The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Jennie Reyes and her husband John owned a Mexican restaurant called La Perla on Truslow Avenue in Fullerton (in what she called the barrio) for nearly thirty years, from the 1940s to the 1970s. Reyes was interviewed in 1975 for the CSUF Oral History Program. Below is what I learned from reading the interview, which chronicles a time when Mexican immigrants in Fullerton were mostly segregated south of the tracks and many lived in citrus work camps. Though she experienced hardship in her life, Reyes’ story is an inspiring one. La Perla was an important community hub that was unfortunately demolished to make way for an underpass on Lemon St. in 1975.

Early Life

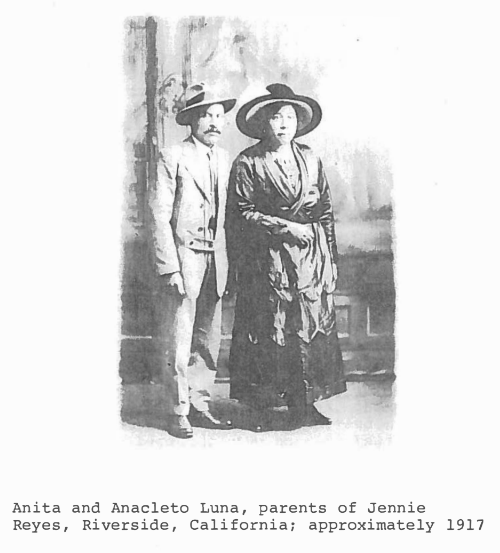

Her parents immigrated from Mexico from the state of Guanajuato and settled in the Casa Blanca barrio in Riverside around 1917. Her parents had nine children, all born in Riverside, but only three lived long enough to be married. The rest of them died when they were small.

“In those days there were so many diseases: whooping cough, measles and all that sort of thing…We struggled and we worked,” Reyes said. “We were very poor.”

Jennie started working in a packinghouse at age thirteen.

“In those days, they weren’t so very strict about sending their children to school, especially with the Mexican people. Let’s face it, it was in Casa Blanca…I don’t think they cared whether we went to school or not.”

“In those days it was very hard for us to get anything done and to be accepted in any kind of work [other than agriculture],” Reyes said. “Let’s face it, there in Casa Blanca there were nothing but Mexican, Japanese and a few Italian people at that time.”

Reyes recalls experiencing segregation and prejudice in Riverside.

“If you would go to the show–they had one theater in Riverside–there was a place for you [Mexicans]. You couldn’t sit where everybody else did, where all the Anglos would go. We had a section where we had to sit if we wanted to go to the show,” Reyes said. “As far as jobs, there were no jobs for the Mexican people, not even as a clerk in the store, not even that. All we would do is work in packinghouses, pick tomatoes in the fields, pick walnuts, pick prunes, pick cucumbers, strawberries and blackberries.”

“Because we knew that we were not wanted in other jobs so we just segregated ourselves to what we could do, where they could accept us,” Reyes said.

Her father got a job as contractor, bringing Mexican workers from Casa Blanca to El Monte to pick walnuts. Eventually the family bought a lot in El Monte, where her father built a home.

“We used to have the relatives come and stay with us and they would put their tents up in the backyard. From there we could go to work,” Reyes said.

Reyes’ family then moved back to Riverside, purchasing a house in Casa Blanca. The family would travel north to the town of Hillsborough to pick prunes when they were in season.

“The first year we worked for them they let us camp in a big barn. It was so big you could put five little tents inside. Those were our living quarters during the prune picking,” Reyes said. “After they got to know us better, they let us into their home and we used their washing machine, which we never used at home because we didn’t own one.”

When she was 13, her parents separated “and things were a little harder.”

“I had two brothers…I was the mother of them,” Reyes said. “I stayed with my father and my ‘children.’ I called them my children because they were my two brothers and I took care of them until they got married.”

