The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

Anthony Ondaro (of Brea) was interviewed in 1971 by Sonia Eagle Dias for the CSUF Oral History program. Here’s what I learned from reading this interview, with some historical context provided by the excellent web site Basques in California.

Ondaro was born in 1897 Elantxobe, in the Basque country of Spain. He immigrated to the United States in 1908 when he was 11 years old. After spending some time in Washington state, Ondaro came to work on the Bastanchury Ranch in Fullerton, mostly driving mule teams.

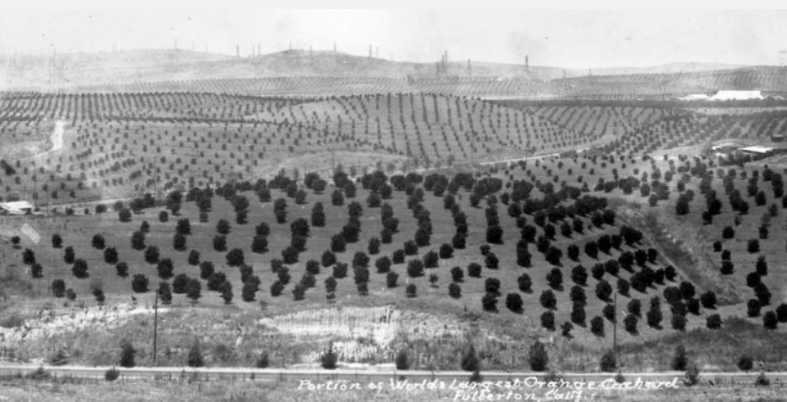

After he got married, he moved for a while to Corona, but then came back to the ranch in 1926, when the Bastanchurys were expanding their citrus planting into what would become the largest orange grove in the world.

The ranch had a boardinghouse, where a lot of men lived, as well as worker camps throughout, each with a foreman. The foreman would get a house and some acres on the property.

There were American, Basque, French, Spanish, and Mexican workers on the ranch, although the vast majority of the workers were Mexican.

When Ondaro worked on the ranch, the majority of the plowing, digging, and irrigating work was done without tractors–with mule and horse teams.

Ondaro remembers three large Mexican picker camps–one where the Fullerton Golf Course, one by Laguna Lake, and “another one down by the lower part of the ranch, close to the Santa Fe Railroad.”

When asked what the Mexican camps were like, Ondaro said, “mostly it was little houses built by themselves.”

He remembers that the Mexicans in the camps used to celebrate the sixteenth of September (Mexican Independence Day) and Cinco de Mayo with fiestas and dancing.

There was a Mexican school on the Bastanchury ranch where teachers taught for the Americanization program.

Click HERE to read more about Mexican citrus worker villages in Fullerton and Orange County.

Wine and recreation…

Even during Prohibition, the Bastanchurys used to make their own wine in large barrels.

“Prohibition days…They never bothered us, long as you made it for your own use, they never bothered you,” Ondaro remembers.

The Basques of southern California used to gather for picnics and handball games at the Bastanchury ranch.

“Older people, they used to have a great, big table, with sort of a ramada, with palm leaves on top,” Ondaro remembers. “They used to sit there and play cards all afternoon, drink wine or drink beer.”

On getting screwed over oil…

Ondaro remembers a significant lawsuit that the Bastanchurys filed against an oil company. Apparently, the company drilled a well that showed oil, but then covered it up and lied to the Bastanchurys about the find. Convinced the land was not worth much, the family sold.

“They told them there was no oil there but the oil was there,” he remembers. “The drillers and the roustabouts, the guys that worked in the well, they knew there was oil there.”

Gaston Bastanchury got the men who had worked the well to testify that there was oil. And he won the case.

Unfortunately, even though they won the lawsuit, they still got the short end of the stick because they took a cash settlement, instead of getting royalties on mineral rights.

The story is told in more detail in an article from the web site Basques in California:

In 1903, the Murphy Oil Company leased the West Coyote Hills lands from the Bastanchury Ranch to dig for oil. One year of excavations found them hot mineral water at 3,000 feet. As one of the oil workers later confessed, they found an oil well at 3,200 feet but covered it up. In 1905, Murphy bought off from Domingo Bastanchury more than 2,200 acres in the surroundings of La Habra, at $25 an acre. Allegedly, Murphy assured Domingo before the acquisition, that those lands held no oil. Time later, the Los Coyotes Hills area became South California’s largest oil field.

As soon as the Bastanchurys understood it had all been a swindle, they sued Murphy Oil Company for several million dollars. The family was only compensated $1.2 million dollars, and most of it went to attorney fees. Time would show that, sadly, the Bastanchurys further were shortchanged by the settlement: if they had instead asked for royalties on the oil fields that had multiplied around them, they would have generated a larger profit. Probably, the Bastanchury family would have been in better shape then, when the Great Depression hit in 1929.

