The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

As part of my research into the history of Fullerton, I occasionally read books about broader California history, to give appropriate context for what occurred locally. I’m currently reading Carey McWilliams’ excellent 1946 book Southern California: an Island on the Land. McWilliams writes the kind of history that resonates with me, with a particular interest in questioning popular myths, and exposing unpleasant but vital aspects of history. I have previously published a book report on McWilliams’ devastating book Factories in the Field: the History of Migratory Farm Labor in California which sought to expose the oppressive and often racist history of how California’s field workers have been treated.

In Southern California: an Island on the Land, McWilliams includes a chapter entitled “The Indian in the Closet” which seeks to destroy popular myths and expose the unpleasant truth of how southern California’s indigenous people fared under Spanish, Mexican, and American rule. Granted, the book was published in 1946, and much additional scholarship has been done since then, but his chapter is nonetheless filled with excellent (and often disturbing) historical facts. Therefore, I have decided to write a mini-report on this chapter, which quotes liberally from McWilliams.

The Myth of the “Happy Missions”

How did it come to pass that, for decades, elementary school children and visitors to the 21 California Missions were told a story of a pleasant and benevolent relationship between the native Californians and the Franciscan padres like Father Junipero Serra?

McWilliams actually includes a separate chapter entitled “The Growth of a Legend” which tells the tale of how, in the late 19th and early 20th century, a Mission myth was created and perpetuated by American writers like Helen Hunt Jackson, John Steven McGroarty, George Wharton James, and Charles Flecther Lummis.

“With a boldness more comic than brazen, the synthetic past has been kept alive by innumerable pageants, fiestas, and outdoor enactments of one kind or another, by the restoration of the Missions; and by the establishment of such curious spectacles as Olvera Street in the Old Plaza section of Los Angeles,” McWilliams writes.

I plan to write more on this, but suffice it to say that this happy story was a myth created not by Indians or Spaniards, but by Americans as “part of a grandiose real-estate ballyhoo” and as a way for Americans living in a place that had undergone rapid social transformation to create a comforting past.

“Before explaining how this legend came into existence it might be well to take a look at the facts,” McWilliams writes.

The Indigenous Peoples of Southern California

Many of the cities of Southern California are actually built upon native village sites.

“The reason is a simple one,” McWilliams writes, “the Indians chose the most favored spot with a sure knowledge born of long experience in the region. He sought fresh water, a scarce commodity in early days; a smooth shoreline; and abundant vegetation. The Indian village of Yang-na became Los Angeles; Sibag-na is now San Gabriel; while Santa Ana is located on the site of the Indian village of Hutucg-na.

Prior to Spanish colonization of California, it is estimated that there were at least 130,000 Indians in California, although this figure has been placed as high as 700,000. Even at the low estimate, California had about 16% of the indigenous population of the United States by comparison with 5% of its land area, thus making California perhaps the most densely populated area of what became the United States.

The indigenous peoples of Southern California comprised several tribal groups, who from north to south are:

–The Chumash, occupying three of the Santa Barbara or Channel Islands, and the coastal region of Santa Barbara.

–The Serrano located in the San Bernardino Mountains and the lowlands of the San Bernardino Valley.

–The Gabrieleno, which have also been called Tongva, but the tribal members I’ve met prefer the name Kizh, occupied Los Angeles County, half of Orange County (including Fullerton), and two of the Channel Islands (Santa Catalina and San Clemente).

–The Juaneno (although they prefer the name Acjachemen) who live south of what is known as Aliso Creek and north of the Las Pulgas Canyon in what are now the southern areas of Orange County and the northwestern areas of San Diego County.

–The Luiseno who prefer the name Payómkawichum, live in the present-day southern part of Los Angeles County to the northern part of San Diego County, and inland 30 miles.

–The Cahuilla who live in the inland basin between the San Bernardino Mountains and Mt. San Jacinto.

–The Digueno, who prefer the name Kumeyaay live in a territory bounded on the west by the ocean, on the north by the country of the Luiseno and the Cahuilla.

Beginning with San Diego in 1769, Missions were established on all the tribal lands of these peoples.

