The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

In 1896, Homer Plessy, who was 1/8th black, entered a whites-only railroad car in New Orleans and was arrested. The Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that the doctrine of “Separate but equal” was constitutional; as long as equal facilities were provided for different races, it was “fair.” Justice John Marshall Harlan was the one dissenting vote and wrote, “The Constitution is colorblind.”

This “separate but equal” doctrine stood for 50 years until in the case of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the Supreme Court overturned the Plessy decision saying, “Separate is inherently unequal.” In the majority opinion, they quoted Justice Harlan.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a significant chapter of Fullerton’s civil rights story centered around how to desegregate Maple Elementary School, which was 98% Latino and Black at the time.

Officially, segregation of African American students in California was outlawed by the State Supreme Court in 1890, and the segregation of Mexican-American students succumbed to a legal challenge by a group of parents in Orange County in the case Mendez v. Westminster in 1947. And in 1954, the Brown decision case declared that the “separate but equal” doctrine was unconstitutional.

However, while de jure (legal) segregation was made illegal, de facto (in practice) segregation remained. Neighborhoods were still separated by patterns of historic housing discrimination–so schools remained segregated.

The integration plan many districts came up with was to bus students to schools outside their (de facto segregated) neighborhoods.

While many in the north were ideologically opposed to segregated schools, many white parents were also opposed to having their kids bused from their neighborhood schools to schools in black and Latino neighborhoods.

Thus it was often the case that, in order to comply with desegregation orders, districts would adopt one-way busing, in which they would bus black and Latino kids to majority white schools, but not bus white kids to majority black and Latino schools.

A fairer, but often dismissed, proposal was two-way busing, in which the busing would be reciprocal—with some white kids going to majority black and Latino Schools, and some black and Latino kids going to majority white schools.

In his 2016 book Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation, historian Matthew F. Delmont chronicles this oft-forgotten aspect of the American Civil Rights story—when millions of Americans decided the limits of desegregation.

A few examples:

• New York: In March 1964, over 10,000 white parents walked from the Board of Education building in Brooklyn to city hall in Manhattan to protest against integration of New York City schools. They hoped to persuade the school board to abandon a school pairing plan that called for students to be transferred between predominantly black and Puerto Rican schools and white schools.

• Chicago: In 1967, superintendent Redmond proposed a plan to bus 5,000 black and white students between the South Shore and Austin areas. After white protests, this two-way plan was discarded in favor of a one-way plan.

• Boston: In 1966, Boston implemented a one-way busing program called METCO. Suburban communities welcomed a small number of black students from Boston city schools through the METCO program, but opposed two-way “busing” (that is, sending suburban kids to Boston city schools and vice versa).

In March 1972, President Richard Nixon delivered a nationally-televised speech in which he called on Congress to enact a moratorium on orders mandating that school districts use busing of students to achieve school desegregation.

While Brown v. Board of Education may have established the legal mandate that “separate but equal” schools are unconstitutional, actual implementation of integrating schools took much longer and in some places never really happened.

Two important court cases in California in 1963, Crawford v. Los Angeles School Board and Jackson v. Pasadena City School District prompted the State Board of Education to adopt an advisory policy “declaring that any school whose enrollment of minority students differed by more than 15% from the percentage of students in the district as a whole would be considered racially imbalanced and would require the school district to take corrective action.”

As a result of these cases and State orders, Fullerton began the process of desegregating Maple School.

Fullerton resident Roberto “Bobby” Melendez was among the first students to be bused from Maple to one of eight other schools to begin the desegregation process during the 1966-67 school year when 5th and 6th graders were bused. Bobby was going into sixth grade. He, along with a number of friends from Maple, was bused to Acacia school.

“I think we were more of a curiosity to the kids that were there because they were like social distancing from us,” Melendez said in an interview with the Fullerton Observer. “They were kind of looking at us with some surprise.”

Fortunately, he knew some boys from Acacia from playing East Fullerton Little League, like his friend Kevin Barlow.

