The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Robert “Bob” Clark was an orange rancher who worked for the city of Fullerton to bring industry in the early 1950s. He later served on the board of the Orange County Water District. Bob was interviewed by B.E. Schmidt in 1970 and 1971 for the CSUF Oral History Program. Here are some things I learned from these interviews.

The Town of Orangethorpe

Bob Clark’s wife was Helen Olgar, who was from a pioneer family in the Orangethorpe District. The town of Orangethorpe, which no longer exists, was a 6.25 square mile area that encompasses parts of what is now south Fullerton, north Anaheim, and Buena Park.

Some of the first farmers in the area settled in Orangethorpe, even before the town of Fullerton was created.

In a 2018 article for the Fullerton Observer, Terry Galvin wrote, “Well into the 1950s, Orangethorpe consisted primarily of ranch homes surrounded by grove upon grove of orange, lemon, and walnut trees. Farmers and ranchers in Orangethorpe formed a tight- knit community, and many important Fullerton families—the Royers, Gardiners, Spencers, and Hiltschers— came from the Orangethorpe district. The most famous individual born in Orangethorpe was guitar legend Leo Fender (1909-1991), who attended the Orangethorpe School.”

The Olgar’s family farm was on Brookhurst and Orangethorpe. The town of Orangethorpe had their own school and district and Helen’s father served on the school board board.

According to Galvin, the residents of Orangethorpe voted to incorporate in 1921 as a city “in order to prevent being annexed by Fullerton and to stop a planned sewage farm from being built by Fullerton. In 1923, a sewer line running from Fullerton to the ocean was planned, ending the sewer farm threat, so on December 31, 1923, the residents of Orangethorpe voted to unincorporate. However, the sewer farm was ultimately implemented by Fullerton because the sewer line to the ocean was never built. The sewer farm was abandoned by 1926, and ultimately became the site of the Fullerton Municipal Airport in 1927.”

Bob’s father-in-law was a leading citizen who had organized the Orangethorpe School District and incorporation back in the 1920s to prevent the sewer farm from being placed near his property.

Bob and Helen met in Los Angeles and were married in Santa Barbara. For a while they lived in Los Angeles, and Bob worked as a “special effects man” for movies. Eventually, they moved back to Orangethorpe and got into orange ranching on land the family owned.

Bob served on the Orangethorpe school board in 1949, at a time when the area was experiencing rapid growth and transformation from orange groves to housing subdivisions, and commercial and industrial centers.

Annexation of Orangethorpe

As the cities of Anaheim and Fullerton began to grow and subdivide in the post-World War II years, they each sought to annex Orangethorpe.

“The City of Anaheim learned that Fullerton was subdividing and moving to the west,” Clark remembers. “Anaheim took kind of a spider web strip annexation out through La Plama and expanded it across our ranch and my wife’s folks’ ranch and others.”

The Orangethorpe farmers opposed the annexation, so community leaders organized a sit-down with Anaheim Mayor Charles Pearson and administrator Keith Murdock and Fullerton Mayor Tom Eadington and city engineer Herman Hiltscher.

“We just asked them to come and sit down at the Orangethorpe School House and try to discuss, in a gentlemanly fashion, what was a rational, logical subdivision of the lands, and what each city could do” to serve the landowners with services like water and sewer,” Clark said.

Eventually the cities agreed on a demarcation line that was around what would become the 91 freeway.

According to Galvin, “In 1954, the school district was divided between Fullerton and Anaheim, and the entire Orangethorpe area was eventually divided and annexed to Anaheim, Fullerton, and Buena Park, although a few pockets of unincorporated county territory remained for many years.”

Fullerton vs. Anaheim

Clark remembers that in the early days, Fullerton and Anaheim were very different towns.

“Anaheim…was a swingin’ town. And Fullerton was a very churchy/WCTU [Women’s Christian Temperance Union] town,” Clark said. “On Commonwealth for years, they had several fountains with the little marble plaque dedicated by the WCTU. It said. ‘Drink water’…people would go over to shop in Anaheim…they’d buy their groceries and their can of molasses for the week and then get their can of beer from over at Anaheim because the brewery was there. And sit around and watch each other get haircuts–this was the excitement in those days.”

Post-War Industrial Development

As the tax revenue from the oil fields and orange groves were declining, city leaders approached Bob Clark about attracting industries to Fullerton.

