The following is from a work-in-progress about the history of Fullerton. You can support my ongoing research and writing on Patreon.

In fourth grade I, like every other kid who attends public school in California, had to build a model of a mission. The state-sponsored curriculum taught me that these were sites where kindly Spanish padres and California Indians lived together peacefully and happily.

This was also the impression I got when, as an adult, I visited Mission San Juan Capistrano. There, a nice lady dressed as an “old Californian” told pretty much the same story.

In school, I was also taught that no one knows what happened to the native Californians of Southern California. They, like the wooly mammoths who used to roam these lands, were gone, extinct.

Imagine my surprise, then, when a few years ago, I happened to meet actual, living members of the local tribe (which has historically been called the Gabrieleno, but they prefer the name Kizh). I met the chief (Ernie Salas) and others at a special event at the little paleontology museum at Ralph Clark Park in Fullerton. Speaking to these native Californians, I learned a completely different version of the California mission story.

They described the missions as sites of slavery, disease, brutality, and death. The missions, according to the local natives, were places of horror and trauma.

After meeting and befriending these living native Californians, I became fascinated with this other side of the California mission story. Based upon my research, I made some startling discoveries. While there are plenty of books written about the missions, they seem to be pretty well divided into two categories: “nostalgic” books (which perpetuate the “happy” mission story), and academic books (which tell a darker and more complex story).

At present, there seem to be more books available to the general public of the nostalgic type than the academic type.

Thankfully, this appears to be changing. Quite recently, a new batch of scholarship (and even popular histories) have come out which dive deeply into California history from the native point of view.

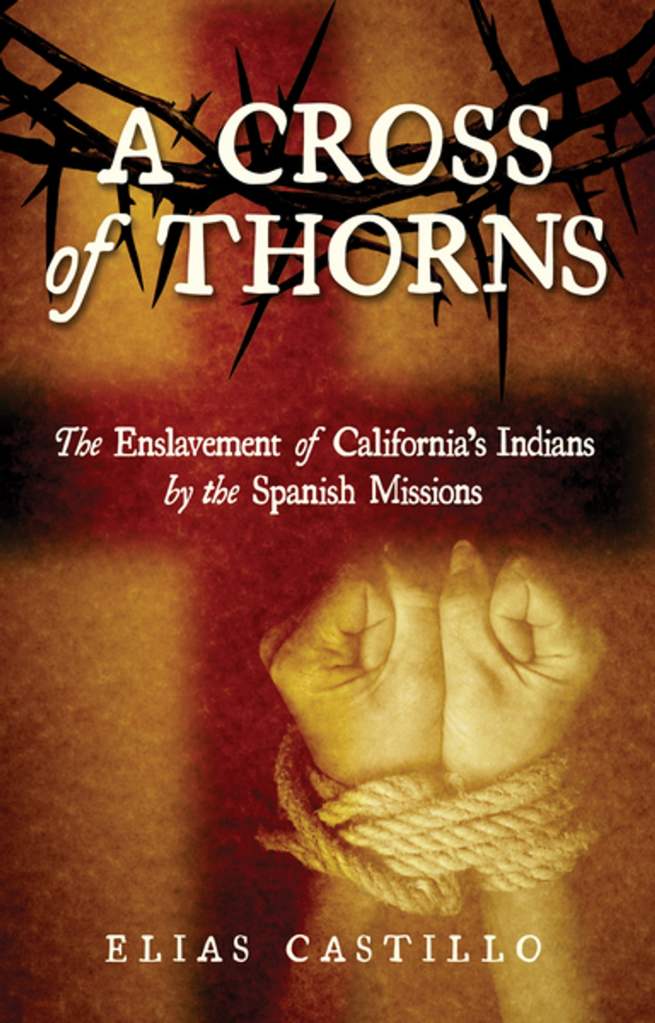

Such a book is Elias Castillo’s A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions, which came out in 2015.

His book, based upon a bedrock of research and primary sources, strives to shine a light on the real story of the missions, and the tragedy they wrought upon the native peoples of California.

In the interest of sharing knowledge and ideas, and to hopefully correct some widespread historical misconceptions, I have decided to present some of the historical evidence Castillo provides.

