The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Dorothy Newton was interviewed by David L. Miller in 1970 for the CSUF Oral History Program. Here are some things I learned from her interview.

She was born in eastern Colorado, then moved to to Illinois, where her father was a minister at the Christian Church. She moved out to California for college, where she attended UCLA and USC. In 1934 she was hired to teach English at Fullerton Union High School. At that time there were around 800 students, and Fullerton was the only high school in the area. Students came to campus on buses from neighboring cities like La Habra and even Yorba Linda. It wasn’t until the post World War II population boom that other local high schools were built.

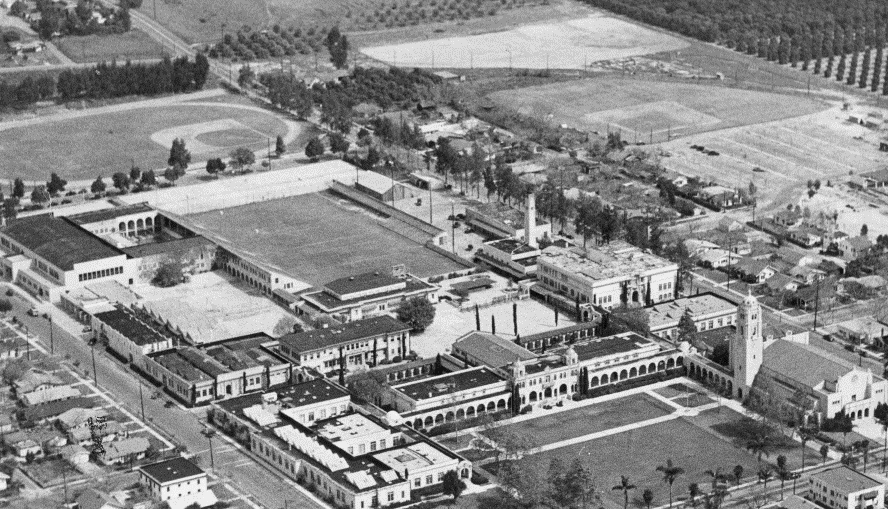

The only buildings that remained in 1970 from when she arrived in 1934 were the auditorium and the gym. All the rest of the buildings had been replaced. These included the original English building, mathematics building, library, administration building, science building, junior college building, industrial arts building, and the music and speech-arts building. These buildings were eventually torn down and replaced with larger, more modern ones, to accommodate a larger student body and to have buildings that are up to code. Since the Auditorium was built five years after the rest of the high school, it could be stated that none of the original buildings of the high school still stand.

Lest we get too sentimental about this, it should be remembered that the current Fullerton High school is actually the third iteration. The first was torn down, and the second burned down.

When Newton arrived, the junior college and the high school were on the same campus and were under the same Board of Trustees. The division then began when the junior college bought the property across the street and began to build their own buildings.

When she first arrived at FUHS, Newton recalls, “we had a rigid dress code and it, of course, affected the girls more than the fellows. The girls were required to wear midis and dark blue or black skirts and the only difference in their appearance was the color of their ties. Freshman, of course had to wear green ties, sophomores wore red ties, the juniors wore blue, and the seniors wore black ties. That’s what they wore and that was the requirement so far as clothes were concerned. The first break in that was when they finally declared Wednesday as ‘civilian day’ and they could wear a school dress on Wednesday. Little by little, you can see dress codes have disappeared from the scene.”

In addition to teaching English, Newton taught drama (including play production), and speech.

She remembers that, at times, students were placed into levels of English based on ability, and other times they were placed in classes with multiple ability levels mixed–depending on the prevailing teaching philosophy of the time.

As time passed, new classes were added, such as economics and auto mechanics, while others were taken away, such as printing and foundry. Others were modified to reflect changing times, such as home economics.

“Every department has adjusted according to the changing of pattern and requirements of the time,” she said.

In the English department, “They [students] have a much wider choice of whether they want to pursue science fiction, classical background, British literature, United States literature, Biblical literature, or whatever,” Newton said. “They have modernized the study of mass media in the line of types of mass media that we’re living with today.”

Because Fullerton used to be an agricultural area, Newton remembers that “in the beginning of the school year, a number of youngsters who worked in the fields would be two or three weeks late in entering because either their families, or perhaps the older youngsters themselves, were itinerant farm workers. This is no longer a part of the pattern of our life.”

Speaking of agriculture, FUHS has long had a strong agriculture program. This program still exists, long after agriculture has gone from the surrounding area.

Newton remembers the shock of the U.S. being attacked at Pearl Harbor and entering World War II.

“That was one of the most traumatic experiences for us, and the school, too,” Newton said. “The uncertainties of what lay ahead…the youngsters were just as disturbed and very, very realistic because many of them did enlist as soon as they could.”

Newton herself also enlisted and was gone from campus from 1943-1946.

“I was part of the Women’s Reserve of the Navy and had the interesting experience of encountering a number of my own former students at the Naval Air Station at Alameda, California, where I was,” she recalls. “It was a far different experience during those years, that was true, and there is a bitter part to it, too. Those youngsters came to be very close friends and as word came back that some of them wouldn’t be returning, it was pretty hard to take.”

Because of young men (and some teachers) enlisting, the high school and junior college had lower enrollments during the war years.

After World War II, the area experienced rapid growth and more high schools were built–La Habra High School, Buena Park High School, then Sunny Hills High School.

When asked if she noticed any differences between the student of 1940 and the student of 1970, Newton replied, “I don’t think I can find any major differences; kids are kids, They went through the same processes, the same uncertainties and the same feelings of growing pains then that they do now. Matters of their entertainment and their free time changed with the patterns of life, but so far as the youngsters’ attitudes themselves, I don’t think there is a great difference.”

Leave a comment