“Anyone with foresight could see that the orange groves were going to give way to housing subdivisions and industry,” Clark said. “Plus the groves were suffering from quick decline. I was the youngest grower, I guess, except for the Eadington family, in the whole valley. There just weren’t any children interested in groves. Well, you couldn’t…make the groves pay.”

Clark became “industrial coordinator” for Fullerton in 1953.

As an orange grower himself, he went to talk to other growers about selling their property for industrial development.

“I could go out there with a country boy approach as an orange grower and talk to them about what do you think about the disposal of your property,” Clark said. “Of course most of them were conscious that the west side was getting subdivisions. And most of the orange growers were getting old, I mean, they’d been in business fifty, sixty years and they were worried about who’s going to take over; our children aren’t interested in raising citrus, the market’s going to pot, our costs are skyrocketing, the tax assessor is making it impossible to raise citrus on these expensive lands. And I would sooth them with the fact that, well, this should be a consolation to you; if the value is growing each year, you’re making more money than you are out of raising crops on the land by just holding your property until you can find a higher and better use for it, and it seems to me that industrial property–industrial land would be the highest and best use in this market since you’re getting $2500 for subdivision land and you can get as much as $4,000 to $4,500 for industrial property to begin with.”

Clark identified the area east of Harbor, between Lemon and Placentia for industrial development.

“Once we put out plants like the National Cash Register and the Moore Business Forms and the first Sylvania plant which were beautiful…plants set back with nice gardens and so on, it was an example that set the pace and people began to go along with the program,” Clark said.

One of the big enticements to industrial businesses was the fact that they had rail access for shipping their product.

He got Kimberly Clark (paper products) and Rheem Manufacturing Company to locate in Fullerton.

He recalled a story about having lunch with Jack Kimberly, and him striking a deal with the railroad in a very Mad Men way: “So Jack Kimbrerly was here and we were having lunch and he said, well, I know that ole buzzard Gurley [from the rairoad company], and I have an idea he’s back at the Athletic Club having a drink about now. And he said, let’s try to get him on the phone and let’s get this thing resolved…and they, of course, it was hi, Jack; hi, Fred, what’s the big hang up…So I got a telegram that stated, you can have anything you want, buster, signed Fred Gurley.”

Other industries he got to locate in Fullerton included: American Meter Company, Arcadia Metal Products, U.S. Motors, and of course, Beckman Instruments.

Fullerton eventually annexed the land that included the Beckman Plant.

“I had to go up on the hills along with Walt Chaffee, the city attorney, and talk to various groups of people–property owners–about the benefits of coming into Fullerton,” Clark remembers.

He remembers getting pushback from the La Habra city attorney Harld McCabe: “Hissing Harold, we called him. Because all McCabe wanted to do, of course, was earn a fee and get some property he had up on Spadra over into La Habra where he could control it–with the La Habra planning commission who were a whole lot more amenable to him…Anyway these things happen: men all have different ideas as to how something develops and mostly…based on whether they make a profit out of it. This is understandable, the name of the game.”

With increased industry in Fullerton, some companies began to work with public schools for vocational training.

“Dr. Beckman donated equipment to local schools for vocational training…to try to make these people of some value when they hit the street after graduation,” Clark recalls. “This was to be permeated down into the shop level where the kids in an auto shop didn’t just come out learning how to bang a few dents out of a fender, but learning how to be a certified welder, or how to operate a punch press…or some of the more technical equipment than they get in the average high school or junior college…it seemed like a great way to employ our youth.”

Although Hughes Aircraft came into Fullerton in 1957, after Bob left Fullerton, he remembers meeting Howard Hughes.

“I met Howard Hughes in the Board of Director’s room quite casually,” Clark said. “He flew in when we were discussing the final phases of the purchase of the land and just ducked his head in the door looking father shoddy in golfer sweater and sloppy pants and just addressed his remarks to Dr. Highland: oh, you’re working on that Fullerton thing, Pat, huh…And Hughes didn’t shake hands: he just nodded the introduction and with a grimace rather than a smile and walked out of the room.”

One other selling point to potential industrialists was the fact that Fullerton had an airport.

“The Hughes people wouldn’t have located here unless they could have had an airport,” Clark said. “They’re very air-minded people and have their own helicopters and…planes…many of the industries used the airport.”