Some may ask: “Why does this matter? The past is the past. Get over it.” To that, I would respond that it matters very much to living descendants of those who were killed, enslaved, and mistreated. Understanding their stories helps us to better grapple with ourselves as a State and as a society.

It’s also important for people to better understand this because many California tribes (like the Kizh) are still striving for official federal recognition, which will afford them certain benefits and a proper place in our historical understanding.

To that end, I here present some documentary evidence for the tragedy that was the California mission system. These are all primary sources, with a bit of context given for each.

Whipping and Death as “Spiritual Benefit”

On July 31st, 1775, Father Junipero Serra sent a letter to Spanish military commander Fernando Rivera y Moncada, requesting that four Indians who had tried to flee from Mission Carmel be whipped. He also offered to send shackles, in case the commander didn’t have any:

“Two or three whippings which your Lordship may order applied to them on different days may serve, for them and for the rest, for a warning, may be of spiritual benefit to all; and this last is the prime motive of our work. If your Lordship does not have shackles, with your permission they may be sent from here. I think that the punishment should last one month.”

On January 7th, 1780, Serra wrote a letter to then-governor of California Felipe de Neve, defending his practice of whipping the natives:

“That the spiritual fathers [friars] should punish their sons, the Indians, by blows appears to be as old as the conquest of these kingdoms.”

Governor Felipe de Neve envisioned a secular future for the missions, where the Indians would be freed and granted basic human rights. He wrote that the Indians fate was “worse than that of slaves.”

Due to mistreatment, confinement, and widespread diseases for which the natives had no immunity, the mission Indians began to die in huge numbers. Rather than mourn them, however, Serra was happy to see so many newly-baptized souls go to heaven. In a report dated July 24, 1775 to Friar Francisco Pangua, his superior, Serra wrote:

“In the midst of our little troubles, the spiritual side of the missions is developing most happily. In [Mission] San Antonio [de Padua, about 60 miles south of Mission Carmel] there are simultaneously two harvests, at one time, one for wheat, and of a plague among the children, who are dying.”

“A Species of Monkey”

The Franciscan padres generally considered themselves to be culturally, intellectually, and spiritually superior to the native peoples, which tended to provide a justification for mistreatment. Friar Geromino Boscana (stationed at Mission San Juan Capistrano) writes:

“The Indians of California may be compared to a species of monkey; for in naught do they express interest, except in imitating the actions of others, and, particularly in copying the ways of the razon [men of reason] or white men.”

Father Serra’s successor, Friar Fermin, also considered the Indians to be akin to “lower animals.” In 1786, Fermin wrote:

“They satiate themselves today and give little thought to tomorrow…a people without education, without government, religion or respect for authority, and they shamelessly pursue without restraint whatever their brutal appetites suggest to them.”

An Enlightened Point of View

Sometimes, travelers and explorers visited the missions, and their writings provide a unique, first-hand account of the actual conditions. Such was the case with French Navy Captain Jean-Francois de Galaup, Comte de Laperouse, who was the leader of a major scientific expedition. His ships sailed into Monterey Bay on September 14, 1786, and Laperouse describes his shock at seeing the conditions under which the Indians were forced to live. He compares the mission to slave plantations he’d seen in the Caribbean:

“Everything…brought to our recollection a plantation at Santo Domingo or any other West Indian island…We observed with concern that the resemblance is so perfect that we have seen both men and women in irons, and others in stocks. Lastly, the noise of the whip might have struck our ears.”

Laperouse continues, “Women are never whipped in public, but in an enclosed and somewhat distant place that their cries might not excite too lively a compassion, which might cause the men to revolt.”

The men were whipped “exposed to the view of all of their fellow citizens, that their punishment might serve as an example.”

It’s interesting to contrast the worldviews of a French explorer like Laperouse, imbued with the spirit of the Enlightenment and the rights of man, with a Spanish missionary like Serra, still imbued with the ideas of the Middle Ages. Serra was actually a part of the infamous Spanish Inquisition. Laperouse laments the ideas and methods of the Spanish missionaries, writing, “I could wish that the minds of the austere charitable, and religious individuals I have met with in these missions were a little more tinctured with the spirit of philosophy.”

Laperouse and other writers of the time show that violence and brutality toward native peoples wasn’t “just the way things were” or “just how everyone thought back then.” There were people living at the time who believed in the notion of human rights

De Facto Slavery

Writings from the time demonstrate that the California Missions were basically west cost slavery.