The Effects of Missionization

Spanish colonization of California began in 1769, with the establishment of Missions, pueblos (towns), and presidios (military forts). This led to an alarming population collapse for the native people of Southern California.

“From a total of 30,000 in 1769, the number of Indians in Southern California declined to approximately 1,250 by 1910,” McWilliams writes, “the survival of Indians was in inverse ratio to their contact with the Missions. So far as the Indian was concerned, contact with the Missions meant death.”

Allow me to include a lengthy quote from McWilliams:

“With the best theological intentions in the world, the Franciscan padres eliminated Indians with the effectiveness of Nazis operating concentration camps. From 1776 to 1834, they baptized 4,404 Indians in the Mission San Juan Capistrano and buried 3,227…In not a single Mission did the number of Indian births equal the number of Indian deaths. During the entire period of Mission rule, from 1769 to 1834, the Franciscans baptized 53,600 adult Indians and buried 37,000. The mortality rates were so high that the Missions were constantly dependent upon new conversions to maintain the neophyte population which never, at any period, exceeded the peak figure of 20,300, reached in 1805. So far as the Indians were concerned, the chain of Missions along the coast might best be described as a series of picturesque charnel houses. For it was the Mission experience, rather than any contact with Spanish culture, that produced this frightful toll of Indian life.”

What led to this calamitous population decline? One result of removing indigenous people from their tribal lifeways and herding them into cramped Mission compounds was a devastating spread of disease for which the people had no natural immunity.

“From 1769 to 1833, 29,100 Indian births were recorded in the Missions of California, and 62,000 deaths, the excess of deaths over births being 33,500,” McWilliams writes. “Of this decline, Dr. Sherburne F. Cook estimates that 15,250 or 45% of of the population decrease was caused by disease. Two epidemics of the measles, one in 1806 and the other in 1828, took a heavy toll of neophyte lives. Within the first decade of Mission rule, syphilis appeared throughout the province. Despite the injunctions of officers and priests, the scrofulous Spanish soldiery spread the disease among both the gentile and neophyte Indian women.”

In the Missions, “the sanitation was wretched and the diet inadequate. From 1776 to 1825, there was only one qualified physician in all Alta California.”

“Once the Indians were assembled in large numbers in the Missions, they had to be strictly regimented and the problem of discipline immediately became a serious one,” McWilliams writes. “From the moment of conversion, the neophyte became a slave; he belonged thereafter to the particular Mission.”

As disease decimated native populations, their treatment in the missions accelerated their physical and cultural decline.

“If the Indian would not work,” writes C.D. Willard, “he was starved and flogged. If he ran away he was pursued and brought back.”

“If a neophyte deserted from one Mission to another, he was immediately arrested, flogged, and kept in irons until he could be returned to the Mission to which he belonged, where, on arrival, he was again flogged,” writes McWilliams.

Contrary to the popular mission myth of kindly padres, the historical record paints a far more disturbing picture.

“Numerous instances were recorded of floggings of fifty to a hundred lashes. Fetters, shackles, and the stocks were commonly used as disciplinary measures,” McWilliams writes. “Referring to Father Zalvida of the Mission San Gabriel, Hugo Reid wrote that ‘he must assuredly have considered whipping as meat and drink to the Indians, for they had it morning, noon, and night.’”

Because of this mistreatment, many native people tried to escape the Missions. In response, “large-scale military expeditions had to be organized to round up the escaped neophytes.”

Regarding their diet, “the neophytes were kept in a state of chronic undernourishment in order to retard the tendency to fugitism.” According to Cook, “the Indians as a whole lived continuously on the verge of clinical deficiency.” The work-day was from six in the morning until almost sunset.

The native people resisted this devastation through occasional revolt, attempted escapes, and increased rates of abortion and infanticide.

“So prevalent was the practice of abortion,” McWilliams writes, “that miscarriages were punished as criminal offenses. The penalty prescribed by Father Zalvida for the Indian woman who had suffered a miscarriage consisted in ‘shaving the head, flogging for fifteen subsequent days, iron on the feet for three months, and having the appear every Sunday in church, on the steps leading up to the altar, with a hideous painted wooden child in her arms.’”

