The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

W. Ray Easton was Interviewed in 1974 by Vivien Allen for the CSUF Oral History Program. Here are some things I learned from his interview.

He was born in 1898 in San Bernardino County. At age 14 he started working in citrus packinghouses.

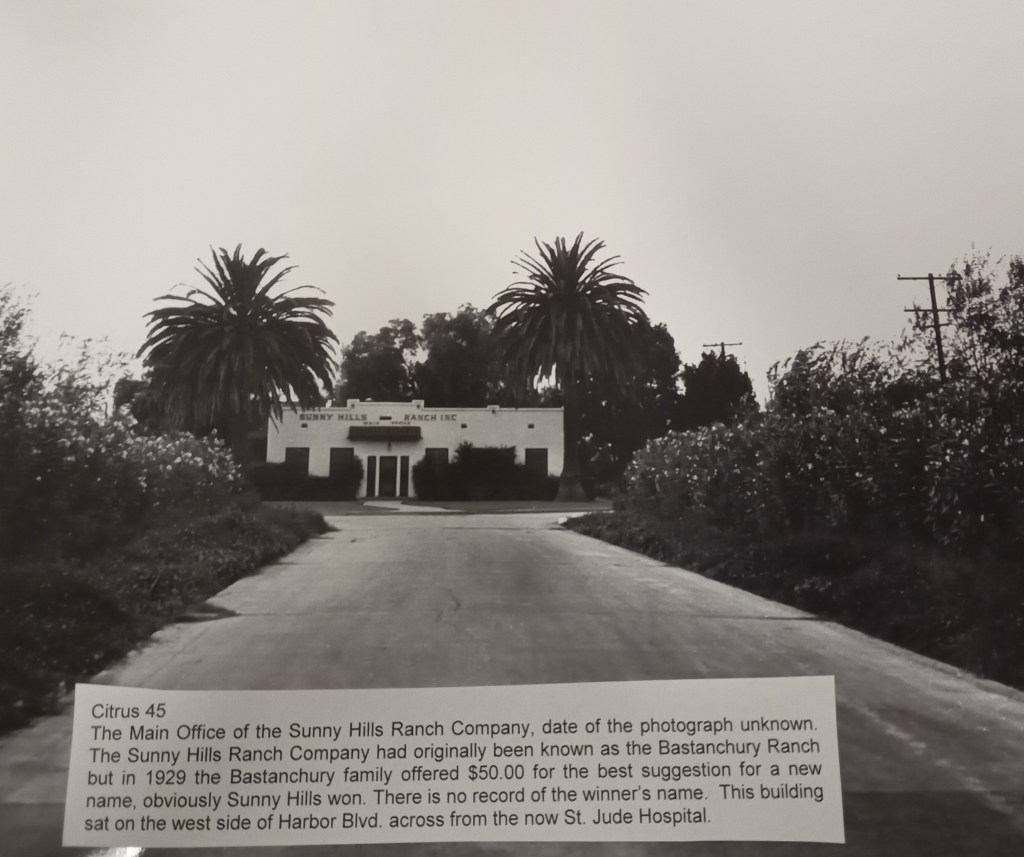

He eventually went to work on the Bastanchury Ranch in the 1920s, which was owned and operated by the Bastanchury family, Gaston Bastanchury being the principal operator.

The 1920s were an era of very large expansion of orange groves, with the Bastanchury Ranch being a prime example of this.

“I became manager of the packinghouse operations, which had [expanded] into three citrus packinghouses in addition to a tomato packing plant,” Easton said. “This ranch extended an additional 4,000 acres or so [beyond its original 2,500 acres] from leases and the like all the way from Buena Park to Olinda, surrounding Brea and also mostly surrounding Fullerton.”

The Bastanchury Ranch had their own railroad spur lines.

Then came the Great Depression, which proved disastrous for the Bastanchurys. “They had to borrow some money from bond holders, and there was a foreclosure procedure pending, but they did close out the Bastanchury ownership, and at a later date the properties were broken up into subdivisions. Today there are many, many homes and businesses on the original ranch,” Easton said.

Easton left the Bastanchury Ranch in 1931 to manage a citrus packinghouse in El Cajon for one year only. Then in 1932, he took a job managing the Bradford Packinghouses in Placentia.

“There was an enjoyable experience of competition between Placentia Mutual, Bradford Brothers, Placenta Orange Growers Association, Eadington Fruit Company, and many of the local packinghouses,” he said.

Easton discussed Sunkist, the large citrus marketing organization.

“It offers a real good sales opportunity with a very reliable organization which started back in the 1800s as the Californa Fruit Growers Exchange and later became Sunkist organization,” Easton said. “Monthly meetings were held between the packinghouses with speakers from Sunkist getting out into the country and showing the growers that Sunkist has their interests mainly in consideration…Orange County as a whole was very heavily Sunkist.”

The advantages of selling with Sunkist was that they had connections with eastern buyers and were a reliable brand.

In the winter, there were navel oranges and lemons. Valencia oranges came in the summer.

Packinghouses took responsibility for harvesting and packing fruit for the grower.

“As the fruit is picked, mostly by Mexican labor, it is hauled to the packinghouse, currently by trucks but earlier by horse and wagon,” Easton said. “As it is delivered to the packinghouse it is weighed, or tabulated according to boxes, and the record of receipt is given to the grower showing that the delivery of every box is accounted for.”

Each packinghouse had its own label.

“In the Bradford Organization the main labels were California Dream or Tesoro as Sunkist, and the one in Bastanchury was Basque,” Easton said. “The grades were very closely looked at by Sunkist inspectors so every packinghouse had to conform to a set of rules that made a very uniform grade in all packinghouses. That kept Sunkist pretty well in front of all others, because they had standardized the quality.”

Thus, most packinghouses packed fruit from many growers’ groves. A few notable exceptions were C.C. Chapman and the Bastanchurys, who had their own packinghouses.

The Bastanchury packinghouse was located where the automobile club office is now on top of the hill [on Valencia Mesa drive near Harbor Blvd), and the packinghouses were just a little southwest of that.

He describes the delicate art of grading and packaging oranges: “The experienced packers were able to perform in a very excellent fashion. In the early days before cartons the fruit had to be wrapped with a thin tissue paper with some lithography work on it and printed withe brand names.”

Most of the pickers and packers were local to Orange County.

Easton describes the conditions that led to the decline of the orange industry: “There was a disease that developed known as tristeza or quick decline that was very injurious to trees…Many of the orchards were pulled out because of that disease, but the principle issue that caused the reduction of orchards was the cost of raising oranges on high priced land and a reduced level on citrus…You can only sell out to the subdividers, the apartment setups, shopping centers and things of that kind. Land just became too valuable to stay in the orange business.”

“As can be readily seen, the groves in northern Orange County have pretty well disappeared,” Easton said. “It is practically all factories, rooftops and homes, pavements and streets, very few orchards left in the whole of Orange County.”

Leave a comment