“So we went up to Kevin and his friends during recess and said, ‘Lets play some football.’ So we all played that day…It was the browns against the whites,” Melendez said.

When the bell rang, Kevin walked up to Bobby and said, “Tomorrow I’ll be on your team.”

Thus began the integration of Acacia school—not with federal troops, but with a game of schoolyard football.

“I think that set the stage,” Melendez said. “We became very good friends. I got to stay over at some of the houses of some of my new friends that I met.”

Bobby was fortunate in having a group that bonded over sports. While at Acacia, he remembers noticing a difference in the quality of the books and facilities between Maple and Acacia.

Fullerton resident Mary Perkins, who is African American, said that her son and daughter were also among the first students to be bused from Maple for integration. They too were bused to Acacia.

“When my son was at Acacia, he was the only black student in the whole student body,” Mary said in an interview with the Observer. “My daughter [one grade behind her brother] did have one other girl there [who was] African American. They were not kind to them, you know. They told them, ‘My mother says I have to be nice to you because you’re poor.’ That kind of stuff.”

Mary and her husband Gil moved to Fullerton in 1960 with their two children.

“We were looking for a place for the kids to go to school where they could get all their education in one place, so we decided on Fullerton,” Mary said.

While Fullerton “the Education City” offered many educational opportunities, housing options were limited for African Americans at that time.

“We looked for a house in a lot of places, but they [realtors] would only show us two tracts when we were looking for a house. One was here [on Truslow] and one was in Placentia,” Mary said.

Gil Perkins involved himself in fair housing and often spoke at City Council meetings on behalf of his neighborhood.

As 1970 rolled around, all 12 Orange County school districts were ordered by the State to rectify their racially imbalanced enrollments. Although the Fullerton School District had begun busing 5th and 6th graders out of the Maple neighborhood for the past few years, the State ordered that Maple could not have more than a 30% minority enrollment.

Maple at the time had a 98% Latino and black enrollment.

The LA Times wrote, “Although Maple School is the only one in Fullerton identified as imbalanced, it has perhaps the most seriously lopsided classrooms in all of Orange County.”

A Human Relations Advisory Committee was formed in 1971 to develop integration plans for Maple. They all involved voluntary two-way busing.

Judith Kaluzny was part of this committee, which developed three integration plans, all of which called for voluntary two-way busing of students between Maple and other schools, and keeping Maple open. Unfortunately, according to Kaluzny, the administration was determined to close Maple school.

“Our plans were summarily dismissed,” Kaluzny remembers. “We were supposed to have eliminated segregation in our elementary schools by eliminating the segregated school.”

After basically discarding the plans created by the Human Relations Committee, the FSD administration then created its own desegregation plans, which involved closing down Maple entirely. All involved one-way busing of kids out of the Maple neighborhood.

Dr. Richard Ramirez, who grew up in the Maple neighborhood, was a sociology professor at Fullerton College in 1972. He got involved with the Maple Community group because he felt that the families in the neighborhood were not being treated fairly by the school administration and the community at large.

“The burden of busing was put on just one segment of the community—those that had the least collective voice,” Ramirez said. “The Board did not reflect that segment of the community.”

Ramirez was instrumental in helping formulate the Maple Community’s own desegregation plan, which called for two-way busing and other measures to achieve equity.

Part of his role was to meet with parents in north Fullerton to better understand their concerns.

“I’d say we had 10 to 15 different small family group meetings with them,” Ramirez said. “The common theme that came out of our discussions with them was they were fearful for their kids because they would be going into the ‘barrio,’ the ‘ghetto.’”

The other main concern of the largely white parents of north Fullerton was the quality of education at Maple.

“Those were the two consistent themes—fear and anxiety as far as the quality of education at Maple, and the simple fact that they just didn’t want their kids to mix with the brown kids,” Ramirez said.

At a crowded school board meeting in January 1972, Ramirez and the Maple community presented their plan for desegregation, which involved keeping Maple open and implementing two-way busing between north and south Fullerton.

