The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Raymond Thompson, a former city attorney of Fullerton and a Superior Court Judge, was interviewed twice, in 1968 and 1975, for the CSUF Oral History Program. Here are some things I learned from these interviews.

He was born in Sioux City, Iowa. His family moved to Fullerton in 1911 when he was six years old. His parents were Orvin and Margaret Thompson. He had three sisters: Helen, Janet, and Dorothy.

The population of Fullerton was approximately 1,700 when they first arrived.

His father, who had been a locomotive engineer, decided to get into the automobile business. After taking a course in automobile mechanics at the trade school in Los Angeles, he learned of a garage business that was for sale here in Fullerton that was owned by Lillian Yeager.

“She was the female ‘garagist’ [which was] quite a novelty in those days. She would get under the cars and work and swear, and everything else just like a man, working as a mechanic and carrying on the business,” Thompson recalls. “My father and Mr. Dreyer bought this business which was located at the corner of Spadra and Amerige–the building’s still standing intact. I think there’s a furniture store there now.”

In addition to the garage, the family sold Overland cars, and then Buicks.

According to Thompson, the first automobile in town was owned by William “Billy” Hale, who was a pioneer orange grower and mayor of Fullerton. The car was a 1902 model Saint Louis.

“In those days, we used to have big Fourth of July local events with races of all kinds. Among other things there was an automobile race,” Thompson remembers. “Stock car races started at Commonwealth and Spadra [Harbor], went east to Acacia, north on Acacia to Chapman, back on Chapman to Spadra, and then south on Spadra to the point of beginning.”

In 1912 the first streets were paved in Fullerton–Spadra from Chapman to Santa Fe and then a block east of each of the intervening streets, Commonwealth, Wilshire, Amerige, and Santa Fe.

His father’s garage “was like an old-fashioned country store. You could get anything and everything that related to the automobile. It took the place of the service station. They came there to fill their gas tanks, get oil, and have their cars greased. We had a shop with two or three mechanics that did complete overhauls, repairs of all kinds, washed cars, rented cars with or without a driver, retread and vulcanize tires, the whole bit. It was a fairly big enterprise actually, and very versatile.”

Thompson remembers the old Atherton ostrich farm.

“That was quite an institution here in Fullerton,” he said. “The Athertons who were sort of characters had this ostrich farm. They raised them for feathers.”

A few years after arriving in town, his parents bought a lot on what was then North Spadra, on the corner of Spadra and Brookdale. The lot cost $450 and the house, to build, was $2,500. At first there were all walnut groves in back of the house, then Brookdale was built through the grove and frame homes were built. The family lived there for many years before selling the house in the 1950s.

In those early days, the town was able to build good schools, in part, because of the revenue from local oil production and citrus groves.

“So much of the economy was dependent on the orange industry,” he said. “Not only the growers, but the merchants, the people with the garages, the bankers, and everyone else were all largely dependent on citrus.”

He remembers how, in those days, “we could always look out and see the mountains…The word smog was not in the vocabulary at that time.”

He remembers the old Stern and Goodman general store, which became the Stein and Strauss store. This was one of the first buildings in Fullerton, at the corner of Spadra (Harbor) and Commonwealth.

“They had groceries, dry goods, farm implements and they dealt in hay and grain…You could get anything from a needle to a threshing machine,” he said. “The farmers…would come all the way from as far as Puente, north, and as far as El Toro, south. Some of them would come just once a year with their big wagon and their team…Stern and Goodman carried these farmers until the next crop came, maybe for a year. If there would be a crop failure, maybe they would have to carry them another year. It was a real big operation, and quite picturesque.”

The owners of the store were two Jewish men who had come from Germany, They had a branch store in Olinda, and another in Yorba Linda.

By loaning products to farmers, Jacob Stern eventually acquired a lot of land, should the farmers default.

“[Stern Realty] had land all over Southern California,” he said.

He remembers the Benchley family, who “were very colorful people, rather sophisticated for a little town like Fullerton. The old gentleman, maybe in his early seventies, always dressed just as sportily as any young man in town, in fact, more so. He’d buy his clothes in expensive stores in Los Angeles or San Francisco, and he smoked cigarettes. Oh, gosh, in those days that really raised eyebrows! They mingled with the high society in Los Angeles…But he was a good citizen and contributed a great deal to the upbuilding of the community.”

