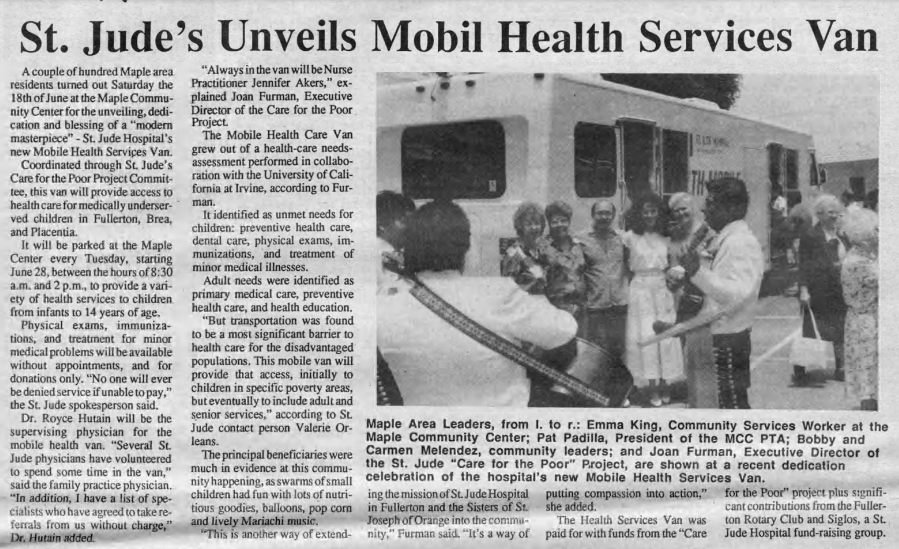

To assist with health care for lower income residents in south Fullerton, St. Jude unveiled a Mobile Health Services Van.

AIDS was a big concern in 1988.

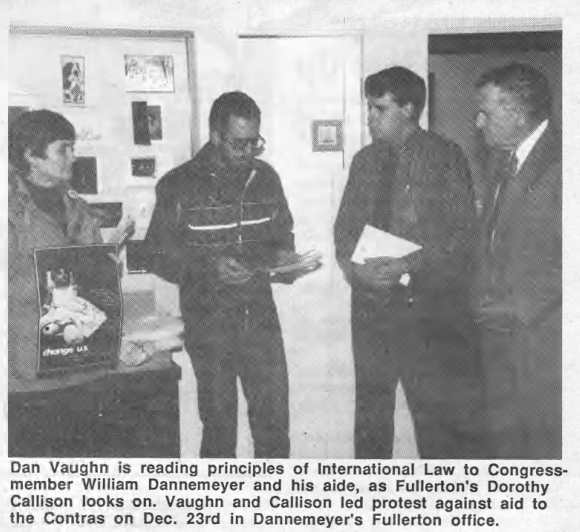

National/International Issues

National and International issues included the US involvement in Central America and Apartheid in South Africa.

Immigration

In 1988, the Republican position on illegal immigration was very different than it is today, so much so that, following the lead of Ronald Reagan, the City Council (with four out of five members being Republicans) issued an Amnesty proclamation.

Transportation

The Observer continued its crusade for better public transit and bicycle infrastructure–for environmental and health reasons.

Drugs

Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” solution to underage drug use was very popular and largely ineffective.

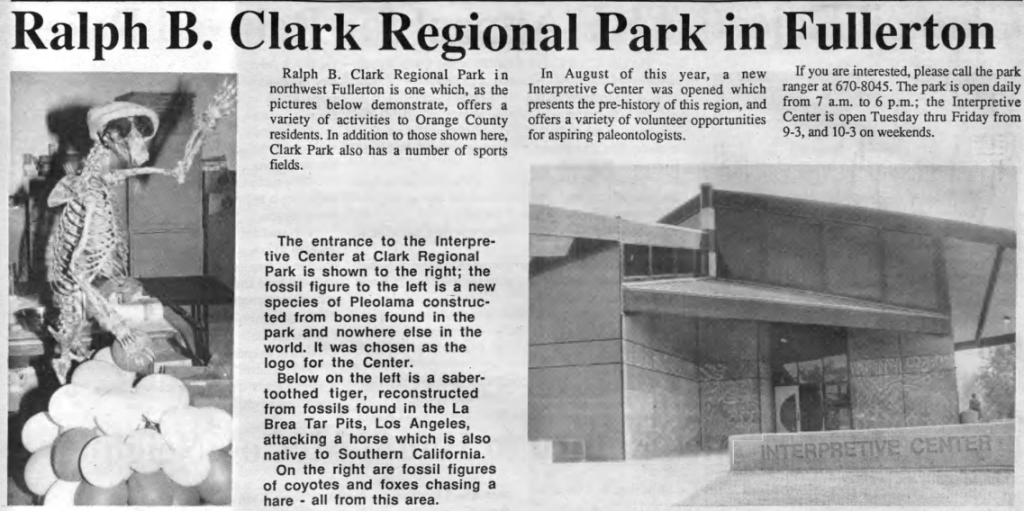

Fullerton Prehistory

A new little paleontological museum opened in Ralph B. Clark Regional Park, which features fossils and bones excavated when the park was created–showing evidence of Fullerton’s prehistory. These artifacts included, for example, evidence of ice age creatures like mastodons, sabre-toothed cats, and giant sloths.

Deaths

Prominent local lawyer and citizen Walter Chaffee died. After serving in World War II, Chaffee opened a law practice in Fullerton, partnering with former city attorney Albert Launer. In 1952, Chaffee served as the City Attorney. In 1956, Governor Pat Brown appointed Chaffee to served as a judge at the North Orange County Municipal Court.

In a predominantly Republican area, Chaffee was an active Democrat, serving as chair of the Orange County Democratic Central Committee in 1962.

“It was during this period when he made one of his most important contributions to Fullerton and surrounding communities. During the 50s, the John Birch Society and the Christian Anti-Communist Crusade were becoming very active in North Orange County. Most people were intimidated by their aggressive and accusatory campaigns and rhetoric,” the Observer states. “Walt and a small group of likeminded patriots publicly challenged these demigods, and were successful in preventing their attempts to take over the local Fullerton school boards. At one point, according to Walt’s longtime friend Don Butka, the John Birch Society sued Chaffee for $1 million for things the so-called ‘secret six,’ as Walt and his protectors of the constitution were dubbed by the Santa Ana Register, had said about their extremist adversaries. As Butka remembers it, however, the suit was dismissed by the judge when the defendants produced a variety of information to prove true the statements they were accused of having fabricated.”

Chaffee also helped organize the North Orange County Hospital Building Association, which was instrumental in securing the site and promoting the hospital now known as St. Jude.

Chaffee’s son is former Fullerton Councilmemer and current OC Supervisor Doug Chaffee.