Among the numerous speakers at that meeting was Florine Yoder who said she represented the residents of north Fullerton. According to the Fullerton News Tribune, which chronicled many of these meetings for posterity, “Yoder told the board that if minorities wanted to attend a desegregated school, they must accept the responsibilities of desegregation, including busing and attending a school out of their neighborhood.”

Evidently, the responsibility of desegregation did not extend to those predominantly white families in north Fullerton.

“We do not want our children bused and we want to retain schools in our own neighborhoods,” Yoder told the board.

Reflecting on those meetings, Ramirez said, “It was really a question of fairness. If indeed we have to follow this federal law, then every family, every child should be able to give the same level of responsibility.”

The following week, 200 Fullerton residents showed up at another school board meeting to discuss the seven different desegregation plans—three from the Human Relations Committee, three from the administration, and one from the Maple Community.

“We want meaningful education, not useless transportation,” said Layton R. Buckner, spokesman for the Concerned Parents and Citizens of Sunset Lane School [in north Fullerton]. “We feel it is wiser to spend money on teachers, books, and special programs than on buses and bus drivers.”

Some Latinos, like Larry Labrado, were also against busing.

“Chicanos don’t want to go to your schools,” he said. “We want better education at our school.”

The News-Tribune reported, “Any discussion of the specifics of the seven plans was lost in the attacks on busing and the laws that require desegregation.”

In February 1972, over 500 people packed into Wilshire Auditorium to voice their opinions on the question of Maple School. At the meeting, police in riot gear were on hand to ensure an orderly proceeding.

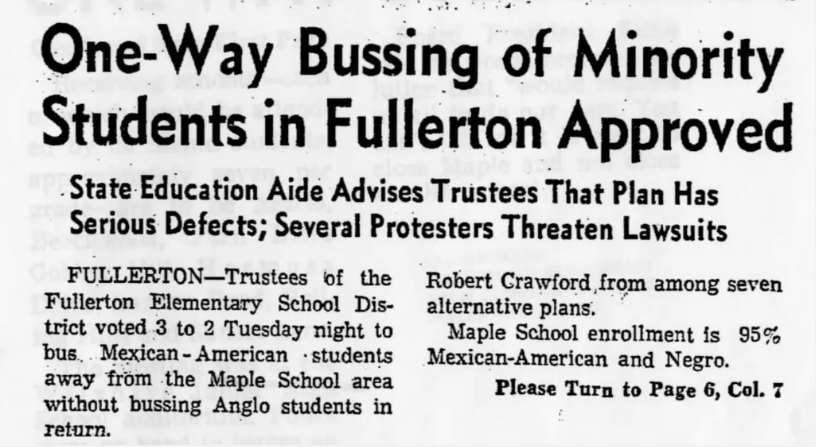

After lively public debate, the School Board voted 3-2 to adopt a desegregation plan that closed Maple School and called for the busing of all children from the Maple neighborhood to eight other schools.

Board members Alvin M. Berlowe, Nancy Fix, and Steward L. Johnson voted in favor. Board president Robert F. Rube and Lloyd G. Carnahan voted against.

As was documented in the Fullerton News-Tribune, Board President Rube said, “You can’t tell me it’s right to close Maple and not close other schools.”

“The inequity of placing the main burden of desegregation on the minority community was a common theme during the hour and 20 minute discussion period preceding the vote,” according to the News-Tribune.

“Why are we putting on the backs of the minority the responsibility of integrating the schools?” asked Bruce Johnson. He called for a “new advisory committee that will not be disbanded until an equitable and just solution is found.”

Upon completion of the vote, Barney Schur, consultant in intergroup relations for the California Department of Education said, “You are going to have a problem with it [one-way busing]. It is viewed as unconstitutional by the courts.”

According to the News-Tribune, “Upon hearing the vote, several representatives of the largely Chicano Maple community threatened lawsuits on the basis of discrimination.”