Laperouse writes: “The moment an Indian is baptized, the effect is the same as if he had pronounced a vow for life. If he escape to reside with his relations in the independent villages, he is summoned three times to return; if he refuses, the Missionaries apply to the governor, who sends soldiers to seize him in the midst of his family and conduct him to the mission, where he is condemned to receive a certain number of lashes with the whip.”

Overseers called alcaldes were also tasked with capturing, returning, and punishing runaways. Indians were not allowed to leave mission grounds without permission.

American Sherbourne F. Cook, who visited the missions, described women being locked up at night in unsanitary, cramped quarters: “There can be no doubt that the women were packed in tightly, and that the accumulation of filth was unavoidable…it is unbelievable that they (Indians) should not have resented years of being confined and locked in every night in a manner which was so alien to their tradition and nature.”

Cruel and Unusual Punishments

American farmer Hugo Reid, who was sympathetic to the Indians, describes the strange barbarism of a Friar Jose Maria Zalvidea at Mission San Gabriel:

“He was not only severe, but he was, in his chastisements, most cruel. So as not to make a revolting picture, I shall bury acts of barbarity known to me through good authority, by merely saying that he must assuredly have considered whipping as meat and drink to them, for they had it morning, noon, and night.”

Friar Ramon Olbes of Mission Santa Cruz, in an incident recounted by former neophyte (baptized Indian) Lorenzo Asisara, attempted to force a childless Indian couple to have sex in his presence to prove that they had potential to conceive [probably because Indians were dying at alarming rates]. The husband “refused, but they forced him to show them his penis in order to show that he had it in good order.”

Olbes sent the husband to a guard house in shackles. He made the wife enter another room in order to examine her private parts. She resisted him and there was a struggle between the two. Olbes ordered the guards to give her fifty lashes and lock her in the nunnery. He then ordered that a wooden doll be made like a newborn child, and ordered her to present herself in front of the church for nine days. Olbes had the husband shackled and made him wear cattle horns affixed with leather.

Taking Mass at Gunpoint

Ludovik Choris, an artist traveling with a Russian expedition, visited Mission San Francisco in 1816, and described how attendance at church services was compulsory: “All the Indians of both sexes without regard to age, are obliged to go to church and worship…Armed soldiers are stationed at each corner of the church.”

Captain Frederick William Beachey of England’s Royal Navy visited Mission San Jose in 1826, and described how Indians there were rounded up and forced to go to church twice a day:

“Morning and evening Mass are daily performed in the Missions…at which all the converted Indians are obliged to attend…After the bell had done tolling, several [Indian overseers] went round to the huts, to see if all the Indians were at church, and if they found any loitering within them, they exercised with tolerable freedom a long lash with a broad thong at the end of it; a discipline which appeared the more tyrannical as the church was not sufficiently capacious for all the attendants and several sat upon the steps.”

Thus, Indians who chose not to attend church were whipped. Beachley continues, describing a similarly grisly scene inside the church:

“The congregation was arranged on both sides of the building, separated by a wide aisle passing along the centre, in which were stationed several [overseers] with whips, canes, and goads, to preserve silence and maintain order, and…to keep the congregation in the kneeling posture. The goads were better adapted to this purpose than the whips, as they would reach a long way, and inflict a sharp puncture without making any noise. The end of the church was occupied by a guard of soldiers under arms, with fixed bayonets.”

Church services were given in Latin (which the Indians could not understand), and (against the goal of educating them), the official mission policy was, as with slaves, not to teach the Indians to read or write.

In a letter written in 1769 to Father Serra’s close friend Friar Francisco Palou, Spanish Visitor-General Jose de Galvez writes, “I stress my request to your most reverend person that you do not teach the Indians how to write; for I have enough experiences that such major instruction perverts and hastens their ruination.”

Followers of St. Francis Living Like Kings

The friars who founded the California missions were of the Franciscan order, which was founded by St. Francis of Asisi, the famous saint who took a vow of poverty. Like their founder, Franciscans were obliged to take a vow of poverty. However, accounts exist of Franciscans living luxuriously in the missions, while the Indians did not share in the great wealth the vast mission lands amassed.

