The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

“From 1882, when the first Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, until about 1930, the history of farm labor in California has revolved around the cleverly manipulated exploitation, by the large growers, of a number of suppressed racial minority groups which were imported to work in the fields.”

–Carey McWilliams, Factories in the Field: The Story of Migratory Farm Labor in California

I’ve recently been featuring a series of portraits of early American settlers in Fullerton, many of whom made their wealth from agriculture–largely citrus and walnuts. The basis of these portraits is Samuel Armor’s massive History of Orange County. However, one problem with this book is that the biographies of local “pioneers” it contains were actually paid for by those being written about or their families. Therefore, there is nothing negative in these bios.

For example, one element that is little discussed in these portraits is who did the actual labor on these farms. Granted, some of the farms were small enough that perhaps the owners did the work. However, the larger farms often relied on immigrant labor.

In 1939, the same year The Grapes of Wrath was published, shattering myths of paradise in California, a non-fiction book was published called Factories in the Field: The Story of Migratory Farm Labor in California, written by a young lawyer/journalist named Carey McWilliams. McWilliams’ book is a carefully researched work of social history.

For today, I’d like to focus on just the section of the book that deals with Chinese immigrant labor.

Between the decades of 1870 and 1890, fruit gradually replaced wheat as the main crop of California. Reasons for this included changes in market conditions, droughts, and high freight rates. While wheat could be harvested mechanically and required less labor, fruit often had to be hand-harvested and required a large labor force.

Enter the Chinese laborer.

The completion of the trans-continental railroad in 1869, which had relied heavily on Chinese labor, created a lot of job-seeking Chinese immigrants. These immigrants were a Godsend for large fruit growers in California, as Chinese laborers would work for very low wages.

According to the California Bureau of Labor, Chinese workers constituted around 80 percent of the agricultural laborers in the state in 1886. Low-paid Chinese labor was a major factor in the early economic success of the California fruit industry.

Large fruit growers faced a problem, however…large-scale and vicious racism against Chinese people in late 19th century America. As early as 1854, a California Supreme Court decision had included Chinese in “a statute which prohibited the testimony of Negroes, mulattos, and Indians, in cases to which white men were parties.” According to Carey McWilliams, “Newspapers had stated as early as 1850 that the Chinese were being murdered with impunity.”

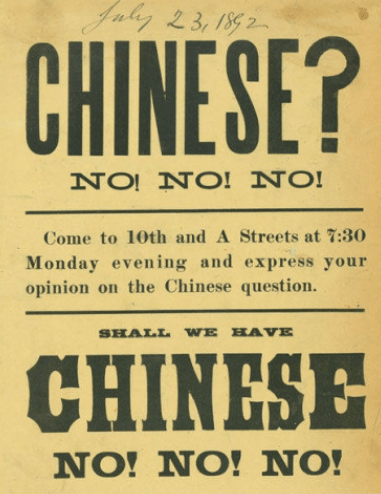

Anti-Chinese clubs sprang up around California starting in the 1860s. Cities like San Francisco passed discriminatory ordinances making it illegal to carry baskets on the sidewalks or for men to grow their hair a certain length. Chinese people were routinely harassed and expelled from their homes and places of work.

This anti-Chinese sentiment became federal law in 1882 with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which curtailed Chinese immigration to America and made official what was already widely practiced. Chinese were forbidden from becoming U.S. citizens.

The Geary Act of 1892 continued the provisions of the Chinese Exclusion Act and also provided for massive deportation of Chinese from the US. The language of the Geary Act is eerily familiar. It “forced the burden of proving legal residence upon the Chinese, and required that all Chinese laborers register under the act within one year of its passage.”

When these legal measures failed to expel Chinese people as swiftly as people wanted, Californians resorted to vigilante “justice,” as shown by the following examples, as excerpted from McWilliams’ book:

“On August 15 (1893), riots broke out near Fresno: Chinese were driven from the fields and were ‘compelled to make lively runs for Chinatown.’ Chinese labor camps were raided and fired.”

“In Napa Valley, on August 17, a white laborers’ union was formed, and a mass meeting protested the further employment of the Chinese in the prune orchards.”

“In Southern California, at Compton, the Chinese were barricaded in packing sheds where they were forced to sleep for safety, while ‘hoodlums’ raided the fields and drove out the Chinese.”

“On September 3 anti-Chinese raiders swooped down on Redlands’ Chinatown, broke into houses, set afire to several buildings, looted the tills of Chinese merchants, and generally terrorized the Chinese.”

“At Tulare, Visalia, and Fresno, hundreds of white men were busy ‘routing out the Chinese, terrifying them with blows and pistol shots, and driving then to the railroad station and loading them on the train.”

During the years when this anti-Chinese activity was most acute (1893-1894), the United States was in the throes of a major economic depression. During this economic turmoil, Americans sought a scapegoat for their troubles, and found that scapegoat in Chinese workers.

Here in Fullerton, Chinese workers had been a presence since the beginning of the town. Bob Ziebell writes in Fullerton: A Pictorial History, “George Amerige says he installed the town’s first water system ‘employing Chinamen to do the excavation work on the ditches.’”

The Fullerton Tribune newspaper featured a running trend of articles dealing with the topic of Chinese Exclusion, all of which heartily supported it.

On October 7, 1893, Tribune editor Edgar Johnson reported that “Two Chinamen were arrested at Santa Ana Tuesday and taken to Los Angeles to go before Judge Ross on a charge of violating the Geary act by not registering within the time prescribed by law.” On Jan 6 of 1894, Johnson called it a “well-known fact that the Chinese do not make desirable residents in this country.” Edgar Johnson often refers to Chinese people with the racist (but commonly used) term “Chinamen.”

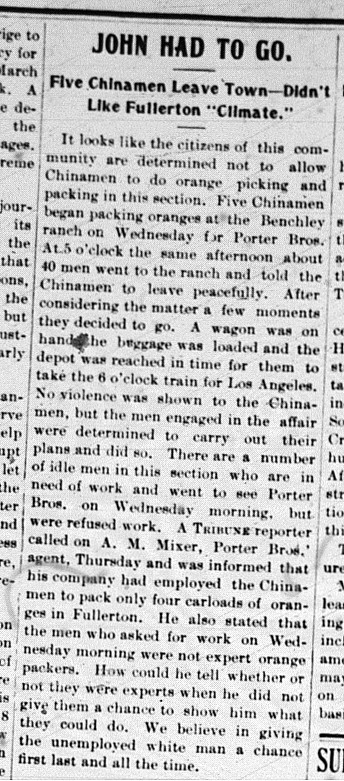

On February 17, 1894, Johnson reported an event that happened in Fullerton. Apparently a mob of 40 locals forced some Chinese workers to leave town. Here’s a screen shot of this article and its opening paragraph:

In a CSUF Master’s Thesis entitled “Citrus Culture: The Mentality of the Orange Rancher in Progressive Era North Orange County,” Laura Gray Turner describes conditions for Chinese laborers in the orange groves, which were not ideal. Turner writes, “Six days a week they labored, often sleeping under the trees in the groves…in crude bunkhouses or small shanties…wages were probably about a dollar per day.” Chinese, like other minority groups, were forced to live apart from the dominant/white community. According to Turner, newspaper accounts of the Chinese presence in Orange County “reveal a certain ‘we-they’ mentality and a sense of social superiority exhibited by the white grower elite.”

With increasing anti-Chinese sentiment, Chinese labor was eventually replaced by Japanese labor, which was then replaced by Mexican labor. More on how these immigrant groups were marginalized next time.

Leave a comment