The Missions also failed in achieving the theoretical goal of “educating” the native peoples.

“The padres,” wrote J.M. Guinn, “were opposed to educating the natives for the same reason that southern slaveholders were opposed to educating the Negro, namely, that an ignorant people were more easily kept in subjection.”

The effect of the imposition of Catholic Christianity on the native people was a cultural genocide–an alaming decline in indigenous beliefs and practices.

From the Franciscan point of view, as Dr. Cook points out, it was “vitally necessary to extirpate those individual beliefs and tribal customs which in any way whatever conflicted with the Christian religion.”

Alfred Robinson wrote that “it is not unusual to see numbers of Indians driven along by the alcaldes, and under the whip’s lash forced to the very door of the sanctuary.”

To read more about the dark side of the California Missions, check out my book report on Elias Castillo’s book A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions.

Secularization of the Missions (1834-1843)

Beginning in 1813 and continuing through the 1830s was the process of secularization of the Missions–that is, transferring them from church to civil government rule. This also coincided with the independence of Mexico from Spain. Beginning in 1821, California was no longer a part of Spain, but rather a province of Mexico.

“Under the Spanish scheme of colonization, the Missions were never intended as permanent settlements. As originally planned, each Mission was to be converted into a civil community within a decade after its establishment, by which time, so it was reasoned, the tutelage of the Indians would have been completed,” McWilliams writes. “The Franciscans did not hold title to the Mission lands as grants from the Crown; they merely enjoyed a right of use and occupancy at the pleasure of the government. Theoretically they were trustees for the Indian neophytes, upon whom title to the Mission lands and properties was eventually to devolve.”

Unfortunately the plan to turn Mission lands over to the Native peoples never really materialized.

“By 1834, however, the Missions had become too exceedingly rich, their lands and holdings being valued at $78,000,000,” McWilliams writes. “At the peak of its activities, the Mission San Gabriel, for example, operated 17 extensive ranchos and owned 3,000 Indians, 105,000 head of cattle, 20,000 horses, and 40,000 sheep. The pressure to plunder these estates soon became much stronger than the capacity or willingness of the weak Mexican government to enforce the secularization decrees. As a consequence, the laudable scheme of secularization degenerated into a mad scramble to loot the Missions. Faced with the possibility of war with the United States, Governor Micheltorana ordered the disposal of the remaining Mission properties in 1844, by which time all semblance of adherence to the plan of secularization had been abandoned.”

Thus began the “rancho” period of Southern California history, when the land was no longer controlled by the church, but rather by an elite group of people who were granted large tracts of land which became sprawling ranchos.

“From 1769 to 1822, the Spanish had made only about twenty large land grants in the province, but, in the period from 1833 to 1846, over 500 large grants were handed out,” McWilliams writes. “As the threat of American intervention became increasingly imminent, the provincial governors showered their favorites with princely grants. Many of these large land grants were carved out of properties expropriated from the Missions or from the ranches operated by the Missions. In many cases, they were stocked with horses, sheep, and cattle purchased from the Missions or simply appropriated at the time of secularization.”

Under the Mexican “rancho” system, the native peoples continued to work primarily as a labor force, but in a slightly different way. The labor system of the ranchos was essentially the hacienda system of Mexico.

“Paid a fathom of black, red, and white glass beads for a season’s work, these Indian peons were, as Don Juan Bandini said, ‘the working arms which made it possible to carry out agricultural and other projects and to provide necessities.’”

“During the period of secularization, the Indian population of California declined from 83,000 to 72,000, a decline of about 700 a year by comparison with a decline of about 900 a year during the Mission period,” McWilliams writes.

The American Conquest

From 1846 to 1848, the United States waged an expansionist war against the Republic of Mexico, which resulted in the U.S. acquiring nearly half of Mexico, including California.