Lopez v. Trustees of the Fullerton Elementary School District

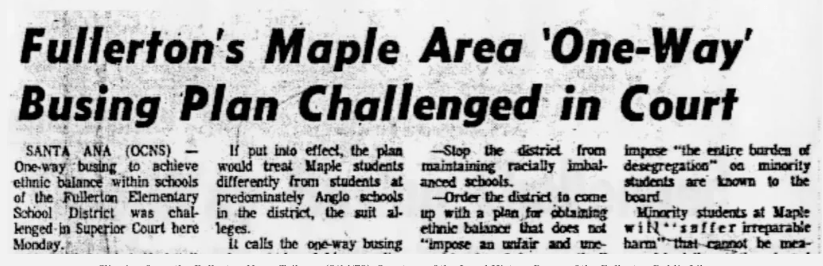

Following the February 1972 school board decision to close Maple school, families from the neighborhood filed a lawsuit against the District, alleging that the desegregation plan violated the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution as well as State desegregation laws.

The lawsuit called the closing of Maple School and the one-way busing plan “invidious discrimination” that “imposes the entire burden of desegregation on minority students.”

The lawsuit had the support of the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund, the Orange County Legal Aid Society, the Western Center of Law and Poverty, and the federal office of Economic Opportunity.

Lopez v. Trustees of the Fullerton Elementary School District was filed on behalf of “all Spanish surnamed and Negro students attending Maple School.”

During the trial, which took place in late June and early July 1972, Orange County Superior Court Judge William C. Speirs asked, “Is one-way busing the best way to comply with the law? Or is it just a means of avoiding two-way busing?”

Morris Schneider, a consultant in intergroup relations for the State Department of Education “testified that one-directional busing away from closed schools, rather than reciprocal busing, is being done in Redlands, Palm Springs, Corona, Riverside, and San Bernardino,” according to the LA Times.

Schneider said the Fullerton school board’s plan “meets the requirements of the law.”

Under cross-examination by Joe Ortega from the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund, “Schneider admitted that only Mexican American and Negro schools have been closed in districts where it has been necessary to adopt plans for achieving ethnic balance,” according to the LA Times.

“Isn’t it true, Mr. Schneider, that to your knowledge only Chicano and Black schools have been closed and their students forced to participate in one-way busing?” Ortega asked.

“Yes, as far as I know, that is true,” Schneider said.

Fullerton School District Superintendent Robert Crawford also acknowledged that two-way busing “is not prohibitively costly,” which contradicted statements that were often made at school board meetings when presenting the various integration plans.

On July 3, 1972, Judge Speirs upheld the Fullerton School District’s plan to close Maple School and bus all the children from the neighborhood to other schools in the district.

“Judge Speirs ruled that busing students from Maple School, with 85% Mexican American and 10% Black enrollment, without busing students from predominantly Anglo schools is ‘not racially discriminatory,’” according to the July 4, 1972 LA Times.

“Attorney Joe Ortega of the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund said some members of the Chicano community ‘will be very bitter,’ and ‘some will do their best to live with it and get their children to schools,” according to the LA Times.

Thus, beginning in September 1972, Maple School was closed as an elementary school and all its students were bused to other schools in the district.

According to the Fullerton News-Tribune, “The Maple School will house an expanded preschool, a community cultural center, and will be the site of a Community Open School, an alternative mini school this fall on a pilot basis.”

Reflecting on the impact of closing Maple School, long time Fullerton resident Vivien Jaramillo told The Observer in an interview, “It splits you up so much out of your element that you don’t have any tight bonds with anybody in the neighborhood because they’re all going different places. That part was kind of a bummer, and it was still affecting my kids when they were growing up.”

Retired Fullerton College sociology professor Richard Ramirez, who was involved in formulating the Maple Community’s own desegregation plan (which was not adopted), told The Observer in an interview, “It’s best categorized as institutional racism.”

