The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

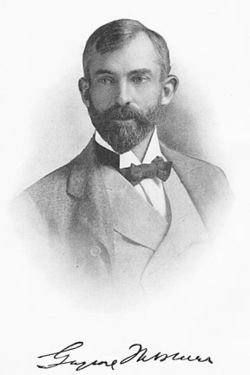

I’ve recently been reading Kevin Starr’s excellent book Inventing the Dream: California Through the Progressive Era (the second in an epic seven-volume history of California), and came across a section on a colorful character named Henry Gaylord Wilshire, who was one of the initial developers of Fullerton. He partnered with the Amerige brothers to establish the town, and Wilshire Ave. is named after him. Although he owned an orange ranch here, Wilshire did not confine his activities to Fullerton. He made his millions in real estate and other Southern California business ventures; however, he was mainly known for being one of the most outspoken Socialists of his era. Though in the minority politically, he was not alone in his political views.

“Turn-of-the-century California sustained an active Socialist minority whose disgust with the excess and corruption of the corporate hold on California politics fed directly into the Progressive reforms,” Starr writes.

It was Socialists like Wilshire who “helped make non-threatening, even respectable, such notions as the public ownership of utilities, prison and hospital reform, social welfare, public housing, workmen’s compensation, and other social programs eventually enacted by the Progressives.”

The publication of Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel Looking Backward: 2000-1887 inspired the formation of [socialist] Nationalist Clubs throughout the United States. The California Nationalist Club formed in Los Angeles in 1889. By 1900, there were 62 local Nationalist Clubs in California alone.

“Composed mainly of middle-class intellectuals,” Starr writes, “the Nationalist movement, so the Overland Monthly reported in June 1890, ‘put a silk hat on socialism’ by making socialist ideas acceptable to ‘people connected with literature and the professions.’”

H. Gaylord Wilshire, president of the Fullerton and Anaheim Nationalist clubs, ran for congress as a Socialist in both 1890 and 1900.

“In his [Wilshire’s] eccentricities and solid accomplishments, his paradoxical entrepreneurism, his flirtation with quackery and his sound, even prophetic, notions of social reform,” Starr writes, “no Socialist Californian could have better exemplified the paradoxes of Socialism, Southern Californian style, than this young Fullerton rancher-entrepreneur.”

Wilshire was born in 1861 in Cincinnati to a wealthy banker. He dropped out of Harvard and after failing in a business venture moved to California where “he pursued two seemingly contradictory ambitions–success and socialism (to which he converted in 1887),” according to Starr.

He and his brother made a lot of money in the Southern California land boom of the 1880s.

“The brothers Wilshire, helped along by some family money, speculated in Los Angeles, Santa Monica, Pasadena, Long Beach (they bought up the shorefront), and Orange County real estate, making money in each instance,” Starr writes. “Settling on a ranch near the city of Fullerton, where he helped to develop, Wilshire had transformed himself by 1890, the year the Nationalists nominated him for Congress, into a wealthy rancher-entrepreneur, growing walnuts and citrus on his property and pioneering the introduction of the grapefruit.”

Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles is named for the brothers Wilshire.

“H. Gaylord Wilshire (as he signed himself) was a promoter and a visionary in the style of Abbot Kinney of Venice and a number of other Southern California eccentrics of this era: a visionary, and perhaps something of a quack, the Wizard of Oz behind the green curtain,” Starr writes. “Wilshire’s promotion of Socialism occurred on the same flamboyant level as his sale of stock or his pioneering billboard advertising in Los Angeles in the early 1900s.”

After losing the congressional election in 1890, he moved briefly to New York (where he ran and lost an election for state attorney general) and then to London, where he met and befriended his hero George Bernard Shaw.

He returned to Los Angeles in the late 1890s, and ran once again for Congress in 1900, again as a Socialist, and got four thousand votes, “the largest single vote thus cast for a Socialist candidate in the United States—but still not enough to get him into Congress.”

Ultimately, it was not as an elected official that Wilshire would leave his mark, but rather as a journalist and publisher.

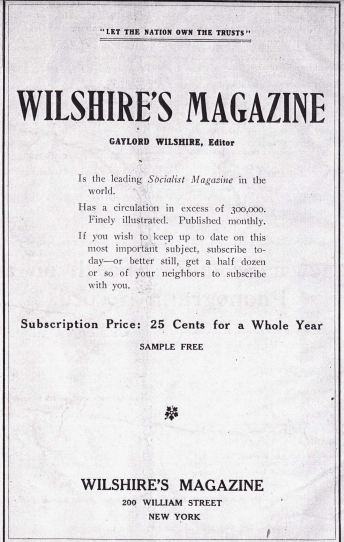

He founded the Weekly Nationalist magazine in Los Angeles in 1889 before launching the socialist magazine the Challenge (a title he later changed to Wilshire’s Magazine).

The Challenge was eventually banned from the United States mail for being subversive. To get around the ban, Wilshire moved the magazine to Toronto, from which, by international agreement, it could be mailed into the United States.

“Wilshire built the circulation of Wilshire’s Magazine to an impressive 425,000 copies per issue,” Starr writes. “During the Progressive Era, Wilshire’s Magazine was the most influential Socialist journal in the United States, and its subsidiary publishing house, the Wilshire Book Company (which also sponsored a Socialist Book Club), introduced a wide variety of Socialist authors, European and American, to American audiences.”

Wilshire personally wrote quite a bit of Wilshire’s Magazine in essays in which he “scolded capitalism and the trusts roundly and argued for the socialist alternative.”

Wilshire advocated a type of Fabian socialism (inspired by his friend George Bernard Shaw) which was nonviolent, nonrevolutionary, and non-Marxist.

“From the vantage point of today, a half century after the New Deal, it is difficult to understand why Wilshire’s Magazine was ever considered dangerous enough to be banished from the mails,” Starr writes. “Rejecting a Marxist theory of revolution and class struggle, the Fabians believed that modern industrial societies, unless repressed, would naturally evolve into more cooperative, socialized economic structures. As a writer and platform performer, Wilshire argued for the nationalization of railroads and utilities, the municipal ownership of water, gas, electricity, telephones, and streetcar service, women’s suffrage, public reclamation projects to put the unemployed to work, an eight-hour day, an end to child labor, free public schools (to include hot lunches and textbooks), unemployment insurance, a social security system, a national public highway trust—and other, similar ideas, few of them (with the exception of the nationalization of heavy industry) outside the mainstream of liberal social thought through Progressivism and the New Deal.”

Other notable California socialists of this time period included poet Edwin Markham and novelist Jack London. Markham wrote a famous socialist poem entitled “the Man With the Hoe” and London published a socialist novel, The Iron Heel.

“Wilshire’s broadly conceived, humanistic Socialism—nonviolent, nonrevolutinary, interdenominationally assimilative, nurtured on Fabianism and edging into Social Democracy—was typical of much of the upper-middle-class Socialism of Southern California,” Starr writes. “This sensibility, in turn, nurtured a species of pre-Progressivism at the turn of the century.”

A book about Wilshire’s life was published in 2012 entitled Henry Gaylord Wilshire: the Millionaire Socialist by Lou Rosen.

Leave a comment