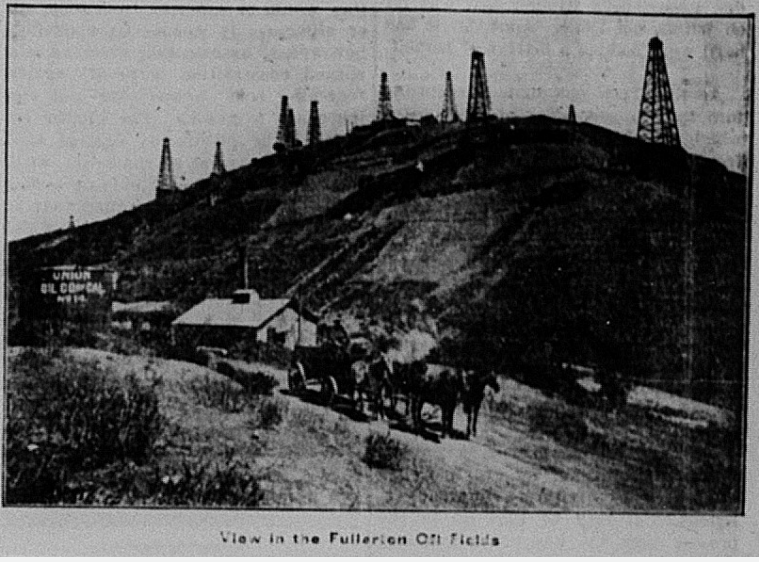

He remembers the oil fields north of town–the company town of Olinda, and how oil magnate Edward Doheney first struck oil there.

“There were many wells being drilled and many men coming to work in the oil fields. The oil companies put up barracks and boardinghouses, so there was a bunch of rough, single guys, oil drillers, what they called roughnecks. It was something like an old-fashioned mining community with a pretty rough and ready, reckless bunch of men like you would expect in any sort of a situation where there were mostly a bunch of vigorous young men…and then later on, the oil companies built lots of homes for their workers and lots of families lived all through the hills around Olinda and then over between Olinda and Brea. Brea was a similar community.

There was lots of oil, and many people worked in the oil fields, drillers, pumpers, and so forth. I remember Olinda was kind of a boomtown. Lots of single men were working there, and it was a pretty dangerous occupation before they had taken so many safety measures in industry. I remember quite a few times seeing the cars serving as ambulances roaring through town with their horns going, bringing some injured worker to the hospital. Then it had a little bit of the aspect of a wide open mining town, but workers would mainly go to Anaheim.

Anaheim was a “wet” town, where you could buy liquor, and Fullerton was a “dry” town, “so on Saturday night Anaheim would be the place to go.”

As for leisure activities, he remembers that “nice people didn’t go to the pool hall. That was more for the “roughs” and the guys that came in off the farms on Saturday night and that sort of thing.”

He remembers there were dances: We’d go down to Balboa, to the old Pavilion for dances, and…the picture shows and confectionary shops. We’d go in and get a big ice-cream soda or an ice-cream sundae.

He remembers taking his shotgun and trudging over the hills to the Bastanchury Ranch to hunt rabbits.

Thompson attended the original red brick Fullerton Grammar School (on Wilshire and Pomona, which no longer exists).

He graduated from Fullerton Union High School in 1922. The current high school was actually the third school high school location. The first was at Wilshire and Lawrence (now a Fullerton College parking lot), the second was where Amerige Park is now located. This one burned down, and then in 1911, the high school moved to the present location on Chapman.

His recollections of principal Louis E. Plummer were that he was “something of a disciplinarian so that he was a bit austere. He was respected, but there wasn’t quite the affectionate feeling that a warmer person would have inspired.”

His first year in high school, during World War I, they had military training.

“I remember we drilled, marched, had our uniforms, and our wooden rifles,” Thomson said.

During World War I, he remembers “the boys going away, but even then it was kind of a big adventure. I remember seeing them in uniforms, down at the depot taking the train. Lots of young men I knew, like Fred Strauss and Raymond Smith, Mickey Ford, and the Sherwood boys, Raymond Starbuck, just lots of them, and Dr. William Wickett, Sr.”