Proposition 21 (The Wakefield Amendment)

In 1972, the same year that the Fullerton School District Board of Trustees voted to close Maple School and bus all of its students to other schools for the purpose of desegregation, voters in California passed Proposition 21, which banned school districts from using race to assign students to schools for desegregation.

In his book Racial Propositions: Ballot Initiatives and the Making of Postwar California, historian Daniel Martinez Hosang writes that the sponsor of Prop 21, Floyd Wakefield, was “a fiery conservative from the Los Angeles suburb of South Gate…[who] railed against the yoke of ‘forced integration’ and sounded a thinly-veiled call to defend white rights and ‘freedom of association.’”

Prop 21 passed with a 63% majority in 1972.

Following its passage, the NAACP and the ACLU filed lawsuits to overturn the measure and in 1975, “the State Supreme Court found that it violated the state and federal constitutions and involved the “state in racial discrimination.”

Hosang writes that although Prop 21 was only in effect for two years, it “did have a chilling effect on many local school desegregation efforts. In early 1974, the State census revealed that 192,000 more students attended segregated schools in comparison to 5 years earlier.”

Because Maple had been closed prior to the passage of Prop 21, it remained closed for 25 years.

Although Maple was closed as a k-6 elementary school in 1972, it remained open as a preschool, a community center, and a newly-created experimental “Community Open School.”

Judith Kaluzny, who had been on the Human Relations Committee that had developed integration plans for Maple that were dismissed by the District, was instrumental in establishing the Community Open School at Maple, which opened in fall of 1972.

“Arriving at Maple School with my VW busload of kids that first day of school, I was abashed,” Kaluzny remembers. “Mothers were standing on curbs waiting with their children to be bused to other neighborhood schools, while I and others were busing our children to their neighborhood school [Maple]. What a nasty choice the District had handed us. And I think they did so in order to keep us liberals busy and away from participating in the political consequences of closing Maple School.”

The Maple Game

The following year (1973), local civil rights activists Ralph Kennedy (who would go on to co-found The Fullerton Observer in 1978) and Kay Wickett hosted two seminars at the local YWCA to play what they called “The Maple Game.”

The seminars were a part of the national Project Understanding formed in 1969—a group of churches with the goal of eliminating racism, which they defined as “anything which works to the advantage of whites and the same time to the disadvantage of ethnic minorities, whether it’s intentional or unintentional, conscious or unconscious, personal or institutional,” Wicket told the LA Times.

In the Maple Game, attendees took on the roles of different people and groups involved in the Maple desegregation controversy.

Some were members of the Maple Neighborhood Council advocating for two-way busing, others were members of The Concerned Parents and Citizens of Sunset Lane School, still others were members of the School Board and administration.

“When [the game] was all over, a member of the ‘elementary school administration’ had been fired for stating the root of the problem lies in the institutional racism that exists within the teaching system,” the LA Times reported in an article called “Maple Game Tests Fullerton Racism.”

The article begins, “Despite the seeming quiet of this upper middle class community, it seems there are problems of prejudice here, according to that recent gathering, although it is not the blatant kind of racism you’re likely to find in larger cities.”

The purpose of this role-playing game, according to Kennedy, “was to raise individuals’ levels of consciousness about the frustrations involved in solving a problem like the desegregation of the Maple School, problems that end up exposing hidden nerve endings, tapping concealed emotions about the existence or nonexistence of prejudice.”

“Nobody’s Complaining”

Even though Prop 21 was declared unconstitutional in 1975, it still erased the State’s integration guidelines and thus had a lasting impact.

A 1977 LA Times article entitled “Integration in County: Nobody’s Complaining” gives a bleak assessment of Orange County School desegregation efforts at that time.

“Information on the current status of integration in the county’s schools cannot be obtained from the local chapters of the League of Women Voters, the NAACP, or the Orange County Human Relations Commission,” the article states.

“In any case, neither the State nor the federal government has staff enough to monitor the status of school integration very closely,” the LA Times states. “At the State Department of Education, the task of counseling school districts on desegregation has been relegated to one man—Ted Neff of the State Bureau of Intergroup Relations.”