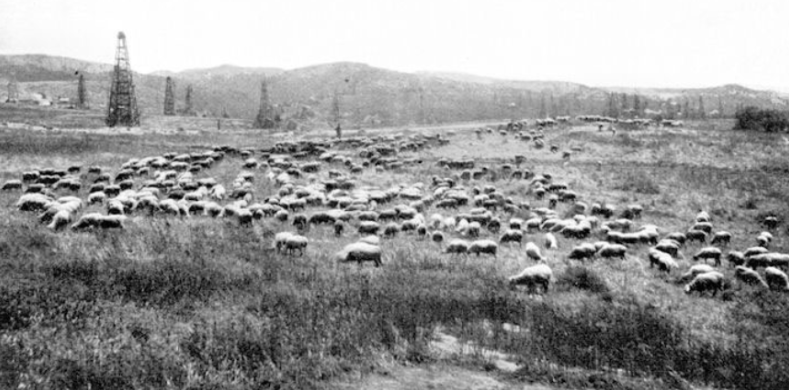

Ondaro remembers an old foreman named Jean Bacay telling him that when he used to herd sheep, there were occasional oil deposits on the ground and sheep would sometimes get stuck in them.

He told me many a time, he said, “Look now.” He says, “Gold in the ground and we used to cuss it everytime we looked at it because we used to lose a sheep or two every once in a while there.”

St. Mary’s Church…

According to Ondaro, Mrs. Bastanchury gave the money and the property to build the original St. Mary’s Catholic church in Fullerton. He says they actually named the church after her, as her name was Maria (Mary).

In 1923 or 24, the church property was sold, and new property was purchased, which is the present location of the church. Mrs. Bastanchury was not happy.

On the expansion into citrus…

The family patriarch Domingo Bastanchury first established the ranch in the mid to late 1800s for sheep grazing. Domingo passed away in 1909 and the management of the ranch fell to his wife and sons.

From Basques in California:

The Bastanchurys started their citrus orchards on their 2,500-acre estate in 1914. In 1926, their citrus venture expanded when the Bastanchury Ranch Company leased 2,000 acres from the Union Oil Company. While the trees were still young, they grew tomatoes in between rows. Rather than being next to each other, the orchards were spreaded out from the La Habra Heights to Fullerton-Brea, all the way to Olinda.

The Bastanchury Ranch leased another 500 acres from Times Mirror Company in the east part of Salton Sea in Imperial County, to grow oranges and lemons. By 1933, the ranch owned a total of 5,000 acres’ worth of citrus and tomato orchards. It was the world’s largest orange grove owned by a single proprietor.

The Bastanchurys had their own packinghouses, and the railroad ran lines directly to into the ranch.

They also established their own brand, Basque brand, which fetched premium prices.

Unfortunately. According to Ondaro, the Great Depression proved disastrous to the Bastanchurys.

“They had a lot of fruit but it didn’t bring any money…There was no return,” Ondaro remembers.

Unable to honor their debts and agreements with Union Oil and the Times Mirror Company, the ranch went into bankruptcy.

“I was a foreman at the time and then after 1932 is when the trustee and bankruptcy came in. There was a man appointed by the court. He was in charge of it.”

1932 was also the year that nearly all of the Mexican workers on the ranch were “repatriated.”

The Bastanchury sons got almost nothing in the bankruptcy, although Mrs. Bastanchury managed to hold onto a smaller ranch.

On the Bastanchury sons…

Ondaro has interesting memories of the four Bastanchury sons: Dominic, Gaston, Joe, and Johnny.

After the bankruptcy, Gaston moved to Nebraska, where he worked as a mining engineer.

According to Ondaro, Johnny “was the most worthless guy of all of them…The only thing he used to do is just go to Paris and France and spend fifty thousand, a hundred thousand dollars whenever he pleased. He had a family, a nice family, too. A real nice wife…But he’d just go with all the women around this way and that way. I mean, the guy didn’t have no purpose in life.”

Joe “used to drink quite a bit” but he “did more than Johnny.” Joe was married to Juanita, who was also interviewed about her recollections of the Bastanchury Ranch.

Dominic, the eldest, had four hundred acres of his own where he raised hogs and walnuts.

According to Ondaro, Dominic was an illegitimate child of Maria and a manager of the Union Bank in Los Angeles.

“The manger of the Union Bank was the one that really was the father of Domingo [Dominic]…while she was in school.”

On the decline of citrus…

Ondaro discusses factors that led to the decline of citrus, including a disease called quick decline, and the subdivisions that went in after the population/housing boom after World War II.

Today, the Bastanchurys are remembered in Fullerton by Bastanchury Road, Bastanchury Park, and Basque Ave.

Leave a comment