Football was an important school activity, “especially to beat Santa Ana.”

During Prohibition, he remembers that bootleggers used to smuggle liquor along the Orange County coast.

“Lots of it got in, and I remember that some of the old-time sheriffs, reputedly, were tolerant of the bootleggers and the smugglers, even cooperated to a certain extent or looked the other way. Liquor was available in Orange County. There were stills out in the hills and mountains. The Basque people traditionally have their wine and their brandy, and they never recognized prohibition. They still grew their grapes and made their wine and their brandy,” he recalls.

Thompson has distinct memories of the Ku Klux Klan in Fullerton in the 1920s: “There were a lot of good people who had been longtime friends, Catholics and Protestants, and a lot of prejudice and feeling was triggered. There was a Ku-Klux Klan organization. Of course, the Catholics and Jews were very bitter toward the Klansmen…the communities, Fullerton and Anaheim got pretty well lined up. The Masonic Protestant Ku-Klux Klan was the real far-out fringe of those groups, as against the Catholics and the Jews on the other side. I remember the bitterness and it entered into the municipal elections. It was pretty bitter.”

He remembers that W. J. Carmichael had a cross burned on his lawn although Carmichael was not Jewish and was not Catholic.

Dan O’Hanlon, an Irish catholic who was opposed to the Klan, also had a cross burned on his lawn.

Thompson remembers that the issue of Prohibition was a big one for the Klan.

“The Klan favored Prohibition, so maybe that was partly in the background,” he said. “It kind of dissipated over the years. The people settled down and forgot about it. The old friendships were renewed and I don’t think people pay much attention to it anymore.”

He remembers the Bastanchury family, who were Basque sheepherders who had about 6,000 acres. The family got involved in oil and oranges.

“They started the largest orange grove in the world,” he remembers. “They had 3,000 acres, planted in oranges, up where the Sunny Hills area is now. They were very picturesque people. They were gay, they had their big fiestas and their barbecues, lots of fun and rather easy going, improvident sometimes, and they went under about 1929. Unfortunately, the Bastanchury boys all died poor.”

Unfortunately, the Bastanchurys got screwed over oil.

“[The] Murphy [oil company] leased the property for oil, then drilled a well and found oil, but came back and told the Bastanchurys–the old man was perhaps illiterate, at least had very little education–that there was no oil, plugged up the well, then later came back and said that there were some clay deposits that he [Murphy] was interested in. He bought this 3,000 acres for about $60 an acre. Then ten or twelve years later, after the younger generation, the sons, had been to college and realized how the family had perhaps been defrauded, filed a suit for $72 million. Because of the time element and the problem of waiting so long, they settled it for $1.2 million.”

With the money from this settlement, the Bastanchury sons planted orange groves. Unfortunately, they overextended “and then came 1929 and the Depression.”

After high school, Thompson spent one year at Fullerton Junior College, then went to USC, where he got his law degree. After graduating from USC in 1927, he practiced law in Fullerton. For a time he had a law practice with Mr. Albert Launer.

Thompson remembers the Great Depression.

“Money was scarce and farmers and orange growers couldn’t pay their mortgages. There were foreclosures and after a while moratoriums came along that gave them some relief,” he said. “I remember the banks were closed for awhile. You couldn’t write a check against your account. There was hardly any money.”

He remembers the 1933 Long Beach earthquake.

“I recall people coming into the area from Long Beach driving through Fullerton, driving up on the hills and spending the night in their cars. Many of the people here stayed out all night in their cars and in their yards,” he remembers. “It really shook and you could see the earth wave and the orange trees shake back and forth, like the waves of the ocean. We had a lot of damage in our Fullerton schools.”

He served as city attorney for five years from 1937 until he was appointed by Governor Warren in 1944 to the Superior Court.

Reflecting on the growth of Fullerton, Thompson said, “Our beautiful community is a thing of the past. It is now subdivisions, factories, smog, freeways, and congestion. Of course, what it would have been otherwise is another question. If we had not progressed and had severe economic problems, we might be more unhappy than we are now. A lot of people made a lot of money. The orange growers who sold out, sold at high prices and the ones that invested wisely and saved some of it are in pretty good shape.”

Leave a comment