The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

“This is an era of town building in Southern California, and it is proper that it should be so, for the people are coming to us from the East and from the North and from beyond the sea, and from this great multitude whose faces are turned with longing eyes toward this summer land and who will want homes among us, we must provide places.”

–Pasadena Daily Union, 1887

The City of Fullerton was founded in the year 1887. This was a crucial year in the history of Southern California, as it was the peak of a massive land and population boom.

In the span of just two years (1887 to 1889), over sixty new towns were established in Southern California and an estimated 2,000,000 new people arrived in the region. It is estimated that the value of real estate transactions for the year 1887 alone was over $200,000,000.

I recently finished reading Dr. Glenn Dumke’s book The Boom of the Eighties in Southern California which deals with this time period. In the interest of understanding the wider context of what occurred locally, I present here a summary of what I learned from this book as well as a chapter from Carey McWilliams’ book Southern California: an Island on the Land entitled “Years of the Boom.”

According to Dumke, there were at least three main causes of the boom–agricultural expansion, a rate war between rail companies, and extensive advertising and publicity by those seeking to profit from the boom. I’ll address each of these separately before going into how the boom affected different areas of Southern California, including Fullerton.

The 1880s were, of course, not the first population boom in California. There was the Gold Rush of 1849, followed by a series of lesser booms, as the formerly Mexican province transitioned into an American state, and the large ranchos began to be subdivided into smaller farms.

“Agricultural development brought prosperity, prosperity brought fame, and fame attracted new settlers,” Dumke writes. “Of all the causes of the boom, agricultural expansion was the most substantial and constituted a foundation solid enough to withstand the blow of the collapse.”

The Railroad Rate War of 1886

A more immediate cause of the boom was a rate war between the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe railroads, which took place in 1886.

“The reduction of fares to unheard-of levels stimulated the migration of hordes of people who would otherwise have confined their interest in California to reading about it,” Dumke writes.

In the mid-1880s, the Southern Pacific (SP) railroad was an extremely powerful economic and political force in California. The owners of the SP were known as the “Big Four” or “The Associates”: Leland Stanford, Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins Jr., and Charles Crocker. These guys were good at heading off competition for the lucrative freight and passenger rail services to, from, and within California.

However, in 1885, the competing Santa Fe Railroad completed a route to Los Angeles, bought up some local rail lines, and aimed to take the Southern Pacific head on.

“The completion of the Santa Fe line in 1886 was the spark that ignited the real estate explosion of the ‘eighties,” McWilliams writes. “Previously the passenger rate from Missouri Valley points to Southern California had been approximately $125. But the rate promptly dropped to $100, when the Santa Fe entered California, and continued to fall as each line undercut the other. On March 6, 1887, the Southern Pacific met the Santa Fe rate of $12. In a matter of hours, the rate dropped to $8, then to $6, then to $4. By noon on March 6, the Santa Fe was advertising a rate of $1 per passenger.”

“The result of this war,” wrote a local historian, “was to precipitate such a flow of migration, such an avalanche rushing madly to Southern California as I believe has no parallel.”

According to Dumke, “The Southern Pacific’s arrival increased Los Angeles’ population one hundred percent, and the ensuing arrival of the Santa Fe increased it 500 percent.”

Advertising Southern California

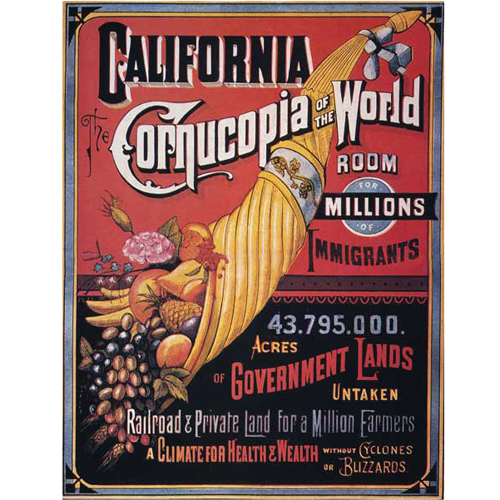

Another basic cause of the boom was the extensive advertising and publicity campaign which carried information about southern California to all parts of the world.

This advertising took many forms ranging from railroad propaganda to newspaper stories and ads to letters from residents writing to their friends and families extolling the Golden State.