Pablo Tac, a Luiseno Indian who grew up at Mission San Luis Rey, wrote an account of his experiences and described how the “Father is like a king. He has his pages, alcaldes, majordomos, musicians, soldiers, gardens, ranchos, livestock, horses by he thousands, cows, bulls by the thousand, oxen, mules, asses, twelve thousand lambs, two hundred goats, etc.”

In addition to being religious institutions, the missions also grew to be large commercial enterprises, with hundreds of thousands of acres for crops and livestock, where the fathers amassed great wealth, and often traded with the English and Americans.

Meanwhile, according to Indian Lorenzo Asisara, the friars “were very cruel toward the Indians. They abused them very much. They had bad food, bad clothing. And they made them work like slaves. I was also subject to that cruel life. The Fathers did not practice what they preached.”

Death and Despair

Due to mistreatment, disease, and deplorable conditions, nearly half of the missions’ populations died each year. From 1779 to 1833, the year the missions were effectively dissolved, there were 29,100 births and a staggering 62,600 deaths.

Russian explorer Otto von Kotzebue, who visited mission San Francisco in 1816, wrote that “the uncleanliness in these barracks baffles description, and this is perhaps the cause of great mortality: for of 1,000 Indians at St. Francisco, 300 die every year.”

Because of all this death, combined with the tragedy of being cut off from their culture and traditions, depression and despair took its toll on the mission Indians, as evidenced by accounts from visitors.

British Navy Captain George Vancouver visited Mission San Francisco while exploring the California coast in 1792, and described the demeanor of the Indians: “All the operations and functions both of body and mind appeared to be carried out with a mechanical, lifeless, careless indifference.”

The Russian artist Choris wrote that he never saw an Indian laugh: “They look as though they were interested in nothing.”

Spanish Accounts of Abuses

Some may argue that these outsiders descriptions were motivated by opposition to Catholicism or Spain, but there are ample records in the mission archives themselves which corroborate the picture.

Friar Antonio de la Concepcion Horra, assigned to lead Mission San Miguel in 1798, wrote a letter to the Viceroy of Mexico expressing his dismay at mission life:

“Your Excellency, I would like to inform you of the many abuses the are commonplace in that country. The manner in which the Indians are treated is by far more cruel than anything I have ever read about. For any reason, however insignificant it may be, they are severely and cruelly whipped, placed in shackles, or put in stocks for days one end without receiving even a drop of water.”

The governor of California, Diego de Borica looked into Horra’s complaints and wrote: “Generally, the treatment given the Indians is very harsh. At San Francisco, it even reached the point of cruelty…I also know why they have fled. It is due to the terrible suffering they experienced from punishments and work.”

Fleeing For Their Lives

Due to the misery of mission life, Indians sometimes attempted to escape. For example, between 1769 and 1817, there were 473 documented cases of Indian fugitives from Mission San Gabriel alone.

A group of Saclan and Huichin Indians who had fled Mission San Francisco in 1797 were asked by Spanish officials why they had run away. Here are some of their answers, dutifully recorded by Lieutenant Jose Arguello:

Tiburcio: He testified that after his wife and daughter died, on five separate occasions Father Danti ordered him whipped because he was crying. For these reasons he fled.

Magin: He testified that he left due to his hunger and because they had put him in the stocks when he was sick, on orders from the alcalde.

Malquiedes: He declared that he had no more reason for fleeing that that he went to visit his mother, who was on the other shore.

Liborato: He testified that he left because his mother, two brothers, and three nephews died, all of hunger. So that he would not also die of hunger, he fled.

Timoteo: He declares that the alcalde Luis came to get him while he was feeling ill and whipped him. After that, Father Antonio hit him with a heavy cane. For those reasons, he fled.

Magno: He declared the he had run away because, his son being sick, he took care of him and was therefore unable to go out to work. As a result, he was given no ration and his son died of hunger.

Prospero: He declared that he had gone one night to the lagoon to hunt for ducks for food. For this Father Antonio Danti ordered him stretched out and beaten. Then, the following week he was whipped again for having gone out on paseo (to visit his village). For these reasons he fled.