“While much of the damage to Indian life had been caused prior to the American conquest, still the relative impact of Anglo settlement was about three times as severe as that of Spanish and Mexican settlement,” McWilliams writes. “At the time of the conquest, there were still about 72,000 Indians in California, including the remnants of the neophyte or Mission Indians. By 1865 the total had been reduced to 23,000, and by 1880 to 15,000.”

“Indian life,” wrote Stephen Powers in a government report of 1877, “burst into air by the suddenness and fierceness of the attack…Never before in history has a people been swept away with such terrible swiftness.”

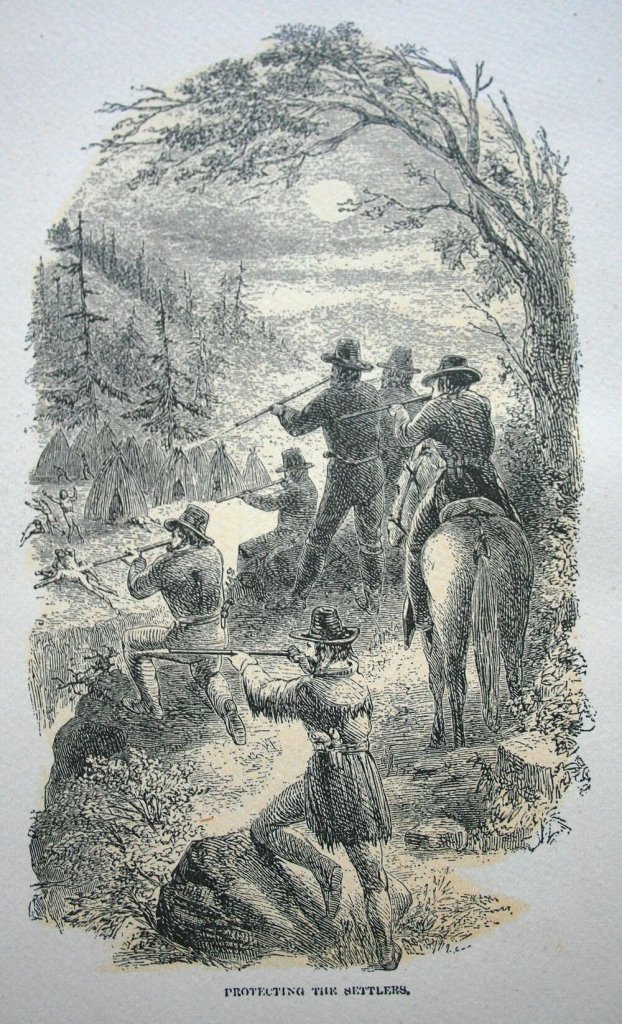

“American settlers came to California with two centuries of Indian warfare behind them. The Indian had no rights the white man was bound to respect. If the Americans had a policy, it was to extirpate Indian culture, not to transform it,” McWilliams writes.

The American settlers “drove the Indians from their fisheries and acorn groves, destroying the supply of fish by muddying and polluting the rivers and creeks, and, in raids on Indian villages, destroyed food supplies which had been laboriously accumulated,” McWilliams writes.

In addition to gold, the Americans wanted land and would often use physical violence against the native population. “In less than two years after its establishment, the new state of California had incurred an indebtedness of over one million dollars in fighting Indians. It is estimated that, in about a hundred Indian ‘affairs,’ or raids, some 15,000 Indians were killed in the period from 1848 to 1865.”

After California became a U.S. state, laws were enacted which essentially kept the native population at the lowest rung of society. Native people were not allowed to testify in court, they could be declared “vagrants” on the petition of a white person, and a law “established a system of ‘indentured apprentices,’ under which minors, with the ‘consent’ of their parents, might be farmed out as apprentices for a term of years.”

“An Indian could be shot for any minor infraction of the white code, such as speaking out of turn, getting in the way, or demanding payment of wages,” McWilliams writes. “The indentured apprentice law merely rationalized the old Spanish custom of kidnapping Indian children as peons. Between 1852 and 1867, Dr. Cook estimates that 4,000 Indian children were taken from their parents and apprenticed to various employers under this statute.”

To read more about how native Californians fared under American rule, check out my article “The California Native American Genocide.”

Leave a comment