Life in Fullerton/La Perla

When she lived in Riverside, Reyes used to come to work during the orange season in Placentia and Fullerton in packinghouses. Her future husband John used to make boxes in the packinghouse right next to hers.

“That’s where I met him, there in the packinghouse,” Reyes said.

John and Jennie were married in Riverside in the early 1940s.

A friend of John’s was in the business of delivering merchandise to different restaurants and he heard about a restaurant that was for sale in Fullerton’s barrio on Truslow, so the newly-married couple bought it. They moved in the little room in the back of the restaurant.

“The people we bought the restaurant from…cheated us,” Reyes said. “They asked a high price for it and they were supposed to leave a lot of things there which they didn’t.”

Despite this, the couple worked hard to build a successful Mexican restaurant.

“The menus and all the food that I prepared there, I just tried to prepare everything like I would at home, and some of the recipes from my mother that she had taught me to cook,” Reyes said.

Her husband also continued to work making boxes for a packinghouse in Placentia and then after that he went to work for the Mississippi Glass Company.

She remembers when Saint Mary’s church burned down: “It was a shock because we went to mass and here was the church burned down. Then we used to go to mass there at the Boy’s Club.”

Reyes remembers serving a large clientele of Mexican farm workers, and she would help them send money and letters back to their families in Mexico.

“Every Monday I used to spend about four hours at the bank to make all those money orders and to get the money orders ready to send, and to register their letters and all that,” she said.

She would also help translate for Mexican workers.

“They couldn’t speak English. They didn’t know where to go to, who to go to, who was going to take advantage of them, who was going to be honest to them,” she said. “If I would go to town shopping and I’d see somebody there, and some of them didn’t know English they’d say, ‘Could you interpret for me?’ I’d say, Sure. I was always glad to do it for them.”

There were at this time Mexican work camps in Fullerton.

“The Eadington Company had a small camp there across the street from where we had our restaurant in which they accommodated their sixty workers. In fact we had them as boarders in our restaurant for one year,” she remembers. “I had to get up at two and three o’clock in the morning and make three hundred sixty flour tortillas to fix their lunches and than at six o’clock we would give them breakfast and they would leave for work and take their lunches and then they would come home in the evening at five o’clock or five-thirty to have their dinner and they would leave.”

Her children all graduated from high school.

Eventually the family moved into a house at 315 South Lemon, near their restaurant.

The restaurant became a popular gathering place, not just for Mexican workers, but for all kinds of people in town.

“We had a wonderful clientele. Doctors, people from offices would go there; nurses from Saint Jude’s; people from the Motor Vehicle Department. They used to come every Friday from Autonetics,” said said. “It was like a family thing.”

“Even though it was a barrio, I was happy there. We were happy,” Reyes said.

The Death of John

Eventually her husband John got sick with Osler-Weber-Rendu’s disease, a rare blood disease that prevented him from working and required that he get regular blood transfusions and sometimes spend weeks at the hospital.

The family struggled to pay for John’s care on their income from the restaurant. During those difficult thirteen years, the community helped out a lot, such as the Sisters of St. Joseph of Orange who provided service and medication for Mr. Reyes at nearby St. Jude Hospital and never sent a bill.

A 1970 article in the catholic publication The Tidings told the Reyes’ story shortly before Johnny died.