Russian hunter Vassili Petrovitch Tarakanoff, who was taken prisoner by the Spanish in 1815, recalls witnessing the treatment of Indians who had fled their mission and were recaptured:

“They were bound with rawhide ropes, and some were bleeding from wounds, and some children were tied to their mothers…Some of the runaway men were tied on sticks and beaten with straps. One chief was taken out into the open field, and a young calf which had just died was skinned, and the chief was sewn into the skin while it was yet warm. He was kept tied to a stake all day, but he soon died, and they kept his corpse tied up.”

Rebellion

Aside from running away, another reaction to death and mistreatment at the missions was armed revolt.

Diegueno Indians rebelled and burned down Mission San Diego in 1775. When asked why they had burned the mission, the Indians later said “they wanted to kill the fathers and soldiers in order to live as they did before.”

A female Gabrieleno (Kizh) shaman named Toypurina planned a revolt at Mission San Gabriel in 1785. Unfortunately, the plot was discovered and stopped. At her trial in 1786, Toypurina (who is a hero to the Gabrieleno today, sort of like Joan of Arc), said to her accusers: “I hate the padres and all of you for living here on my native soil, for trespassing upon the land of my forefathers and and despoiling our tribal domains.”

Perhaps the most successful uprising involved Quechan Indians who wiped out a mission and two settlements founded by the Spaniards on the California side of the Colorado River in 1781.

There was also the Great Chumash Uprising of 1824, which involved Indians from three Missions (Santa Ines, Santa Barbara, and La Purisima) taking arms against their Spanish oppressors.

After the Missions

In 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain. Missions were secularized in the 1830s. The vast lands were supposed to be re-distributed among the Indians, but things didn’t work out that way. Many were cheated out of property, or lands were seized by corrupt officials. Many Indians became ranch hands on Mexican ranchos. Under Mexican, and then American rule, the Indians would continue to suffer in new and traumatic ways.

Reflecting on the legacy of the missions, Friar Mariano Payeras wrote to his superiors in Mexico City in 1820: “I fear that a few years hence on seeing Alta California deserted and depopulated of Indians within a century of its discovery and conquest by the Spaniards, it will be asked where is the numerous heathendom that used to populate it?…even the most pious and kindly of us will answer: the Missionary priests baptized them, administered the sacraments to them, and buried them.”

Between 1769 and 1890, the Native American population declined from an estimated 300,000 to 16,600.

Whitewashing History

Despite this documented record of oppression, disease, cruelty, and death—the California Missions experienced a revival in the late 19th and early 20th century as a way to market oranges, real estate, and a romantic myth of California’s past.

Castillo writes, “The missions, where thousands of Indians remain buried in unmarked mass graves, were resurrected in the 1890s and early 1900s and rebuilt as monuments to a concocted past that featured a loving, cooperative relationship between the friars and the Indians. Many California leaders, either ignorant of the truth or choosing to ignore what happened, joined in this duplicity.”

In his book Orange County: a Personal History, in a chapter entitled “Our Climate is Faultless: Constructing America’s Perpetual Eden” local writer Gustavo Arellano discusses how American businessmen and early 20th century mass media contributed to the myth of a Spanish Mission past that never existed.

On orange crate label art like Charles Chapman’s Old Mission Brand and in films like Douglas Fairbanks’ The Mark of Zorro (and all the Zorro stories that followed), the mission myth was born—ignoring the ugly historical reality.

This myth continues today. “Across California, streets, playgrounds, and even schools have been named after Padre Junipero Serra,” Castillo writes, “Yet Serra is still revered by many in California as a kindly friar who loved and treated the Indians as if they were his children.”

In Sacramento, on the grounds of the state capitol, there is a bronze statue of Serra. In San Francisco a gigantic statue of Serra overlooks the entrance to Golden Gate Park. And in Washington D.C., in the National Statuary Hall of the nation’s Capitol Building, there is a statue of Serra holding a model of a mission in one hand and a large cross in the other. Not to mention the numerous statues of Serra at the missions themselves.

“For decades, the California State Department of Education has required every elementary school in the state to teach fourth grade pupils of the supposed contributions of not only Junipero Serra, but of the missions themselves,” Castillo writes.

In 1988, Pope John Paul II conferred beatification on Father Junipero Serra, a major step toward becoming a saint.

It seems that, as with American history in general, California still has much reckoning to do with its real past.

Leave a comment