The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Earlier this week, I posted a report on a chapter entitled “The Indian in the Closet” from Carey McWilliams excellent 1946 history Southern California: an Island on the Land. This chapter seeks to destroy the popular myth that the indigenous peoples of Southern California were treated kindly in the Missions of the 1700s and 1800s. Instead, the picture that emerges from the historical record is one of mistreatment and alarming population collapse among the native people.

So how is it that, for decades, elementary school children and visitors to the Missions were told this “happy mission” story, which is so at odds with the unpleasant truth?

In another chapter entitled “The Growth of a Legend,” McWilliams charts the origin of the “happy mission” myth.

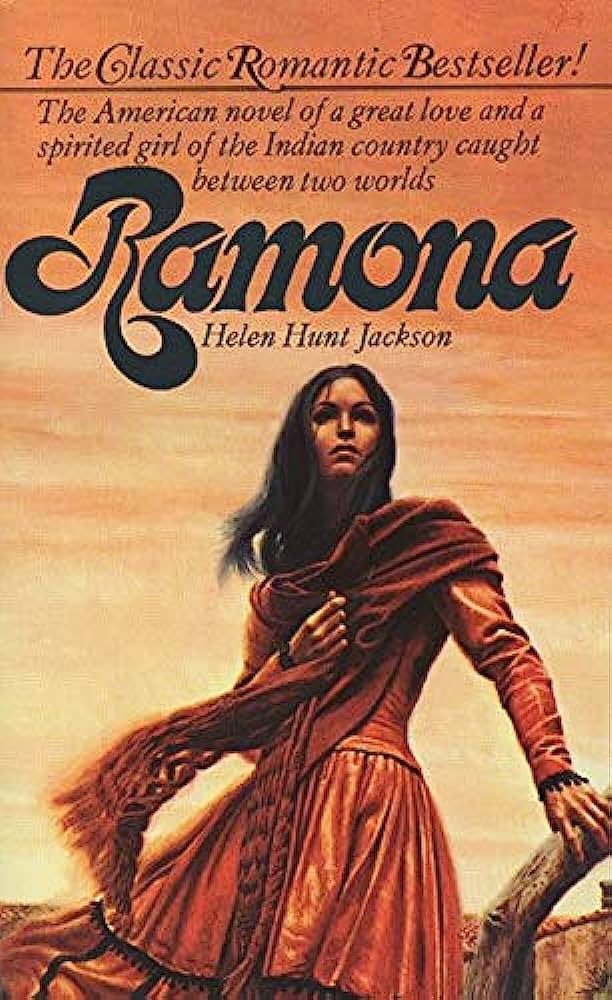

McWilliams pinpoints the origin to one woman, a New England romance writer named Helen Hunt Jackson, whose 1884 novel Ramona became a national sensation and prompted an American fascination with the Missions and California’s Spanish past.

Jackson was born in 1830 in Amherst, Massachusetts. According to McWilliams, she “became a successful writer of trite romances and sentimental poems unlike those written by her friend and neighbor, Emily Dickinson.”

At a Boston tea party, Jackson first became interested in native Americans, particularly their mistreatment. She published a book entitled A Century of Dishonor in 1880, which, as the title suggests, sought to highlight the mistreatment of native Americans.

Jackson then visited Southern California, where she became fascinated by the Missions.

However, according to McWilliams, “Her knowledge of California and of the Mission Indians was essentially that of the tourist and casual visitor. Although she did prepare a valuable report on the Mission Indians based on a field trip that she made with Abbot Kinney of Los Angeles, most of her material about Indians was second-hand and consisted, for the greater part, of odds and ends of gossip, folk tales, and Mission-inspired allegories of one kind or another.”

It was these visits to Southern California that inspired Jackson to write Ramona, “the first novel written about the region, which became, after its publication in 1884, one of the most widely read American novels of the time. It was this novel which firmly established the Mission legend in Southern California.”

While the book was well-intentioned–seeking to generate sympathy for the plight of the native people of California, its romantic evocation of the Spanish past (particular the Franciscan padres, and the Spanish dons) instead served as a driver of tourism and real estate in the region, rather than a genuine engagement with the real history or present circumstances of Southern California native people.

“The book was perfectly timed…to coincide with the great invasion of homeseekers and tourists to the region,” McWilliams writes. “Beginning about 1887, a Ramona production, of fantastic proportions, began to be organized in the region.”

In the late 1880s, there was a huge real estate boom in Southern California, for which the Ramona myth and all it evoked served as a big draw.

Allow me a lengthy quote from McWilliams”

“Picture postcards, by the tens of thousands, were published showing ‘the school attended by Ramona,’ ‘the original of Ramona,’ ‘the place where Ramona was married,’ and various shots of the ‘Ramona country.’…it was not long before the scenic postcards depicting the Ramona Country had come to embrace all of Southern California. In the ‘eighties, the Southern Pacific tourist and excursion trains regularly stopped at Camulos, so that the wide-eyed Bostonians, guidebooks in hand, might detrain, visit the rancho, and bounce up and down on ‘the bed in which Ramona slept.’ Thousands of Ramona baskets, plaques, pincushions, pillows, and souvenirs of all sorts were sold in every curio shop in Los Angeles. Few tourists left the region without having purchased a little replica of the ‘bells that rang when Ramona was married.’…A bibliography of the newspaper stories, magazine articles, and pamphlets written about some aspect of the Ramona legend would fill a volume. Four husky volumes of Ramonana appeared in Southern California: The Real Ramona (1900), by D.A. Hufford; Through Ramona’s Country (1908), the official, classic document, by George Wharton James; Ramona’s Homeland (1914), by Margaret V. Allen; and The True Story of Ramona (1914), by C.C. Davis and W.A. Anderson.

Due to its immense popularity, Ramona was also adapted into a highly successful play, at least three motion pictures, and numerous annual pageants, especially the one in Hemet, which is still performed to this day.

As part of this renewed interest, writer Charles Fletcher Lummis formed an Association for the Preservation of the Missions (which later became the Landmarks Club).

Beginning in 1902, Frank Miller began to build the enormous Mission Inn in Riverside, which prompted a revival of Mission architecture. It was at the Mission Inn that writer John Steven McGroarty wrote his famous Mission Play, which premiered at San Gabriel in 1912 and was seen by millions over the years.

This romanticized depiction of the past created a kind of dual identity for the native people of Southern California–the noble Indian of the novel, plays, films, and pageants vs. the actual, flesh and blood Native Americans who were still present in the region.

“The region accepted the charming Ramona, as a folk-figure, but completely rejected the Indians still living in the area,” McWilliams writes. “A government report of 1920 indicated that 90% of the residents of the sections in which Indians still live in Southern California were wholly ignorant about their Indian neighbors and that deep local prejudice against them still prevailed.”

Leave a comment