“Now that the Bureau’s role is purely advisory,” Neff said. “It is hardly ever consulted by school districts.”

By the late 1970s, local, state, and federal governments had largely abandoned active measures to desegregate schools.

In 1979, another ballot measure in California (Prop 1) would sound the death knell of school integration in the Golden State.

Prop 1: The Robbins Amendment

Part 3 of this series addressed Prop 21, which passed in 1972 and sought to end the practice of busing kids to desegregate schools in California. Prop 21 was championed by a fiery conservative from Los Angeles named Floyd Wakefield who railed against the yoke of “forced integration.”

Although a majority of voters favored it, Prop 21 was declared unconstitutional in 1975 (it violated the equal protection clause of the 14th amendment), but it did have a chilling effect on state desegregation efforts.

Wakefield’s successor in the fight against busing to achieve desegregation was, interestingly, not another conservative Republican, but a liberal Democrat from the San Fernando Valley named Alan Robbins. Robbins had supported the Equal Rights Amendment (for women) and supported the United Farm Workers.

Robbins learned from the legal shortcomings of Prop 21 and carefully crafted an initiative in 1979 (Prop 1) that would stand up to constitutional and legal challenges. The Robbins Amendment, like the Wakefield Amendment, sought to end mandatory busing of students to achieve integration in California.

“The Robbins Amendment sought to amend the California State Equal Protection Clause by stating that as long as the US Supreme Court interpreted the 14th Amendment as only prohibiting de jure (legally mandated, as opposed to de facto—in practice—segregation), California courts would have to do the same,” historian Daniel Martinez Hosang writes.

“Calls among busing opponents for the protection of ‘majority rights’ quickly waned in favor of arguments that represented the interests of ‘all children,’” Hosang writes.

But the burden of desegregation did not fall equally on “all children.”

Both Prop 21 in 1972 and Prop 1 in 1979 are significant to the Maple School story because they give the broader context of widespread opposition to busing kids as a means to achieve school integration, and the disproportionate impact this had on students of color.

Because Maple school had been closed, students from that predominantly Latino and Black neighborhood continued to be bused.

The 1972 Maple “solution” reflected a wider state and national trend in the 1970s in which busing was either abandoned, outlawed, or (as with Maple) the burden was placed entirely on the minority community.

“Thus the debate over busing in the late 1970s was primarily a debate over whether white students could be compelled to participate in desegregation programs, or whether that burden would fall exclusively on nonwhite students,” Hosang writes.

In his book Why Busing Failed, historian Matthew Delmont discusses how the busing debate was often framed in ways that downplayed the civil rights/constitutionality of the issue.

“White parents and politicians framed their resistance to school desegregation in terms of ‘busing’ and ‘neighborhood schools.’ This rhetorical shift allowed them to support white schools and white neighborhoods without using explicitly racist language,” Delmont writes.

Ultimately, Prop 1 passed by a large majority. Like Prop 21, it was challenged on legal grounds as unconstitutional. Unlike Prop 21, it held up to legal challenge. Its appeal made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1982, where the court voted 8-1 to uphold its constitutionality.

The lone dissenting vote was Justice Thurgood Marshall, who wrote in his dissent, “The fact that California attempts to cloak its discrimination in the mantle of the 14th Amendment does not alter this result.”

“The Supreme Court ruling was a death knell for mandatory desegregation programs throughout the state,” Hosang writes. “The end of mandatory desegregation meant that the burden of busing had fallen almost exclusively on students of color.”

For example, “by 1980, Black students in California would be more likely to attend a segregated school than in any state in the South except Mississippi,” Hosang writes.

These continuing patterns of segregation, now given legal support, continue to today.

“Twenty-five years after the passage of the Robbins Amendment, patterns of racial isolation and segregation were at all-time highs,” Hosang writes.

Fighting for the Maple Community Center

After its closure in 1972, Maple Elementary School became the Maple Community Center (MCC), housing a preschool, Headstart, a daycare, and an experimental Community Open School.