“Much of the publicity was financed by railroads, primarily the Southern Pacific, for two main purposes: to sell their own [government] granted land, and to induce a large population, whose future business and travel would be profitable, to settle along their lines,” Dumke writes.

The railroads would employ agents and writers “expounding the glories of the West.”

Some of these writers and their works include Jerome Madden (author of California: It’s Attractions for the Invalid, Tourist, Capitalist, and Homeseeker), and Charles Nordhoff whose California for Health, Pleasure, and Residence, was given “more credit for sending people to California than anything else ever written about the section.”

In addition to the railroad companies, local chambers of commerce, boards of trade, and realty syndicates helped promote the land boom.

“These four types of publicity–descriptive accounts, railroad propaganda, newspaper and local agency material, and, finally, the work of enthusiastic residents–combined to make Southern California perhaps the best-advertised portion of the country during the third quarter of the 19th century,” Dumke writes.

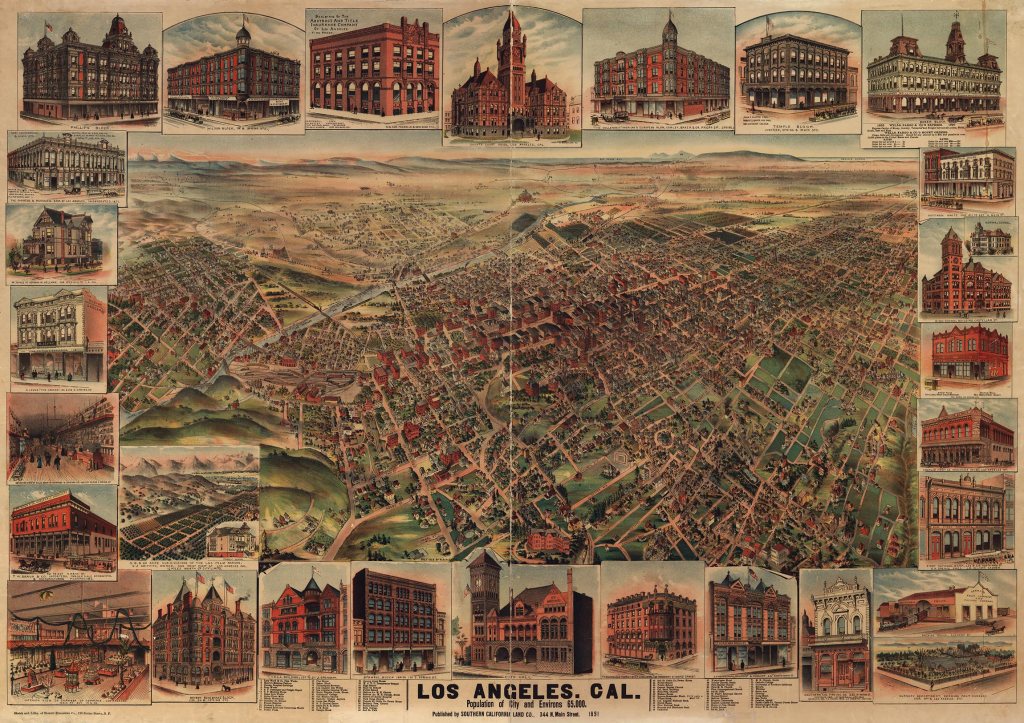

The Boom in Los Angeles

While the boom of the 1880s spread throughout Southern California, its epicenter was Los Angeles.

According to McWilliams, at the peak of the boom, “More than two thousand real estate agents paced the streets of Los Angeles, seizing lapels and filling the balmy air with windy verbiage. Business blocks sprang up like toadstools, and residences sprawled far beyond earlier city limits. Railroads, formerly sluggish, suddenly traced for themselves with lizard-like speed a complex network of trackage.”

Some of the land promotion took on a carnivalesque aspect.

“Men stood excitedly in line for days at a time in order to get first choice of lots in a new subdivision. Flag-draped trains hauled flatcars jammed with enthusiastic prospects to undeveloped tracts far from centers of settlement. Exuberant auction sales, accompanied by brass bands and free lunches, helped sell $100,000,000 of Southern California real estate during the boom’s peak year,” McWilliams writes. “Unscrupulous promoters with empty pockets and frayed trousers bought on margin and found themselves quickly rolling in wealth, while old landowners who scoffed at the excitement were eventually sucked into the maelstrom and reduced to poverty. Empty fields and riverbeds and tracts of worthless desert land were platted solemnly into twenty-five foot lots–and sold.”