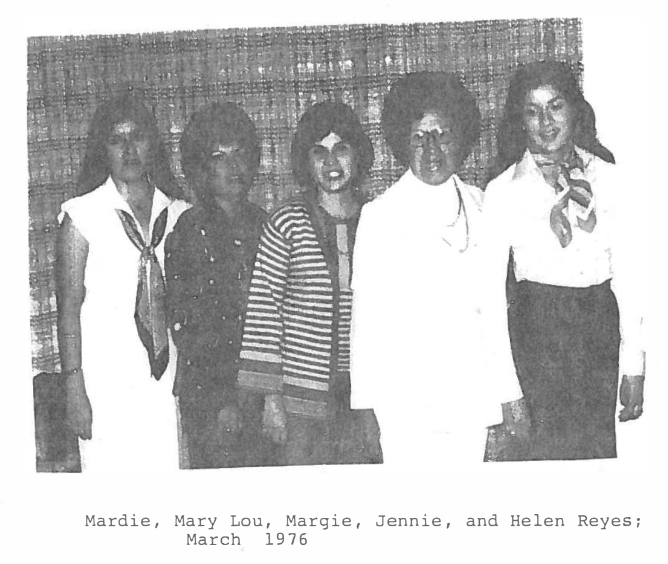

“This is a Mexican love story. It takes place here at La Perla, a little restaurant in this town’s old barrio. It ls the story of John Reyes – a man kept alive for 11 years by much love and two pints of blood each week,” the article stated. “La Perla, at Truslow and Lemon Sts., is next door to the Reyes’ old frame house. It is where Jenny has worked 12 hours a day – for years, to support John and their four daughters, Mary, Margaret, Martha and Helen.”

John passed away on August 15, 1970.

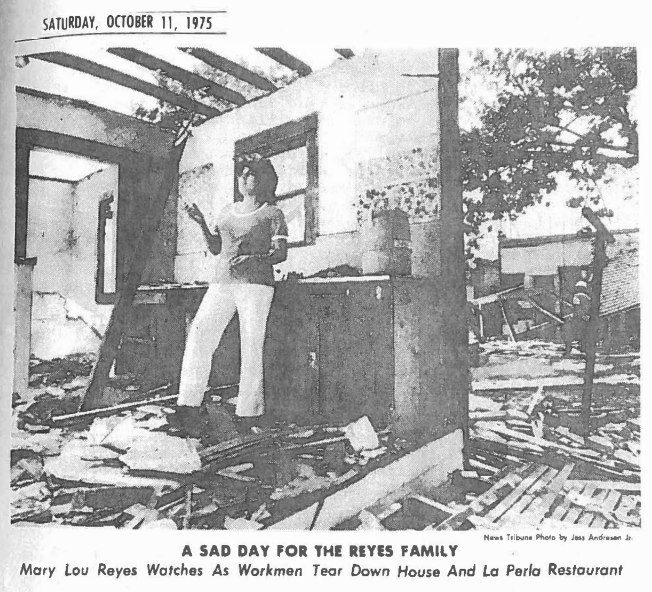

The Restaurant and Family Home are Demolished to Make Way for an Underpass

A 1975 Fullerton News Tribune article entitled “Progress Uproots a Family” stated that the city of Fullerton used eminent domain to condemn the site of La Perla and the Reyes house, along with other neighbors “to make way for an underpass on Lemon Street at the railroad tracks.”

“I just can’t go see my house being torn down,” said Mardie De La Torre, one of Reyes’ four daughters. “That house and the restaurant represent the blood, sweat and tears of my entire family…’People don’t realize what it is like being forced to leave the home where you have lived all your life,” she said.

Reyes remembers, “It hurt us so much when we were moved out of there…because of the underpass. Don’t get me wrong. I don’t want to be selfish; I believe in the betterment of the town and everything…but I don’t believe it was a fair price.”

Other small businesses that catered to the barrio residents, such as Negrete Market, were also torn down.

“What I think makes it so bad is that some of the people from that area are very poor. Some of them have a car, you know, but some of them don’t and it makes it hard for them to go to the shopping centers,” Reyes said. “It’s going to help the traffic but how is it going to help all those people in that area?”

City Attorney Kerry Fox defended the city’s position. “We follow the law, we don’t set the law,” he said. “Whether the laws are fair – that’s not my business.”

“They think about the betterment of the city, of the town, [but] they don’t stop to think of the sacrifice some people will have to go through,” Reyes said. “The barrio, especially there where the Mexican people live, all the other people who were there moved out to better homes and left all the poor people there with no help.”

With the destruction of their home and business, the Reyes family relocated to Placentia, which is where Jennie was living when she gave the interview in 1975.

Leave a comment