Every five years or so, the Maple area residents had to fight to keep even these programs. In 1978, the Fullerton School District first considered closing the MCC, but ultimately decided against it.

In 1983, the District again proposed closing the MCC, citing a budget deficit. The Board of Trustees initially considered closing either Orangethorpe, Commonwealth, or Hermosa Drive Schools, but shied away from closing any of these after outcry from parents.

“Whenever financial problems come up, they [trustees] talk about closing Maple—we’re always picked on,” Martha Rodriguez (a Maple parent) told the Fullerton News-Tribune.

Faced with the possible closure of the MCC, parents and advocates attended FSD Board meetings in great numbers in February and March of 1983. They also organized a letter-writing campaign to board members and the district.

One particularly eloquent letter was submitted by Brig Owens, an African American NFL player who grew up in the Maple neighborhood.

In his letter to then District Superintendent Duncan Johnson, Owens called the MCC “an extremely necessary facility. This decision not only will affect the children and lives of their families, but it will affect the community as a whole,” Owens wrote. “Too often in the face of progress we lose sight of the true needs of our community and families…I realize tough decisions have to be made and there are no easy answers but let us not sacrifice these programs that are for the betterment of the community.” (Fullerton News Tribune, 1983).

At a Fullerton School District Board meeting in March 1983, around 175 Maple neighborhood residents showed up wearing “Keep Maple Open” buttons.

As reported in the News-Tribune, “Thuc Nguyen, a mother of a child in pre-school at the Center and a full-time volunteer there, broke down in tears at one point in her speech to trustees.”

“How can I explain to my son how Maple won’t be there for him?” Ms. Nguyen said. “I am a single parent of two pre-school children. I don’t think my children can handle another breakup.”

As a result of the parents’ organizing, the Board did not close the MCC in 1983.

The Maple Alumni Committee

In 1983, Bobby Melendez, Vivien “Kitty’ Jaramillo and others from the Maple neighborhood decided to organize an annual get-together for families in the neighborhood whose kids had been or were being bused to schools outside the neighborhood.

This group eventually became the Maple Alumni Committee.

“We started in 1983 to get together for picnics, just to keep ourselves together, so our children could know each other, so we could just bond one time a year,” Melendez said in an interview with The Observer.

One consequence of closing Maple School was to cut off the normal inter-familial ties that come with having a school in your neighborhood.

“The school would have served that function but as we were all in the waning years of having gone to Maple School, having the experience of being bused out together, I think that kind of galvanized our relationship together—having that similar experience,” Melendez said. “So that alumni committee organized dances, and the dances became fundraisers for Maple School.”

By the late 1980s, the prospect of re-opening Maple as an elementary school would become the subject of much discussion and debate.

‘White Flight’

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s the percentage of ethnic minority students (mainly Latino and Asian) in the Fullerton School District rose steadily, mirroring statewide and national trends.

“1982 minority student enrollment was 38%, up 4% from last year and more than three times what it was 15 years ago,” states a 1984 article in the Fullerton Observer.

This steady influx of Latinos and Asians created a few key challenges for the district: the need for more bilingual education, exacerbation of de facto segregation, and white backlash.

A 1987 Fullerton Observer article entitled “Concerned Parent Charges ‘White Flight’ at Richman” quotes a parent of a student at Richman elementary saying, “One of my son’s friends told him that the reason he was transferring out of Richman was ‘there were too many Mexicans there.’”

The article describes how some white parents were removing their children from Richman, a south Fullerton school with a high Latino enrollment, complaining about bilingual classes and a perceived lowering of educational quality.

“Expectations seem to be lower,” said one parent, who chose to have her two children transferred out of Richman. “My two boys were beginning to feel bad about themselves and showing prejudice, which I don’t like; so we decided to take them out. We have to take care of our own.”

By 1988, Richman was the new Maple, with a nearly 80% minority population. Also in 1988 the first ever Latina was elected to the FSD Board of Trustees, Anita Varela.