Dumke writes, “The year 1887 was the kaleidoscopic peak or boom excitement for all of southern California. When 1886 saw an influx of thousands of tourists and immigrants…the spring of the next year brought with it…the arrival of tens of thousands, who crowded the trains overflowing and loudly demanded a place to stay and spend their money. The population of Los Angeles was estimated to have increased from 11,000 to 80,000 during the boom years, and most of the increment undoubtedly came in 1887. Inhibitions and conservatism vanished. The gold was there for the taking, and aggressive noisiness carried the day.”

Some Los Angeles county towns that were created during the boom include Hollywood, Inglewood, Santa Monica, San Pedro, Catalina Island/Avalon, Alhambra, Pasadena, Glendale, Burbank, San Fernando, Pomona, and more.

The Boom in Orange County

“Perhaps the greatest effect the boom had on the Santa Ana Valley was to inspire the formation of a new county–the present Orange County,” Dumke writes.

Orange County, which would break away from Los Angeles County in 1889, saw much subdivision and town-founding during the boom.

“The largest community [in Orange County] laid out during boom years–was Fullerton,” Dumke writes. “This prosperous city was platted by the Pacific Land and Improvement Company in 1887. The heads of the organization were the Amerige brothers, Edward and George, who sold out a grain business in Boston to establish a town on 430 acres of land north of Santa Ana…While the Santa Fe greatly encouraged the Amerige project, the town was never able to take full advantage of the railway’s arrival, for the first train did not come until the fall of 1888, when the flurry was in its decline. Under the circumstances, the community experienced a rather slow growth and has seen most of its expansion in more recent years, thanks largely to near-by oil fields and Valencia oranges groves.”

The End of the Boom

“Despite hopeful prognostications and repeated assurances by both buyers and sellers that the boom had come to stay, the spring of 1888 witnessed a rapid decline in land values and in buying enthusiasm,” Dumke writes.

“It should be noted, however, that while the boom had collapsed, it had left a substantial deposit of wealth and population,” McWilliams writes.

Los Angeles increased in population from 6,000 in 1870 to 50,000 by 1890.

This increase in population and growth of new towns led to more churches, theaters, meeting halls, newspapers, schools, railroads, and more.

Ghost Towns

Of course, not all towns laid out during the boom survived.

“Of more than one hundred towns platted from 1884 to 1888 in Los Angeles County, sixty two no longer exist except as stunted country corners,” Dumke wrote in 1944. Of course, subsequent development and later booms would see more of the land developed and more towns formed.

Here are some of the Southern California boom towns that failed: La Bollona, Rosecrans, Waterloo, Ramona, Chicago Park, Gladstone, Rockdale, Ivanhoe, Dundee, Maynard, Lordsburg, Piedmont, St. James, Carlton, Richfield, and Fairview.

Impacts of the Boom

“The boom brought people to California in ever increasing numbers, and they themselves were the foundation for a greater economic structure. It enlarged transportation facilities and municipal development, settled hitherto barren areas, completed the breakup of the ranchos, and was largely responsible for southern California’s modern publicity-consciousness,” Dumke writes.

The increase in population and expansion of farms as a result of the boom led to many improvements in irrigation and access to water.

“Twelve irrigation companies were organized during the boom years 1886-88, and the remainder were started largely by the stimulus given their respective areas through boom settlement,” Dumke writes.

The boom was also an impetus for education.

“Out of the boom came a number of educational institutions, well in advance of the actual settlement of the region, such as the University of Southern California, the Chaffee College of Agriculture at Ontario, Occidental College in Los Angeles, the state Normal School (now UCLA), St. Vincent’s College (now Loyola University), Whittier College, La Verne College, and Redlands University,” Mc Williams writes.

Here are some other Southern California cities that owe their beginnings to the boom: San Dimas, Ontario, Upland, Claremont, Chino, Rialto, Fontana, Redlands, Hemet, Oceanside, Encinitas, La Jolla, and Escondito.

Leave a comment