Clark ended his employment with Fullerton in 1956, after three years. He went to work for United California Bank with their industrial business accounts.

St. Jude Hospital

Clark recalls the early establishment and development of St. Jude Hospital in Fullerton.

He remembers that “The [catholic] sisters were pushed around when they first came here…they first had a site out on some property below Chapman’s land on Pioneer and State College. And they were unsuccessful in getting zoning…they were given a slap in the face and turned out.”

“We decided one day that the only way to get a hospital in here is first to use the catholic sisters because they’ve got half a million dollars they could put into it; two, use the industries in north Orange County because they are going to be responsible for the bulk of donations from private sources…the other third was to come from state funds…” Clark remembers.

With all the residential and industrial growth in post war Fullerton, “We had a terrible shortage of hospital beds. What with all the growth going on, it looked like we were really going to be in trouble.”

So Clark and a doctor named Fernandez organized a luncheon at the Greenbriar Inn and invited all the local captains of industry–Arnold Beckman, Hubert Ferry (Union Oil), and representatives of other companies like Sylvania. They donated some funds for the hospital.

“We got the site up by the Fullerton Dam from a private owner, Miles Sharkey, the Sunny Hills Ranch owned that parcel, And he gave it to them at a real nominal fee,” Clark remembers.

Water

When Clark went to work for the city of Fullerton, he was aware of the problem of reduced groundwater.

“It came to us quite closely because we had owned two commercial wells and several domestic wells on our land in the west Anaheim area. And we, of course, could see the water table dropping away from our pumps,” he said. “I was very conscious of it and so was everyone that came in here, like Kimberly Clark and Sylvania…realized that they couldn’t depend entirely on wells, that they would have to have a secondary source of water because the basin was slipping away, and there was no opportunity to replenish it except during wet years when they have excessive runoff up in the mountains.”

In 1954, the Orange County District (OCWD) began importing water from the Metropolitan Water District (largely Colorado River Water) and putting it back into the groundwater basin to replenish it.

Clark was appointed to the Board of Directors of the OCWD in 1967 or 1968.

In 1971, when he was interviewed, he talked about future OCWD projects: a desalination plant (which has never materialized), and a wastewater reclamation plant, which does now exist.

Legacy

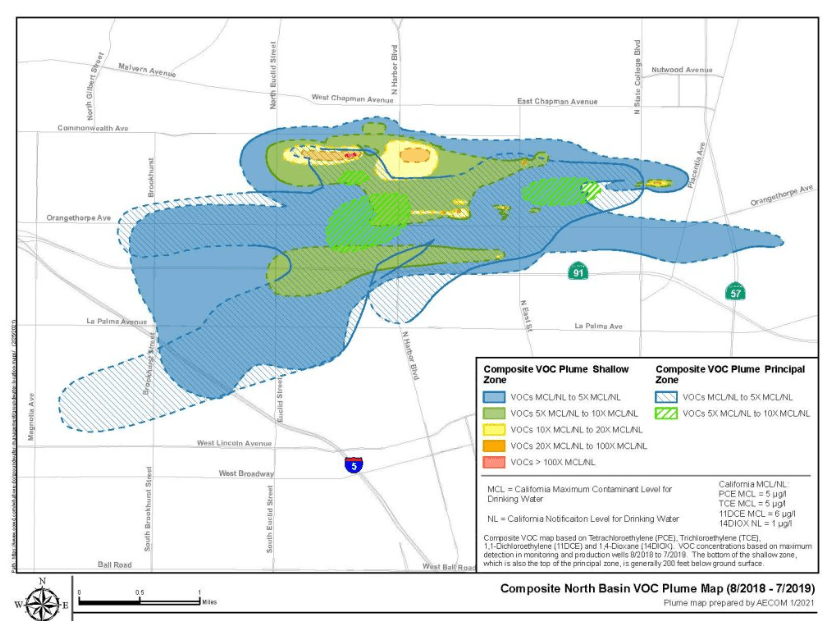

One unfortunate consequence of bringing industry to Fullerton was a legacy of pollution, specifically groundwater contamination. As a direct result of manufacturing in the southern industrial area of Fullerton and north Anaheim, Fullerton now has a Superfund site called the North Basin Contamination, a 5-mile plume of industrial solvents that threaten local groundwater. Here is a map of the plume.

To learn more about the North Basin Contamination site, visit its EPA page HERE.

Leave a comment