Re-Opening Maple Elementary?

In 1988, an ad hoc District Advisory Committee was formed to study these changing demographic trends, as well as overcrowding in some schools. The committee ultimately recommended reopening Maple as an elementary school. The merits of this recommendation were debated in a series of community meetings.

“I think (re-opening Maple) is probably going to be one of the greatest days for our community,” Bobby Melendez said. “I think it’s going to have a positive effect on our community because it’s a rallying point of the community, the focal point of the community.”

Trustee Fred Mason and others, while not opposed to re-opening Maple, expressed concern that doing so could re-create a segregated school, due to neighborhood demographics.

“We’ll be segregated again; we haven’t learned anything in 20 years,”

Maple resident Gil Perkins said.

The chair of the committee, Ellen Ballard, said that the priority of the committee was quality education and language instruction rather than correcting “ethnic imbalance.”

Trustee Anita Varela, while not opposed to re-opening Maple, pointed out that “the District had not been serving the interests of Limited English Proficiency (LEP) students throughout the city in its existing programs, and wasn’t prepared for the challenge of a linguistically-segregated school.”

“I would like to see Maple reopened with bilingual teachers and a bilingual principal,” Maple area parent Terry Garcia said. “But first the school would have to be fixed up and the neighborhood parents involved in the reopening before, during, and after.”

A Magnet School?

In 1989, the Fullerton City Council appointed another “Task Force” committee to study and make recommendations about re-opening Maple. During these meetings, one point of discussion was (again) whether re-opening Maple would re-create a segregated school.

One recommendation was to re-open Maple as a “magnet” school—to create such unique and strong educational programs that students from around the City would be drawn to Maple.

Ultimately, this second committee also recommended re-opening Maple as an elementary school. When the committee presented its recommendations in a series of community meetings in 1990, the same debate about whether re-opening Maple would re-create a segregated school continued.

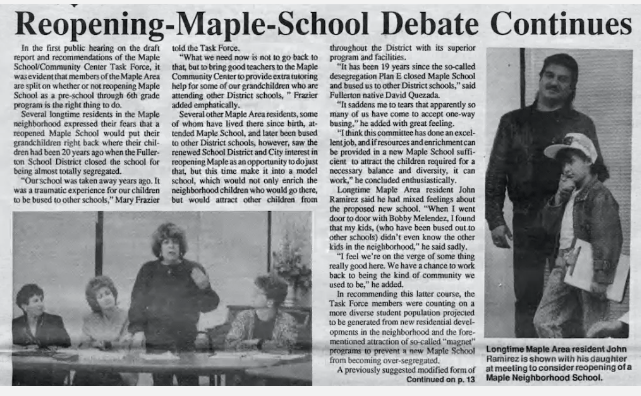

A March 1990 article in the Fullerton Observer states, “Several longtime residents in the Maple neighborhood expressed their fears that a re-opened Maple School would put their grandchildren right back where their children had been 20 years ago when the

Fullerton School District closed the school for being almost totally segregated.”

Those in favor of re-opening Maple expressed hope in the possibility of a “magnet” school that would draw diverse students and achieve integration.

“I think this committee has done an excellent job, and if resources and enrichment can be provided in a new Maple school sufficient to attract the children required for a necessary balance and diversity, it can work,” said David Quezada.

An editorial published in the June 1990 issue of the Fullerton Observer expressed doubts about the feasibility of this option: “We are not aware of any examples where magnet schools located in minority neighborhoods have been successful in drawing enough Anglo students to achieve an integrated student body.”

Unfortunately, this editorial would prove prophetic. In 2020, 24 years after Maple was re-opened in 1996, the demographics were virtually identical to 1972, when the school was closed.

But in 1990, a cautious optimism prevailed. The Fullerton School Board accepted the recommendations of both committees and hired a consultant to develop a plan to re-open Maple Elementary School.

It would be six more years before the first kindergarten classes began at Maple.

To be continued…

Leave a comment